The Doll (novel)

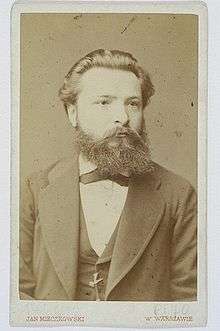

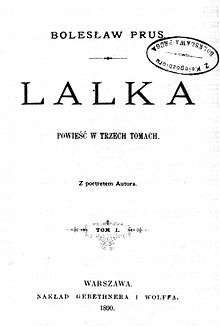

The Doll (Polish: Lalka) is the second of four acclaimed novels by the Polish writer Bolesław Prus (real name Aleksander Głowacki). It was composed for periodical serialization in 1887–1889 and appeared in book form in 1890.

| |

| Author | Bolesław Prus |

|---|---|

| Original title | Lalka |

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Sociological novel |

| Publisher | Gebethner i Wolff |

Publication date | newspaper, 1887–1889; book form, 1890 |

| Media type | Newspaper, hardback, paperback |

The Doll has been regarded by some, including Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz, as the greatest Polish novel.[1] According to Prus biographer Zygmunt Szweykowski, it may be unique in 19th-century world literature as a comprehensive, compelling picture of an entire society.

While The Doll takes its fortuitous title from a minor episode involving a stolen toy, readers commonly assume that it refers to the principal female character, the young aristocrat Izabela Łęcka. Prus had originally intended to name the book Three Generations.

The Doll has been translated into twenty-eight languages, and has been produced in several film versions and as a television miniseries.

Structure

The Doll, covering one and a half years of present time, comprises two parallel narratives. One opens with events of 1878 and recounts the career of the protagonist, Stanisław Wokulski, a man in early middle age. The other narrative, in the guise of a diary kept by Wokulski's older friend Ignacy Rzecki, takes the reader back to the 1848-49 "Spring of Nations."

Bolesław Prus wrote The Doll with such close attention to the physical detail of Warsaw that it was possible, in the Interbellum, to precisely locate the very buildings where, fictively, Wokulski had lived and his store had been located on Krakowskie Przedmieście.[2] Prus thus did for Warsaw's sense of place in The Doll in 1889 what James Joyce was famously to do for his own capital city, Dublin, in the novel Ulysses a third of a century later, in 1922.

Plot

Wokulski begins his career as a waiter at Hopfer's, a Warsaw restaurant. The scion of an impoverished Polish noble family dreams of a life in science. After taking part in the failed 1863 Uprising against the Russian Empire, he is sentenced to exile in Siberia. On eventual return to Warsaw, he becomes a salesman at Mincel's haberdashery. Marrying the late owner's widow (who eventually dies), he comes into money and uses it to set up a partnership with a Russian merchant he had met while in exile. The two merchants go to Bulgaria during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, and Wokulski makes a fortune supplying the Russian Army.

The enterprising Wokulski now proves a romantic at heart, falling in love with Izabela, daughter of the vacuous, bankrupt aristocrat, Tomasz Łęcki.

The manager of Wokulski's Warsaw store, Ignacy Rzecki, is a man of an earlier generation, a modest bachelor who lives on memories of his youth, which was a heroic chapter in his own life and that of Europe. Through his diary the reader learns about some of Wokulski's adventures, seen through the eyes of an admirer. Rzecki and his friend Katz had gone to Hungary in 1848 to enlist in the revolutionary army. For Rzecki, the cause of freedom in Europe is connected with the name of Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Hungarian revolution had sparked new hopes of abolishing the reactionary system that had triumphed at Napoleon's fall. Later he had reposed his hopes in Napoleon III. Now, as he writes, he places them in Bonaparte's scion, Napoleon III's son, Prince Loulou. At novel's end, when Rzecki hears that Loulou has perished in Africa, fighting in British ranks against rebel tribesmen, he will be overcome by the despondence of old age.

For now, Rzecki lives in constant excitement, preoccupied by politics, which he refers to in his diary by the code-letter "P." Everywhere in the press he finds indications that a long-awaited "it" is beginning.

In addition to the two generations represented by Rzecki and Wokulski, the novel provides glimpses of a third, younger one, exemplified in the scientist Julian Ochocki (modeled on Prus' friend, Julian Ochorowicz), some students, and young salesmen at Wokulski's store. The half-starving students inhabit the garret of an apartment house and are in constant conflict with the landlord over their arrears of rent; they are rebels, are inclined to macabre pranks, and are probably socialists. Also of socialist persuasion is a young salesman, whereas some of the latter's colleagues believe first and last in personal gain.

The Doll's plot focuses on Wokulski's infatuation with the superficial Izabela, who sees him only as a plebeian intruder into her rarefied world, a brute with huge red hands; for her, persons below the social standing of aristocrats are hardly human.

Wokulski, in his quest to win Izabela, begins frequenting theaters and aristocratic salons; and, to help her financially distressed father, founds a company and sets the aristocrats up as shareholders in the business.

Wokulski's eventual downfall highlights The Doll's overarching theme: the inertia of Polish society.

Alter egos

Wokulski and Rzecki are in many ways alter egos for the book's author. The frustrated scientist Wokulski is created in Prus' own image. During a visit to Paris,[3] Wokulski meets an old scientist named Geist (whose name is German for "Spirit"), who is trying to discover a metal lighter than air; in the hands of those who would use it to organize mankind, it could bring universal peace and happiness. Wokulski is torn between his misplaced, tragic love for Izabela and the idea of settling in Paris and using his fortune to perfect Geist's invention.

The Doll, rich in characters and observations from everyday Warsaw life, in Czesław Miłosz's opinion embodies 19th-century realistic prose at its best. It brings its protagonist to a full awareness of the chasm that stretches between his dreams and the social reality that surrounds him.

Translations

The Doll has been translated into twenty-eight languages: Armenian,[4] Belarusan[5], Bulgarian, Chinese[6], Croatian, Czech, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, French, Georgian, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese[7], Korean, Latvian, Lithuanian, Macedonian,[4] Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish, Ukrainian.[8]

Films

- 1968: Lalka, The Doll (1968 film), directed by Wojciech Has

- 1978: Lalka, directed by Ryszard Ber

Notes

- https://www.tygodnikpowszechny.pl/boje-sie-twojej-trzezwosci-17201

- Edward Pieścikowski, Bolesław Prus, 2nd edition, 1985, pp. 68–69.

- Prus, during his own later, 1895 visit to Paris, was pleased to find that his descriptions of Paris in The Doll, based mainly on French-language publications, had been quite accurate. (Oral account by Prus' widow, Oktawia Głowacka, cited by Tadeusz Hiż, "Godzina u pani Oktawii" ["An Hour at Oktawia Głowacka's"], in Stanisław Fita, ed., Wspomnienia o Bolesławie Prusie [Reminiscences about Bolesław Prus], p. 278.)

- Bibliografia przekładów utworów Bolesława Prusa. W: Prus. Z dziejów recepcji twórczości. Edward Pieścikowski (red.). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1988, s. 435–444. ISBN 978-83-01-05734-3.

- https://www.livelib.ru/book/1002013513-lyalka-balyasla-prus

- https://dziennikpolski24.pl/lalka-po-chinsku/ar/1699844

- "Wydanie "Lalki" Bolesława Prusa w języku japońskim" (in Polish).

- Ludomira Ryll, Janina Wilgat, Polska literatura w przekładach: bibliografia, 1945–1970 (Polish Literature in Translation: a Bibliography, 1945–1970), słowo wstępne (foreword by) Michał Rusinek, Warsaw, Agencja Autorska (Authors' Agency), 1972, pp. 149–150.

References

- Fita, Stanisław, ed. (1962). Wspomnienia o Bolesławie Prusie [Reminiscences about Bolesław Prus]. Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- Markiewicz, Henryk (1967). "Lalka" Bolesława Prusa [Bolesław Prus' The Doll]. Warsaw: Czytelnik.

- Miłosz, Czesław (1983). The History of Polish Literature (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 295–299. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Pieścikowski, Edward (1985). Bolesław Prus (2nd ed.). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 978-83-01-05593-6.

- Prus, Bolesław (1996). Tołczyk, Dariusz; Zaranko, Anna (eds.). The Doll. Translated by Welsh, David. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-1-85866-065-3.

- Szweykowski, Zygmunt (1972). Twórczość Bolesława Prusa [The Art of Bolesław Prus] (2nd ed.). Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy. pp. 152–213.

External links

- The Doll – Bolesław Prus on Culture.pl