Kosambi

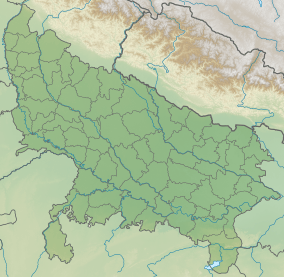

Kosambi (Pali) or Kaushambi (Sanskrit) was an important city in ancient India. It was the capital of the Vatsa kingdom, one of the sixteen mahajanapadas. It was located on the Yamuna River about 56 kilometres (35 mi) southwest of its confluence with the Ganges at Prayaga (modern Prayagraj).

Kosambi | |

|---|---|

city | |

Kosambi cast copper coin. 1st century BCE. Inscribed 𑀓𑁄𑀲𑀩𑀺 Kosabi in the Brahmi script at the top. British Museum. | |

| |

| Coordinates: 25.338984°N 81.392899°E | |

| Country | India |

History

.jpg)

Kosambi was one of the greatest cities in India from the late Vedic period until the end of Maurya Empire with occupation continuing until the Gupta Empire. As a small town, it was established in the late Vedic period,[1][2] by the rulers of Kuru Kingdom as their new capital. The initial Kuru capital Hastinapur was destroyed by floods, and the Kuru King transferred his entire capital with the subjects to a new capital that he built near the Ganga-Jamuma confluence, which was 56 km away from the southernmost part of the Kuru Kingdom now as Prayagraj previously called Allahabad.[3]

During the period prior the Maurya Empire, Kosambi was the capital of the independent kingdom of Vatsa,[4] one of the Mahajanapadas. Kosambi was a very prosperous city by the time of Gautama Buddha, where a large number of wealthy merchants resided. It was an important entrepôt of goods and passengers from north-west and south. It figures very prominently in the accounts of the life of Buddha.

The excavations of the archaeological site of Kosambi was done by G. R. Sharma of Allahabad University in 1949 and again in 1951–1956 after it was authorized by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in March 1948.[5] Excavations have suggested that the site may have been occupied as early as the 12th century BCE. Its strategic geographical location helped it emerge as an important trading center. According to James Heitzman, a large rampart of piled mud was constructed in the 7th to 5th centuries BCE, and was subsequently strengthened by brick walls and bastions, with numerous towers, battlements, and gateways[6] but according to archaeologist G. R. Sharma who led the archaeological excavation of the city, rampart was built and provided with brick revetment between 1025 BC and 955 BC and moat was excavated at the earliest between 855 and 815 BC.[7] Carbon dating of charcoal and Northern Black Polished Ware have historically dated its continued occupation from 390 BC to 600 A.D.[8]

Kosambi was a fortified town with an irregular oblong plan. Excavations of the ruins revealed the existence of gates on three sides-east, west and north. The location of the southern gate can not be precisely determined due to water erosion. Besides the bastions, gates and sub-gates, the city was encircled on three sides by a moat, which, though filled up at places, it still discernible on the northern side. At some points, however, there is evidence of more than one moat. The city extended to an area of approximately 6.5 km. The city shows a large extent of brickworks indicating the density of structures in the city.

The Buddhist commentarial scriptures give two reasons for the name Kausambi/Kosambī. The more favoured[9] is that the city was so called because it was founded in or near the site of the hermitage once occupied by the sage Kusumba (v.l. Kusumbha). Another explanation is[10] that large and stately neem trees or Kosammarukkhā grew in great numbers in and around the city.

Buddhist history of Kosambi

In the time of the Buddha its king was Parantapa, and after him reigned his son Udena (Pali. Sanskrit: Udayana).[11] Kosambī was evidently a city of great importance at the time of the Buddha for we find Ananda mentioning it as one of the places suitable for the Buddha's Parinibbāna.[12] It was also the most important halt for traffic coming to Kosala and Magadha from the south and the west.[13]

The city was thirty leagues by river from Benares (modern day Varanasi). (We are told that the fish which swallowed Bakkula travelled thirty leagues through the Yamunā, from Kosambī to Banares[14]). The usual route from Rājagaha to Kosambī was up the river (this was the route taken by Ananda when he went with five hundred others to inflict the higher punishment on Channa, Vin.ii.290), though there seems to have been a land route passing through Anupiya and Kosambī to Rājagaha[15]). In the Sutta Nipāta (vv.1010-13) the whole route is given from Mahissati to Rājagaha, passing through Kosambī, the halting-places mentioned being: Ujjeni, Gonaddha, Vedisa, Vanasavhya, Kosambī, Sāketa, Sravasthi/Sāvatthi, Setavyā, Kapilavasthu/Kapilavatthu, Kusinārā, Pāvā, Bhoganagara and Vesāli.

Near Kosambī, by the river, was Udayana/Udena's park, the Udakavana, where Ananda and Pindola Bharadvaja preached to the women of Udena's palace on two occasions.[16] The Buddha is mentioned as having once stayed in the Simsapāvana in Kosambī.[17] Mahā Kaccāna lived in a woodland near Kosambī after the holding of the First Buddhist Council.[18]

Buddhist monasteries in Kosambi

Already in the Buddha's time there were four establishments of the Order in Kosambī – the Kukkutārāma, the Ghositārāma, the Pāvārika-ambavana (these being given by three of the most eminent citizens of Kosambī, named respectively, Kukkuta, Ghosita, and Pāvārika), and the Badarikārāma. The Buddha visited Kosambī on several occasions, stopping at one or other of these residences, and several discourses delivered during these visits are recorded in the books. (Thomas, op. cit., 115, n.2, doubts the authenticity of the stories connected with the Buddha's visits to Kosambī, holding that these stories are of later invention).

The Buddha spent his ninth rainy season at Kosambī, and it was on his way there on this occasion that he made a detour to Kammāssadamma and was offered in marriage Māgandiyā, daughter of the Brahmin Māgandiya. The circumstances are narrated in connection with the Māgandiya Sutta. Māgandiyā took the Buddha's refusal as an insult to herself, and, after her marriage to King Udena (of Kosambi), tried in various ways to take revenge on the Buddha, and also on Udena's wife Sāmavatī, who had been the Buddha's follower.[19]

The schism at Kosambi

A great schism once arose among the monks in Kosambī. Some monks charged one of their colleagues with having committed the offence of leaving water in the dipper in the bathroom (which would let mosquitoes breed in it), but he refused to acknowledge the charge and, being himself learned in the Vinaya, argued his case and pleaded that the charge be dismissed. The rules were complicated; on the one hand, the monk had broken a rule and was treated as an offender, but on the other, he should not have been so treated if he could not see that he had done wrong. The monk was eventually excommunicated, and this brought about a great dissension. When the matter was reported to the Buddha, he admonished the partisans of both sides and urged them to give up their differences, but they paid no heed, and even blows were exchanged. The people of Kosambī, becoming angry at the monks' behaviour, the quarrel grew apace. The Buddha once more counselled concord, relating to the monks the story of King Dīghiti of Kosala, but his efforts at reconciliation were of no avail, one of the monks actually asking him to leave them to settle their differences without his interference. In disgust, the Buddha left Kosambī and, journeying through Bālakalonakāragāma and the Pācīnavamsadaya, retired alone to keep retreat in the Pārileyyaka forest. In the meantime the monks of both parties repented, partly owing to the pressure exerted by their lay followers in Kosambī, and, coming to the Buddha at Sāvatthi, they asked his pardon and settled their dispute.[20]

Other legends and references in literature

Bakkula was the son of a banker in Kosambī.[21] In the Buddha's time there lived near the ferry at Kosambī a powerful Nāga-king, the reincarnation of a former ship's captain. The Nāga was converted by Sāgata, who thereby won great fame.[22] Rujā was born in a banker's family in Kosambī.[23] Citta-pandita was also born there.[24] A king, by name Kosambaka, once ruled there.

During the time of the Vajjian heresy, when the Vajjian monks of Vesāli wished to excommunicate Yasa Kākandakaputta, he went by air to Kosambī, and from there sent messengers to the orthodox monks in the different centres (Vin.ii.298; Mhv.iv.17).

It was at Kosambī that the Buddha promulgated a rule forbidding the use of intoxicants by monks (Vin.ii.307).

Kosambī is mentioned in the Buddhist scripture Samyutta Nikāya.[25]

Kausambi Palace architecture

The archaeological excavation conducted by Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) at Kausambi revealed a palace with its foundations going back to 8th century BCE until 2nd century CE and built in six phases. The last phase dated to 1st - 2nd century CE featured an extensive structure which was divided into three blocks and enclosed two galleries. There was a central hall in the central block and presumably used as an audience hall surrounded by rooms which served as a residential place for the ruler. The entire structure was constructed using bricks and stones and two layers of lime were plastered on it. The palace had a vast network of underground chambers and the superstructure and the galleries were made on the principle of true arch. The four-centered pointed arch was used to span narrow passageways and segmental arch for wider areas. The superstructure of central and eastern block was examined to have formed part of a dome that adorned the building. The entire galleries and superstructure were found collapsed under 5 cm thick layer of ash which indicates destruction of the palace through conflagration.[26]

Mauryan Kosambi

Historically, Kosambi remained a strong urban center through the Mauryan period and during the Gupta period. Pillars of Ashoka are found both in Kosambi and in Allahabad. The present location of the Kosambi pillar inside the ruins of the fort attests to the existence of Mauryan military presence in the region. The Allahabad pillar is an edict issued toward the Mahamattas of Kosambi, giving credence to the fact that it was originally located in Kosambi.[27][28]

The schism edict of Kaushambi (Minor Pillar Edict 2) states that, "The King instructs the officials of Kausambi as follows: ..... The way of the Sangha must not be abandoned..... Whosoever shall break the unity of Sangha, whether monk or nun from this time forth, shall be compelled to wear white garments, and to dwell in a place outside the sangha."[29]

All sources cite Kausambi as an important site during the period. More than three thousand stone sculptures have been recovered from Kausambi and its neighbouring ancient sites – Mainhai, Bhita, Mankunwar, and Deoria. These are currently housed in the Prof. G.R. Sharma Memorial Museum of the Department of Ancient History, University of Allahabad, Allahabad Museum and State Museum in Lucknow.

Post-Maurya Kosambi

_damaru_coinage_from_the_Ganges_Valley.jpg)

In the post-Mauryan period a tribal society at Kosambi (modern Allahabad district) made cast copper coinage with and without punchmarks. Their coinage resemble the Damaru-drum. All such coinage has been attributed to the Kosambi. Many Indian museums, such as the National Museum, have these coins in their collections.[30]

It is possible that Pushyamitra Shunga may have shifted his capital from Pataliputra to Kaushambi. After his death, his empire was divided (perhaps amongst his sons), into several Mitra dynasties. The dynasty of Kaushambi also established hegemony over a wide area including Magadha, and possibly Kannauj as well.[31]

Notes

- A. L. Basham (2002). The Wonder That Was India. Rupa and Co. p. 41. ISBN 0-283-99257-3.

- Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2.

- Rohan L. Jayetilleke (5 December 2007). "The Ghositarama of Kaushambi". Daily News. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- J.iv.28; vi.236

- Rohan L. Jayetilleke (5 December 2007). "The Ghositarama of Kaushambi". Daily News. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- James Heitzman, The City in South Asia (Routledge, 2008), pp.13

- Schlingloff, Dieter (1 December 2014). Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study. Anthem Press. ISBN 9781783083497.

- S. Kusumgar and M. G. YadavaMunshi Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi (2002). K. Paddayya (ed.). Recent Studies in Indian Archaeology. pp. 445–451. ISBN 81-215-0929-7.

- E.g., UdA.248; SNA.300; MA.i.535. Epic tradition ascribes the foundation of Kosambī to a Cedi prince, while the origin of the Vatsa people is traced to a king of Kāsī, see PHAI.83, 84

- e.g., MA i.539; PsA.413

- MA.ii.740f; DhA.i.164f

- D.ii.146,169

- See, e.g., Vin.i.277

- AA.i.170; PsA.491

- See Vin.ii.184f

- Vin.ii.290f; SNA.ii.514; J.iv.375

- S.v.437

- PvA.141

- DhA.i.199ff; iii.193ff; iv.1ff; Ud.vii.10

- Vin.i.337-57; J.iii.486ff (cp.iii.211ff); DhA.i.44ff; SA.ii.222f. The story of the Buddha going into the forest is given in Ud.iv.5. and in S.iii.94, but the reason given in these texts is that he found Kosambī uncomfortable owing to the vast number of monks, lay people, and heretics. But see UdA.248f, and SA.ii.222f).

- MA.ii.929; AA.i.170

- AA.i.179; but see J.i.360, where the incident is given as happening at Bhaddavatikā

- J.vi.237f

- J.iv.392

- S.iv.179; but see AA.i.170; MA.ii.929; PsA.491, all of which indicate that the city was on the Yamunā) as being "Gangāya nadiyā tīre." This is either an error, or here the name Gangā refers not to the Ganges but to the Yamunī.

- Gosh, A. (1964). Indian Archaeology: A review 1961-62. New Dehli: Archaeological survey of India. pp. 50–52.

- Romila Thapar (1997). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press, New Delhi. pp. 290–291. ISBN 0-19-564445-X.

- "Krishnaswamy, C.S.; Ghosh, Amalananda (October 1935). "A Note on the Allahabad Pillar of Aśoka". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 4: 697–706". JSTOR 25201233. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vincent Smith (1992). The Edicts of Aśoka. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi. p. 37.

- Sharma, Savita (1981). "Damaru-shaped Coins from Kausambi". Numismatic Digest. 5. Numismatic Society of Bombay. pp. 1–3. OCLC 150424986.

- K. D. Bajpai (October 2004). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. pp. 37–39, 45. ISBN 978-81-7017-035-8.

References

¤ Official website of Kaushambi district

- Early history of Kausambi, IIT Delhi archive

- Entry on Kosambi in the Buddhist Dictionary of Pali Proper Names

- Tripathi, Aruna; The Buddhist Art of Kausambi from 300 BC-AD 550, New Delhi, D.K. Printworld, 2003, ISBN 81-246-0226-3