LaMia Flight 2933

LaMia Flight 2933 was a charter flight of an Avro RJ85, operated by LaMia, that on 28 November 2016 crashed near Medellín, Colombia, killing 71 of the 77 people on board. The aircraft was transporting the Brazilian Chapecoense football squad and their entourage from Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, to Medellín, where the team was scheduled to play at the 2016 Copa Sudamericana Finals. One of the four crew members, three of the players, and two other passengers survived with injuries.

The Avro RJ85 involved, photographed in 2013 with its previous registration number | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 28 November 2016 |

| Summary | Fuel exhaustion due to pilot error |

| Site | Mt. Cerro Gordo, near La Unión, Antioquia, Colombia 5°58′43″N 75°25′6″W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Avro RJ85 |

| Operator | LaMia |

| ICAO flight No. | LMI2933 |

| Registration | CP-2933 |

| Flight origin | Viru Viru International Airport, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia |

| Destination | José María Córdova International Airport, Rionegro, Colombia |

| Occupants | 77 |

| Passengers | 73 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 71 |

| Injuries | 6 |

| Survivors | 6 |

The official report from Colombia's civil aviation agency, Aerocivil, found the causes of the crash to be fuel exhaustion, due to an inappropriate flight plan by the airline, pilot error regarding poor decision making as the situation worsened, including a failure to declare an emergency after fuel levels became critically low, thus failing to inform air traffic control at Medellin that a priority landing was required.

Background

Aircraft and operator

The aircraft was an Avro RJ85, registration CP-2933,[1] serial number E.2348,[2] which first flew in 1999.[3] After service with other airlines and a period in storage between 2010 and 2013, it was acquired by LaMia, a Venezuelan-owned airline operating out of Bolivia.[2][4]

Crew

The captain was 36-year-old Miguel Quiroga, who had been a former Bolivian Air Force (FAB) pilot and had previously flown for EcoJet, which also operated the Avro RJ85. He joined LaMia in 2013 and at the time of the accident he was one of the airline's co-owners as well as a flight instructor. Quiroga had logged a total of 6,692 flight hours, including 3,417 hours on the Avro RJ85.[5]:20[6]

The first officer was 47-year-old Fernando Goytia, who had also been a former FAB pilot. He received his type rating on the Avro RJ85 five months before the accident and had had 6,923 flight hours, with 1,474 of them on the Avro RJ85.[5]:21[7]

Another flight crew member was 29-year-old Sisy Arias, who was undergoing training and was an observer in the cockpit. She had been interviewed by TV before the flight.[8][9]

Flight and crash

The aircraft was carrying 73 passengers and 4 crew members[10]:3 on a flight from Viru Viru International Airport, in the Bolivian city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, to José María Córdova International Airport, serving Medellín in Colombia, and located in nearby Rionegro.[11] Among the passengers were 22 players of the Brazilian Associação Chapecoense de Futebol club, 23 staff, 21 journalists and 2 guests.[12] The team was travelling to play their away leg of the Final for the 2016 Copa Sudamericana in Medellín against Atlético Nacional.[13]

Background and transit to Bolivia

Chapecoense's initial request to charter LaMia for the whole journey from São Paulo to Medellín was refused by the National Civil Aviation Agency of Brazil because of freedom of the air reasons and bilateral agreements under International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) rules, which would have required the use of a Brazilian or Colombian airline for such service.[14][15][16] The club opted to retain LaMia and arranged a flight with Boliviana de Aviación from São Paulo to Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, where it was to board the LaMia flight.[17][18] LaMia had previously transported other teams for international competitions, including Chapecoense and the Argentina national team, which had flown on the same aircraft two weeks before.[4][19] The flight from São Paulo landed at Santa Cruz at 16:50 local time.[20]

Flight from Santa Cruz

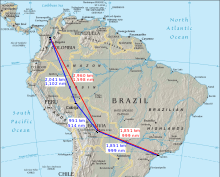

The RJ85 operating LaMia flight 2933 departed Santa Cruz at 18:18 local time.[21] A Chapecoense team member's request to have a video game retrieved from his luggage in the aircraft's cargo delayed departure.[22] The original flight plan included an intermediate refueling stop at the Cobija–Captain Aníbal Arab Airport, near Bolivia's border with Brazil;[23][18] however, the flight's late departure meant the aircraft would not arrive at Cobija prior to the airport's closing time.[3] An officer of Bolivia's Administración de Aeropuertos y Servicios Auxiliares a la Navegación Aérea (AASANA – Airports and Air Navigation Services Administration) at Santa Cruz de la Sierra reportedly rejected the crew's flight plan for a direct flight to Medellín several times despite pressure to approve it, because of the aircraft's range being almost the same as the flight distance. The flight plan was altered to include a refueling stop in Bogotá instead and was approved by another AASANA officer.[18][24] The distance between Santa Cruz and Medellín airports is 1,598 nautical miles (2,959 km; 1,839 mi).[25] A fuel stop in Cobija would have broken the flight into two segments: an initial segment of 514 nautical miles (952 km; 592 mi) to Cobija followed by a flight of 1,101 nautical miles (2,039 km; 1,267 mi) to Medellín, a total of 1,615 nautical miles (2,991 km; 1,859 mi).[25] Bogotá's airport is 1,486 nautical miles (2,752 km; 1,710 mi) from Santa Cruz's airport and 116 nautical miles (215 km; 133 mi) from Medellín's. Despite the altered flight plan, the refueling stop in Bogotá was never made, and the flight proceeded directly from Santa Cruz to Medellín.[18][24]

Under standard conditions, the RJ85 has a range of approximately 1,600 nautical miles (3,000 km; 1,800 mi) with a payload of 7,800 kilograms (17,196 lb).[26] Using the International Air Transport Association (IATA)-recommended estimate for weight of passengers and luggage of 100 kilograms (220 lb) per person,[27] the aircraft's payload is estimated at 7,700 kilograms (16,976 lb) meaning a flight from Santa Cruz to Medellín would be at the limit of the aircraft's range.

Shortly before 22:00 local time on 28 November (03:00 UTC, 29 November), the pilot of the LaMia aircraft reported an electrical failure and fuel exhaustion while flying in Colombian airspace between the municipalities of La Ceja and La Unión.[28][29] The RJ85 had begun its descent from its cruising altitude at 21:30.[26] Another aircraft had been diverted to Medellín from its planned route (from Bogotá to San Andres) by its crew because of a suspected fuel leak.[3] Medellín air traffic controllers gave that aircraft priority to land and at 21:43 the LaMia RJ85's crew was instructed to enter a racetrack-shaped holding pattern at the Rionegro VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) radio navigation beacon and wait with three other aircraft for its turn to land.[26][10]:4–5 The crew requested and were given authorisation to hold at an area navigation (RNAV) waypoint named GEMLI, about 5.4 nautical miles (10 km; 6 mi) south of the Rionegro VOR.[10]:5,7 While waiting for the other aircraft to land, during the last 15 minutes of its flight, the RJ85 completed two laps of the holding pattern. This added approximately 54 nautical miles (100 km; 62 mi) to its flight path.[30] At 21:49, the crew requested priority for landing because of unspecified "problems with fuel", and were told to expect an approach clearance in "approximately seven minutes". Minutes later, at 21:52, they declared a fuel emergency and requested immediate descent clearance and "vectors" for approach. At 21:53, with the aircraft nearing the end of its second lap of the holding pattern, engines 3 and 4 (the two engines on the right wing) flamed out due to fuel exhaustion; engines 1 and 2 flamed out two minutes later, at which point the flight data recorder (FDR) stopped operating.[3][10]:7–9

After the LaMia crew reported the RJ85's electrical and fuel problems, an air traffic controller radioed that the aircraft was 0.1 nautical miles (190 m; 200 yd) from the Rionegro VOR, but its altitude data were no longer being received.[3] The crew replied that the aircraft was at an altitude of 9,000 feet (2,700 m); the procedure for an aircraft approaching to land at José María Córdova International Airport states it must be at an altitude of at least 10,000 feet (3,000 m) when passing over the Rionegro VOR.[3] Air traffic control radar stopped detecting the aircraft at 21:55 local time as it descended among the mountains south of the airport.[3][26]

At 21:59 the aircraft hit the crest of a ridge on a mountain known as Cerro Gordo at an altitude of 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) while flying in a northwesterly direction, with the wreckage of the rear of the aircraft on the southern side of the crest and other wreckage coming to rest on the northern side of the crest adjacent to the Rionegro VOR transmitter facility, which is in line with runway 01 at José María Córdova International Airport and about 18 kilometres (9.7 nmi; 11 mi) from the southern end.[3][26][10]:15

Rescue

Helicopters from the Colombian Air Force were initially unable to get to the site because of heavy fog in the area,[1] while first aid workers arrived two hours after the crash to find debris strewn across an area about 100 metres (330 ft) in diameter.[31] It was not until 02:00 on 29 November that the first survivor arrived at a hospital: Alan Ruschel, one of the Chapecoense team members.[31] Six people were found alive in the wreckage. The last survivor to be found was footballer Neto who was discovered at 05:40.[32] Chapecoense backup goalkeeper Jakson Follmann underwent a potentially life-saving leg amputation.[33] 71 of the 77 occupants died as a result of the crash. The number of dead was initially thought to be 75, but it was later revealed that four people had not boarded the aircraft.[34] Colombian Air Force personnel extracted the bodies of 71 victims from the wreckage and took them to an air force base. They were then taken to the Instituto de Medicina Legal in Medellín for identification.[35]

Investigation

Colombian crash investigation

The Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes Aéreos (GRIAA) investigation group of Colombia's Unidad Administrativa Especial de Aeronáutica Civil (UAEAC or Aerocivil – Special Administrative Unit of Civil Aeronautics)[36] began investigating the accident and requested assistance from BAE Systems (the successor company to British Aerospace, the aircraft’s manufacturer) and the British Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) as the investigative body of the state of the manufacturer. A team of three AAIB accident investigators was deployed.[37] They were joined by investigators from Bolivia's national aviation authority, the Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil (DGAC – General Directorate of Civil Aviation).[38] In all, twenty-three specialists were deployed on the investigation; in addition to ten Colombian investigators and those from Bolivia and the United Kingdom, Brazil and the United States contributed personnel to the investigation.[39] On the afternoon of 29 November the UAEAC reported that both flight recorders – the flight data recorder (FDR) and cockpit voice recorder (CVR) – had been recovered undamaged.[1]

Evidence very quickly emerged to suggest that the aircraft had run out of fuel: the flight attendant who survived the accident reported that the captain's final words were "there is no fuel",[40][41] and transmissions to that effect from the pilots to ATC were overheard by crews of other aircraft, and recorded in the control tower.[10]:10[42] Shortly after the crash, the person leading the investigation stated that there was "no evidence of fuel in the aircraft" and the aircraft did not catch fire when it crashed.[1] Analysis of the FDR showed all four engines flamed out a few minutes before the crash.[10]:9

Four weeks after the crash the investigation confirmed that the cause of the crash was fuel exhaustion. Poor planning by the airline and poor oversight by aviation authorities in Bolivia were cited as contributory factors. Analysis by Aerocivil found that the total fuel on board was 6,570 pounds (2,980 kg) less than the mandated endurance fuel load, which legally requires: the amount required for taxi before takeoff; plus the amount required for the basic estimated time enroute at a particular altitude and onboard weight; plus allowance for extended holding patterns; plus allowance for diversions to secondary airports; plus allowance for aborted initial landing with go-around and second attempt.[43][44] The investigation found that LaMia had consistently operated its fleet without the legally required endurance fuel load, and had simply been lucky to avoid any of the delays that the mandated fuel load were meant to allow for. Due to restrictions imposed by the aircraft not being compliant with reduced vertical separation minima (RVSM) regulations, the submitted flight plan, with a nominated cruising flight level (FL) higher than 280 (approximately 28,000 feet (8,500 m) in altitude), was in violation of protocols. The flight plan, which was approved by AASANA, included a cruising altitude of FL300 (approximately 30,000 feet (9,100 m)).[45][46] The flight plan was sent for review to Colombian and Brazilian authorities as well, in accordance with regional regulations. The aircraft was estimated to be overloaded by nearly 400 kilograms (880 lb).[47] The preliminary accident report stated the CVR had recorded the pilots discussing their fuel state and possible fuel stops en route,[48] but they were so accustomed to operating with minimal fuel that they decided against a fuel stop when ATC happened to assign them an adjustment in their route which saved a few minutes of flight time.[44] For unknown reasons, the CVR stopped recording an hour and forty minutes before the FDR, when the aircraft was still about 550 nautical miles (1,020 km; 630 mi) away from the crash site at the Rionegro VOR.[10]:15 Aviation analyst John Nance and GRIAA investigators Julian Echeverri and Miguel Camacho would later suggest that the most probable explanation is that the flight's captain, who was also a part owner of LaMia, pulled the circuit breaker on the CVR to prevent a record of the subsequent discussions, knowing that the flight did not have the appropriate fuel load.[44]

Findings in the final report

On 27 April 2018, the investigators, led by Aerocivil, released the final investigative report for the crash of Flight 2933, listing the following causal factors:[5]

- The airline inappropriately planned the flight without considering the necessary amount of fuel that would be needed to fly to an alternate airport, fuel reserves, contingencies, or the required minimum fuel to land;

- The four engines shut down in sequence as a result of fuel exhaustion;

- Poor decision making by LaMia employees "as a result of processes that failed to ensure operational security";

- Poor decision making by the flight crew, who continued the flight on extremely limited fuel despite being aware of the low fuel levels aboard the aircraft and who did not take corrective actions to land the aircraft and refuel.

Additional contributing factors cited by the investigators were:

- Deploying the landing gear early;

- "Latent deficiencies" in the planning and execution of non-regular flights related to the insufficient supply of fuel;

- Specific deficiencies in the planning of the flight by LaMia;

- "Lack of supervision and operational control" by LaMia, which did not supervise the planning of the flight or its execution, nor did it provide advice to the flight crew;

- Failure to request priority or declare an emergency by the flight crew, particularly when fuel exhaustion became imminent; these actions would have allowed air traffic services to provide the necessary attention;

- Failure by the airline to follow the fuel management rules that the Bolivian DGAC had approved in certifying the company;

- Delays in CP-2933's approach to the runway resulting from its late declaration of priority and of fuel emergency, added to dense traffic in the Ríonegro VOR area.

Other investigations and disciplinary measures

Ten days after the crash, on 8 December, an investigative report by Spanish-language American media company Univision, using data from the Flightradar24 website, claimed that the airline had broken the fuel and loading regulations of the International Civil Aviation Organization on 8 of its 23 previous flights since 22 August. This included two direct flights from Medellín to Santa Cruz: one on 29 October transporting Atlético Nacional to the away leg of their Copa Sudamericana semifinal, and a flight without passengers on 4 November. The report claimed the eight flights would have used at least some of the aircraft's mandatory fuel reserves (a variable fuel quantity to allow for an additional 45 minutes of flying time), concluding the company was accustomed to operating flights at the limit of the RJ85's endurance.[49]

After the crash, the Bolivian government suspended the director of the DGAC and the chief executive of AASANA as well as the director of the DGAC’s National Aeronautics Registry—the son of one of LaMia's owners.[24][50]

Bolivian criminal investigation

A week after the crash, Bolivian police detained two individuals on criminal charges related to the crash of Flight 2933. The general director of LaMia was detained on various charges, including involuntary manslaughter.[50] His son, who worked for the DGAC, was detained for allegedly using his influence to have the aircraft be given an operational clearance. A prosecutor involved with the case told reporters that "the prosecution has collected statements and evidence showing the participation of the accused in the crimes of misusing influence, conduct incompatible with public office and a breach of duties."[51]

An arrest warrant was issued for the employee of AASANA in Santa Cruz who had refused to approve Flight 2933's flight plan - it was later approved by another official.[24][50] She fled the country seeking political asylum in Brazil, claiming that after the crash she had been pressured by her superiors to alter a report she had made before the aircraft took off and that she feared that Bolivia would not give her a fair trial.[51] A warrant was also issued for the arrest of another of LaMia's co-owners, but he still had not been located four weeks after the crash.[47]

In May 2017, a CNN report revealed that LaMia's insurance policy with Bolivian insurer Bisa had lapsed beginning in October 2016 for nonpayment; while said policy did not cover flights to Colombia, which the insurer included as part of a geographical exclusion clause along with several African countries, as well as Peru, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq, the airline managed to get permission to fly to Colombia on at least eight occasions.[52]

Reactions

Governmental

Following the crash, the DGAC of Bolivia suspended LaMia's air operator's certificate.[24][53] LaMia's remaining two RJ85s were impounded.[50] A few days after the crash, Bolivia's Defense Minister expressed concern over the possibility of aviation sanctions and downgrades by foreign national aviation authorities, for which consequences may include banning Bolivian carriers from foreign airspace.[54]

Brazilian President Michel Temer declared three days of national mourning and requested that personnel from Brazil's embassy to Colombia in Bogotá be moved to Medellín to better assist the survivors and the families of the victims.[55]

Sports

Many South American football teams paid tribute to Chapecoense by changing their playing kits to include Chapecoense's badge or wearing Chapecoense's playing kit or green colours. Matches all over the world also began with a minute of silence.[56][57][58][59]

CONMEBOL

All activities related to CONMEBOL (the South American Football Confederation) were suspended immediately, including both legs of the Copa Sudamericana final, scheduled for 30 November and 7 December,[60] and the second leg of the Copa do Brasil Final.[61] Atlético Nacional, Chapecoense's opponents-to-be in the final, asked CONMEBOL to honor Chapecoense by awarding them the Copa Sudamericana title, stating that "for our part, and forever, Chapecoense are champions of the 2016 Copa Sudamericana".[62] CONMEBOL officially named Chapecoense the 2016 Copa Sudamericana champions on 5 December.[63] The Brazilian team received the winner's prize money (US $2 million) and was awarded qualification to the 2017 Copa Libertadores, 2017 Recopa Sudamericana against Atlético Nacional and the 2017 Suruga Bank Championship against J1 League champions Urawa Red Diamonds.[64] Atlético Nacional also received the CONMEBOL Centennial Fair Play Award in recognition of its sportsmanship in suggesting that Chapecoense be awarded the title.[65]

FIFA

FIFA president Gianni Infantino gave a speech at Arena Condá, Chapecoense's stadium, at a public memorial. A committee representing FIFA at the service was composed of former football legends Clarence Seedorf and Carles Puyol; and Real Madrid player Lucas Silva. Infantino gave his speech at the end of the service by saying: "Today we are all Brazilians, we are all Chapecoenses".[66] Nacional were awarded the FIFA Fair Play Award for requesting the Copa Sudamerica title to be awarded to Chapecoense.[67]

UEFA

UEFA officially asked for a minute's silence at all upcoming Champions League and Europa League matches as a mark of respect.[68][69] President Aleksander Ceferin said in a statement: "European football is united in expressing its deepest sympathy to Chapecoense, the Brazilian football confederation, CONMEBOL and the families of all the victims following this week's air disaster".[70]

National football associations

The Argentine Football Association sent a support letter to Chapecoense offering free loans of players from Argentine clubs.[71]

The Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) encouraged Chapecoense to play its next scheduled Campeonato Brasileiro Série A game against Clube Atlético Mineiro, part of the final round of the tournament, as a tribute to the players.[72] Both Chapecoense and Atlético Mineiro refused to play the match, but they were not fined by the Superior Court of Sports Justice.[73]

Besides changing their profile pictures on social media to a black version of Chapecoense's badge and issuing messages of solidarity,[74] other Brazilian teams offered to loan the club players for the next year[60] and asked the CBF to exempt Chapecoense from relegation for the next three years.[75]

In Colombia, a four-hour tribute took place at Atlético Nacional's stadium at the time the match Chapecoense had been scheduled to play would have kicked off. This was attended by 40,000 spectators with live coverage on Fox Sports and a live stream on YouTube.[76][77]

The Uruguayan Football Association declared two days of mourning.[78] The association's referees wore a Chapecoense badge on their shirts for the 14th matchday of the Uruguayan Primera División.[79]

Other

Avianca, Colombia's flag carrier and largest airline, provided 44 psychologists to help in the counseling of the families of the victims. The airline, by request of the Colombian and Brazilian governments, also provided logistical support and transportation to Brazilian medical personnel who were involved in the identification of the deceased.[80] On Twitter, Avianca expressed its regrets over the incident and stated that "our prayers are with the families of the victims".[81]

Two weeks after the crash on 15 December, LaMia's lawyer announced that the airline had agreed with the International Civil Aviation Organization to a compensation scheme that would pay US$165,000 to each deceased passenger's family. LaMia's liability coverage insured up to a maximum of $25 million for passengers and $1.5 million for crew members.[82]

During an interview, Roberto Canessa, a member of a Uruguayan rugby team that was travelling to a match in 1972 when their aircraft crashed in what became known as the Andes flight disaster, said that he wanted to help the crash survivors.[83]

Spanish club FC Barcelona offered to play a friendly fundraiser, in order to help rebuild Chapecoense's team. The match was played on 7 August 2017 at Barcelona's stadium, which Barcelona subsequently won 5–0. Alan Ruschel, one of the three surviving players, played his first game since the tragedy. He started the game as the captain, and was substituted in the 35th minute.

In all copies of FIFA 17, players were given the Chapecoense emblem for free to wear for their FIFA Ultimate Team Club.[84]

Survivors

The surviving players were Alan Ruschel, Jakson Follmann[85] and Neto.[32] The other survivors were a flight attendant and two passengers.[10]:12 One of the surviving passengers, an employee of a Bolivian company contracted by LaMia to provide maintenance technicians to accompany the aircraft, said that there was no announcement by the pilots that there was an emergency and he thought the aircraft was simply descending prior to the crash.[86] Chapecoense goalkeeper Danilo was initially reported to have survived the crash and to have been taken to a hospital, where he later succumbed to his injuries.[87] However, the San Vicente Fundación hospital from Medellín clarified a few days later that he died in the crash.[88]

Brazilian radio personality Rafael Henzel, who was a passenger on the flight and the only journalist to survive, died on 26 March 2019 after a heart attack.[89]

Notable fatalities

Chapecoense players

- Ailton Cesar Junior Alves da Silva (Canela), 22[90]

- Dener Assunção Braz (Dener), 25[90]

- Marcelo Augusto Mathias da Silva (Marcelo), 25[90]

- Matheus Bitencourt da Silva (Matheus Biteco), 21[90]

- Mateus Lucena dos Santos (Caramelo), 22[90]

- Guilherme Gimenez de Souza (Gimenez), 21[90]

- Lucas Gomes da Silva (Lucas Gomes), 26[90]

- Everton Kempes dos Santos Gonçalves (Kemps), 34[90]

- Arthur Brasiliano Maia (Arthur Maia), 24[90]

- Ananias Eloi Castro Monteiro (Ananias), 27[90]

- Marcos Danilo Padilha (Danilo), 31[90]

- Filipe José Machado (Filipe Machado), 32[90]

- Sérgio Manoel Barbosa Santos (Sérgio Manuel), 27[90]

- José Gildeixon Clemente de Paiva (Gil), 29[90]

- Bruno Rangel Domingues (Bruno Rangel), 34[90]

- Cléber Santana Loureiro (Cléber Santana), 35[91]

- Josimar Rose da Silva Tavares (Josimar), 30[90]

- William Thiego de Jesus (Thiego), 30[90]

- Tiago da Rocha Vieira Alves (Tiaguinho), 22[90]

Chapecoense staff

- Luiz Carlos Saroli (Caio Júnior), coach, 51[91][92]

Media

- Mário Sérgio Pontes de Paiva, Fox Sports commentator, former national team player and manager, 66[93]

- Paulo Julio Clement, Fox Sports, 51[94]

- Victorino Chermont, Fox Sports, 43

Guests

- Delfim de Pádua Peixoto Filho (Delfim Peixoto), Brazilian Football Confederation former vice-president, 75

In popular culture

The United States cable TV network ESPN produced an hour long story about the crash for its E:60 news magazine TV show. It focused on how one of the pilots was also a co-owner of the airline company and the effects on the survivors and on family members of the people killed in the accident.[95]

The crash of LaMia Flight 2933 was covered in "Football Tragedy", a Season 19 (2019) episode of the internationally syndicated Canadian TV documentary series Mayday.[44] The show premiered in the United States on the Smithsonian Channel's Air Disasters as "Soccer Tragedy" in November 2019.

References

- Hradecky, Simon. "Crash: LAMIA Bolivia RJ85 near Medellin on Nov 28th 2016, electrical problems, impact with terrain". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "CP-2933 LAMIA British Aerospace Avro RJ85 – cn E2348". Planespotters. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Ranter, Harro. "CP-2933 accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

The airline's general director reported in local media that the initial plans were for LaMia to fly the football team from São Paulo, Brazil to Medellín with a refueling stop at Cobija in northern Bolivia

- Torres, Fabián (29 November 2016). "Accidente avión Chapecoense: El piloto del avión siniestrado también era el dueño de la aerolínea LaMia" [Chapecoense aircraft accident: The pilot of the LaMia aircraft was also the owner of the airline]. Marca (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Final Report Accident COL-16-37-GIA Fuel Exhaustion AVRO 146-RJ85, Reg. CP2933 29 November 2015 Aircraft, La Unión, Antioquia–Colombia" (PDF). Colombia: Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Aerocivil. 27 April 2018.

- Navia, Roberto (29 November 2016). "LaMia es boliviana y uno de sus dueños falleció" [LaMia is Bolivian and one of its owners passed away]. El Deber (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Bodies of 5 Bolivians Repatriated after Colombia Plane Crash". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Diese junge Co-Pilotin starb bei dem tragischen Flugzeugabsturz - Video" [This young co-pilot died in the tragic plane crash - video]. Focus (in German). Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Sisy, la modelo que lo dejó todo por ser piloto y murió en su primer vuelo con el Chapecoense" [Sisi, the model who left everything for being a pilot and died on her first flight with the Chapecoense]. Las2orillas (in Spanish). 1 December 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Preliminary Report Investigation COL-16-37-GIA Fuel Exhaustion Accident on 29, November 2015 Aircraft AVRO 146-RJ85, Reg.CP2933 La Unión, Antioquia–Colombia" (PDF). Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Colombia. 22 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Colombia plane crash: 71 dead on Brazil soccer team's charter flight". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Plane Carrying Football Players From Brazil Crashes In Colombia". NDTV. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Plane carrying Brazilian football team Chapecoense crashes in Colombia". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Al Chapecoense lo hicieron cambiar de avión" [Chapecoense was made to change aircraft]. El Tiempo (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Phillips, Dom; Schmidt, Samantha; Murphy, Brian (29 November 2016). "Tragedy of huge proportions: Plane with a championship-bound Brazilian soccer team crashes into mountainside". Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "The Impact of International Air Service Liberalisation on Brazil" (PDF). InterVISTAS-EU Consulting Inc. July 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- Schaefer Muñoz, Sara; Jelmayer, Rogerio; Johnson, Reed (29 November 2016). "Plane Carrying Brazilian Soccer Team Crashes in Colombia". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- Domonoske, Camila (1 December 2016). "Before Deadly Crash In Colombia, Pilot Said He was out of Fuel". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

there was a planned refueling stop in Cobija, [Bolivia], but that the delay meant they'd have to refuel in Bogotá, Colombia, instead.

- "Messi y la Selección argentina viajaron en el mismo avión del accidente hace 18 días" [Messi and the Argentine team travelled in the accident aircraft 18 days ago]. Infobae (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "BoA transportó a Chapecoense sólo de San Pablo a Santa Cruz y Lamia hacia Medellin" [BoA only transported Chapecoense from São Paulo to Santa Cruz and LaMia [took them] to Medellin] (in Spanish). Bolivian Consulate in Rosario, Argentina. 29 November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "LMI2933 Crash near Medellin". Flightradar24. Flightradar24 AB. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Steinbuch, Yaron (2 December 2016). "Search for video game may be why Colombia plane didn't refuel". New York Post. NYP Holdings, Inc. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Why the Chapecoense football team's plane ran out of fuel". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

An earlier commercial flight had brought them from São Paulo in Brazil to Bolivia. The private jet was scheduled to stop for refuelling in Cobija, in Bolivia’s north.

- Uphoff, Rainer (2 December 2016). "Bolivia suspends LAMIA Bolivia's AOC". FlightGlobal. Reed Business Information. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Great Circle Mapper". www.gcmap.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Richter, Jan. "LAMIA Avro RJ-85 crashed near Medellin with 81 on board". JACDEC. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Tenth Session of the Statistics Division, Available Capacity and Average Passenger Mass" (PDF). International Civil Aviation Organization. 13 October 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Ostrower, John. "Colombia plane crash: Jet ran out of fuel, pilot said". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Accidente de Chapecoense: los rescatistas tienen que subir media hora por la montaña a pie" [Chapecoense accident: rescuers have to climb half an hour up the mountain on foot]. La Nación (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Not Enough Fuel: The Disgusting Truth About LaMia Flight 2933". Fear of Landing. Sylvia Wrigley. 2 December 2016. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Son seis los sobrevivientes del accidente aéreo en Antioquia" [Six survivors of the aircraft crash in Antioquia]. El Tiempo (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Accidente de avión en el que viajaba Chapecoense deja 75 personas muertas" [Aircraft crash involving Chapecoense leaves 75 people dead]. Caracol.tv (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Goalie Follmann's leg amputated, Neto suffering from head trauma". Fox News Latino. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Lawlor, David (29 November 2016). "Colombia plane crash: 71 dead and six survivors on flight carrying Chapecoense football team". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Corpos de vítimas de queda do voo da Chapecoense já estão todos no IML de Medellin" [Bodies of victims of the Chapecoense air crash are already at the IML in Medellín]. G1 (in Portuguese). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Investigación de accidentes e incidentes graves" [Investigation of accidents and serious incidents]. Unidad Administrativa Especial de Aeronáutica Civil (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "The AAIB is sending a team of inspectors to Colombia" (Press release). Air Accidents Investigation Branch. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Cuiza, Paulo (29 November 2016). "DGAC envía comisión de investigadores a Colombia y asegura que nave de Lamia partió de Bolivia en perfectas condiciones" [DGAC sends panel of investigators to Colombia and states that the LaMia aircraft left Bolivia in perfect condition]. La Razón (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Aerocivil presenta informe preliminar del accidente de LAMIA en Antioquia" [Aerocivil presents preliminary report on the LAMIA accident in Antioquia] (Press release) (in Spanish). Aerocivil Colombia. 26 December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Hartley-Parkinson, Richard. "Final panicked words of pilot in Colombian plane crash as he 'ran out of fuel'". Metro. Associated Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Brazilian football team's plane crashes in Colombia killing 76". Sky News. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Soccer crash survivors treated in Colombia as investigation begins". Reuters UK. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Diamond, Cody (8 December 2016). "LAMIA Bolivia 2933: Always a Lesson to be Learned". Airways. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "Football Tragedy". Mayday. Season 19. Episode 9. Cineflix. 4 March 2019. Discovery Channel Canada.

- "Colombia afirma que LaMia y Aasana violaron protocolos" [Colombia finds that LaMia and AASANA violated protocols] (in Spanish). 27 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Plan de Vuelo" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Plane carrying Chapecoense team ran out of fuel before crashing". Sky News. Sky UK. 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "Aerocivil presenta informe preliminar del accidente de LAMIA en Antioquia" [Aerocivil presents preliminary report on the LAMIA accident in Antioquia]. Youtube (in Spanish). Aerocivil Colombia. 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Zafra, Mariano (8 December 2016). "Antes de estrellarse, el avión de LaMia forzó la reserva de combustible en otros ocho vuelos" [Before the crash, the LaMia aircraft breached fuel reserves on eight other flights]. Univision (in Spanish). Univision Communications Inc. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Lamia Chief Appears in Court after Being Charged with Manslaughter". Latin American Herald. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Colombia plane crash: Second Bolivian suspect charged". BBC News. 10 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Barón, Francho (25 May 2017). "Exclusiva: El avión del Chapecoense tenía el seguro suspendido y no podía volar a Colombia" [Exclusive: Chapecoense plane had suspended insurance and could not fly to Colombia]. CNN en Español (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "Chapecoense air crash: Bolivia suspends LaMia airline". BBC News. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Flores, Paola; Goodman, Joshua (3 December 2016). "Bolivia minister: country could face US aviation downgrade". Washington Post. The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Temer decreta luto de três dias pela tragédia com time da Chapecoense" [Temer decrees three days of mourning after the Chapecoense team tragedy] (in Portuguese). G1. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Más solidariadad" [More solidarity]. Olé (in Spanish). 29 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Homenaje en el fútbol argentino para el Chapecoense" [Tributes for Chapecoense in Argentine football]. Elgrafico.com (in Spanish). Dutriz Hermanos S.A. de C.V. 4 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "La buena cara del fútbol uruguayo: el homenaje a Chapecoense" [The good face of Uruguayan football: the homage to Chapecoense]. Ovación (in Spanish). Montevideo: El Pais S.A. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Sierra, Jeimmy Paola (30 November 2016). "Chapecoense Homenaje: Minuto de silencio en lugar de pitazo inicial" [Chapecoense Tribute: Minute of silence before the opening whistle]. Colombia.as.com (in Spanish). AS Colombia S.P.A. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Brazil football team Chapecoense in Colombia plane crash". BBC News. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Final da Copa do Brasil é adiada após tragédia com voo da Chapecoense" [Copa do Brasil final postponed after Chapecoense flight tragedy] (in Portuguese). Globo. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Gesto de grandeza" [Grand Gesture] (in Spanish). Ole. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Chapecoense officially awarded title of Copa Sudamericana after plane crash". ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures. 7 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "CONMEBOL outorga o título Copa Sul-Americana 2016 à Chapecoense e reconhece o Atlético Nacional como Campeão Fair Play do Centenário" [CONMEBOL awards the 2016 South American Cup title to Chapecoense and recognizes Atletico Nacional as the Centennial Fair Play Champion] (in Portuguese). CONMEBOL. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Fair Play del Atlético Nacional será premiado con 1 mdd" [Fair Play of Atlético Nacional will be rewarded with one million dollars]. Eluniversal.com.mx (in Spanish). El Universal. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Tragedia de Chapecoense: Gianni Infantino estuvo en el funeral y puso a la FIFA a disposición del club" [Chapecoense Tragedy: Gianni Infantino was at the funeral and made FIFA available to the club]. Clarin.com (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Clarín Digital. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "FIFA Fair Play Award 2016 – Atletico National". FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 9 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Labellarte, Giuseppe (1 December 2016). "UEFA confirms minute's silence for Chapecoense". Sports Mole. Sports Mole Ltd. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "UEFA Champions League – Barcelona-Mönchengladbach – Mero trámite entre el Barcelona y el Gladbach" [UEFA Champions League – Barcelona-Mönchengladbach – Mere formality between Barcelona and Gladbach]. Es.uefa.com (in Spanish). UEFA. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Minuta molka za Chapecoense" [Minute of silence for Chapecoense]. zurnal24.si (in Slovenian). Zurnal24. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "La AFA dispone la cesión de jugadores a Chapecoense" [The AFA offers the transfer of players to Chapecoense]. tycsports.com (in Spanish). Tele Red Imagen S.A. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "CBF insiste que Chape cumpra último jogo: 'Tem de ser uma grande festa'" [CBF urges Chape to play last game: 'It has to be a big party']. lance.com.br (in Portuguese). Grupo LANCE!. 20 November 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "STJD nega multa para Chapecoense e Atlético-MG por W.O." [Superior Court of Sports Justice denies fines for Chapecoense and Atlético Mineiro after W.O.]. espn.uol.com.br (in Portuguese). Brazil: ESPN. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- Lang, Jack (29 November 2016). "Chapecoense fans gather in grief at football club's stadium in Brazil". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Clubes se unem para ajudar Chape com empréstimos de jogadores" [Clubs unite to help Chape by loans of players]. Globo Esporte (in Portuguese). Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Dowd, Alex. "Watch Atletico Nacional's touching live tribute to Chapecoense from site of Copa final". foxsports.com. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Hidalgo, Walter Arias (1 December 2016). "Todos con Chapecoense: sentido tributo a las víctimas de la tragedia" [All with Chapecoense: touching tribute to the victims of the tragedy]. elespectador.com (in Spanish). Bogotá: Comunican S.A. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- "Luto por Chapecoense" [Mourning for Chapecoense] (Press release) (in Spanish). Asociación Uruguaya de Fútbol. 29 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "Todos somos Chapecoense" [We are all Chapecoense]. Tenfield.com (in Spanish). Tenfield S.A. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- "La aerolínea tuvo que acudir hasta a féretros prestados" [The airline even had to resort to borrowed coffins]. ElTiempo.com (in Spanish). El Tiempo. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- @Avianca (29 November 2016). "Lamentamos profundamente lo sucedido con el vuelo Lamia 2933 en suelo antioqueño. Nuestras oraciones están con las familias de las víctimas" [We deeply regret what happened with the Lamia 2933 flight in Antioquia. Our prayers are with the families of the victims.] (Tweet) (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 December 2016 – via Twitter.

- "Bolivian airline agrees on compensation plan for Chapecoense plane crash". Global Times. Global Times. Xinhua News Agency. 16 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- "Sobreviviente del 'Milagro de los Andes': "La vida es como viene, no como uno quiere"" [Survivor of the 'Miracle of the Andes': "Life is as it comes, not how one wants it"]. CNN Edición Español (in Spanish). Cable News Network. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Mewis, Joe (30 November 2016). "Here's how FIFA 17 players can pay their own tribute to the Chapecoense victims". mirror. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- "Avião que transportava equipe da Chapecoense cai na Colômbia" [Chapecoense team aircraft crashes in Colombia and kills 76 people]. Diário de Pernambuco (in Portuguese). Jornal Diario de Pernambuco. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Sobreviviente de avión accidentado nunca supo lo que pasaba" [Survivor of crashed aircraft never knew what was happening]. Azteca Noticias (in Spanish). TV Azteca S.A.B. de C.V. Associated Press. 5 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- "Trágico accidente cerca de Medellín del avión que transportaba al equipo brasileño Chapecoense deja 76 muertos" [Tragic crash of aircraft transporting Brazilian team Chapecoense near Medellín leaves 76 dead]. BBC World (in Spanish). British Broadcasting Corporation. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Médicos desmentem versão de que Danilo teria sido levado a hospital" [Doctors deny the reports that Danilo had been taken to hospital]. Globoesporte (in Portuguese). G1. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Morre Rafael Henzel, sobrevivente da tragédia com o avião da Chapecoense

- Weaver, Matthew; Malkin, Bonnie (29 November 2016). "Colombia plane crash: Fans gather to mourn Chapecoense footballers among 75 killed – as it happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Cumming, Jason; Saravia, Laura; Smith, Alexander; Chirbas, Kurt (29 November 2016). "Plane Carrying Brazil's Chapecoense Soccer Team Crashes in Colombia". NBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Veja lista de passageiros no avião da Chapecoense que caiu na Colômbia" [See list of passengers of the Chapecoense aircraft that crashed in Colombia]. G1.Globo (in Portuguese). Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Voo da Chapecoense tinha 22 profissionais de imprensa, incluindo Mario Sergio" [Chapecoense flight had 22 media professionals, including Mario Sergio]. Estadão (in Portuguese). Grupo Estado. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Além da delegação da Chapecoense, 20 profissionais de imprensa morreram" [In addition to the Chapecoense team, 20 media professionals died]. jb.com (in Portuguese). Jornal do Brasil. 29 November 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Borden, Sam (27 November 2018). "Eternal Champions". ESPN. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

Accident reports

- "Final Report Accident COL-16-37-GIA Fuel Exhaustion AVRO 146-RJ85, Reg. CP2933 29 November 2015 Aircraft, La Unión, Antioquia–Colombia" (PDF). Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Colombia. 27 April 2018.

- "Informe Final Accidente COL-16-37-GIA Agotamiento de combustible AVRO 146-RJ85, Matrícula CP 2933 29 de noviembre de 2016La Unión, Antioquia –Colombia" (PDF) (in Spanish). Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Colombia. (in Spanish)

- "Preliminary Report Investigation COL-16-37-GIA Fuel Exhaustion Accident on 29, November 2015 Aircraft AVRO 146-RJ85, Reg.CP2933 La Unión, Antioquia–Colombia" (PDF). Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Colombia. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Informe Preliminar: Investigación COL-16-37-GIA, Agotamiento de combustible, AVRO 146-RJ85, Matrícula CP2933, 29 de Noviembre de 2016, La Unión, Antioquia – Colombia" [Preliminary Report: Investigation COL-16-37-GIA, Fuel exhaustion, AVRO 146-RJ85, Registration CP2933, 29 November 2016, La Unión, Antioquia – Colombia] (PDF) (in Spanish). Grupo de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación, Colombia. Retrieved 28 December 2016. – The Spanish version is the original and is the version of record

Further reading

- Correa, Edison Molina (2018). "O CASO DO ACIDENTE AÉREO DA CHAPECOENSE" [CHAPECOENSE AIRCRAFT CASE] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Bahia Federal University. Retrieved 23 July 2019. (thesis)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LaMia Airlines Flight 2933. |

| Wikinews has related news: |