Goose barnacle

Goose barnacles (order Pedunculata), also called stalked barnacles or gooseneck barnacles, are filter-feeding crustaceans that live attached to hard surfaces of rocks and flotsam in the ocean intertidal zone.

| Pedunculata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pollicipes pollicipes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Infraclass: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | Pedunculata |

Biology

Some species of goose barnacles such as Lepas anatifera are pelagic and are most frequently found on tidewrack on oceanic coasts. Unlike most other types of barnacles, intertidal goose barnacles (e.g. Pollicipes pollicipes and Pollicipes polymerus) depend on water motion rather than the movement of their cirri for feeding, and are therefore found only on exposed or moderately exposed coasts.

Spontaneous generation

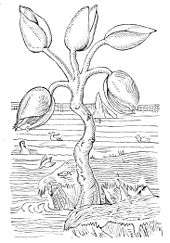

In the days before it was realised that birds migrate, it was thought that barnacle geese, Branta leucopsis, developed from this crustacean, since they were never seen to nest in temperate Europe,[2] hence the English names "goose barnacle", "barnacle goose" and the scientific name Lepas anserifera (Latin: anser, "goose"). The confusion was prompted by the similarities in colour and shape. Because they were often found on driftwood, it was assumed that the barnacles were attached to branches before they fell in the water. The archdeacon of Brecon, Gerald of Wales, made this claim in his Topographia Hiberniae.[3]

Since barnacle geese were thought to be "neither flesh, nor born of flesh", they were allowed to be eaten on days when eating meat was forbidden by Christianity,[2] though it was not universally accepted. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II examined barnacles and noted no evidence of any bird-like embryo in them, and the secretary of Leo of Rozmital wrote a very skeptical account of his reaction to being served the goose at a fast-day dinner in 1456.[4]

Taxonomy

The order Pedunculata is divided into the following suborders and families:[5]

- Heteralepadomorpha Newman, 1987

- Anelasmatidae Gruvel, 1905

- Heteralepadidae Nilsson-Cantell, 1921

- Koleolepadidae Hiro, 1933

- Malacolepadidae Hiro, 1937

- Microlepadidae Zevina, 1980

- Rhizolepadidae Zevina, 1980

- Iblomorpha Newman, 1987

- Iblidae Leach, 1825

- Lepadomorpha Pilsbry, 1916

- Lepadidae Darwin, 1852

- Oxynaspididae Gruvel, 1905

- Eolepadidae

- Poecilasmatidae Annandale, 1909

- Scalpellomorpha Newman, 1987

- Calanticidae Zevina, 1978

- Lithotryidae Gruvel, 1905

- Pollicipedidae Leach, 1817

- Scalpellidae Pilsbry, 1907

As food

In Portugal and Spain, the species Pollicipes pollicipes is a widely consumed and expensive delicacy known as percebes. Percebes are harvested commercially in the Iberian northern coast, mainly in Galicia and Asturias, but also in the Southwestern Portuguese coast (Alentejo) and are also imported from other countries within its range of distribution, particularly from Morocco. A larger but less palatable species (Pollicipes polymerus) was also imported to Spain from Canada until 1999, when the Canadian government ceased exports due to depletion of stocks.

In Spain, percebes are lightly boiled in brine and served whole and hot under a napkin. To eat percebes, the diamond shaped foot is pinched between thumb and finger and the inner tube pulled out of the scaly case. The claw is removed and the remaining flesh is swallowed.[6] Historically, the indigenous peoples of California used to eat the stem after cooking it in hot ashes.[7]

References

- "Pedunculata Lamarck, 1818". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- Michael Allaby (2009). "Barnacles". Animals: from Mythology to Zoology. Infobase Publishing. pp. 75–77. ISBN 978-0-8160-6101-3.

- Beatrice White (1945). "Whale-hunting, the barnacle goose, and the date of the "Ancrene Riwle". Three notes on Old and Middle English". The Modern Language Review. 40 (3): 205–207. JSTOR 3716844.

- Henisch, Bridget Ann, Fast and Feast: Food in Medieval Society. The Pennsylvania State Press, University Park. 1976. ISBN 0-271-01230-7, pp. 48–49.

- Joel W. Martin & George E. Davis (2001). An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. pp. 1–132.

- "Percebes: Grail trail". 23 April 2004 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- The Natural World of the California Indians. By Robert F. Heizer and Albert B. Elsasser.

External links