Lauria Nandangarh

Lauria Nandangarh, also Lauriya Navandgarh, is a city or town about 14 km from Narkatiaganj (or Shikarpur) and 28 km from Bettiah in West Champaran district of Bihar state in northern India.[1] It is situated near the banks of the Burhi Gandak River. The village draws its name from a pillar (laur) of Ashoka standing there and the stupa mound Nandangarh (variant Nanadgarh) about 2 km south-west of the pillar. Lauriya Nandangarh is a historical site located in West Champaran district of Bihar.[1] Remains of Mauryan period have been found here.[1]

Lauria Nandangarth | |

|---|---|

City/town | |

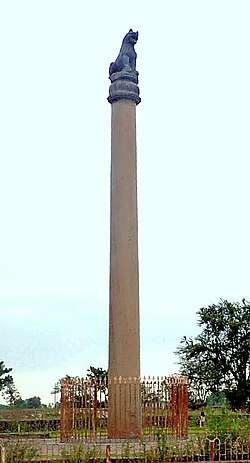

The Pillar of Ashoka at Lauria Nandangarh. Another recent photograph here. | |

Lauria Nandangarth Location in Bihar, India  Lauria Nandangarth Lauria Nandangarth (Bihar) | |

| Coordinates: 26°59′54.52″N 84°24′30.52″E | |

| Country | |

| State | Bihar |

| District | West Champaran |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bhojpuri, Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 845453 |

| Nearest city | Bettiah |

| Lok Sabha constituency | Valmikinagar |

| Vidhan Sabha constituency | Lauriya Yogapatti |

History & Archaeological Excavations

Lauriya has 15 Stupa mounds in three rows, each row upwards of 600 m; the first row begins near the pillar and goes E to W, while the other two are at right angles to it and parallel to each other.[1]

Alexander Cunningham partially excavated one of them in 1862 and found a retaining wall of brick (size 51 X 20 cm).[1] A few years later Henry Bailey Wade Garrick excavated several mounds with indifferent results. In 1905 T. Block excavated four mounds, two in each of the N to S rows.[1] In two of them, he found at the center of each, at a depth of "1.8 m to 3.6 m" (probably meaning 1.8 m in one and 3.6 m in the other) a gold leaf with a female figurine standing in frontal pose and a small deposit of burnt human bones mixed with charcoal.[1] The core of the mounds was, according to him, built of layers of yellow clay, a few centimeters in thickness, with grass leaves laid between.[1] Further down in one of them he found the stump of a tree.[1] His conclusions were that the earthen barrows had some connection with the funeral rites of the people who erected them, and he found an explanation of the phenomena encountered by him in the rites of cremation and post-cremation prescribed in the Vedas. On the basis of this hypothesis he identified the gold female figurine as the earth goddess Prithvi and ascribed the mounds to a pre-Mauryan age. After him the mounds came to be known loosely as "Vedic burial mounds". The locals call these mounds Bhisa, a word also recorded by Cunningham.[2] Some believe that the 26-metre-high ancient brick sepulchral mound is the stupa where the ashes of Lord Buddha were enshrined.[3][4]

In 1935-36, archaeologist Nani Gopal Majumdar re-examined the four mounds with important results.[1] He found that all of them were earthen burial memorials with burnt brick revetments, two being faced with a brick lining in a double tier, so that there was no justification of regarding them as mere earthen barrows.[1] He also pointed out that the golden leaves found by Block had their exact replica in the Stupa at Piprahwa which is definitely a Buddhist Stupa of 300 B.C. or earlier. The respective Lauriya Stupas might be of a comparable date and there is nothing to connect them with Vedic burial rites. The layers of yellow clay which had a share in the building up of the Vedic theory of Block, are according to observations of archaeologist Amalananda Ghosh, nothing but mud bricks, husk and straw being a common ingredient in ancient brick.

Excavation of the Nandangarh site was started by Majumdar in 1935 and continued by Ghosh until 1939.[1] Before excavation the mound had a height of 25 m and a circumference of about 460 m, standing at the East of a brick fortification about 1.6 km in perimeter and roughly oval of plan, no doubt enclosing a habitation area, perhaps the headquarters of a clan that was responsible for the erection of the Lauriya Stupas. Surface finds indicate that it was inhabited in Shunga (if not earlier) and Kushans times.[1]

On excavation, Nandangarh turned out to be stupendous Stupa with a polygonal or cruciform base;[1][5][6] with its missing dome which must have been proportionately tall, the Stupa must have been one of the highest in India.[7]

The walls of the four cardinal directions at the base (only the W ones and partly the S ones were excavated) are each 32 m long and the wall between each has a zigzag course with 14 re-entrant and 13 outer angles. The walls flanking the first and second terraces following the polygonal plan of the base; those pertaining to the upper terraces were circular. An extensive later restoration hid the four upper walls and provided new circular ones; the polygonal plan of the walls of the base and the first terrace were left unaltered. The top of each terrace served as a pradakshina-path (South facing pathway), though no staircase to reach the top was found in the excavated portion.

The core of the stupa consists of a filling of earth with a large number of animal and human figurines in the Shunga and Kushana idiom, a few punch marked coins and cast copper coins, terracotta sealing of the 2nd and 1st century B.C. and iron objects.[1] As the earth was brought from outside, obviously from a part of the habitation area to the south of the stupa where the resultant pond is still visible, the objects are understandably not stratified.

In a shaft dug into center of the mound an undisturbed filling was found at a depth of 4.3 m the remains of a brick altar 1 m high; it has previously been truncated, perhaps by one of the explorers of the 19th and the early 20th centuries. Further down at a depth of 4.6 m from the bottom of the altar the top of an intact, miniature stupa was found, complete with a surmounting square umbrella.[1] This stupa is 3.6 m high and polygonal on plan.[1] An examination of its interior yielded nothing meaningful, but beside there lay a tiny copper vessel with a lid fastened to it by a wire. Inside the vessel was a long strip of the birch leaf manuscript, which having been squeezed into it was so fragile that it was impossible to spread it out and examine thoroughly without damaging it. The bits that could be extricated showed Buddhist text (probably the Pratītyasamutpāda since the word nirodha could be read a few times) written in characters of the 4th century A.D. No excavations were made at a further depth.[1]

Pillar of Ashoka

Less than half a kilometer from the village and 2 km from the mound, stands the famous pillar of Ashoka.[8] It is a single block of polished sandstone over 32 feet (10 m) high. The top is bell shaped with a circular abacus ornamented with Brahmi geese supporting the statue of a lion.[9]

The pillar is inscribed with the edicts of Ashoka in clear and beautifully cut characters.[10] The lion has been chipped in the mouth and the column bears the mark of time just below the top which has itself been slightly dislodged. Signs of vandalism over the years are clearly visible.

Photographed in 1911.

Photographed in 1911. Close view of the inscriptions.

Close view of the inscriptions. Edicts.

Edicts. Edicts.

Edicts. Frontal close-up of the lion (jaws broken). The geese of the abacus are clearly visible.

Frontal close-up of the lion (jaws broken). The geese of the abacus are clearly visible.

See also

References

- "Archaeological Survey Of India; Excavations - Important - Bihar". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Report of Tours in North and South Bihar in 1880-81. Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- "Lauria NandanGarh'". Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- Prasad, Dr Rajendra (1928). Satyagraha In Champaran. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 20. ISBN 9788184301748.

- Kaushik, Garima (2016). Women and Monastic Buddhism in Early South Asia: Rediscovering the Invisible Believers. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9781317329398.

- Pande, Govind Chandra (2006). India's Interaction with Southeast Asia. Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture. p. 419. ISBN 9788187586241.

- An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. BRILL. 1990. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Vishnu, Asha (1993). Material Life of Northern India: Based on an Archaeological Study, 3rd Century B.C. to 1st Century B.C. Mittal Publications. p. 175. ISBN 9788170994107.

- "Lauria Nandangarh". Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- Ray, Niharranjan (1975). Maurya and Post-Maurya Art: A Study in Social and Formal Contrasts. Indian Council of Historical Research. p. 19.

| Edicts of Ashoka (Ruled 269–232 BCE) | |||||

| Regnal years of Ashoka |

Type of Edict (and location of the inscriptions) |

Geographical location | |||

| Year 8 | End of the Kalinga war and conversion to the "Dharma" |  Udegolam Nittur Brahmagiri Jatinga Rajula Mandagiri Yerragudi Sasaram Barabar Kandahar (Greek and Aramaic) Kandahar Khalsi Ai Khanoum (Greek city) | |||

| Year 10[1] | Minor Rock Edicts | Related events: Visit to the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya Construction of the Mahabodhi Temple and Diamond throne in Bodh Gaya Predication throughout India. Dissenssions in the Sangha Third Buddhist Council In Indian language: Sohgaura inscription Erection of the Pillars of Ashoka | |||

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (in Greek and Aramaic, Kandahar) | |||||

| Minor Rock Edicts in Aramaic: Laghman Inscription, Taxila inscription | |||||

| Year 11 and later | Minor Rock Edicts (n°1, n°2 and n°3) (Panguraria, Maski, Palkigundu and Gavimath, Bahapur/Srinivaspuri, Bairat, Ahraura, Gujarra, Sasaram, Rajula Mandagiri, Yerragudi, Udegolam, Nittur, Brahmagiri, Siddapur, Jatinga-Rameshwara) | ||||

| Year 12 and later[1] | Barabar Caves inscriptions | Major Rock Edicts | |||

| Minor Pillar Edicts | Major Rock Edicts in Greek: Edicts n°12-13 (Kandahar) Major Rock Edicts in Indian language: Edicts No.1 ~ No.14 (in Kharoshthi script: Shahbazgarhi, Mansehra Edicts (in Brahmi script: Kalsi, Girnar, Sopara, Sannati, Yerragudi, Delhi Edicts) Major Rock Edicts 1-10, 14, Separate Edicts 1&2: (Dhauli, Jaugada) | ||||

| Schism Edict, Queen's Edict (Sarnath Sanchi Allahabad) Lumbini inscription, Nigali Sagar inscription | |||||

| Year 26, 27 and later[1] |

Major Pillar Edicts | ||||

| In Indian language: Major Pillar Edicts No.1 ~ No.7 (Allahabad pillar Delhi pillar Topra Kalan Rampurva Lauria Nandangarh Lauriya-Araraj Amaravati) Derived inscriptions in Aramaic, on rock: | |||||