Girnar

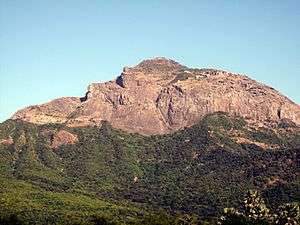

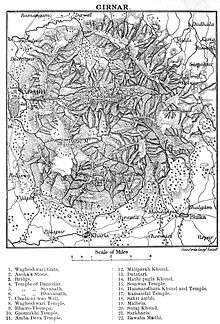

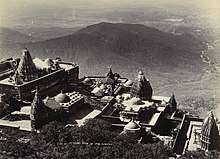

The group temples of Jainism are situated on the Mount Girnar situated near Junagadh in Junagadh district, Gujarat, India. There temples are sacred to the Digambara and the Svetambara branches of Jainism. Girnar, also known as Girinagar ('city-on-the-hill') or Revatak Parvata, is a group of mountains in the Junagadh District of Gujarat, India.[1]

| Mount Girnar | |

|---|---|

| ગિરનાર પર્વત Girinagar Revatak Parvata | |

Mount Girnar from Bhavnath | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,069 m (3,507 ft) |

| Listing | List of Indian states and territories by highest point |

| Coordinates | 21°29′41″N 70°30′20″E |

| Geography | |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Igneous |

Geology

At the peak of Mount Girnar, This Place belongs to Jainns. which are considered sacred by people of the Jain community.This place is sacred to the Jains because it is the place where Lord Niminatha went to attain salvation. His footprint is still on the 5th token of Girnar. There is a place where they sit for penance. From there he had gone to salvation. there is the Dattatreya Temple, which is home to the footprints of Lord Dattatreya. An idol of Lord Dattatreya sits inside the temple. Girnar Parvat has a terrain different from the golden sands of Gujarat and the verdant Gir Forest making it absolutely unique. Devotees visit Girnar Parvat all year round, and Datar Peak is considered to be sacred by both Hindus and Muslims.

History

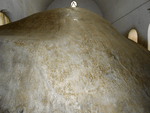

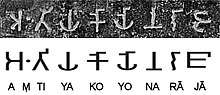

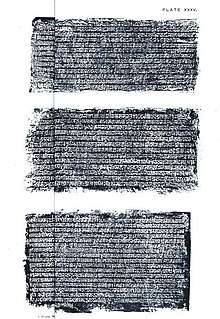

Ashoka's edicts at Mount Girnar, Junagadh

Fourteen of Ashoka's Major Rock Edicts, dating to circa 250 BCE, are inscribed on a large boulder that is housed in a small building located outside the town of Junagadh on Saurashtra peninsula in the state of Gujarat, India. It is located on Girnar Taleti road, at about 2 km (1.2 mi) far from Uperkot Fort easterly, some 2 km before Girnar Taleti. An uneven rock, with a circumference of seven meters and a height of ten meters, bears inscriptions etched with an iron pen in Brahmi script in a language similar to Pali and date back to 250 BCE, thus marking the beginning of written history of Junagadh.[2]

On the same rock there are inscriptions in Sanskrit added around 150 CE by Mahakshatrap Rudradaman I, the Saka (Scythian) ruler of Malwa, a member of the Western Satraps dynasty (see Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman).[2] The edict also narrates the story of Sudarshan Lake which was built or renovated by Rudradaman I, and the heavy rain and storm due to which it had broken.[3]

Another inscription dates from about 450 CE and refers to Skandagupta, the last Gupta Empire.[3]

The protective building around the edicts was built in 1900 by Nawab Rasool Khan of Junagadh State at a cost of Rs 8,662. It was repaired and restored in 1939 and 1941 by the rulers of Junagadh. The wall of the structure had collapsed in 2014.[4]

A much smaller replica of these Girnar edicts has been positioned outside the entrance of the National Museum in Delhi.[5]

Similarly, inside the Parliament Museum at New Delhi, an exhibit replicates the act of artists sculpting inscriptions of Girnar edict on a rock.[6]

Housing for Ashoka's edicts.

Housing for Ashoka's edicts. The rock with inscriptions.

The rock with inscriptions. Rubbing of part of the inscriptions.

Rubbing of part of the inscriptions.

In Jainism

According to Jain religious beliefs, Neminath, the 22nd Tirthankara Neminath became an ascetic after he saw the slaughter of animals for a feast on his wedding. He renounced all worldly pleasures and came to Mount Girnar to attain salvation. He attained omniscience and Moksha (died) on the Mount Girnar. His bride-to-be Rajulmati also renounced and became a nun.

Jain Temples

Girnar was anciently called Raivata or Ujjayanta, sacred amongst the Jains to Neminath, the 22nd Tirthankar, and a place of pilgrimage before 250 BCE.[8]

Situated on the first plateau of Mount Girnar at the height of about 3800 steps, at an altitude of 2370 ft above Junagadh, still some 600 ft below the first summit of Girnar, there are Jain temples with marvelous carvings in marble.[8][9]

Some 16 Jain temples here form a sort of fort on the ledge at the top of the great cliff. These temples are along the west face of the hill, and are all enclosed.

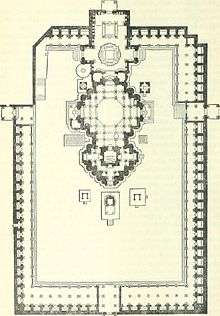

On entering the gate, the large enclosure of the temples is on the left, while to the right is the old granite temple of Man Singh, Bhoja Raja of Kutch, and farther on the much larger one of Vastupala. Built into the wall on the left of the entrance is an inscription in Sanskrit. Some 16 Jain temples here form a sort of fort on the ledge at the top of the great cliff, but still 600 feet below the summit. The largest temple is the Neminath temple, standing in a quadrangular court 195 x 130 feet. It was built from 1128 to 1159. It consists of two halls (with two porches, called the mandapas), and a shrine, which contains a large black image of Neminatha, the 22d Tirthankara. Around the shrine is a passage with many images in white marble. Between the outer and inner halls are two shrines. The outer hall has two small raised platforms paved with slabs of yellow stone, covered with representations of feet in pairs called padukas, which represent the 2452 feet of the Ganadharas, first disciples of Tirthankaras. On the west of this is a porch overhanging the perpendicular scarp. On two of the pillars of the mandapam are inscriptions dated 1275, 1281, and 1278—dates of restoration. The enclosure is nearly surrounded inside by 70 cells, each enshrining a marble image, with a covered passage in front of them lighted by a perforated stone screen.

The principal entrance was originally on the east side of the court, but it is now closed, and the entrance from the court in Khengar's Palace is that now used. There is a passage leading into a low dark temple, with granite pillars in lines. Opposite the entrance is a recess containing two large black images; in the back of the recess is a lion rampant, and over it a crocodile in bas-relief. Behind these figures is a room from which is a descent into a cave, with a large white marble image which is mostly concealed by priests. It has a slight hollow in the shoulder, said to be caused by water dropping from the ear, whence it was called Amijhara, "nectar drop."[10] Neminath is said to have attained Moksha from Girnar so this place is frequently noted in Jain literature.[11]

In the North porch are inscriptions which state that in Samwat 1215 certain Thakurs completed the shrine, and built the Temple of Ambika.

After leaving this there are three temples to the left that on the south side contain a colossal image of Rishabha Deva, the first Tirthankar, exactly like that at Palitana temples, called Bhim-Padam. On the throne of this image is a slab of yellow stone carved in 1442, with figures of the 24 Tirthankars.[10]

Opposite this temple is a modern one to Panchabai. West of it is a large temple called Malakavisi or Meravasi, sacred to Parshwanath, built in the 15th century. North of this is another temple of Parshwanath, which contains a large white marble image canopied by a cobra, whence it is called Sheshphani, an arrangement frequently found in the South India but uncommon in North India. It bears a date of 1803. The last temple to the north is Kumarpal's temple, built by Chaulukya king Kumarapala, which has a long open portico on the west. It appears to have been destroyed by the Muslims, and restored in 1824 by Hansraja Jetha. These temples are along the west face of the hill, and are all enclosed.[10]

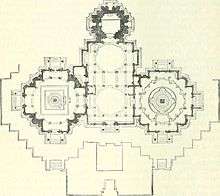

Outside to the north is the Bhima Kunda, a tank 70 feet by 50 feet, in which Hindus bathe. Immediately behind the temple of Neminath is the triple one temple, Vastupala-Tejpala temple, erected by the brothers Tejapala and Vastupala (built in 1177), who also built the Dilwara Temples on Mount Abu. The plan is that of three temples joined together. The shrine has a blue black image of Mallinath, the 19th Tirthankar. Farther north is the temple of Samprati Raja, This temple is probably one of the oldest on the hill, dating to 1158. Samprati is said to have ruled at Ujjain in the end of the third century BCE, and to have been the son of Kunala, Ashoka's third son.[10]

Neminath Temple

The Neminath temple is the largest temple of the group standing in a quadrangular court 195 x 130 feet.[8][9] The temple was rebuilt completely by Sajjana, the governor of Saurashtra appointed by Jayasimha Siddharaja, in 1129 CE.[12] There is an inscription on one of the pillars of the mandapa stating that it was repaired in 1278 CE.[9]

It consists of two rangamandapa halls with two porches and a central shrine (Gudhamandapa), which contains a large black image of Neminath sitting in the lotus position holding a conch in his palm.[8][9]

The principal hall in front of the central shrine measures across from door to door inside 41' 7" x 44' 7" from the shrine door to that leading out at the west end. The roof is supported by 22 square columns of granite coated with white lime while the floor is of tessellated marble.[9]

Round the central shrine is a circumambulatory passage (pradakshina) with many images in white marble including that of a Ganesha and a Chovishi or slab of the twenty four Tirthankara.[8][9] Between the outer and inner halls are two shrines.[9]

The outer hall measures 38' x 21' 3". The outer hall has two small raised platforms paved with slabs of yellow stone, covered with representations of feet in pairs called padukas, which represent the 2452 feet of the Gandharas, first disciples of Tirthankaras.[9]

On the west of this is a closed entrance with a porch overhanging the perpendicular scarp of the hill.[9] On two of the pillars of the mandapa are inscriptions dated 1275, 1281, and 1278 — dates of restoration.

The enclosure in which these rangamandapas and the central shrine are situated, is nearly surrounded inside by 70 little cells, each enshrining a marble image on a bench, with a covered passage running round in front of them lighted by a perforated stone screen.[9]

The principal entrance was originally on the east side of the court; but it is now closed, and the entrance from the south side of court in Khengar's Palace is that now used.[9]

On south side, there is a passage leading into a low dark temple, with granite pillars in lines. Opposite the entrance is a recess containing two large black images; in the back of the recess is a lion rampant, and over it a crocodile in bas-relief. Behind these figures is a room from which is a descent into a cave, with a large white marble image which is mostly concealed. It has a slight hollow in the shoulder, said to be caused by water dropping from the ear, whence it was called Amijhara, "nectar drop".[13][8] There are few shrines in the court dedicated to Jain monks. In the North porch are inscriptions which state that in Samwat 1215 certain Thakurs completed the shrine, and built the Temple of Ambika.[13]

There is a small temple of Adinath behind the Neminath temple facing west which was built by Jagmal Gordhan of Porwad family in VS 1848 under guidance of Jinendra Suri.[9]

Adabadji Adinatha temple

There are three temples to the left of the passage from the north porch of the Neminath temple. Of them, the temple on the south contains a colossal image of Adinatha, the first Tirthankar, exactly like that at Palitana temples. The image is in standing meditating (kausaggiya) position On the throne of this image is a slab of yellow stone carved in 1442, with figures of the 24 Tirthankars.[14]

Panchmeru temple

On the north, opposite the Adabadji temple, there is Panchabai's or Panchmeru temple which was built in VS 1859. It contains five sikhars or spires each enshrining quadruple images.[14]

Meraka-vasahi

West of Panchmeru temple, there is a large temple. The temples is called Malekavasahi, Merakavasahi or Merakavashi due to false identification. Madhusudan Dhaky noted that the Merakavasahi was a small shrine somewhere near east gate of Neminatha temple while the current temple is large one and outside the north gate of the Neminatha temple. Based on its architecture, Dhaky dates the temple to 15th century and notes that it is mentioned as Kharataravasahi built or restored by Bhansali Narpal Sanghavi in the old itineraries of Jain monks. The temple is depicted in the Shatrunjaya-Giranar Patta dated 1451 CE (VS 1507) in Ranakpur temple so it must have built before it. The temple may have been built as early as 1438 CE.[15] Dhaky believes that the temple may have been built on the site of the Satyapuravatara Mahavira's temple built by Vastupala.[16]

According to an anecdote said by modern Jain writers, Sajjana, the minister of Chaulukya king Siddharaja Jayasimha, built the Neminatha temple using the state treasury. When he collected the funds to return as a compensation, the king declined to accept it so the funds were used to built the temple. Dhaky concludes that the anecdote is not mentioned in any early work and is false.[15]

Sahastraphana (thousand hooded) Parshwanatha, the image which was consecrated in 1803 CE (VS 1459) by Vijayajinendra Suri, is currently the central deity in the temple. The temple originally housed the golden image of Mahavira and brass images of Shantinatha and Parshwanatha on its sides.[17]

The east facing temple has 52 small shrines surrounding the central temple. It has an open portico with ceilings with fine carvings. In the bhamti or cloisters surrounding the court, there are also some remarkable designs in carved ceilings. The roof of the rangamandapa has fine carvings. The shrine proper must have been removed and replaced with new one at the end of the sixteenth century or the start of the seventeenth century. It is known that Karmachandra Bachchhavat, minister of the king of Bikaner, had sent a funds to renovate temple in Shatrunjaya and Girnar under Jinachandrasuri IV of Kharatara Gaccha during the reign of Akbar. There is a shrine housing replica of Ashtapada hill in the south, shrine with Shatrunjayavatar in west, behind the main temple, and Samet Shikhar (or Nandishwar Dwipa) in north.[14][18]

Sangram Soni's Temple

North of the Melakavasahi, there is a temple of Parshwanath in the enclosure. The original temple on the site was Kalyanatraya temple dedicated to Neminatha built by Tejapala, brother of Vastupala. This Kalyanatraya contained quadruple images in three tires as the central deity. The new temple on the site was built in 1438 CE (VS 1494) by Oswal Soni Samarasimha and Vyavahari Maladev. The spire of this 15th century temple is replaced by new spire built c. 1803 CE. The temple is now mistakenly known as Sangram Soni's temple.[19] It was repaired by Premabhai Hemabhai about 1843. It contains a large white marble figure of Parswanatha bearing the date 1803 CE with the polycephalous cobra over him whence he is styled Seshphani. This temple is peculiar in having a sort of gallery and like the previous one of the central deity faces the east whilst the others mostly face the west.[14]

Kumarapala's Temple

The last temple to the north is known as the Kumarapala's temple which is falsely attributed to 12th century Chaulukya king Kumarapala. Based on the literary, epigraphic and architectural evidence, Madhusudan Dhaky concluded that the temple belongs to 15th century and was built by Purnasinha Koshthagarika (Punsi Kothari). The central deity was Shantinatha and was consecrated by Jinakirti Suri probably in 1438 CE. The part of the original temple was destroyed by the 18th century and appears to have been restored in 1824 CE by Hansraja Jetha which is known from the inscription.[20]

The temple is west facing. The original temple had 72 shrines surrounding the central temple which no longer exist. The central temple has a modern long open portico supported by twenty four columns. The temple proper or mandapa and shrine are small and the ceilings and architraves are restored. The mandapa with its beautiful pendentive and the pillars and lintels of the portico. The shrine contains three images; in the middle Abhinandana Swami dedicated in 1838 and on either side Adinatha and Sambhavanatha dated 1791.[20][14]

Mansingha Bhojaraja temple

To the east of the Devakota, there are several temples: the principal being the temple of Mansingha Bhojaraja of Kachchh, an old granite temple near the entrance gate which is now dedicated to Sambhavanatha.[21]

Vastupala-vihara

Vastupala-vihara is a triple temple, the central fane measuring 53 feet by 291⁄2 has two domes and finely carved but much mutilated and the shrine which is 13 feet square with a large niche or gokhla on the left side contains an image of Mallinatha. Beneath the image is the inscription mentioning Vastupala and his family members.[21]

On either side this central temple, there is a large hall about 38 feet 6 inches from door to door containing a remarkable solid pile of masonry called a samovasarana that on the north side named Sumeru having a square base and the other Sameta Sikhara with a nearly circular one. Each rises in four tiers of diminishing width almost to the roof and is surmounted by a small square canopy over images. The upper tiers are reached by steps arranged for the purpose. On the outside of the shrine tower are three small niches in which images have been placed and there are stone ladders up to the niches to enable the pujaris to reach them.[22] The temple was completed in 1232 CE. There are six large inscriptions of Vastupala in the temple dated VS 1288. Originally Shatrunjayavatara Adinatha was the central deity of the temple. The roofs of temple were rebuilt in the 15th century.[23]

There is another temple on the cliff behind the Vastupala-vihara which is now known as Gumasta temple. The temple was built by Vastupala and was dedicated to Marudevi. Another shrine behind Vastupala-vihara is dedicated to Kapardi Yaksha.[12]

Samprati Raja temple

Farther north of the Vastupala-vihara, the Samprati Raja temple is situated. The temple was built in 1453 (VS 1509) CE by Shanraj and Bhumbhav from Khambhat. It was originally dedicated to Vimalanatha.[24] According to Dhaky, the temple was built on the site of Stambhanatirthavatara Parshwanatha temple built by Vastupala.[16] The temple is mistakenly attributed to Maurya ruler Samprati.[16]

It is built against the side of a cliff and is ascended to by a stair. Inside the entrance there is another very steep flight of steps in the porch leading up to a large mandapa to the east of which is added a second mandapa and a gambhara or shrine containing a black image of Neminatha dedicated by Karnarama Jayaraja in 1461.[25]

Other temples

.jpg)

To the east of Vastupala vihara and Samprati Raja temples, and on the face of the hill above, there are other temples among them an old one going by the name of Dharmasa of Mangrol or Dharamchand Hemchand built of grey granite the image being also of granite. Near it is another ruined shrine in which delicate granite columns rise from the corners of the sinhasana or throne carved with many squatting figures. Near this is the only shrine on this mount to Mahavira.[26]

South of this, and 200 feet above the Jain temples on way to the first summit, is the Gaumukhi Shrine, near a plentiful spring of water.[8]

Away on the north, climbing down the steps, there are two shrines dedicated to Neminatha in Sahsavan where he said to have taken renunciation and attained omniscience. Neminatha is said to have attained Nirvana or died on the highest peak of the Girnar. There is a modern Samovasarana temple.

Tanks

Outside to the north of the Kumarapala's temple, there is the Bhima Kunda, a tank measuring 70 feet by 50 feet. Below it and on the verge of the cliff is a smaller tank of water and near it a small canopy supported by three roughly hewn pillars and a piece of rock containing a short octagonal stone called Hathi pagla or Gajapada, the elephant foot, a stratum on the top of which is of light granite and the rest of dark the lower part is immersed in water most of the year.[21]

Five Peaks

There are 5 tonks on the Girnar hill.

First Peak: After a climb of about 2 miles, there is a Digambar Jain temple and a cave called Rajulmati cave, it is stated that Rajulmati has done penance at this place. There is also a small temple where idol of Bahubali (120 cm) in standing posture is installed. Besides there are footprints of Kundkund. In the temple, the idol of Neminath (Vikram Samvat 1924) is on the main altar. The idols of Parshwanath and Neminath are also there. There is stream called gomukhi ganga and nearby the footprints of 24 tirthanakaras are available.

Second Peak: After 900 steps there are the footprints of Muni Anirudhhkumar and temple of Devi Ambika.

Third Peak: here the footprints of Muni Sambukkumar are installed. Muni has attained nirvana from this place.

Fourth tonk (Peak); Here the footprints of Pradhyman kumar, son of lord krishna are installed here. He attained nirvana from this place.

Fifth tonk; The Fifth tonk is of Lord Neminath's footprints. Lord Neminath, the 22nd tirthankar attained nirvana/moksha from this site.

According to an anecdote said by modern Jain writers, Sajjana, the minister of Chaulukya king Siddharaja Jayasimha, built the Neminatha temple using the state treasury. When he collected the funds to return as a compensation, the king declined to accept it so the funds were used to built the temple. Dhaky concludes that the anecdote is not mentioned in any early work and is false.[15]

Sahastraphana (thousand hooded) Parshwanatha, the image which was consecrated in 1803 CE (VS 1459) by Vijayajinendra Suri, is currently the central deity in the temple. The temple originally housed the golden image of Mahavira and brass images of Shantinatha and Parshwanatha on its sides.[17]

The east facing temple has 52 small shrines surrounding the central temple. It has an open portico with ceilings with fine carvings. In the bhamti or cloisters surrounding the court, there are also some remarkable designs in carved ceilings. The roof of the rangamandapa has fine carvings. The shrine proper must have been removed and replaced with new one at the end of the sixteenth century or the start of the seventeenth century. It is known that Karmachandra Bachchhavat, minister of the king of Bikaner, had sent a funds to renovate temple in Shatrunjaya and Girnar under Jinachandrasuri IV of Kharatara Gaccha during the reign of Akbar. There is a shrine housing replica of Ashtapada hill in the south, shrine with Shatrunjayavatar in west, behind the main temple, and Samet Shikhar (or Nandishwar Dwipa) in north.[14][18]

Girnar's Initial trek

The base of the mountain, known as Girnar Taleti, is about 4 km east of the center of Junagadh. There are temples and other sacred places all along this stretch.[27]

The traveller, in order to reach Girnar Taleti from Junagadh city, will pass through the Wagheshwari or Vagheshwari Gate [Girnar Darwaza], which is close to the Uparkot fort area, Easterly.

At about 200 metres from the gate, to the right of the road, is the Temple of Wagheshwari (Upale Vagheshwari maa), which is joined to the road by a causeway about 150 yards long. An ancient Verai Mata mandir and a modern Gayatri Shakti Peeth mandir are nearby.

About a furlong beyond this is a stone bridge, and just beyond it on the right are the Ashoka's Major Rock Edicts.[10] The edicts are inscribed high up on a large, domed mass of black granite measuring roughly 20 feet x 30 feet. The inscription is in Brahmi script.[2] On the same rock can be found an inscription of the Western Satrap ruler Rudradaman, the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman.

On leaving Ashoka's edicts, the route crosses the handsome bridge over the Sona-rekha, which here forms a fine sheet of water over golden sand, then passes a number of temples, at first on the left bank of the river and then on the right, to the largest of the temples. This is dedicated to Damodar, a name of Krishna, from Dam, a rope, because by tradition his mother in vain attempted to confine him with a rope when a child. The reservoir, Damodar Kund, at this place is accounted very sacred.[10]

Next is an old shrine of Bhavnath, a form of Shiva, close to Girnar Taleti; Mrigi kund and Sudharshan lake are nearby.

Most persons who are not active climbers will probably proceed up the mountain in a swing doli from Taleti. A long ridge runs up from the west, and culminates in a rugged scarped rock, on the top of which are the temples. Close to the old shrine is a well called the Chadani vav.[10]

The paved way begins just beyond this and continues for two-thirds of the ascent. The first resthouse, Chadia Parab, is reached, 480 feet, above the plain; and the second halting-place at Dholi-deri, 1000 feet above the plain. From here the ascent becomes more difficult, winding under the face of the precipice to the third resthouse, 1400 feet up. The path turns to the right along the edge of a precipice, which is very narrow, so that the doli almost grazes the scarp, which rises perpendicularly 200 feet above the traveller. On the right is seen the lofty mountain of Datar, covered with low jungle. At about 1500 feet there is a stone dharmsala, and from this there is a fine view of the rock called the Bhairav-Thampa, "the terrific leap," because devotees used to cast themselves from its top, falling 1000 feet or more.[10]

At 2370 feet above Junagadh the gate of the enclosure known as the Deva Kota, or Ra Khengar's Palace, is reached.[10]

Further trek

.jpg)

South of this, is the Gaumukhi Shrine, near a plentiful spring of water.[10]

From it the crest of the mountain (3330 feet) is reached by a steep flight of stairs. Here is an ancient temple of Amba Mata, which is much resorted to by newly married couples . The bride and bridegroom have their clothes tied together, and attended by their male and female relations, adore the goddess and present cocoa-nuts and other offerings. This pilgrimage is supposed to procure for the couple along continuance of wedded bliss.[10]

Festivals

The main event for Hindus is the Maha Shivaratri fair held every year on the 14th day of the Hindu calendar month of Magha. At least 1 million pilgrims visit the fair to participate in pooja and parikrama of Girnar hill. The procession begins at Bhavnath Mahadev Temple at Bhavnath. It then proceeds onwards to various akharas of various sects of sadhus, which are in Girnar hill from ancient times. The procession of sadhus and pilgrims ends again at Bhavnath temple after visiting Madhi, Malavela and Bara Devi temple. The fair begins with hoisting of fifty-two Gaja long flags at Bhavnath Mahadev temple. This fair is the backbone of the economy of Junagadh, as more than ten lakh pilgrims who visit the fair generate a revenue of 250 million in only five days.[28][29][30]

Religious disputes

The dispute regarding illegal construction around a shrine on the fifth tonk (peak) of Girnar mountain in Junagadh had landed before the Gujarat high court. A trust of the Digambar Jain sect had alleged illegal construction around the idol and charan (footprint) of Neminatha, in a manner that devotees could not see and worship the idol and footprint at the site.[31]

A controversy over ownership of a religious site on Girnar in Junagadh town saw a Hindu sadhu allegedly stabbing a Jain monk.[32] Police sources said victim Muni Shree Prabal Sagarji Maharaj of Udaipur in Rajasthan was taken to a private hospital for the treatment as he had received serious injuries on chest and abdomen. Accused Muktanand Giri was arrested by the police after a case was registered against him at Junagadh taluka police station.[32] Giri stabbed Prabal Sagarji with a knife when the latter arrived at Kamalkund.[32] The dispute over the engraved stone idol and footprint on the fifth peak of Girnar goes back several years.[31] “We have raised the issue about construction of concrete platform and grill in such a manner that Jains cannot see and offer prayer to the footprint of Neminath,” said HR Prajapati, counsel for petitioner Bharatvarshiya Digambar Jain Trith Kshetra Committee.[31] There was a clear high court order in 2005 that prohibited any new construction at the site but it was constructed by overlooking the order,” the counsel said. The archaeological department had concluded that illegal construction had taken place at the site. The matter of illegal construction around the monument had come before the Gujarat high court in 2004. After hearing all parties, the high court in 2005 had directed the Hindu Mahants to not undertake further illegal construction at the site.

It is claimed by Hindus that many images of Hindu gods and goddesses have been replaced by Jains from the Raa Khengar Mahal, ruins of an ancient palace, with carved images of Jain gods, to give an impression that Girnar is essentially a Jain place of pilgrimage.[33] However, these claims seems to be absurd as the main temple of lord Neminatha is made out of a single rock and the temple and idols both are ancient and have mentions in Shatrunjay Mahatmya and similar ancient texts.

The matter of illegal construction around the monument had come before the Gujarat high court in 2004. After hearing all parties, the high court in 2005 had directed the Hindu Mahants to not undertake further illegal construction at the site.[31]

Gallery

lord Neminath temple

lord Neminath temple Samprati Raja temple

Samprati Raja temple Temple view From About 3100 feet at Mt. Girnar

Temple view From About 3100 feet at Mt. Girnar Ambika Mata temple

Ambika Mata temple Chaumukhji Temple

Chaumukhji Temple Vastupala Vihara

Vastupala Vihara Inscription of the Vastupala-vihara on Mount Girnar

Inscription of the Vastupala-vihara on Mount Girnar 1876 image of Vastupala Vihara Jain temple on Girnar

1876 image of Vastupala Vihara Jain temple on Girnar.jpg) King Samprati's Tunk

King Samprati's Tunk

See also

References

- "Girnar | District Junagadh, Government of Gujarat | India". Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Keay, John (2000). India, a History. New York, United States: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-00-638784-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Structure Covering Ashoka's Edicts Collapses in Gujarat". https://www.outlookindia.com/. Retrieved 23 July 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - "Roof over Ashoka rock edicts in Junagadh crashes". The Times of India. 19 July 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Pioneer, The. "Heritage building caves in but Ashoka's edicts as steady as rock". The Pioneer. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Parliament Museum, New Delhi, India - Official website - Rock Edicts". parliamentmuseum.org. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 3.

- Murray 1911, p. 155-157.

- Burgess 1876, p. 166.

- Murray, John (1911). "A handbook for travellers in India, Burma, and Ceylon". Internet Archive. pp. 155–157. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- M A Dhaky, Jitendra B Shah, સાહિત્ય શિલ્પ અને સ્થાપત્યમાં ગીરનાર, L D Indology, 2010

- Dhaky 2010, p. 102.

- Burgess 1876, p. 167.

- Burgess 1876, p. 168.

- Dhaky 2010, p. 134.

- Dhaky 2010, p. 103.

- Dhaky 2010, pp. 134-135.

- Dhaky 2010, p. 135-137.

- Dhaky 2010, p. 103, 123.

- Dhaky 2010, pp. 146-150.

- Burgess 1876, p. 169.

- Burgess 1876, p. 170.

- Dhaky 2010, pp. 102-103.

- Dhaky 2010, p. 89.

- Burgess 1876, pp. 173-74.

- Burgess 1876, p. 174.

- "Mt. Girnar, Pilgrimage Centre, Junagadh, Tourism Hubs, Gujarat, India". gujarattourism.com. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "બાવન ગજની ધ્વજાનાં આરોહણ સાથે આજથી મહાશિવરાત્રિ મેળો Shivaratri fair begins today with hoisting of 52 gaja dwaja". Sandesh. 16 February 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "ગિરનાર ઃ લીલી પરિક્રમા ઃ પરકમ્મા Girnar - Lili Parikrama". Gujarat Samachar. 4 August 2012. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- "જૂનાગઢની આર્થિક કરોડરજજુ શિવરાત્રિનો મેળો : પાંચ દિવસમાં રૂ.રપ કરોડનો લાભ Junagadh's economic backbone - Girnar Shivaratri fair - generates income of 25 crores in five days". Sandesh. 18 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- Correspondent, DNA (10 January 2013). "Jain trust files plea in HC over Girnar shrine row". DNA India. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Jan 3, TNN | Updated; 2013; Ist, 12:23. "Sadhu assaults monk on Mt Girnar | Rajkot News - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Conflict between Hindus, Jains over sacred sites on Mount Girnar mounts

| Edicts of Ashoka (Ruled 269–232 BCE) | |||||

| Regnal years of Ashoka |

Type of Edict (and location of the inscriptions) |

Geographical location | |||

| Year 8 | End of the Kalinga war and conversion to the "Dharma" |  Udegolam Nittur Brahmagiri Jatinga Rajula Mandagiri Yerragudi Sasaram Barabar Kandahar (Greek and Aramaic) Kandahar Khalsi Ai Khanoum (Greek city) | |||

| Year 10[1] | Minor Rock Edicts | Related events: Visit to the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya Construction of the Mahabodhi Temple and Diamond throne in Bodh Gaya Predication throughout India. Dissenssions in the Sangha Third Buddhist Council In Indian language: Sohgaura inscription Erection of the Pillars of Ashoka | |||

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (in Greek and Aramaic, Kandahar) | |||||

| Minor Rock Edicts in Aramaic: Laghman Inscription, Taxila inscription | |||||

| Year 11 and later | Minor Rock Edicts (n°1, n°2 and n°3) (Panguraria, Maski, Palkigundu and Gavimath, Bahapur/Srinivaspuri, Bairat, Ahraura, Gujarra, Sasaram, Rajula Mandagiri, Yerragudi, Udegolam, Nittur, Brahmagiri, Siddapur, Jatinga-Rameshwara) | ||||

| Year 12 and later[1] | Barabar Caves inscriptions | Major Rock Edicts | |||

| Minor Pillar Edicts | Major Rock Edicts in Greek: Edicts n°12-13 (Kandahar) Major Rock Edicts in Indian language: Edicts No.1 ~ No.14 (in Kharoshthi script: Shahbazgarhi, Mansehra Edicts (in Brahmi script: Kalsi, Girnar, Sopara, Sannati, Yerragudi, Delhi Edicts) Major Rock Edicts 1-10, 14, Separate Edicts 1&2: (Dhauli, Jaugada) | ||||

| Schism Edict, Queen's Edict (Sarnath Sanchi Allahabad) Lumbini inscription, Nigali Sagar inscription | |||||

| Year 26, 27 and later[1] |

Major Pillar Edicts | ||||

| In Indian language: Major Pillar Edicts No.1 ~ No.7 (Allahabad pillar Delhi pillar Topra Kalan Rampurva Lauria Nandangarh Lauriya-Araraj Amaravati) Derived inscriptions in Aramaic, on rock: | |||||

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Girnar |