Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran

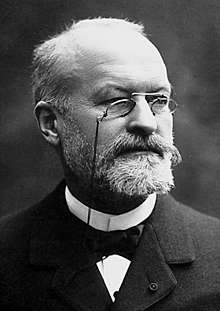

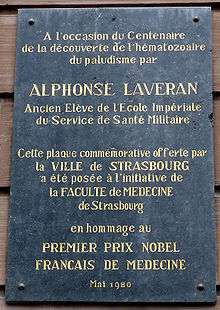

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (18 June 1845 – 18 May 1922) was a French physician who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907 for his discoveries of parasitic protozoans as causative agents of infectious diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis. Following his father, Louis Théodore Laveran, he took up military medicine as his profession. He obtained his medical degree from University of Strasbourg in 1867.

Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 June 1845 |

| Died | 18 May 1922 (aged 76) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière du Montparnasse 48.84°N 2.33°E |

| Nationality | France |

| Alma mater | University of Strasbourg |

| Known for | Trypanosomiasis, malaria |

| Spouse(s) | Sophie Marie Pidancet |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1907) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Tropical medicine Parasitology |

| Institutions | School of Military Medicine of Val-de-Grâce Pasteur Institute |

| Signature | |

| |

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, he joined the French Army. At the age of 29 he became Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce. At the end of his tenure in 1878 he worked in Algeria, where he made his major achievements. He discovered that the protozoan parasite Plasmodium was responsible for malaria, and that Trypanosoma caused trypanosomiasis or African sleeping sickness.[1] In 1894 he returned to France to serve in various military health services. In 1896 he joined Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service, from where he received the Nobel Prize. He donated half of his Nobel prize money to establish the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908, he founded the Société de Pathologie Exotique.[2]

Laveran was elected to French Academy of Sciences in 1893, and was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1912.

Early life and education

Alphonse Laveran was born at Boulevard Saint-Michel in Paris, to parents Louis Théodore Laveran and Marie-Louise Anselme Guénard de la Tour Laveran.[3] He was an only son with one sister. His family was in a military environment. His father was an army doctor and a Professor of military medicine at the École de Val-de-Grâce. His mother was the daughter of an army commander. At a young age his family went to Algeria to accompany his father's service. He was educated in Paris, and completed his higher education from Collège Saint Barbe and later from the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. Following his father he chose military medicine and entered the Public Health School at Strasbourg in 1863. In 1866 he became a resident medical student in the Strasbourg civil hospitals. In 1867 he submitted a thesis on the regeneration of nerves and earned his medical degree from the University of Strasbourg.[4]

Career

Laveran was Medical Assistant-Major of the French Army at the time of Franco-Prussian War. He was posted to Metz, where the French were eventually defeated and the place occupied by Germans. He was sent to work at Lille hospital and then to the St Martin Hospital (now St Martin's House) in Paris. In 1874 he qualified a competitive examination by which he was appointed to the Chair of Military Diseases and Epidemics at the École de Val-de-Grâce, a position his father had occupied. His tenure ended in 1878 and he was sent to Algeria, where he remained until 1883. From 1884 to 1889 he was Professor of Military Hygiene at the École de Val-de-Grâce. In 1894 he was appointed Chief Medical Officer of the military hospital at Lille and then Director of Health Services of the 11th Army Corps at Nantes. By then he was promoted to the rank of Principal Medical Officer of the First Class. In 1896 he entered the Pasteur Institute as Chief of the Honorary Service to pursue a full-time research on tropical diseases.[4]

Discoveries

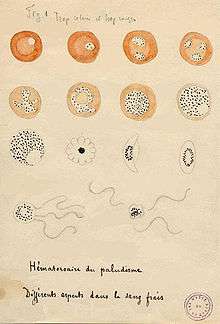

In 1880, while working in the military hospital in Constantine, Algeria, he discovered that the cause of malaria is a protozoan, after observing the parasites in a blood smear taken from a patient who had just died of malaria.[5] He found the causative organism to be a protozoan which he named Oscillaria malariae, but later renamed Plasmodium.[6][7] This was the first time that protozoans were shown to be a cause of disease of any kind. The discovery was therefore a validation of the germ theory of diseases.[8]

Laveran later worked on the trypanosomes, particularly sleeping sickness, and showed once again that protozoans were responsible for the disease.[9]

Awards and honours

Laveran was awarded the Bréant Prize (Prix Bréant) of the French Academy of Sciences in 1889 and the Edward Jenner Medal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1902 for his discovery of the malarial parasite. He received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1907. He gave half the Prize for foundation of the Laboratory of Tropical Medicine at the Pasteur Institute. In 1908 he founded the Société de pathologie exotique, over which he presided for 12 years. He was elected to membership in the French Academy of Sciences in 1893, and was conferred Commander of the National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1912. He was Honorary Director of the Pasteur Institute in 1915 on his 70th birthday. He was elected President of the French Academy of Medicine in 1920. His work was commemorated philatelically on a stamp issued by Algeria in 1954.[7]

Personal life and death

Laveran married Sophie Marie Pidancet in 1885. They had no children.[3]

In 1922 he suffered from an unspecified illness for some months and died in Paris.[10][11] He is interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris. He was an atheist.[12]

Recognition

Laveran's name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.[13]

Works

Laveran was a solitary but dedicated researcher and he wrote more than 600 scientific communications. Some of his major books are:[14][15]

- Nature parasitaire des accidents de l'impaludisme, description d'un nouveau parasite trouvé dans le sang des malades atteints de fièvre palustre. Paris 1881

- Traité des fièvres palustres avec la description des microbes du paludisme. Paris 1884

- Traité des maladies et épidémies des armées. Paris 1875

- Trypanosomes et Trypanosomiases . Masson, Paris 1904 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

References

- Nye, Edwin R (2002). "Alphonse Laveran (1845–1922): discoverer of the malarial parasite and Nobel laureate, 1907". Journal of Medical Biography. 10 (2): 81–7. doi:10.1177/096777200201000205. PMID 11956550.

- Garnham, PC (1967). "Presidential address: reflections on Laveran, Marchiafava, Golgi, Koch and Danilewsky after sixty years". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 61 (6): 753–64. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(67)90030-2. PMID 4865951.

- Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2007). Encyclopedia of World Scientists (Revised ed.). New York (US): Facts on File. pp. 427–428. ISBN 978-1-43-811882-6.

- "Alphonse Laveran – Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Bruce-Chwatt LJ (1981). "Alphonse Laveran's discovery 100 years ago and today's global fight against malaria". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 74 (7): 531–536. doi:10.1177/014107688107400715. PMC 1439072. PMID 7021827.

- Cox, Francis EG (2010). "History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors". Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. PMC 2825508. PMID 20205846.

- Haas, L F (1999). "Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran (1845-1922)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 67 (4): 520. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.4.520. PMC 1736558. PMID 10486402.

- Sherman, Irwin (2008). Reflections on a Century of Malaria Biochemistry. London: Academic Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-0809-2183-9.

- Sundberg, C (2007). "Alphonse Laveran: the Nobel Prize for Medicine 1907". Parassitologia. 49 (4): 257–60. PMID 18689237.

- Nobel Lectures, Physiology or Medicine 1901-1921. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company. 1967. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Alphonse Laveran - Facts". Nobel Media AB. 2014.

- Smith, Warren Allen (1 January 2000). Who's who in Hell: A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-theists. Barricade Books. p. 648. ISBN 9781569801581. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Behind the Frieze". LSHTM. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- "Laveran, Alphonse, 1849-1922 [books by]". Internet Archive. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- "Online Books by Alphonse Laveran". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran. |

- Alphonse Laveran on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on December 11, 1907 Protozoa as Causes of Diseases

- CDC profile

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Faqs.org profile

- Encyclopedia of World Biography

- Timeline of Laveran at Pasteur Institute