Latimeria

Latimeria is a rare genus of fish that includes two extant species: West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis). They follow the oldest known living lineage of Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish and tetrapods), which means they are more closely related to lungfish, reptiles and mammals than to the common ray-finned fishes.

| Latimeria | |

|---|---|

| |

| West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae), Natural History Museum of Nantes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | Coelacanthiformes |

| Family: | Latimeriidae |

| Genus: | Latimeria Smith, 1939 |

| Type species | |

| Latimeria chalumnae | |

| Species | |

| |

| |

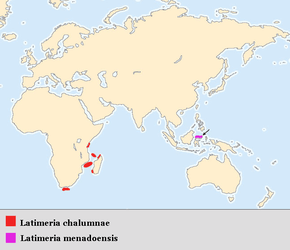

| Range in red and violet | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

They are found along the coastlines of the Indian Ocean and Indonesia.[2][3] Since there are only two species of coelacanth and both are threatened, it is one of the most endangered genus of animals in the world. The West Indian Ocean coelacanth is a critically endangered species.[4]

Biological characteristics

Based on growth rings in the creatures' ear bones (otoliths), scientists infer that individual coelacanths may live as long as 80 to 100 years. Coelacanths live as deep as 700 m (2300 ft) below sea level, but are more commonly found at depths of 90 to 200 m.

Living examples of Latimeria chalumnae have a deep blue color which probably camouflages them from prey species; however, the Indonesian species (L. menadoensis) is brown.

Coelacanth eyes are very sensitive, and have a tapetum lucidum. Coelacanths are almost never caught in the daytime, but have been caught at all phases of the moon. Coelacanth eyes have many rods, receptors in the retina that help animals see in dim light. Together, the rods and tapetum help the fish see better in dark water.

Coelacanths are opportunistic feeders, hunting cuttlefish, squid, snipe eels, small sharks, and other fish found in their deep reef and volcanic slope habitats. Coelacanths are also known to swim head down, backwards or belly up to locate their prey, presumably using their rostral glands.

Scientists suspect that one reason this fish has been so successful is that specimens are able to slow down their metabolisms at will, sinking into the less-inhabited depths and minimizing their nutritional requirements in a sort of hibernation mode.

The coelacanths which live near Sodwana Bay, South Africa, rest in caves at depths of 90 to 150 m during daylight hours, but disperse and swim to depths as shallow as 55 m when hunting at night. The depth is not as important as their need for very dim light and, more importantly, for water which has a temperature of 14 to 22 °C. They will rise or sink to find these conditions. The amount of oxygen their blood can absorb from the water through the gills is dependent on water temperature.

Scientific research suggests the coelacanth must stay in cold, well-oxygenated water or else its blood cannot absorb enough oxygen.[5] The fish seems to be very well adapted to its environment, which is seen as one of the reasons why it has the slowest evolving genome of all known vertebrates.[6]

Reproduction

Female coelacanths give birth to live young, called "pups", in groups of between five and 25 fry at a time; the pups are capable of surviving on their own immediately after birth. Their reproductive behaviors are not well known, but it is believed that they are not sexually mature until after 20 years of age. Gestation time is estimated to be 13 to 15 months.

Discoveries

| Date | Description |

|---|---|

| pre 1938 | Though unknown to the West, the South African natives knew about the fish and called it "gombessa" or "mame."[9] |

| 1938 | (December 23) First discovery of a modern coelacanth 30 kilometers SW of East London, South Africa. |

| 1952 | (December 21) Second specimen known to science identified in the Comoros. Since then more than 200 have been caught off the islands of Grand Comoro and Anjouan. |

| 1988 | First photographs of coelacanths in their natural habitat, by Hans Fricke off Grand Comoro. |

| 1991 | First coelacanth identified near Mozambique, 24 kilometers offshore NE of Quelimane. |

| 1995 | First recorded coelacanth on Madagascar, 30 kilometers S of Tuléar. |

| 1997 | (September 18) New species of coelacanth found in Indonesia. |

| 2000 | A group found by divers off Sodwana Bay, iSimangaliso Wetland Park, South Africa. |

| 2001 | A group found off the coast of Kenya. |

| 2003 | First coelacanth caught by fishermen in Tanzania. Within the year, 22 were caught in total. |

| 2004 | Canadian researcher William Sommers captured the largest recorded specimen of coelacanth off the coast of Madagascar. |

| 2007 | (May 19) Indonesian fisherman Justinus Lahama caught a 1.31 meter (4.30 ft) long, 51 kilogram (112 lb) coelacanth off Sulawesi Island, near Bunaken National Marine Park, that survived for 17 hours in a quarantined pool.[10] |

| 2007 | (July 15) Two fishermen from Zanzibar caught a coelacanth measuring 1.34 meters (4.40 ft), and weighing 27 kilograms (60 lb). The fish was caught off the north tip of the island, off the coast of Tanzania.[11] |

| 2019 | (November 22) Kwa-zulu-Natal south coast. Technical divers video recorded a coelacanth estimated at 1.8 m, 100 kg at a depth of 69n m.[12] |

First find in South Africa

On December 23, 1938, Hendrik Goosen, the captain of the trawler Nerine, returned to the harbour at East London, South Africa, after a trawl between the Chalumna and Ncera Rivers. As he frequently did, he telephoned his friend, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, curator at East London's small museum, to see if she wanted to look over the contents of the catch for anything interesting, and told her of the strange fish he has set aside for her.

Correspondence in the archives of the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB, formerly the JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology) show that Goosen went to great lengths to avoid any damage to this fish and ordered his crew to set it aside for the East London Museum. Goosen later told how the fish was steely blue when first seen, but by the time the 'Nerine' entered East London harbour many hours later, the fish had become dark grey.

Failing to find a description of the creature in any of her books, she attempted to contact her friend, Professor James Leonard Brierley Smith, but he was away for Christmas. Unable to preserve the fish, she reluctantly sent it to a taxidermist. When Smith returned, he immediately recognized it as a type of coelacanth, a group of fish previously known only from fossils. Smith named the new coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae in honor of Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer and the waters in which it was found. The two discoverers received immediate recognition, and the fish became known as a "living fossil". The 1938 coelacanth is still on display in the East London, South Africa, museum.

However, as the specimen had been stuffed, the gills and skeleton were not available for examination, and some doubt therefore remained as to whether it was truly the same species. Smith began a hunt for a second specimen that would take more than a decade.

Comoros

Smith distributed thousands of flyers with a photograph of the fish, description, and reward, but World War II interrupted the search. He also did not know that the 1938 specimen near South Africa was about 1,800 miles (2,900 km) south of its normal habitat.[13] The 100 Pound sterling reward was a very substantial sum to the average subsistence fisherman of the time. Fourteen years later, one specimen was found in the Comoros, but the fish was no stranger to the locals; in the port of Domoni on the Comoran island of Anjouan, the Comorians were puzzled to be so rewarded for a "gombessa" or "mame", their names for the nearly inedible fish that their fishermen occasionally caught by mistake.

The second specimen, found just before Christmas 1952[13] by Comoran fisherman Ahamadi Abdallah, was described as a different species, first as Malania hunti and later as Malania anjounae, after Daniel François Malan, the South African Prime Minister who had dispatched an SAAF Dakota at the behest of Professor Smith to fetch the specimen. It was later discovered that the lack of a first dorsal fin, at first thought to be significant, was caused by an injury early in the specimen's life. Malan was a staunch creationist; when he was first shown the primitive creature, he exclaimed, with a twinkle, "My, it is ugly. Do you mean to say we once looked like that?"[14] The specimen retrieved by Smith is on display at the SAIAB in Grahamstown, South Africa where he worked.

A third specimen was caught in September 1953 and a fourth in January 1954.[13] The Comorans are now aware of the significance of the endangered species, and have established a program to return accidentally-caught coelacanth to deep water.

As for Smith, who died in 1968, his account of the coelacanth story appeared in the book Old Fourlegs, first published in 1956. His book Sea Fishes of the Indian Ocean, illustrated and co-authored by his wife Margaret, remains the standard ichthyological reference for the region.

In 1988, marine biologist Hans Fricke was the first to photograph the species in its natural habitat, 180 metres (590 ft) off Grand Comoro's west coast.[15]

Second species in Indonesia

On September 18, 1997, Arnaz and Mark Erdmann, traveling in Indonesia on their honeymoon, saw a strange fish enter the market at Manado Tua, on the island of Sulawesi.[16] Mark thought it was a gombessa (Comoro coelacanth), although it was brown, not blue. An expert noticed their pictures on the Internet and realized its significance. Subsequently, the Erdmanns contacted local fishermen and asked for any future catches of the fish to be brought to them.

A second Indonesian specimen, 1.2 m in length and weighing 29 kg, was captured alive on July 30, 1998.[8] It lived for six hours, allowing scientists to photographically document its coloration, fin movements and general behavior. The specimen was preserved and donated to the Bogor Zoological Museum, part of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences.[16]

DNA testing revealed this specimen differed genetically from the Comorian population.[17][18] Superficially, the Indonesian coelacanth, locally called raja laut (king of the sea), appears to be the same as those found in the Comoros, except the background coloration of the skin is brownish-gray rather than bluish. This fish was described in a 1999 issue of Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des sciences Paris by Pouyaud et al. It was given the scientific name Latimeria menadoensis.[19] A recent molecular study estimated the divergence time between the two coelacanth species to be 40–30 mya.[20]

On May 19, 2007, Justinus Lahama, an Indonesian fisherman, caught a 1.3-metre-long, 50 kg/110 pound coelacanth off the coast near Manado, on northern Sulawesi Island near Bunaken National Marine Park. After spending 30 minutes out of water, the fish, still alive, was placed in a netted pool in front of a restaurant at the edge of the sea. It survived for 17 hours. Coelacanths usually live at depths of 200-1,000 metres. The fish was filmed by local authorities swimming in the metre-deep pool, then frozen after it died. AFP claim French, Japanese and Indonesian scientists working with the French Institute for Development and Research carried out a necropsy on the coelacanth with genetic analysis to follow. The local university is now studying the carcass.[10][21]

iSimangaliso Wetland Park in South Africa

In South Africa, the search continued on and off over the years. A 46-year-old diver, Rehan Bouwer, lost his life searching for coelacanths in June 1998.

On 28 October 2000, just south of the Mozambique border in Sodwana Bay in the St. Lucia Marine Protected Area, three deep-water divers, Pieter Venter, Peter Timm, and Etienne le Roux, made a dive to 104 metres and unexpectedly spotted a coelacanth.

Calling themselves "SA Coelacanth Expedition 2000", the group returned with photographic equipment and several additional members. On 27 November, after an unsuccessful initial dive the previous day, four members of the group, Pieter Venter, Gilbert Gunn, Christo Serfontein, and Dennis Harding, found three coelacanths. The largest was between 1.5 and 1.8 metres in length; the other two were from 1.0 to 1.2 metres. The fish swam head-down and appeared to be feeding from the cavern ledges. The group returned with video footage and photographs of the coelacanths.

During the dive, however, Serfontein lost consciousness, and 34-year-old Dennis Harding rose to the surface with him in an uncontrolled ascent. Harding complained of neck pains and died from a cerebral embolism while on the boat. Serfontein recovered after being taken underwater for decompression sickness treatment.

In March–April 2002, the Jago Submersible and Fricke Dive Team descended into the depths off Sodwana and observed 15 coelacanths. A dart probe was used to collect tissue samples.

Tanzania

Coelacanths have been caught off the coast of Tanzania since 2004. Two coelacanths were initially reported captured off Songo Mnara, a small island off the edge of the Indian Ocean in August 2003. A spate of 19 more specimens of these extremely rare fishes weighing between 25 and 80 kg were reported netted in the space of the next five months, with another specimen captured in January 2005. A coelacanth weighing as much as 110 kg was reported by the Observer newspaper in 2006.

Officials of the Tanga Coastal Zone Conservation and Development Programme, which has a long-term strategy for protecting the species, see a connection with the timing of the captures with trawling - especially by Japanese vessels - near the coelacanth's habitat, as within a couple of days of trawlers casting their nets, coelacanths have turned up in deep-water gill nets intended for sharks. The sudden appearance of the coelacanths off Tanzania has raised real worries about its future due to damage done to the coelacanth population by the effects of indiscriminate trawling methods and habitat damage.[22]

Hassan Kolombo, a programme co-ordinator, said, "Once we do not have trawlers, we don't get the coelacanths, it's as simple as that." His colleague, Solomon Makoloweka, said they had been pressuring the Tanzanian government to limit trawlers' activities. He said, "I suppose we should be grateful to these trawlers, because they have revealed this amazing and unique fish population. But we are concerned they could destroy these precious things. We want the government to limit their activity and to help fund a proper research program so that we can learn more about the coelacanths and protect them."[22]

In a March 2008 report,[23] the Tanzania Natural Resource Forum, a local environmental nongovernmental organization, warned that a proposed port project at Mwambani Bay could threaten a coastal population of coelacanth.[24]

References

- "Part 7- Vertebrates". Collection of genus-group names in a systematic arrangement. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Holder, Mark T.; Erdmann, Mark V.; Wilcox, Thomas P.; Caldwell, Roy L.; Hillis, David M. (1999). "Two Living Species of Coelacanths?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (22): 12616–20. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612616H. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.22.12616. JSTOR 49396. PMC 23015. PMID 10535971.

- Butler, Carolyn (March 2011). "Living Fossil Fish". National Geographic: 86–93.

- Musick, J. A. (2000). "Latimeria chalumnae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T11375A3274618. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T11375A3274618.en.

- page 200, Weinberg, Samantha. 2006. A Fish Caught in Time: the Search for the Coelacanth. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY.

- "Genome size, GC percentage and 5mC level in the Indonesian coelacanth Latimeria menadoensis". Science Direct. September 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-25031-7

- Rumor or Reality: The Creatures of Cryptozoology, #7 in the list. Livescience.com

- Reuters (2007), "Indonesian fisherman nets ancient fish", Reuters UK, 2007-05-21, Retrieved on 2007-07-16.

- Reuters (2007), "Zanzibar fishermen land ancient fish", Reuters UK, 2007-07-15, Retrieved on 2009-12-13.

- Fraser, Michael D.; Henderson, Bruce A.S.; Carstens, Pieter B.; Fraser, Alan D.; Henderson, Benjamin S.; Dukes, Marc D.; Bruton, Michael N. (26 March 2020). "Live coelacanth discovered off the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast, South Africa". South African Journal of Science. 116 (3/4 March/April 2020). doi:10.17159/sajs.2020/7806.

- Ley, Willy (October 1965). "Fifteen Years of Galaxy — Thirteen Years of F.Y.I." For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 84–94.

- page 73, Weinberg, Samantha. 2006. A Fish Caught in Time: the Search for the Coelacanth. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY.

- Fricke, Hans (June 1988). "Coelacanths:The fish that time forgot". National Geographic. 173 (6): 824–828.

- Jewett, Susan L., "On the Trail of the Coelacanth, a Living Fossil", The Washington Post, 1998-11-11, Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- Erdmann, Mark V. (April 1999). "An Account of the First Living Coelacanth known to Scientists from Indonesian Waters". Environmental Biology of Fishes. Springer Netherlands. 54 (#4): 439–443. doi:10.1023/A:1007584227315. 0378-1909 (Print) 1573-5133 (Online).

- Holder, Mark T.; Mark V. Erdmann; Thomas P. Wilcox; Roy L. Caldwell & David M. Hillis (1999). "Two living species of coelacanths?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (22): 12616–12620. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612616H. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.22.12616. PMC 23015. PMID 10535971.

- Pouyaud, L.; S. Wirjoatmodjo; I. Rachmatika; A. Tjakrawidjaja; R. Hadiaty & W. Hadie (1999). "Une nouvelle espèce de coelacanthe: preuves génétiques et morphologiques". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série III. 322 (4): 261–267. Bibcode:1999CRASG.322..261P. doi:10.1016/S0764-4469(99)80061-4. PMID 10216801.

- Inoue J. G.; M. Miya; B. Venkatesh; M. Nishida (2005). "The mitochondrial genome of Indonesian coelacanth Latimeria menadoensis (Sarcopterygii: Coelacanthiformes) and divergence time estimation between the two coelacanths". Gene. 349: 227–235. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.01.008. PMID 15777665.

- "Ancient Indonesian fish is 'living fossil'" Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, Cosmos Online, 2007-07-29.

- "Dinosaur fish pushed to the brink by deep-sea trawlers", The Observer, 2006-01-08, Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- "Does Tanga need a new harbour at Mwambani Bay?", Tanzania Natural Resource Forum, 2008-03-05, Retrieved on 2009-02-25.

- "Population of prehistoric deep-ocean coelacanth may go the way of the dinosaurs", mongabay.com, 2009-02-25, Retrieved on 2009-02-25.