Languages in Star Wars

The Star Wars science fiction universe, created by George Lucas, features dialogue that is not spoken in natural languages. The lingua franca of the franchise, for which the language the words are dubbed or written stand in, is Galactic Basic. Characters often speak languages other than Basic, notably Shyriiwook spoken by Chewbacca, droidspeak spoken by R2-D2 and BB-8, and Huttese spoken by Jabba the Hutt.

The fictional languages were approached as sound design and developed largely by Ben Burtt, sound designer for both the original and prequel trilogy of films. He created alien dialogue out of the sounds of primarily non-English languages, such as Quechua, Haya, and Tibetan. This methodology was also used in The Force Awakens by Sara Forsberg. Lucas also insisted that written text throughout the films look as dissimilar from the English alphabet as possible, and constructed alphabets were developed.

The languages constructed for the films were criticized as not being true constructed languages, instead relying on creating the simple impression of a fully developed language. The usage of heavily accented English for alien characters was also criticized as contributing to the suggestion of racial stereotypes.

Development

Language development was approached as sound design and was handled by Ben Burtt, sound designer for both the original and prequel trilogies. He created the alien dialogue out of existing non-English language phrases and their sounds, such as Quechua for Greedo in the original Star Wars film and Haya for the character Nien Nunb in Return of the Jedi.[1] He also used English, as in the original Star Wars where he synthesized originally English dialogue from a Western film until it sounded alien.[2] Burtt said of the process: "It usually meant doing some research and finding an existing language or several languages which were exotic and interesting, something that our audience — 99 percent of them — would never understand."[3]

This methodology to create the sound of alien languages was carried into production of The Force Awakens. Director J. J. Abrams asked Sara Forsberg, who lacked a professional background in linguistics but created the viral video series "What Languages Sound Like to Foreigners" on YouTube, to develop alien dialogue spoken by Indonesian actor Yayan Ruhian.[1] Forsberg was asked to listen to "Euro-Asian languages", and she drew from Gujarati, Hindi, and other Asian languages[4] as well as Indonesian and Sundanese, Ruhian's native language.[1] She also listened to languages she did not understand to better structure the words and sentences to sound believable.[4]

During production of the prequel trilogy, Lucas insisted that written text throughout the films look as dissimilar from the English alphabet as possible and strongly opposed English-looking characters in screens and signage. In developing typefaces for use in Episode II – Attack of the Clones, including Mandalorian and Geonosian scripts, graphic artist Philip Metschan created alphabets that did not have twenty-six letters like the English alphabet.[5]

Galactic Basic

Galactic Basic, often simply Basic, is the lingua franca of the Star Wars universe, for which the language in which the works are dubbed or written acts as a stand-in.[1][6][7]

Accents

Lucas intended to balance American accents and British accents between the heroes and villains of the original film so that each side had each. He also strove to keep accents "very neutral", noting Alec Guinness's and Peter Cushing's mid-Atlantic accents and his guidance to Anthony Daniels to speak in an American accent.[8] In critical commentary on Episode I – The Phantom Menace, Patricia Williams of The Nation felt there was a correlation between accent and social class, noting that Jedi speak with "crisp British accents" while the "graceful conquered women of the Naboo" and "white slaves" such as Anakin and Shmi Skywalker "speak with the brusque, determined innocence of middle-class Americans".[6]

To decide on the sound of Nute Gunray, a Neimoidian character portrayed by Silas Carson, Lucas and Rick McCallum listened to actors from different countries reading Carson's lines. Eventually, they chose a heavily Thai-accented English, and Carson rerecorded the dialogue to mimic the Thai actor's accent.[9] Gunray's accent was described by critics to be "Hollywood Oriental" that contributed to criticism of Gunray as an Asian stereotype.[6][10][11] Watto's accent was similarly criticized as lending to anti-Semitic and anti-Arab connotations.[6][11]

Non-standard Basic

—an example of Yoda's "unusual" word order from Return of the Jedi

Yoda characteristically speaks a non-standard syntax of Basic, primarily constructing sentences in object-subject-verb word order rare in natural languages. This sentence construction is cited as a "clever device for making him seem very alien" and characterizes his dialogue as "vaguely riddle-like, which adds to his mystique". This tendency is noted to be written for an English-speaking audience; the word order is retained in Estonian subtitles, where it is grammatical but unusual and emphatic, and Yoda's dialogue is in subject–object–verb word order in Czech dubs.[12]

Gungan characters, notably Jar Jar Binks, speak in a heavily accented Basic dialect critics described as a "Caribbean-flavored pidgin",[10] "a pidgin mush of West African, Caribbean and African-American linguistic styles",[6] "very like Jamaican patois, albeit a notably reductive, even infantilized sort",[13] and suggestive of stereotypical African-American culture.[14] This was cited as a trait that led to criticism of the Gungan species as a racially offensive stereotype or caricature.[10][13][14]

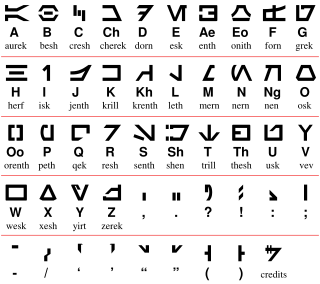

Aurebesh

Aurebesh is a writing system used to represent spoken Galactic Basic and is the most commonly seen form of written language in the Star Wars franchise.[7][15]

The alphabet was based on shapes designed by Joe Johnston for the original trilogy, which are briefly featured in screen displays in Return of the Jedi. Johnston's design, called Star Wars 76, was created into a font and again used in Attack of the Clones by Metschan, who incorporated the font alongside the later Aurebesh version used in the spin-off products.[5]

In the early 1990s, Stephen Crane, art director at West End Games, became intrigued with the shapes as they appeared on the Death Star. He sought to develop them into an alphabet to be used in West End Games' licensed Star Wars products, primarily to allow players to render their characters' names, and received permission from Lucasfilm to do so as long as it was presented as one of many alphabets in the Star Wars galaxy, not the sole and exclusive alphabet. After copying the letters from screenshots by hand, he standardized the letters based on shapes similar to the Eurostile font. He named and assigned a value to each letter, and derived the name "Aurebesh" from the names of the first two letters: aurek and besh. Once Crane completed the alphabet, Lucasfilm requested a copy to distribute to other licensees.[16]

In anticipation of the December 2015 release of The Force Awakens, Google Translate added a feature to render text into Aurebesh in November 2015.[7][15]

Other languages

Dathomiri

With only some samples of archaic speech found in Season 3 of The Clone Wars, Dathomiri is spoken primarily by the Bakura species. Mother Talzin, a Witch of Dathomir, associated with the Nightsisters is found speaking this while exorcising Darth Maul on Dathomir.

This unidentified language first appeared in April 1994 in Dave Wolverton's The Courtship of Princess Leia, when the young Teneniel Djo unleashes a Spell of Storm on Luke Skywalker and Prince Isolder of Hapes. Through retroactive continuity, though, the first real appearance of this language might be in the 1985 made-for-TV film Ewoks: The Battle for Endor. In this story, the witch Charal—who was later retconned into a Nightsister—was seen incanting over a crystal oscillator.

Droidspeak

Droidspeak is a language consisting of beeps and other synthesized sounds used by some droid characters, such as R2-D2 and BB-8.[1] Burtt created R2-D2's dialogue in the original Star Wars with an ARP 2600 analog synthesizer and by processing his own vocalizations via other effects.[17] In The Force Awakens, BB-8's dialogue was created by manipulating the voices of Bill Hader and Ben Schwartz with a talkbox running through a sound effects application on an iPad.[18] Although droidspeak is generally unintelligible to the viewing audience, it appears to be understood by characters such as Luke Skywalker.

Ewokese

The Ewoks of the forest moon of Endor speak a "primitive dialect" of one of the more than six million other forms of communication that C-3PO is familiar with. Ben Burtt, Return of the Jedi’s sound designer, created the Ewok language.

On the commentary track for the DVD of Return of the Jedi, Burtt identified the language that he heard in the BBC documentary as Kalmyk Oirat, a tongue spoken by the isolated nomadic Kalmyks. He describes how, after some research, he identified an 80-year-old Kalmyk refugee. He recorded her telling folk stories in her native language, and then used the recordings as a basis for sounds that became the Ewok language and were performed by voice actors who imitated the old woman's voice in different styles. For the scene in which C-3PO speaks Ewokese, actor Anthony Daniels worked with Burtt and invented words, based on the Kalmyk recordings.[19]

Marcia Calkovsky of Lethbridge University maintains that Tibetan language contributed to Ewok speech along with Kalmyk, starting the story from attempts to use language samples of Native Americans and later turning to nine Tibetan women living in San Francisco area, as well as one Kalmyk woman.[20] The story of the choice of these languages is referenced to Burtt's 1989 telephone interview, and many of the used Tibetan phrases translated. The initial prayer Ewoks address to C-3PO is actually the beginning part of Tibetan Buddhist prayer for the benefit of all sentient beings, or so called brahmavihāras or apramāṇas, but also there is a second (out of four) part of the refuge prayer. People of the Tibetan diaspora were puzzled as many of the phrases they could make out did not correlate to events on screen.

Rodian

In the original Star Wars film, Greedo speaks an unspecified alien language, later identified as Rodian, which is understood by Han Solo[21], before the latter kills the bounty hunter. Bruce Mannheim described Greedo as speaking "morphologically well-formed" phrases of Southern Quechua, though the sentence is ultimately meaningless. Allen Sonnefrank, a Quechua speaker and linguistic anthropology student at University of California, Berkeley, claimed Lucasfilm contacted him to record Quecha dialogue for the film. Because he was told the dialogue was to be played backward for the film, Sonnefrank refused to record the dialogue, feeling it to be a "potentially exploitative move best made by one whose first language was Quechua, if at all".[22]

Huttese

Another lingua franca in the Star Wars Universe that is spoken by many groups and species is Huttese, spoken on Nal Hutta, Nar Shaddaa, Tatooine and other worlds in and around the Hutt Space (this is the name of the zone, in the galactic West, which is illegally controlled by the Hutts and, in the Star Wars Legends continuity, covers the dominions of the former Hutt Empire). It is spoken in the films by both non-humans (Jabba the Hutt, Watto, Sebulba and others) and humans. In fact, the whole Max Rebo Band communicates and sings in Huttese. Its phonology is said to be based on the Quechuan languages.[23]

Many Huttese alphabets are featured through the franchise (most notably Boonta alphabet and Nal Huttese), but the one considered "canonical" by fans is the one found on promotional Pizza Hut pizza boxes[24][25].

Jawaese and Jawa trade language

The Jawas, also found on Tatooine, speak in a high-pitched, squeaky voice. To speak to others of their species along with the voice they emit a smell showing their emotions. https://www.starwars.com/news/much-to-learn-you-still-have-7-things-you-might-not-know-about-jawas . When trading droids and dealing with non-Jawas they speak without the smell because many consider the smell "foul". A famous exclamation in Jawaese is "Utinni!", as screamed by a Jawa to the others in A New Hope, shortly after blasting R2-D2.

Mando'a

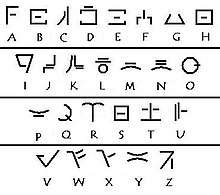

A written form of the Mandalorian language was developed by Metschan for the display screens of Jango Fett's ship Slave I in Attack of the Clones,[5] and it was later reused in The Clone Wars and Rebels.[26][27] Composer Jesse Harlin, needing lyrics for the choral work he wanted for the 2005 Republic Commando video game, invented a spoken form, intending it to be an ancient language. It was named "Mando'a" and extensively expanded by Karen Traviss, author of the Republic Commando novel series.[28]

Mando'a is characterized as a primarily spoken, agglutinative language that lacks grammatical gender in its nouns and pronouns.[29][30] The language is also characterized as lacking a passive voice, instead primarily speaking in active voice.[29] It is also described as having three grammatical tenses—present, past, and future—but it is said to be often vague and its speakers typically do not use tenses other than the present.[29][31] The language is described as having a mutually intelligible dialect called "Concordian" spoken on the planet Concord Dawn, as stated in Traviss's novels Order 66 and 501st,[32][33] and a dialect spoken on Mandalore's moon Concordia is heard in "The Mandalore Plot", a season two episode of The Clone Wars.[34]

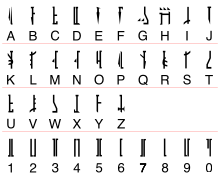

Sith

The Sith language, intended to be spoken by Sith characters, was created by Ben Grossblatt for the Book of Sith, published in February 2012. Development on the language and accompanying writing system began in November 2010. Grossblatt sought to create a pronounceable language that was not "cartoonish" and "would conform to the patterns of principles of [human] [sic] language. He felt that it needed to "feel martial and mystical" and be a "suitable, aesthetically-pleasing vehicle for communication". He characterized the sound of the language as "tough—but not barbarous" and as "convey[ing] a kind of confident, elegant cruelty". To achieve "formal, quasi-military" and "imposing, undeniable" qualities, he preferred closed syllables, creating brisk and choppy words, and constructed the language as agglutinative.[35]

Shyriiwook

Shyriiwook, also known as Wookieespeak,[3] is a language consisting largely of roars and growls spoken by Wookiee characters, notably Chewbacca. Non-Wookiee characters are capable of understanding Shyriiwook, such as Chewbacca's friend Han Solo.[22] Chewbacca's dialogue was created from recordings of walruses, camels, bears, and badgers from Burtt's personal sound library. One of the most prominent elements was an American black bear living in the Happy Hollow Park & Zoo in San Jose, California. These sounds were mixed in different ratios to create different roars.[36]

Tusken Raiders

The Tusken Raiders of Tatooine, according to the video game Knights of the Old Republic, speak a language of their own; it is difficult for non-Tuskens to understand this language. In the game, a droid named HK-47 assists the player in communicating with the Tusken Raiders. In the novelizations Junior Jedi Knights and New Jedi Order series, it is revealed that Jedi Knight Tahiri Veila was raised by the Tusken Raiders after they captured her in a raid. Generally, they utter roars and battle cries when seen in public.

Ubese

Ubese is a language heard in Return of the Jedi during a scene where a disguised Princess Leia bargains with Jabba the Hutt through translator C-3PO. Leia repeats the same Ubese phrase three times, translated differently in subtitles and by C-3PO each time. David J. Peterson, linguist and creator of constructed languages, cited his attempt as a young fan to reconcile this apparent impossibility as an example of how even casual fans may notice errors in fictional constructed languages.[37] He characterized Ubese as a "sketch" of a language rather than a fully developed language and categorized it as a "fake language" intended to "give the impression of a real language in some context without actually being a real language".[38] Ultimately, he criticized Ubese as "poorly constructed and not worthy of serious consideration".[39]

Critical commentary

Ben Zimmer labeled the method of language construction in Star Wars "a far cry" from that of constructed languages like Klingon, Na'vi, and Dothraki,[1] and he described the use of language as "never amount[ing] to more than a sonic pastiche".[40]

Linguistic anthropologist Jim Wilce summarized analyses of language in Star Wars conducted through the Society for Linguistic Anthropology's electronic mailing list. David Samuels described the approach to language as instrumental and compared the films to a Summer Institute of Linguistics convention, in which "there are no untranslatable phrases, and everyone can understand everyone else", and pointed out that the "idea that the Force is something that would be understood differently in the context of different grammars is never broached". Hal Schiffmann made five observations about language in Star Wars: all humans speak English and no other real-world language, there is "mutual passive bilingualism" in which characters speaking different languages understand one another, non-human creatures may have their own languages but are translated by C-3PO, certain non-English vocalizations serve to confuse or amuse the audience rather than serve as language, even non-English speaking characters are expected to understand English. Zimmer supported Schiffmann's claim that untranslated alien languages are not representations of real languages by pointing to the film's script, which describes the language of the Jawas as "a queer, unintelligible language" and that of the Tusken Raiders as "a coarse, barbaric language". Wilce also pointed out discussion on the usage of real non-English to create the "Otherness" of characters such as Jabba the Hutt, Greedo, and the Ewoks.[22]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Zimmer, Ben (January 15, 2016). "The Languages of 'Star Wars: The Force Awakens'". Word on the Street. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 25, 2016. (subscription required)

- Ken Rowand (August 1982). "Interview: Ben Burtt". Bantha Tracks. No. 17. Official Star Wars Fan Club. p. 2.

- Katzoff, Tami (May 24, 2013). "'Return Of The Jedi' Turns 30: Secrets Of Ewok Language Revealed!". MTV. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Rizzo, Carita (December 16, 2015). "'Star Wars': YouTube Star Creates New Language For Aliens". Variety. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Holographic Artist: Philip Metschan". Lucasfilm. July 16, 2002. Archived from the original on October 22, 2004. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Williams, Patricia J. (June 17, 1999). "Racial Ventriloquism". The Nation. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- McKalin, Vamien (November 27, 2015). "Google Translate's 'Star Wars' Easter Egg Adds Support For Aurebesh". Tech Times. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Scanlon, Paul (August 25, 1977). "George Lucas: The Wizard of Star Wars". The Rolling Stone.

- Chernoff, Scott (May 30, 2002). "Silas Carson: Hero with a Thousand Faces". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Harrison, Eric (May 26, 1999). "A Galaxy Far, Far Off Racial Mark?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Leo, John (July 4, 1999). "Fu Manchu on Naboo". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- LaFrance, Adrienne (December 18, 2015). "An Unusual Way of Speaking, Yoda Has". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- Conley, Tim; Cain, Stephen (2006). Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages. Greenwood. pp. 173–176. ISBN 978-0313331886.

- Okwu, Michael (June 14, 1999). "Jar Jar jarring". CNN. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Novet, Jordan (November 25, 2015). "Google's latest Star Wars easter egg is Aurebesh support in Google Translate". VentureBeat. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Crane, Stephen (October 21, 2000). "Aurebesh Soup". EchoStation.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- Ben Burtt. Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope audio commentary (DVD).

- McWeeny, Drew (December 15, 2015). "Wait a minute... who played the voice of BB-8 in Star Wars: The Force Awakens?". HitFix. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Ben Burtt, DVD commentary on The Return of the Jedi.

- Canadian Anthropology Society (1991). Culture. Canadian Anthropology Society. p. 59.

- Peterson, Mark Allen (May 2008). "Linguistic Moments in the Movies" (PDF). Anthropology News. Society for Linguistic Anthropology. 49 (5): 67. doi:10.1525/an.2008.49.5.67.1. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Wilce, Jim (October 1999). "Linguists in Hollywood". Anthropology News. Society for Linguistic Anthropology. 40 (7): 9–10. doi:10.1111/an.1999.40.7.9.

- Segreda, Ricardo (2009). V!VA Travel Guides: Peru. Viva Publishing Network. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-9791264-3-7.

- http://www.completewermosguide.com/huttese.html

- Unidentified Tatooinian alphabet on Wookieepedia, a Star Wars wiki

- "The Academy Trivia Gallery". StarWars.com. Lucasfilm. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- "Visions and Voices Trivia Gallery". StarWars.com. Lucasfilm. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- Bielawa, Justin (March 8, 2006). "Commando Composer: An Interview with Jesse Harlin". MusicOnFilm.net. Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- Traviss, Karen (February 2006). "No Word for Hero: The Mandalorian Language". Star Wars Insider. No. 86. IDG Entertainment. pp. 25–26.

- Traviss, Karen (October 30, 2007). Star Wars Republic Commando: True Colors. Del Rey. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-345-49800-7.

It was the same word for "mother" or "father". Mando’a didn’t bother with gender.

- Traviss, Karen (February 28, 2006). Star Wars Republic Commando: Triple Zero. Del Rey. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-345-49009-4.

I thought you Mando’ade lived only for the day. You even have trouble using anything but the present tense.

- Traviss, Karen (May 19, 2009). Star Wars Republic Commando: Order 66 (Reprint ed.). Del Rey. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-345-51385-4.

It wasn’t Mando’a, but it was close enough for any Mandalorian to understand.

- Traviss, Karen (October 27, 2009). Star Wars Imperial Commando: 501st. Del Rey. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-345-51113-3.

In Concordian, the Concord Dawn dialect of Mando’a, the phrase—brother, sister—sounded very similar.

- Hsu, Melinda (January 29, 2010). "The Mandalore Plot". Star Wars: The Clone Wars. Season 2. Episode 12. Event occurs at 7:57.

He was speaking in the dialect they use on Concordia, our moon.

- Grossblatt, Ben (June 2012). "Speak Like a Sith". Star Wars Insider. No. 134. Titan Magazines. pp. 40–43.

- "Star Wars: Databank | Chewbacca". Archived from the original on December 1, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- Peterson 2015, p. 3-6.

- Peterson 2015, p. 19.

- Peterson 2015, pp. 6.

- Zimmer, Ben (December 4, 2009). "Skxawng!". On Language. The New York Times. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

Bibliography

- Peterson, David J. (2015). The Art of Language Invention. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-312646-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Ben Burtt, Star Wars: Galactic Phrase Book & Travel Guide, ISBN 0-345-44074-9.

- Stephen Cain, Tim Conley, and Ursula K. Le Guin, Star Wars, Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006), 173-176.

External links

- Language on Wookieepedia, a Star Wars wiki