Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway

The Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway (L&MVLR) was a narrow gauge railway in Staffordshire, England that operated between 1904 and 1934. The line mainly carried milk from dairies in the region, acting as a feeder to the 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge system. It also provided passenger services to the small villages and beauty spots along its route. The line was built to a 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) narrow gauge and to the light rail standards provided by the Light Railways Act 1896 to reduce construction costs.

| Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Abandoned | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | Leek | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1904 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 1934 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 8 1⁄4 mi (13.3 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The route of the line is now a foot- and cycle- path.

Route

The North Staffordshire Railway's branch from Leek ended at Waterhouses (53.0484°N 1.8647°W). The L&MVLR continued from an end-on junction with this line. It ran for 8 1⁄4 miles (13.28 km) down the valley of the River Hamps as far as Beeston Tor, before turning up the limestone gorge that the River Manifold had formed, through to Hulme End (53.1310°N 1.8470°W). The line had a large number of stations in a relatively short distance, and there were refreshment rooms at Thor's Cave and Beeston Tor. In all the line crossed the river Manifold dozens of times - including nine times in the short section between Sparowlee and Beeston Tor.

All stations had rather grand signs (sometimes grander than the facilities) and platforms were just 6 inches (152 mm) high. All stations had sidings except for Beeston Tor and Redhurst Halt.

- Hulme End station was a large building, with adjacent engine and coach sheds (two roads in each). On the timetable it was described as "Hulme End for Hartington". Hartington being some 3 miles (4.8 km) distant.

- Ecton station had both a standard gauge and narrow gauge siding, with a narrow gauge extension to the milk factory. The presence of the railway did not kick-start the local mining industry, as hoped.

- Butterton station (also known locally as Ecton Lea) had a waiting room. There was a siding.

- Wetton Mill station had a station with waiting room, and a standard gauge siding. (It had ceased to be a working mill before the railway was built.)

- At Redhurst Halt an old coach served as a waiting room. There was no siding here.

- Thor's Cave station largely served Wetton village. It had a waiting room. Its refreshment room was moved to Wetton in 1917.

- Grindon station, located at Weags Bridge, had a loop containing a 75 feet (22.86 m) standard gauge siding.

- Beeston Tor station had no siding, but a refreshment room.

- Sparrowlee station served Lee House Farm, but nowhere else, and there was not even a waiting room here. The siding included a 60 feet (18.29 m) standard gauge section.

- At Waterhouses station the platform had booking offices, and there was a goods shed. There were two short loops, and three short sidings which joined with standard gauge lines. (A road-widening scheme in the 1960s has subsequently removed much of the evidence.)

History

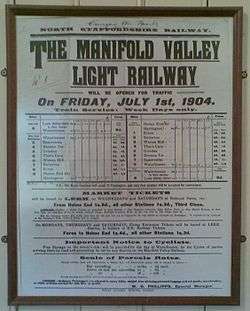

Authorised in 1898, this was the narrow gauge section of the Leek Light Railways. The railway ran for 30 years, from 1904 to 1934. Its engineer was Everard Calthrop, a leading advocate of narrow gauge railways and builder of the Barsi Light Railway in India; the chairman of the company was Charles Bill, MP for Leek.[1] A private concern, it was run by the North Staffordshire Railway on a percentage basis, but it later came under the control of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway in 1923.

The line was constructed to a high standard, Calthrop applying lessons learned on his other railways. Rail used was 35 lb/yard (17.28 kg/m), and the quality of trackwork is reflected in the fact that no re-laying was ever necessary.

The line was a single track, and most services (which began from Hulme End, where the locomotive sheds were) only involved the use of one engine in steam. There was passing loop at Wetton Mill, but it was never used as such.

At Waterhouses the timetable allowed for connections from Leek.

Trains ran at a maximum speed of 15 miles per hour (24.1 km/h), and most halts were run on a request basis. More than this, the train would also often stop to pick up passengers at other places on the lineside footpath, if requested. Timetables mostly show single journey times of 50 minutes (with some showing an hour).

Most outbound freight consisted of milk, in both churns and bulk tankers, and the products of the dairy goods factory at Ecton. In all, some 300 milk churns were handled daily at Waterhouses, and from 1919 a daily milk train ran from Waterhouses to London specifically for this traffic. Latterly milk tanks were used, carried on the transporter wagons. Passenger traffic was minimal – the settlements were mostly some distance from the line – except on Bank Holidays when all the line's rolling stock was used to run frequent services to handle the crowds.

There was some talk of extending the line northwards, whereby Hulme End (and its engine shed) would become the half-way point of the line, but this never materialised.

The railway was filmed in operation for Pathé News in 1930 under the title "A quaint little Railway".[2]

Locomotives and rolling stock

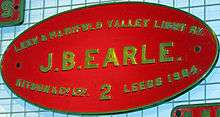

The company only had two locomotives: outside-cylindered 2-6-4Ts, built by Kitson & Co. of Leeds in 1904,[3] which were the first 2-6-4T locomotives to run in Britain - the first standard gauge examples being the Great Central Railway's Class 1B of 1914.[4] Number 1 was named E.R. Calthrop, after the line's engineer, and number 2 was named J.B. Earle (the resident engineer). Due to the influence of Calthrop, the locomotives had a somewhat colonial appearance with large headlights which were never used. They also had fittings for cow catchers - again never fitted, and they sported rerailing jacks by the smokebox. The locos were originally painted brown with gold and black lining, after the grouping replaced by crimson lake with gold and black lining. Latterly, after the Great Depression had set in, they ran in plain black.

There was no turntable on the line, and engines ran chimney first towards Waterhouses,[3] despite initial concerns (usually engines on a gradient run the other way, to keep the water over the firebox crown) about the steeper down section (1 in 40) out of Waterhouses. In latter years E.R. Calthrop returned from repairs in Crewe facing the other way, as can be seen in later photographs.

There were four coaches; two first class and two brake composite thirds. These were originally painted primrose yellow, and later repainted in LMS Midland red.

Freight wagons consisted of one box van and two open wagons. These open wagons were built by the Leeds Forge Company and were largely designed for the transport of loose milk churns.

Additionally there were also five (four short and one long) transporter wagons, technically "low side bogie goods wagons". These were supplied by the Cravens Railway Carriage & Wagon Company at a cost of £315 each. Uniquely in Britain, in a piggy-back style these were capable of carrying standard gauge wagons - particularly milk tankers and coal wagons - to standard gauge sidings along the route. However, the extra height and width of the loading gauge caused by this arrangement (such as seen in the dimensions of Swainsley Tunnel) undid some of the benefits of using a narrow gauge. This arrangement also meant that standard gauge lengths of track (on sidings) had to be constructed level with the rails of the low transporters.

Frequency of service

Trains started and finished at Hulme End, at the northern end of the line, where the engine sheds were located.

After opening, there were initially three trains daily in each direction. This increased to four on Thursdays and Saturdays (and later to five). After an attempt by the North Staffordshire Railway as early as 1904 to reduce the service during the winter months to a service only on Wednesdays and Saturdays, the Manifold Company secured an agreement that there should be a minimum of two trains in each direction throughout the year. On Bank Holidays there were some seven trains daily, and at peak times both engines and all carriages/wagons would be in use - planks and awnings were placed on the open wagons to make them usable by passengers, albeit rather rudimentary. It is recorded that in Whit Week in 1905 some 5000 passengers were carried, and the most intensive service saw trains operating from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Sunday services began in 1905, but stopped in 1930, thus losing much tourist revenue.

The most important traffic on the line was from the Express Dairies creamery at Ecton. Most of the product was destined via dedicated milk trains for London.[5] In 1911 222,598 imperial gallons (1,011,950 L) were brought in from the L&MVLR growing to 717,332 imperial gallons (3,261,060 l) in 1922. Initially all the milk was carried in milk churns, which had to be manhandled across the platforms at Waterhouses. But after the First World War the churns were loaded into standard gauge vans taken to and from Ecton on the transporter wagons.[6] Eventually milk tankers were also used, again being transferred between Ecton and Waterhouses on the transporters.[6] The importance of the milk traffic was such that between 1919 and 1926, special milk trains ran direct between Waterhouses and London, rather than the vans being shunted between various trains until the milk reached its ultimate destination.[5] The year after the closure of the creamery in 1933, the L&MVLR closed.

Closure

In 1932 Express Dairies closed its Ecton creamery, concentrating on its new Rowsley creamery, re-routing milk collection in the area to road transport. The loss of this milk trade removed most of the goods traffic from the line. Furthermore, the developing motor bus services served the villages much better, these settlements being largely on the hills, and often some distance from the line itself. The railway closed briefly in consequence, to re-open briefly in 1933, but closed finally to all traffic on Monday 10 March 1934.

J.B.Earle was cut up at the LMSR Crewe railway works, whilst E.R. Calthrop was used in the track-removal train, which worked south from Hulme End, before being itself cut up at Waterhouses. All that remains of the engines are three name plates.

The line today – The Manifold Way

The Manifold Valley footpath and cycle way (now called the Manifold Way) was opened in July 1937 after the LMS handed over the trackbed to Staffordshire County Council. It continues on to Waterhouses, via Hulme End, as a bridle path, and, being tarmacked throughout, is ideal for wheelchair users, prams, etc. For about 1 1⁄2 miles (2.4 km), near Wetton Mill, the route is shared with motor traffic where the C-road has been diverted, and this section includes Swainsley tunnel, built by Sir Thomas Wardle who, despite being a shareholder in the railway, did not want to see it crossing his land. Some spectacular scenery can be found along the eight-mile (13 km) route, including Thor's Cave, Wetton Hill and Beeston Tor. Many consider that this section bears comparison with the better-known Dovedale a few miles to the east. (The National Trust own several of these sites, as part of their South Peak Estate.)

The Old Light Railway Hotel at Hulme End is now called the Manifold Inn. There are campsites at Hulme End and Wetton Village.

At Ecton Hill a 4,000-year-old copper mine lies along the route; there is still evidence of the railway's loading platforms along the route of the old railway. A dairy once stood here and one can still see where milk churns were once loaded onto the morning milk train. The Ecton dairy was famous for its Stilton cheese.

The old engine shed at Hulme End opened as a cafe called The Tea Junction in 2010.

Modelling

Slater's Plasticard[7] produce an O16.5 scale kit of the locomotives, with Dorset Kits offering brass coach construction kits together with etched brass kits for both long and short transporter wagons, the open bogie wagons and the bogie van to match in this scale. These can all be built to run on the correct 17.5mm track.

PortWynnstay[8] models of Derby offer a resin outline of the short wheelbase transport car/wagon.

Meridian Models recently produced an (009) scale locomotive body in white metal to fit on a (Minitrix) chassis and Worsley Works produce a basic scratch kit for the carriages, requiring addition of bogies (where applicable), couplings, door handles, and interior to complete. A third company has apparently produced the transporter cars/wagons in this scale.

Roundhouse[9] has produced a live steam model in 1:19 scale, (16mm/foot), of the Kitson 2-6-4 locomotive in the NSR livery.

There is a model at the visitors' centre in Hulme End along one wall inside the former station building. This shows a representation of Hulme End station, yard and nearby buildings in (009) scale with a short run (scaled down distance) to a model of Butterton station.

See also

- British narrow gauge railways

- Cycleways in England

- Rail trails

- 2 ft 6 in gauge railways

References

Notes

- "Leek and Manifold Light Railway". Bradshaw's Railway Manual, Shareholder's Guide, and Official Directory. W.J. Adams. 1905.

- "Long-closed staffordshire railway in action 'A Quaint Little Railway' (1930)". British Film Institute. 10 October 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Jenkins 1991, p. 77

- Haresnape & Rowledge 1982, p. 106

- Jeuda, Basil (1980). The Leek, Caldon & Waterhouses Railway. Cheddleton, Staffordshire: North Staffordshire Railway Company (1978). ISBN 0-907133-00-2.

- "Manifold" (1965). The Leek & Manifold Valley Light Railway (2nd ed.). Truro, Cornwall: D Bradford Barton.

Bibliography

- Bradshaw's General Railway and Steam Navigation Guide for Great Britain and Ireland. Manchester: Henry Blacklock & Co. June 1922.

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Christiansen, Rex; Miller, Robert William (1971). The North Staffordshire Railway. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5121-4.

- Christiansen, Rex (1997). Portrait of the North Staffordshire Railway. Shepperton, Surrey: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2546-0.

- Jeuda, Basil (1980). The Leek, Caldon & Waterhouses Railway. Cheddleton, Staffordshire: North Staffordshire Railway Company (1978). ISBN 0-907133-00-2.

- "Manifold" (1965). The Leek & Manifold Valley Light Railway (2nd ed.). Truro, Cornwall: D Bradford Barton.

- Ranson, Philip J G (1981). The archaeology of railways. World's Work. ISBN 0-437-14401-1.

- Haresnape, Brian; Rowledge, Peter (May 1982). Robinson Locomotives: A Pictorial History. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-1151-6. DX/0582.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, S.C. (1991). The Leek and Manifold Light Railway. Locomotion Papers. Headington: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-414-8. LP179.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Jenkins, S.C. Leek and Manifold Light Railway (video)

- Porter, L. (1997) Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway ISBN 1-873775-20-2

- Gratton, R. (2005) The Leek and Manifold Light Railway ISBN 0-9538763-7-3

- Keys R and Porter L (1972) The Manifold Valley and its Light Railway, Moorland publishers

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leek and Manifold Valley Light Railway. |