Lashkar-e-Taiba

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT, Urdu: لشکر طیبہ [ˈləʃkər eː ˈt̪ɛːjbaː]; literally Army of the Good, translated as Army of the Righteous, or Army of the Pure and alternatively spelled as Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, Lashkar-e-Toiba; Lashkar-i-Taiba; Lashkar-i-Tayyeba)[5][6][7] is one of the largest Islamist militant organizations in South Asia.[8] It was founded in 1987 by Hafiz Saeed, Abdullah Azzam and Zafar Iqbal[9][10][11][12] with funding from Osama bin Laden.[13][14]

| Lashkar-e-Taiba لشکر طیبہ | |

|---|---|

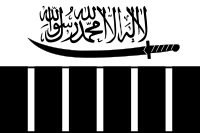

Flag of Lashkar-e-taiba | |

| Ideology | Sunni Islam Islamic fundamentalism |

| Political position | Far-right[1][2] |

| Motive(s) | Integration of Jammu and Kashmir with Pakistan[3] |

| Leader | Hafiz Muhammad Saeed |

| Headquarters | Muridke, Pakistan |

| Area of operations | India and Pakistan[3] |

| Size | 100 000s members all over Pakistan (2005)[4] |

| Allies | Non-State allies |

| Opponent(s) | State opponents |

Lashkar-e-Taiba has been accused by India of attacking military and civilian targets in India, most notably the 2001 Indian Parliament attack, the 2008 Mumbai attacks and the 2019 Pulwama attack on Armed Forces.[15] Its stated objective is to merge whole Kashmir with Pakistan .[16][17] The organization is banned as a terrorist organisation by Pakistan, India,[18] the United States,[19] the United Kingdom,[20] the European Union,[21] Russia, Australia,[22] and the United Nations (under the UNSC Resolution 1267 Al-Qaeda Sanctions List).[23] Though formally banned by Pakistan,[24][25] the general view of India and some Western analysts, including of experts such as former French investigating magistrate Jean-Louis Bruguière and New America Foundation president Steve Coll, is that Pakistan's main intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), continues to give LeT help and protection.[26][27] The Indian government's view is that Pakistan, particularly through its intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence, has both supported the group and sheltered Hafiz Saeed, the group's leader.[28]

Whilst LeT remains banned in Pakistan, the political arm of the group, Jamat ud Dawah (JuD) has also remained banned for spans of time.[24][25][29] However the group still activates in Pakistan.

Objectives

While the primary area of operations of LeT's militant activities is the Kashmir Valley, their professed goal is not limited to challenging India's sovereignty over Jammu and Kashmir.

LeT sees the issue of Kashmir as part of a wider global struggle.[30] The group has adopted maximalist agenda of global jihad though its operations have so far been limited to Kashmir. The group justifies its ideology on verse 2:216 of the Quran. Extrapolating from this verse, the group asserts that military jihad is a religious obligation of all Muslims and defines the many circumstances under which it must be carried out. In a pamphlet entitled "Why Are We Waging Jihad?", the group states that all of India along with many other countries were once ruled by Muslims and were Muslim lands, which is their duty to take it back from the non-Muslims. It declared United States, India, and Israel as "existential enemies of Islam".[31][32] LeT believes that jihad is the duty of all Muslims and must be waged until eight objectives are met: Establishing Islam as the dominant way of life in the world, forcing disbelievers to pay jizya (a tax on non-Muslims), fighting for the weak and feeble against oppressors, exacting revenge for killed Muslims, punishing enemies for violating oaths and treaties, defending all Muslim states, and recapturing occupied Muslim territory. The group construes lands once ruled by Muslims as Muslim lands and considers it as their duty to get them back. It embraces a pan-Islamist rationale for military action.[33][31]

Although it views Pakistan's ruling powers as hypocrites, it doesn't support revolutionary jihad at home because the struggle in Pakistan "is not a struggle between Islam and disbelief". The pamphlet "Why do we do Jihad?" states, "If we declare war against those who have professed Faith, we cannot do war with those who haven’t." The group instead seeks reform through dawa. It aims to bring Pakistanis to LeT's interpretation of Ahl-e-Hadith Islam and thus, transforming the society in which they live.[33]

LeT's leaders have argued that Indian-administered Kashmir was the closest occupied land, and observed that the ratio of occupying forces to the population there was one of the highest in the world, meaning this was among the most substantial occupations of Muslim land. Thus, LeT cadres could volunteer to fight on other fronts but were obligated to fight in Indian-administered Kashmir.[33]

The group was also said to be motivated by the 1992 demolition of the Babri Mosque by Hindu nationalists, for attacks directed against India.[34]

In the wake of the November 2008 Mumbai attacks, investigations of computer and email accounts revealed a list of 320 locations worldwide deemed as possible targets for attack. Analysts believed that the list was a statement of intent rather than a list of locations where LeT cells had been established and were ready to strike.[35]

In January 2009, LeT publicly declared that it would pursue a peaceful resolution in the Kashmir issue and that it did not have global jihadist aims, but the group is still believed to be active in several other spheres of anti-Indian terrorism.[36] The disclosures of Abu Jundal, who was extradited to India by the Saudi Arabian government, however, revealed that LeT is planning to revive militancy in Jammu and Kashmir and conduct major terror strikes in India.

Leadership

- Hafiz Muhammad Saeed – founder of LeT and aamir of its political arm, JuD.[37] Shortly after the 2008 Mumbai attacks Saeed denied any links between the two groups: "No Lashkar-e-Taiba man is in Jamaat-ud-Dawa and I have never been a chief of Lashkar-e-Taiba." On 25 June 2014, the United States declared JuD an affiliate of LeT.[38]

- Abdul Rehman Makki – living in Pakistan – second in command of LeT. He is the brother-in-law of Hafiz Muhammad Saeed.[39] The US has offered a reward of $2 million for information leading to the location of Makki.[40][41]

- Rashid Mukhtar Rehman– released on bail from custody of Pakistan military[42] – senior member of LeT. Named as one of the masterminds of the 2008 Mumbai attacks.[43][44] On 18 December 2014 (two days after the Peshawar school attack), the Pakistani anti-terrorism court granted Lakhvi bail against payment of surety bonds worth Rs. 500,000.[45]

- Yusuf Muzammil – senior member of LeT and named as a mastermind of the 2008 Mumbai attacks by surviving gunman Ajmal Kasab.[43]

- Zarrar Shah – in Pakistani custody – one of LeT's primary liaisons to the ISI. A US official said that he was a "central character" in the planning behind the 2008 Mumbai attacks.[46] Zarrar Shah has boasted to Pakistani investigators about his role in the attacks.[47]

- Muhammad Ashraf – LeT's top financial officer. Although not directly connected to the Mumbai plot, he was added to the UN list of people that sponsor terrorism after the attacks.[48] However, Geo TV reported that six years earlier Ashraf became seriously ill while in custody and died at Civil Hospital on 11 June 2002.[49]

- Mahmoud Mohamed Ahmed Bahaziq – the leader of LeT in Saudi Arabia and one of its financiers. Although not directly connected to the Mumbai plot, he was added to the UN list of people that sponsor terrorism after the attacks.[48][49]

- Nasr Javed – a Kashmiri senior operative,[50] is on the list of individuals banned from entering the United Kingdom for "engaging in unacceptable behaviour by seeking to foment, justify or glorify terrorist violence in furtherance of particular beliefs."[51]

- Abu Nasir (Srinagar commander)

History

Formation

In 1985, Hafiz Mohammed Saeed and Zafar Iqbal formed the Jamaat-ud-Dawa (Organization for Preaching, or JuD) as a small missionary group dedicated to promoting an Ahl-e-Hadith version of Islam. In the next year, Zaki-ur Rehman Lakvi merged his group of anti-Soviet jihadists with the JuD to form the Markaz-ud Dawa-wal-Irshad (Center for Preaching and Guidance, or MDI). The MDI had 17 founders originally, and notable among them was Abdullah Azzam.

The LeT was formed in Afghanistan's Kunar province in 1990[5] and gained prominence in the early 1990s as a military offshoot of MDI.[52] MDI's primary concerns were dawah and the LeT focused on jihad although the members did not distinguish between the two groups' functions. According to Hafiz Saeed, "Islam propounds both dawa[h] and jihad. Both are equally important and inseparable. Since our life revolves around Islam, therefore both dawa and jihad are essential; we cannot prefer one over the other."[33]

Most of these training camps were located in North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) and many were shifted to Pakistan Administered Kashmir for the sole purpose of training volunteers for the Kashmir Jihad. From 1991 onward, militancy surged in Indian Kashmir, as many Lashkar-e-Taiba volunteers were infiltrated into Indian Kashmir from Pakistan Administered Kashmir with the help of the Pakistan Army and ISI.[53] As of 2010, the degree of control that Pakistani intelligence retains over LeT's operations is not known.

Designation as terrorist group

On 28 March 2001, in Statutory Instrument 2001 No. 1261, British Home Secretary Jack Straw designated the group a Proscribed Terrorist Organization under the Terrorism Act 2000.[54][55]

On 5 December 2001, the group was added to the Terrorist Exclusion List. In a notification dated 26 December 2001, United States Secretary of State Colin Powell, designated Lashkar-e-Taiba a Foreign Terrorist Organization.[5]

Lashkar-e-Taiba was banned in Pakistan on 12 January 2002.[7]

It is banned in India as a designated terrorist group under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

It was listed as a terrorist organization in Australia under the Security Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002 on 11 April 2003 and was re-listed on 11 April 2005 and 31 March 2007.[22][56]

On 2 May 2008, it was placed on the Consolidated List established and maintained by the committee established by the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1267 as an entity associated with al-Qaeda. The report also proscribed Jamaat-ud-Dawa as a front group of the LeT.[57] Bruce Riedel, an expert on terrorism, believes that LeT with the support of its Pakistani backers is more dangerous than al-Qaeda.[58]

Aftermath of Mumbai attacks

According to a media report, the US accused JuD of being the front group for the prime suspects of the November 2008 Mumbai attacks, the Lashkar-e-Taiba, the organization that trained the 10 gunmen involved in these attacks.[59]

On 7 December 2008, under pressure from the US and India, Pakistani army launched an operation against LeT and raided a markaz (center) of the LeT at Shawai Nullah, 5 km from Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-controlled Pakistan Administered Kashmir. The army arrested more than twenty members of the LeT including Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, the alleged mastermind of the Mumbai attacks. They are said to have sealed off the center, which included a madrasah and a mosque alongside offices of the LeT according to the government of Pakistan.[60]

On 10 December 2008, India formally requested the United Nations Security Council to designate JuD as a terrorist organization. Subsequently, Pakistan's ambassador to the United Nations Abdullah Hussain gave an undertaking, saying,[61]

After the designation of Jamaat-ud-Dawah (JUD) under (resolution) 1267, the government on receiving communication from the Security Council shall proscribe the JUD and take other consequential actions, as required, including the freezing of assets.

A similar assurance was given by Pakistan in 2002 when it clamped down on the LeT; however, the LeT was covertly allowed to function under the guise of the JuD. While arrests have been made, the Pakistani government has categorically refused to allow any foreign investigators access to Hafiz Muhammad Saeed.

On 11 December 2008, the United Nations Security Council imposed sanctions on JuD, declaring it a global terrorist group. Saeed, the chief of JuD, declared that his group would challenge the sanctions imposed on it in all forums. Pakistan's government also banned the JuD on the same day and issued an order to seal the JuD in all four provinces, as well as Pakistan-controlled Kashmir.[62] Before the ban JuD, ran a weekly newspaper named Ghazwah, two monthly magazines called Majalla Tud Dawaa and Zarb e Taiba, and a fortnightly magazine for children, Nanhe Mujahid. The publications have since been banned by the Pakistani government. In addition to the prohibition of JuD's print publications, the organization's websites were also shut down by the Pakistani government.

After the UNSC ban, Hindu minority groups in Pakistan came out in support of JuD. At protest marches in Hyderabad, Hindu groups said that JuD does charity work such as setting up water wells in desert regions and providing food to the poor.[63][64] However, according to the BBC, the credibility of the level of support for the protest was questionable as protesters on their way to what they believed was a rally against price rises had been handed signs in support of JuD.[64] The JuD ban has been met with heavy criticism in many Pakistani circles, as JuD was the first to react to the Kashmir earthquake and the Ziarat earthquake. It also ran over 160 schools with thousands of students and provided aid in hospitals as well. JuD disguises terrorist activities by showing fake welfare trusts.[65]

In January 2009, JuD spokesperson, Abdullah Muntazir, stressed that the group did not have global jihadist aspirations and would welcome a peaceful resolution of the Kashmir issue. He also publicly disowned LeT commanders Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi and Zarrar Shah, who have both been accused of being the masterminds behind the Mumbai attacks.[36]

In response to the UN resolution and the government ban, the JuD reorganized itself under the name of Tehreek-e-Tahafuz Qibla Awal (TTQA).[36]

On 25 June 2014, the United States added several of LeT affiliates including Jamaat-ud-Dawa, Al-Anfal Trust, Tehrik-e-Hurmat-e-Rasool, and Tehrik-e-Tahafuz Qibla Awwal to the list of foreign terrorist organizations.[66]

Milli Muslim League

Jamaat-ud-Dawa members on 7 August 2017 announced the creation of a political party called Milli Muslim League. Tabish Qayoum, a JuD activist working as the party spokesman, stated they had filed registration papers for a new party with Pakistan's electoral commission.[67] Later in August, JuD under the banner of the party fielded a candidate for the 2017 by-election of Constituency NA-120. Muhammad Yaqoob Sheikh filed his nomination papers as an independent candidate.[68]

The registration application of the party was rejected by ECP on the 12th of October.[69] Hafiz Saeed announced in December, a few days after release from house arrest on 24 November, that his organization will contest the 2018 elections.[70]

Name Changes

In February 2019, after the Pulwama attack, the Pakistan government placed the ban once again on Jamat-ud-Dawa and its charity organization Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation (FIF).[71] To evade the ban, their names were changed to Al Madina and Aisar Foundation respectively and they continued their work as before.[72]

The Resistance Front

The Resistance Front (TRF) was launched after the revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019.[73] Lashkar-e-Taiba leaders form the core of the TRF.[73][74] TRF has taken responsibility for various attacks in Kashmir in 2020 including the deaths of five Indian Army para commandos .[75][76] In June 2020, Army's XV Corps commander Lt General B S Raju said "There is no organisation called TRF. It is a social media entity which is trying to take credit for anything and everything that is happening within the Valley. It is in the electronic domain."[77]

Activities

The group conducts training camps and humanitarian work. Across Pakistan, the organization runs 16 Islamic institutions, 135 secondary schools, an ambulance service, mobile clinics, blood banks and seminaries according to the South Asia Terrorism Portal.[5]

The group actively carried out attacks on Indian Armed Forces in Jammu and Kashmir.

Some breakaway Lashkar members have been accused of carrying out attacks in Pakistan, particularly in Karachi, to mark its opposition to the policies of former president Pervez Musharraf.[7][78][79]

Publications

Christine Fair estimates that, through its editing house Dar al Andalus, "LeT is perhaps the most prolific producer of jihadi literature in Pakistan." By the end of the 90s, the Urdu monthly magazine Mujallah al-Dawah had a circulation of 100 000, another monthly magazine, Ghazwa, of 20 000, while other weekly and monthly publications target students (Zarb-e-Tayyaba), women (Tayyabaat), children and those who are literate in English (Voice of Islam and Invite) or Arabic (al-Ribat.) It also publishes, every year, around 100 booklets, in many languages.[80] It has been described as a "profitable department, selling lacs of books every year."[81]

Training camps

The LeT training camps are presently located at a number of locations in Pakistan. These camps, which include its base camp, Markaz-e-Taiba in Muridke near Lahore and the one near Manshera, are used to impart training to militants. In these camps, the following trainings are imparted:

- the 21-day religious course (Daura-e-Sufa)[82]

- the 21-day basic combat course (Daura-e-Aam)[83]

- the three-months advanced combat course (Daura-e-Khaas)[83][84]

26/11 mastermind, Zabiuddin Ansari alias, Abu Jundal arrested recently by Indian intelligence agencies is reported to have disclosed that paragliding training was also included in the training curriculum of LeT cadres at is camps in Muzaffarabad.[85]

These camps have long been tolerated since Inception by the Pakistan's powerful Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency because of their usefulness against India and in Afghanistan although they have been instructed not to mount any operations for now.[86] A French anti-terrorism expert, Jean-Louis Bruguière, in his Some Things that I Wasn’t Able to Say has stated that the regular Pakistani army officers trained the militants in the LeT training camps until recently. He reached this conclusion after interrogating a French militant, Willy Brigitte, who had been trained by the LeT and arrested in Australia in 2003.[87][88]

Markaz-e-Taiba

The LeT base camp Markaz-e-Taiba is in Nangal Saday, about 5 km North of Muridke, on East side of G.T. road; about 30 km from Lahore, was established in 1988. It is spread over 200 acres (0.81 km2) of land and contains a madrassa, hospital, market, residences, a fish farm and agricultural tracts. The initial sectarian religious training, Daura-e-Sufa is imparted here to the militants.[82]

Other training camps

In 1987, LeT established two training camps in Afghanistan. The first one was the Muaskar-e-Taiba at Jaji in Paktia Province and the second one was the Muaskar-e-Aqsa in Kunar Province.[89] US intelligence analysts justify the extrajudicial detention of at least one Guantanamo detainee because they allege he attended a LeT training camp in Afghanistan. A memorandum summarizing the factors for and against the continued detention of Bader Al Bakri Al Samiri asserts that he attended a LeT training camp.

Mariam Abou Zahab and Olivier Roy in their Islamist Networks: The Afghan-Pakistan Connection (London: C. Hurst & Co., 2004) mentioned three training camps in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, the principal one is the Umm-al-Qura training camp at Muzaffarabad. Every month five hundred militants are trained in these camps. Muhammad Amir Rana in his A to Z of Jehadi Organizations in Pakistan (Lahore: Mashal, 2004) listed five training camps. Four of them, the Muaskar-e-Taiba, the Muaskar-e-Aqsa, the Muaskar Umm-al-Qura and the Muaskar Abdullah bin Masood are in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and the Markaz Mohammed bin Qasim training camp is in Sanghar District of Sindh. Ten thousand militants had been trained in these camps till 2004.

Funding

The government of Pakistan began to fund the LeT during the early 1990s and by around 1995 the funding had grown considerably. During this time the army and the ISI helped establish the LeT's military structure with the specific intent to use the militant group against India. The LeT also obtained funds through efforts of the MDI's Department of Finance.[33]

Until 2002, the LeT collected funds through public fundraising events usually using charity boxes in shops and mosques. The group also received money through donations at MDI offices, through personal donations collected at public celebrations of an operative's martyrdom, and through its website.[33] The LeT also collected donations from the Pakistani immigrant community in the Persian Gulf and United Kingdom, Islamic Non-Governmental Organizations, and Pakistani and Kashmiri businessmen.[5][33][90] LeT operatives have also been apprehended in India, where they had been obtaining funds from sections of the Muslim community.[91]

Although many of the funds collected went towards legitimate uses, e.g. factories and other businesses, a significant portion was dedicated to military activities. According to US intelligence, the LeT had a military budget of more than $5 million by 2009.[33]

Use of charity aid to fund relief operations

LeT assisted victims after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake.[92] In many instances, they were the first on the scene, arriving before the army or other civilians.[93]

A large amount of funds collected among the Pakistani expatriate community in Britain to aid victims of the earthquake were funneled for the activities of LeT although the donors were unaware. About £5 million were collected, but more than half of the funds were directed towards LeT rather than towards relief efforts. Intelligence officials stated that some of the funds were used to prepare for an attack that would have detonated explosives on board transatlantic airflights.[94] Other investigations also indicated the aid given for earthquake victims was directly involved to expand Lashkar-e-Taiba's activities within India.[95]

Notable incidents

- 1998 Wandhama massacre: 23 Kashmiri pandits were murdered on 25 January 1998.[96]

- In March 2000, Lashkar-e-Taiba militants are claimed to have been involved in the Chittisinghpura massacre, where 35 Sikhs in the town of Chittisinghpura in Kashmir were killed. An 18-year-old male, who was arrested in December of that year, admitted in an interview with a New York Times correspondent to the involvement of the group and expressed no regret in perpetrating the anti-Sikh massacre. In a separate interview with the same correspondent, Hafiz Muhammad Saeed denied knowing the young man and dismissed any possible involvement of LeT.[97][98] In 2010, the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) associate David Headley, who was arrested in connection with the 2008 Mumbai attacks, reportedly confessed to the National Investigation Agency that the LeT carried out the Chittisinghpura massacre.[99] He is said to have identified an LeT militant named Muzzamil as part of the group which carried out the killings apparently to create communal tension just before Clinton's visit.[100]

- The LeT was also held responsible by the government for the 2000 terrorist attack on Red Fort, New Delhi.[101] LeT confirmed its participation in the Red Fort attack.[102]

- LeT claimed responsibility for an attack on the Srinagar Airport that left five Indians and six militants dead.[102]

- The group claimed responsibility for an attack on Indian security forces along the border.[102]

- The Indian government blamed LeT, in coordination with Jaish-e-Mohammed, for a 13 December 2001 assault on parliament in Delhi.[103]

- 2002 Kaluchak massacre 31 killed 14 May 2002. Australian government attributed this massacre to Lashkar-e-Taiba when it designated it as a terrorist organization.

- 2003 Nadimarg Massacre 24 Kashmiri pandits gunned down on the night of 23 March 2003.

- 2005 Delhi bombings: During Diwali, Lashkar-e-Taiba bombed crowded festive Delhi markets killing 60 civilians and maiming 527.[104]

- 2006 Varanasi bombings: Lashkar-e-Taiba was involved in serial blasts in Varanasi in the state of Uttar Pradesh. 37 people died and 89 were seriously injured.[105]

- 2006 Doda massacre 34 Hindus were killed in Kashmir on 30 April 2006.

- 2006 Mumbai train bombings: The investigation launched by Indian forces and US officials have pointed to the involvement of Lashkar-e-Taiba in Mumbai serial blasts on 11 July 2006. The Mumbai serial blasts on 11 July claimed 211 lives and maimed about 407 people and seriously injured another 768.[106]

- On 12 September 2006 the propaganda arm of the Lashkar-e-Taiba issued a fatwa against Pope Benedict XVI demanding that Muslims assassinate him for his controversial statements about Muhammad.[107]

- On 16 September 2006, a top Lashkar-e-Taiba militant, Abu Saad, was killed by the troops of 9-Rashtriya Rifles in Nandi Marg forest in Kulgam. Saad belongs to Lahore in Pakistan and also oversaw LeT operations for the past three years in Gul Gulabhgash as the outfit's area commander. Apart from a large quantity of arms and ammunition, high denomination Indian and Pakistani currencies were also recovered from the slain militant.[108]

- 2008 Mumbai attacks In November 2008, Lashkar-e-Taiba was the primary suspect behind the Mumbai attacks but denied any part.[109] The lone surviving gunman, Ajmal Amir Kasab, captured by Indian authorities admitted the attacks were planned and executed by the organization.[110][111] United States intelligence sources confirmed that their evidence suggested Lashkar-e-Taiba is behind the attacks.[112] A July 2009 report from Pakistani investigators confirmed that LeT was behind the attack.[113]

- On 7 December 2008, under pressure from USA and India, the Pakistan Army launched an operation against LeT and Jamat-ud-Dawa to arrest people suspected of 26/11 Mumbai attacks.[114]

- In August 2009, LeT issued an ultimatum to impose Islamic dress code in all colleges in Jammu and Kashmir, sparking fresh fears in the tense region.[115]

- In September and October 2009, Israeli and Indian intelligence agencies issued alerts warning that LeT was planning to attack Jewish religious places in Pune, India and other locations visited by Western and Israeli tourists in India. The gunmen who attacked the Mumbai headquarters of the Chabad Lubavitch movement during the November 2008 attacks were reportedly instructed that, "Every person you kill where you are is worth 50 of the ones killed elsewhere."[116]

- News sources have reported that members of LeT were planning to attack the U.S. and Indian embassies in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on 26 November 2009, to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the November 2008 Mumbai attacks. At least seven men were arrested in connection to the plot, including a senior member of LeT.[116]

- Two Chicago residents, David Coleman Headley and Tahawwur Hussain Rana, were allegedly working with LeT in planning an attack against the offices and employees of Jyllands-Posten, a Danish newspaper that published controversial cartoons of Muhammad. Indian news sources also implicated the men in the November 2008 Mumbai attacks and in LeT's Fall 2009 plans to attack the U.S. and Indian embassies in Bangladesh.

Losing of LeT Group Heads

- Abrar, Intelligence Chief of LeT in Afghanistan was arrested and 8 other militants were killed by NDS in Nangarhar Province.[117][118]

- Abu Dujana, Chief of Lashkar-e-taiba in Kashmir Valley was killed by Indian security forces on 2 August 2017.[119]

- Abu Qasim, operations commander of the terrorist group, was killed in a joint operation by the Indian army and the special operations group of the Jammu and Kashmir police on 30 October 2015.[120]

- Junaid Mattoo, Lashkar-e-Taiba commander for Kulgam was killed in an encounter with security forces in Arvani.[121]

- Waseem Shah, responsible for recruiting fresh cadres and involved in many attacks on security forces in south Kashmir was killed on 14 October 2017.[122]

- Six top LeT commanders including Owaid, son of Abdul Rehman Makki and nephew of Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, wanted commanders Zargam and Mehmood, were killed on 18 November 2017. Mehmood was responsible for killing a constable on 27 September and two Garud commandos on 11 October.[123]

External relationships

Support from Saudi Arabia

According to a secret December 2009 paper signed by the US secretary of state, "Saudi Arabia remains a critical financial support base for al-Qaeda, the Taliban, LeT and other terrorist groups."[124] LeT used a Saudi-based front company to fund its activities in 2005.[125][126]

Role in India-Pakistan relations

LeT attacks have increased tensions in the already contentious relationship between India and Pakistan. Part of the LeT strategy may be to deflect the attention of Pakistan's military away from the tribal areas and towards its border with India. Attacks in India also aim to exacerbate tensions between India's Hindu and Muslim communities and help LeT recruitment strategies in India.[30]

LeT cadres have also been arrested in different cities of India. On 27 May, a LeT militant was arrested from Hajipur in Gujarat. On 15 August 2001, a LeT militant was arrested from Bhatinda in Punjab.[127] Mumbai police's interrogation of LeT operative, Abu Jundal revealed that LeT has planned 10 more terror attacks across India and he had agreed to participate in these attacks.[128] A top US counter-terrorism official, Daniel Benjamin, in a news conference on 31 July 2012, told that LeT was a threat to the stability in South Asia urging Pakistan to take strong action against the terror outfit.[129] Interrogation of Jundal revealed that LeT was planning to carry out aerial attacks on Indian cities and had trained 150 paragliders for this. He knew of these plans when he visited a huge bungalow in eastern Karachi where top LeT men, supervised by a man called Yakub were planning aerial and sea route attacks on India.[130]

Inter-Services Intelligence involvement

The ISI have provided financial and material support to LeT.[28] In 2010, Interpol issued warrants for the arrest of two serving officers in the Pakistan army for alleged involvement in the 2008 Mumbai attacks.[131] The LeT was also reported to have been directed by the ISI to widen its network in the Jammu region where a considerable section of the populace comprised Punjabis. The LeT has a large number of activists who hail from Indian Punjab and can thus effectively penetrate into Jammu society.[132] A 13 December 2001 news report cited a LeT spokesperson as saying that LeT wanted to avoid a clash with the Pakistani government. He claimed a clash was possible because of the suddenly conflicting interests of the government and of the militant outfits active in Jammu and Kashmir even though the government had been an ardent supporter of Muslim freedom movements, particularly that of Kashmir.

Pakistan denies giving orders to LeT's activities. However, the Indian government and many non-governmental think-tanks allege that the Pakistani ISI is involved with the group.[5] The situation with LeT causes considerable strain in Indo-Pakistani relations, which are already mired in suspicion and mutual distrust.

Role in Afghanistan

The LeT was created to participate in the Mujahideen conflict against the Najibullah regime in Afghanistan. In the process, the outfit developed deep linkages with Afghanistan and has several Afghan nationals in its cadre. The outfit had also cultivated links with the former Taliban regime in Afghanistan and also with Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda network. Even while refraining from openly displaying these links, the LeT office in Muridke was reportedly used as a transit camp for third country recruits heading for Afghanistan.

Guantanamo detainee Khalid Bin Abdullah Mishal Thamer Al Hameydani's Combatant Status Review Tribunal said that he had received training via Lashkar-e-Taiba.[133]

Lashkar-e-Taiba's directed attacks against Indian targets in Afghanistan. Three major attacks occurred against Indian government employees and private workers in Afghanistan.[134]

The Combatant Status Review Tribunals of Taj Mohammed and Rafiq Bin Bashir Bin Jalud Al Hami, and the Administrative Review Board hearing of Abdullah Mujahid and Zia Ul Shah allege that they too were members or former members of Lashkar-e-Taiba.[135][136][137][138]

Links with other militant groups

While the primary focus for the Lashkar is the operations in Indian Kashmir, it has frequently provided support to other international terrorist groups. Primary among these is the al-Qaeda Network in Afghanistan. LeT members also have been reported to have engaged in conflicts in the Philippines, Bosnia, the Middle East and Chechnya.[139] There are also allegations that members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conducted arms transfers and made deals with LeT in the early 1990s.[140]

al-Qaeda

- The Lashkar is claimed to have operated a military camp in post–11 September Afghanistan, and extending support to the ousted Taliban regime. The outfit had claimed that it had assisted the Taliban militia and Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda network in Afghanistan during November and December 2002 in their fight against the US-aided Northern Alliance.[141]

- A leading al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah, who became operational chief of al-Qaeda after the death of Mohammed Atef, was caught in a Lashkar safehouse at Faislabad in Pakistan.[6][142]

- A news report in the aftermath of 11 September attacks in the U.S. has indicated that the outfit provides individuals for the outer circle of bin Laden's personal security.

- Other notable al-Qaeda operatives said to have received instruction and training in LeT camps include David Hicks, Richard Reid and Dhiren Barot.[142]

Jaish-e-Mohammed

News reports, citing security forces, said that the latter suspect that in 13 December 2001 attack on India's Parliament in New Delhi, a joint group from the LeT and the Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) were involved. The attack precipitated the 2001-2002 India-Pakistan standoff.

Hizb-ul-Mujahideen

The Lashkar is reported to have conducted several of its major operations in tandem with the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen.

Ties to attacks in the United States

- The Markaz campus at Muridke in Lahore, its headquarters, was used as a hide-out for both Ramzi Yousef, involved in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, and Mir Aimal Kansi, convicted and executed for the January 1993 killing of two Central Intelligence Agency officers outside the agency's headquarters in Langley, Virginia.[143]

- A group of men dubbed the Virginia Jihad Network attended LeT training camps and were convicted in 2006 of conspiring to provide material support to the LeT.[144] The leader of the group, Ali al-Timimi, urged the men to attend the LeT camps and to "go abroad to join the mujahideen engaged in jihad in Afghanistan." The men also trained with weapons in Virginia.[145]

- Two U.S. citizens, Syed Haris Ahmed and Ehsanul Sadequee were arrested in 2006 for attempting to join LeT. Ahmed traveled to Pakistan in July 2005 to attend a terrorist training camp and join LeT. The men also shot videos of U.S. landmarks in the Washington, D.C. area for potential terrorist attacks. They were convicted in Atlanta during the summer of 2009 for conspiring to provide material support to terrorists.[146]

- U.S. citizen Ahmad Abousamra was indicted in November 2009 for providing material support to terrorists. He allegedly went to Pakistan in 2002 to join the Taliban and LeT, but failed.[147] The F.B.I. issued a $50,000 reward for his capture on 3 October 2012.[148][149][150]

See also

- 2008 Mumbai attacks

- Abdul Rauf Asghar

- Ajmal Kasab

- al Qaeda

- All Parties Hurriyat Conference

- Ansar ul-Mujahideen

- Burhan Wani

- Kashmir conflict and Problems before Plebiscite

- Lascar

- List of designated terrorist groups

- List of organizations banned by the Government of India

- Osama bin Laden

- Rukhsana Kausar

- Syed Ali Shah Geelani

Further reading

- Bacon, Tricia (2019), "Preventing the Next Lashkar-e-Tayyiba Attack", The Washington Quarterly, 42: 53–70, doi:10.1080/0163660X.2019.1594135

References

- "Democracy between military might and the ultra-right in Pakistan". East Asia Forum. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Didier Chaudet (3 July 2012). "L'extrême-droite pakistanaise est-elle une menace pour les Etats-Unis?". Huffington Post (in French). Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- Encyclopedia of Terrorism, pp 212–213, By Harvey W. Kushner, Edition: illustrated, Published by SAGE, 2003, ISBN 0-7619-2408-6, ISBN 978-0-7619-2408-1

- Steve Coll (14 November 2005), "Fault Lines", The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Lashkar-e-Toiba 'Army of the Pure'". South Asia Terrorism Portal. 2001. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- Jayshree Bajoria (14 January 2010). "Profile: Lashkar-e-Taiba (Army of the Pure) (a.k.a. Lashkar e-Tayyiba, Lashkar e-Toiba; Lashkar-i-Taiba)". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- "Profile: Lashkar-e-Toiba". BBC News. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "Mumbai Terror Attacks Fast Facts". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- "Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the Future of Global Jihad". Brookings.edu. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the Future of Global Jihad, transcript" (PDF). Brookings.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "The 9/11 Attacks' Spiritual Father". Brookings.edu. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "The 15 faces of terror". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- E. Atkins, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Worldwide Extremists and Extremist Groups. Greenwood Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0313324857.

- "THE FINANCING OF LASHKAR-E-TAIBA". Global Ecco. June 2018.

- European Foundation for South Asian Studies. "David Coleman Headley: Tinker, Tailor, American, Lashkar-e-Taiba, ISI Spy". www.efsas.org.

- "Who is Lashkar-e-Tayiba". Dawn. 3 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- The evolution of Islamic Terrorism Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine by John Moore, PBS

- "Banned Terrorist Organizations". National Investigation Agency. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- USA redesignates Pakistan-based terror groups Archived 6 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine The Tribune

- "Terrorism Act 2000". Schedule 2, Act No. 11 of 2000. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- "Council Decision of 22 December 2003". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Listed terrorist organizations". Australian National Security. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Sanctions List Materials | United Nations Security Council". Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Arshad, Muhammad (7 November 2011). "JUD not included in revised list". Pakistan Observer. Islamabad. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- "No Coverage of JUD, other proscribed outfits". Pakistan Observer. Islamabad. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- "Steve Coll: "Zawahiri's record suggests he will struggle" | FRONTLINE". PBS. 2 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Cordesman, Anthony H.; Burke, Arleigh A.; Vira, Varun (25 July 2011), Pakistan: Violence vs. Stability, Burke Chair in Strategy, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, pp. 183–184, archived from the original on 12 October 2017, retrieved 9 September 2017

- Atkins, Stephen E. (2004). Encyclopedia of modern worldwide extremists and extremist groups. Greenwood Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-313-32485-7.

- "Pakistan ban Jamat ud dawah and Haqqani network". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015.

-

Rabasa, Angel; Robert D. Blackwill; Peter Chalk; Kim Cragin; C. Christine Fair; Brian A. Jackson; Brian Michael Jenkins; Seth G. Jones; Nathaniel Shestak; Ashley J. Tellis (2009). "The Lessons of Mumbai". The RAND Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Haqqani, Husain (2005). "The Ideologies of South Asian Jihadi Groups" (PDF). Current Trends in Islamist Ideology. Hudson Institute. 1: 12–26. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- Who are the Kashmir militants Archived 28 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 6 April 2005

- Tankel, Stephen (27 April 2011), Lashkar-e-Taiba: Past Operations and Future Prospects (PDF), National Security Studies Program Policy Paper, Washington, DC: New America Foundation, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2011

- Gordon, Sandy; Gordon, A. D. D. (2014). India's Rise as an Asian Power: Nation, Neighborhood, and Region. Georgetown University Press. pp. 54–58. ISBN 9781626160743.

- Ramesh, Randeep (19 February 2009). "Mumbai attackers had hit list of 320 world targets". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- Roul, Animesh (2009). "Pakistan's Lashkar-e-Taiba Chooses Between Kashmir and the Global Jihad". Terrorism Focus. Washington, D.C.: Jamestown Foundation. 6 (3). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- "We didn't attack Mumbai, says Lashkar chief". The Times of India. 5 December 2008. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "US names jud as terror outfit, sanctions 2 let leaders". Patrika Group (in Hindi). Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- Parashar, Sachin (5 April 2012). "Hafiz Saeed's brother-in-law Abdul Rehman Makki is a conduit between Lashkar-e-Taiba and Taliban". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- "Hafiz Abdul Rahman Makki". Articles. Rewards for Justice Website. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Walsh, Declan (3 April 2012). "U.S. Offers $10 Million Reward for Pakistani Militant Tied to Mumbai Attacks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Rondeaux, Candace (9 December 2008). "Pakistan Arrests Suspected Mastermind of Mumbai Attacks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Lakhvi, Yusuf of LeT planned Mumbai attack". Associated Press. 4 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- Buncombe, Andrew (8 December 2008). "'Uncle' named as Mumbai terror conspirator". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- "ATC approves bail of Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi in Mumbai attacks case". Dawn. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Schmitt, Eric (7 December 2008). "Pakistan's Spies Aided Group Tied to Mumbai Siege, Eric Schmitt, et al., NYT, 7 December 2008". The New York Times. Mumbai (India);Pakistan. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Oppel, Richard A. (31 December 2008). "Pakistani Militants Admit Role in Siege, Official Says, Richard Oppel, Jr., NYT, 2008-12-31". The New York Times. India;Pakistan. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Worth, Robert F. (10 December 2008). "Indian Police Name 2 More Men as Trainers and Supervisors of Mumbai Attackers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- "Four Pakistani militants added to UN terrorism sanctions list". UN News Center. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 23 December 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- Slack, James; Boden, Nicola (6 May 2009). "Jacqui Smith's latest disaster: Banned U.S. shock jock never even tried to visit Britain – now he's suing". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- "Home Office name hate promoters excluded from the UK". Press Release. UK Home Office. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

-

Kurth Cronin, Audrey; Huda Aden; Adam Frost; Benjamin Jones (6 February 2004). "Foreign Terrorist Organizations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) -

Ashley J. Tellis (11 March 2010). "Bad Company – Lashkar-e-Tayyiba and the Growing Ambition of Islamist Mujahidein in Pakistan" (PDF). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

The group's earliest operations were focused on the Kunar and Paktia provinces in Afghanistan, where LeT had set up several training camps in support of the jihad against the Soviet occupation.

- "Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards". Parliament of the United Kingdom. 16 January 2002. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "Statutory Instrument 2001 No. 1261: The Terrorism Act 2000 (Proscribed Organizations) (Amendment) Order 2001". legislation.gov.uk. 28 March 2001. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "CRIMINAL CODE AMENDMENT REGULATIONS 2007 (NO. 12) (SLI NO 267 OF 2007)". Austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- UN declares Jamaat-ud-Dawa a terrorist front group Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Long War Journal – 11 December 2008

- "Lashkar-e-Taiba now more dangerous than al Qaeda: US expert". 10 July 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012.

- "Hafiz Saeed rejects US terrorism accusations". Al Jazeera English. 3 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Subramanian, Nirupama (8 December 2008). "Shut down LeT operations, India tells Pakistan". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "Pakistan likely to ban Jamaat-ud-Dawa". The Times of India. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- "Pakistan bans Jamaat-ud-Dawa, shuts offices". The Times of India. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Hamid Shaikh (16 December 2008). "Pakistani Hindus rally to support Islamic charity". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Hindus rally for Muslim charity". BBC. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- "Jamaat chief rejects Indian charges". Al Jazeera. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- "US adds LeT's parent Jama'at-ud-Dawa to list of Terror Organizations". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- Shahzad, Asif (7 August 2017). "Charity run by Hafiz Saeed launches political party in Pakistan". Reuters. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "NA-120 by-polls: JUD fields candidate". 4= The Nation. 13 August 2017. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- "Milli Muslim League registration rejected by ECP". Al Jazeera. 12 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- "Hafiz Saeed-backed MML to contest polls". The Hindu. 4 December 2017.

- "Jamat-ud-Dawa, its charity arm Falah-e-Insaniyat Foundation change name, bypass ban". The Hindu. 24 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Ban not fully enforced". Daily Times. 23 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Gupta, Shishir (8 May 2020). "Pak launches terror's new face in Kashmir, Imran Khan follows up on Twitter". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "'Pakistan trying to securalise Kashmir militancy': Lashkar regroups in Valley as The Resistance Front". The Indian Express. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Gupta, Shishir (8 May 2020). "New J&K terror outfit run by LeT brass: Intel". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Pubby, Manu; Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy (29 April 2020). "The Resistance Front: New name of terror groups in Kashmir". The Economic Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Security Forces Have Eliminated Over 100 Militants in Jammu and Kashmir This Year, Say Officials". CNN News18. 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Indians in Pak ready to work for LeT: Headley Archived 20 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Press Trust of India, 18 June 2011

- Some Karachi-based Indians willing to work with LeT: Headley, Agencies, Sat 18 June 2011

- C. Christine Fair, In Their Own Words: Understanding Lashkar-e-Tayyaba, Oxford University Press (2018), pp. 86–87

- Muḥammad ʻĀmir Rānā & Amir Mir, A to Z of Jehadi Organizations in Pakistan, Mashal Books (2004), p. 327

- Dholabhai, Nishit (28 December 2006). "Lid off Lashkar's Manipur mission". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Swami, Praveen (2 December 2008). "A journey into the Lashkar". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- Raman, B. (15 December 2001). "The Lashkar-e-Toiba (LET)". South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- "Paragliding part of LeT training camp: Jundal". 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- "The trouble with Pakistan by Economist". The Economist. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Pakistani Army ran Muslim extremist training camps: Anti-terrorist expert". Daily News and Analysis. 14 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Bremner, Charles (14 November 2009). "Pakistani Army ran Muslim extremist training camps, says anti-terrorist expert". The Times. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Rao, Aparna, Michael Bollig & Monika Böck. (ed.). (2008) The Practice of War: Production, Reproduction and Communication of Armed Violence, Oxford: Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-84545-280-3, pp.136–7

- Lashkar-e-Taiba Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Federation of American Scientists Intelligence Resource Program

- "Meet the Lashkar-e-Tayiba's fundraiser". Rediff.com. 31 December 2004. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- 7=Kate Clark (5 October 2006). "UN quake aid went to extremists". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- McGirk, Jan (October 2005). "Jihadis in Kashmir: The Politics of an Earthquake". Qantara. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- Partlow, Joshua; Kamran Khan (15 August 2006). "Charity Funds Said to Provide Clues to Alleged Terrorist Plot". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2009.

- Quake came as a boon for Lashkar leadership Archived 3 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu, 17 November 2005

- "Violent 'army of the pure'". BBC. 14 December 2001. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Lashkar militant admits killing Sikhs in Chittisinghpura". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Bearak, Barry (31 December 2000). "A Kashmiri Mystery". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- "Lashkar behind Sikh massacre in Kashmir in 2000, says Headley". The Hindustan Times. 25 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011.

- Chittisinghpura Massacre: Obama’s proposed visit makes survivors recall tragedy Archived 16 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Tribune, Chandigarh. 25 October 2010.

- Red Fort attackers’ accomplice shot Archived 26 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine,The Tribune

- "Q+A – Who is Pakistan's Hafiz Mohammad Saeed?". Reuters. 6 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- Prashant, Pandey (17 December 2001). "Jaish, Lashkar carried out attack with ISI guidance: police". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- "Delhi Metro was in LeT's cross-hairs". Rediff.com. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Lashkar behind blasts: UP official". Rediff.com. 9 March 2006. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "350 rounded up in Maharashtra". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- Raman, B. (2 October 2006). "LeT Issues Fatwa to Kill the Pope (Paper no. 1974)". South Asia Analysis Group (SAAG). Archived from the original on 12 October 2006.

- "Top Lashkar-e-Taiba militant killed". NDTV. 16 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- "Chaos reigns throughout Bombay". Le Monde (in French). 27 November 2008. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- "Three Pakistani militants held in Mumbai". Reuters. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- "Lashkar-e-Taiba responsible for Mumbai terroristic act". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- Mark Mazzetti (28 November 2008). "US Intelligence focuses on Pakistani Group". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Hussain, Zahid (28 July 2009). "Islamabad Tells of Plot by Lashkar". The Wall Street Journal. Islamabad. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- "Pakistan raids camp over Mumbai attacks". CNN. 8 December 2008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- "Impose Islamic dress code in colleges: LeT". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Anti-Defamation League, "LET Targets Jewish and Western Interests" 2 December 2009 Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Afghan Special Forces Arrest Key Member of Laskar-e-Taiba Militant Group - Spokesman". The Urdu Point. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "8 foreign terrorists killed, wounded as Afghan forces target Lashkar-e-Taiba compound". Khaama Press. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Abu Dujana, Ruthless Terrorist with a Weakness For Women: 10 Points". NDTV. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Lashkar-e-Taiba leader Abu Qasim killed by army, J&K police". LiveMint. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "Top Lashkar Terrorist Junaid Mattoo Killed in Jammu And Kashmir Encounter, Say Police". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- "LeT Commander Waseem Shah, The Don of Heff, Killed in Pulwama Encounter". Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi's nephew among six terrorists killed in Kashmir". 19 November 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "US embassy cables: Hillary Clinton says Saudi Arabia 'a critical source of terrorist funding'". The Guardian. 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Walsh, Declan (5 December 2010). "WikiLeaks cables portray Saudi Arabia as a cash machine for terrorists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "US embassy cables: Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists raise funds in Saudi Arabia". The Guardian. 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Lashkar militant arrested". Tribune News Service. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- "LeT has planned 10 terror strikes in India: Jundal". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- "LeT a threat to stability in South Asia, Pak should act against it: US". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Abu Jundal: Lashkar planning aerial attacks on Indian cities, has trained paragliders". 11 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- Nelson, Dean (8 October 2010). "Interpol issues Pakistan army arrest warrants over Mumbai attacks". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Lashkar-e-Taiba". Eyespymag. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Khalid Bin Abdullah Mishal Thamer Al Hameydani's Combatant Status Review Tribunal" (PDF). Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "Militant Group Expands Attacks in Afghanistan".

- "Summarized transcripts (pdf), from Taj Mohammed's Combatant Status Review Tribunal" (PDF). pp. 49–58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Summarized transcripts (.pdf), from Rafiq Bin Bashir Bin Jalud Al Hami's Combatant Status Review Tribunal Archived 10 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine – pages 20–22

- Summarized transcript (.pdf), from Abdullah Mujahid's Administrative Review Board hearing – page 206

- Summarized transcript (.pdf), from Zia Ul Shah's Administrative Review Board hearing Archived 8 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine – page 1

- "Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LT)". Center for Defense Information (CDI). 12 August 2002. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- Sri Lankan report links LTTE with LeT Dawn – 9 March 2009

- Martin, Gus (15 June 2011). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Terrorism, Second Edition. SAGE. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-4129-8016-6.

- Schmidt, Susan; Siobhan Gorman (4 December 2008). "Lashkar-e-Taiba Served as Gateway for Western Converts Turning to Jihad". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- "Statement by CIA and FBI on Arrest of Mir Aimal Kansi". Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Markon, Jerry (26 August 2006). "Teacher Sentenced for Aiding Terrorists". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- Anti-Defamation League, "Chicago Men Charged with Plotting Terrorist Attack in Denmark" 2 December 2009 Archived 1 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Anti-Defamation League, "Americans Convicted on Terrorism Charges in Atlanta" 12 June 2009 Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Anti-Defamation League, "Massachusetts Man Arrested for Attempting to Wage ‘Violent Jihad’ against America" 22 October 2009 Archived 9 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "FBI – Help Us Catch a Terrorist". Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- Miller, Joshua Rhett. "FBI offering $50G reward for Massachusetts man wanted for supporting Al Qaeda". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "FBI offering $50G reward for Massachusetts man wanted for supporting Al Qaeda". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

External links

- Profile of Lashkar-e-Taiba, Washington Post, 2008-12-05

- Profile: Lashkar-e-Taiba – BBC News

- Report on the Lashkar-e-Toiba by the Anti-Defamation League

- Report on Lashkar-e-Toiba by the South Asia Terrorism Portal

- Should Mohd. Afzal Guru be executed? International Terrorism Monitor—Paper # 132.

- Islamist Militancy in Kashmir: The Case of the Lashkar-i Tayyeba – by Prof. Yoginder Sikand

- Background on the fidayeen tactics of Lashkar-e-Toiba

- PBS report about Jamat-ud-Dawa's relief work in Kashmir

- San Francisco Chronicle article about the Ad-Dawa relief work

- Protecting the Homeland Against Mumbai-Style Attacks and the Threat from Lashkar-E-Taiba: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence of the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Thirteenth Congress, First Session, 12 June 2013