Kazimierz

Kazimierz (Polish pronunciation: [kaˈʑimjɛʂ]; Latin: Casimiria; Yiddish: קוזמיר, romanized: Kuzimyr) is a historical district of Kraków and Kraków Old Town, Poland. Since its inception in the fourteenth century to the early nineteenth century, Kazimierz has been an independent city, a royal city of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom, a location south of the Old Town of Kraków, separated from it by a branch of the Vistula river. For many centuries, Kazimierz was a place of coexistence and interpenetration of ethnic Polish and Jewish cultures. Its northeastern part of the district was historic Jewish, and its inhabitants were forcibly relocated by the German occupying forces into the Krakow ghetto just across the river in Podgórze in 1941. Today Kazimierz is one of the major tourist attractions of Krakow and an important center of cultural life of the city.

Kazimierz | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood of Kraków | |

Plac Wolnica, a central market square in the Kazimierz district. The Polish Gothic Corpus Christi Basilica can seen in the background. | |

Kazimierz

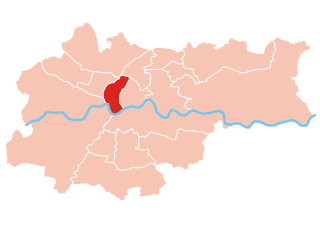

District Stare Miasto on the map of Kraków after the latest subdivisions | |

| Country | Poland |

| Voivodeship | Lesser Poland |

| County | Kraków County |

| City | Kraków |

The boundaries of Kazimierz are defined by an old island in the Vistula river. The northern branch of the river (Stara Wisła – Old Vistula) was filled-in at the end of the 19th century during the partitions of Poland and made into an extension of ul. Stradomska Street connecting Kazimierz district with Kraków Old Town.[1]

Early history

Three early medieval settlements are known to have existed on the island defining Kazimierz. The most important of these was the pre-Christian Slavic shrine at Skałka (“the little rock”) at the western, upstream tip of the island. This site, with its sacred pool, was later Christianised as the Church of St. Michael the Archangel in the 11th century and was the legendary site of the martyrdom of St. Stanisław. There was a nearby noble manor complex to the southeast and an important cattle-market town of Bawół, possibly based on an old tribal Slavic gród, at the edges of the habitable land near the swamps that composed the eastern, downstream end of the island. There was also a much smaller island upstream of Kazimierz known as the “Tatar Island” after the Tatar cemetery there. This smaller island has since washed away.

On 27 March 1335, King Casimir III of Poland (Kazimierz Wielki) declared the two western suburbs of Kraków to be a new town named after him, Kazimierz (Casimiria in Latin). Shortly thereafter, in 1340, Bawół was also added to it, making the boundaries of new city the same as the whole island. King Casimir granted his Casimiria location privilege in accordance with Magdeburg Law and, in 1362, ordered defensive walls to be built. He settled the newly built central section primarily with burghers, with a plot set aside for the Augustinian order next to Skałka. He also began work on a campus for the Kraków Academy which he founded in 1364, but Casimir died in 1370 and the campus was never completed.

Perhaps the most important feature of medieval Kazimierz was the Pons Regalis, the only major, permanent bridge across the Vistula (Polish: Wisła) for several centuries. This bridge connected Kraków via Kazimierz to the Wieliczka Salt Mine and the lucrative Hungarian trade route. The last bridge at this location (at the end of modern Stradomska Street) was dismantled in 1880 when the filling-in of the Old Vistula river bed under Mayor Mikołaj Zyblikiewicz made it obsolete.

Jewish Kazimierz

Jews had played an important role in the Kraków regional economy since the end of the 13th century, granted the freedom of worship, trade and travel by Bolesław the Pious in his General Charter of Jewish Liberties issued already in 1264. The Jewish community in Kraków had lived undisturbed alongside their ethnic Polish neighbours under the protective King Casimir III the Great, the last king of the Piast dynasty. Nevertheless, in the early 15th century pressured by the Synod of Constance some dogmatic clergy began to push for less official tolerance. Accusations of blood libel by a fanatic priest in Kraków led to riots against the Jews in 1407 even though the royal guard hastened to the rescue.[2]

As part of the re-founding of the Kraków university, starting in 1400, the Academy began to buy outbuildings in the Old Town. Some Jews moved to the area around modern Plac Szczepański.[3] The oldest synagogue building standing in Poland was built in Kazimierz at around that time, either in 1407 or 1492 (the date varies with several sources). It is an Orthodox fortress synagogue called the Old Synagogue.[4][5][6] In 1494 a disastrous fire destroyed a large part of Kraków. In 1495 the Polish king Jan I Olbracht transferred the Jews from the ravaged Old Town to the Bawół district of Kazimierz.[7] The Jewish Qahal petitioned the Kazimierz town council for the right to build its own interior walls, cutting across the western end of the older defensive walls in 1553. Due to the growth of the community and the influx of Jews from Bohemia, the walls were expanded again in 1608. Later requests to expand the walls were turned down as redundant.[8]

The area between the walls was known as the Oppidum Judaeorum, the Jewish City, which represented only about one-fifth of the geographical area of Kazimierz, but nearly half of its inhabitants. The Oppidum became the main spiritual and cultural centre of Polish Jewry, hosting many of Poland's finest Jewish scholars, artists and craftsmen. Among its famous inhabitants were the Talmudist Moses Isserles, the Court Jew Abraham of Bohemia, the Kabbalist Natan Szpiro, and the royal physician Shmuel bar Meshulam.

The golden age of the Oppidum came to an end in 1782, when the Austrian Emperor Joseph II disbanded the kahal. In 1822, the walls were torn down, removing any physical reminder of the old borders between Jewish and ethnic Polish Kazimierz.

When after 1795 (in the Third Partition of Poland) Austria acquired the city of Kraków, Kazimierz lost its status as a separate city and became a district of Kraków. The richer Jewish families quickly moved out of the overcrowded streets of eastern Kazimierz. Because of the injunction against travel on the Sabbath, however, most Jewish families stayed relatively close to the historic synagogues in the old Oppidum, maintaining Kazimierz's reputation as a “Jewish district” long after the concept ceased to have any administrative meaning. By the 1930s, Kraków had 120 officially registered synagogues and prayer houses scattered across the city and much of Jewish intellectual life had moved to new centres like Podgórze.

In a tourist guide that was published in 1935, Meir Balaban, a Reform rabbi and professor of History at the University of Warsaw, lamented that the Jews who remained in the once vibrant Oppidum were “only the poor and the ultraconservative.” However, this same exodus was the reason why most of the buildings in the Oppidum are preserved today in something close to their 18th century shape.

During the Second World War, the Jews of Krakow, including those in Kazimierz, were forced by the Nazis into a crowded ghetto in Podgórze, across the river. Most of them were later killed during the liquidation of the ghetto or in death camps.

Postwar Jewish Kazimierz

After the Second World War, devoid of Jews, Kazimierz was neglected by the communist authorities.[9] However, since 1988, now a popular annual Jewish Cultural Festival has drawn Cracovians back to the heart of the Oppidum and re-introduced Jewish culture to a generation of Poles who have grown up without Poland's historic Jewish community. In 1993, Steven Spielberg shot his film Schindler's List largely in Kazimierz (in spite of the fact that very little of the action historically took place there) and this drew international attention to Kazimierz. Since 1993, there have been parallel developments in the restoration of important historic sites in Kazimierz and a booming growth in Jewish-themed restaurants, bars, bookstores and souvenir shops. Not only that, but there are also some Jews moving to Kazimierz from Israel and America. Kazimierz with Krakow, is having a small growth in Jewish population recently.[9]

A Jewish youth group now meets weekly in Kazimierz and the Remuh Synagogue, which actively serves a small congregation of mostly elderly Cracovian Jews.

Each year at the end of June, the Jewish Culture Festival takes place in Kazimierz.[10] It is Europe's largest Jewish festival of culture and music and attracts visitors from around the world. Music at the festival is very diverse and played by bands from the Middle East, USA and Africa, amongst others.

Interior of the Tempel Synagogue Ariel Jewish restaurant, Szeroka Street, Kazimierz 2009

Kazimierz in 2009 Helena Rubinstein's birth house (green) .jpg)

Great Mikvah on Szeroka

Landau's House

Polish Jews Monument

Jan Karski Monument

Bawół Square mural. The mural takes inspiration from art nouveau era artist Ephraim Moses Lilien

Jewish Culture Festival in Kraków, annual cultural event organized since 1988 in Kazimierz

Ultra Orthodox Jews in the Szeroka Street Square

8.jpg) Remuh Cemetery established in 1535

Remuh Cemetery established in 1535

Sights

Ethnic Polish part

See map:

- 1. Market Square (Wolnica) with a town hall, now housing an ethnographic museum

- 2. Gothic St Catherine's Church

- 3. Gothic Corpus Christi Church

- 4. Baroque Church on the Rock (Skałka), the site of Saint Stanislaus's martyrdom

- 5. Municipal Engineering Museum

Jewish part

See map:

- 6. Old Synagogue, now housing a Jewish History museum

- 7. Remah Synagogue

- 8. High Synagogue

- 9. Izaak Synagogue

- 10. Kupah Synagogue

- 11. Tempel Synagogue, still active

- 12. Old Jewish Cemetery in Krakow

See also

References

- Stradomska, ulica (in) Encyklopedia Krakowa. Warszawa – Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. 2000. p. 929. ISBN 83-01-13325-2.

- S. M. Dubnow with Simon Dubnow and Israel Friedlaender (2000). History of the Jews in Russia and Poland, Volume 1. translated by Israel Friedlaender. Avotaynu Inc. pp. 22–24. ISBN 1-886223-11-4. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- Francis William Carter, Trade and Urban Development in Poland: An Economic Geography of Cracow, from Its Origins to 1795, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p.71.

- Sacred Destinations , Old Synagogue, Krakow

- The Jewish Krakow, The Old Synagogue: ul. Szeroka 24. Page stored at Internet Archive

- Rebecca Weiner, The Old Synagogue The Virtual Jewish History Tour

- Jewish Krakow, A Visual and Virtual Tour, The Kupa Synagogue: ul. Miodowa 27 from the Internet Archive

- Kazimierz.com. "Kazimierz wczoraj. Introduction". Stowarzyszenie Twórców Kazimierz.com. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "Welcome to Kazimierz!". A visual and virtual tour. Jewish Krakow.net. 2011. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- "Walking in Kazimierz District". Krakow Discovery. 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Bałaban, Majer Przewodnik po żydowskich zabytkach Krakowa Krakow: B'nei B'rith, 1935.

- Bałaban, Majer Historja Żydów w Krakowie i na Kazimierzu, 1304-1868 (Vol. I, II) Krakow: KAW, 1991. (reprint)

- Burek, Edward (ed.) Encyklopedia Krakowa. Krakow: PWM, 2000.

- Michalik, Marian (ed.) Kronika Krakowa. Krakow: Kronika, 2006.

- Simpson, Scott Krakow Cambridge: Thomas Cook, 2006.

- Świszczowski, Stefan Miasto Kazimierz pod Krakowem Krakow: WLK, 1981.

- Jakimyszyn, Anna Żydzi krakowscy w dobie Rzeczypospolitej Krakowskiej Krakow-Budapeszt 2008.

Gallery

Churches

Corpus Christi Church, 1405

Corpus Christi Church, 1405 St. Catherine Church, 1426

St. Catherine Church, 1426 Skałka, 1751

Skałka, 1751 Trinity Church, 1758

Trinity Church, 1758

Synagogues

Old Synagogue, 15th century

Old Synagogue, 15th century- Remuh Synagogue, 1557

High Synagogue, 1563

High Synagogue, 1563 Wolf Popper Synagogue, 1620

Wolf Popper Synagogue, 1620 Kupa Synagogue, 1643

Kupa Synagogue, 1643 Izaak Synagogue, 1644

Izaak Synagogue, 1644

Tempel Synagogue, 1862

Tempel Synagogue, 1862 Bne Emuna Prayerhouse, 1886. Today it houses the Judaica Foundation - Center For Jewish Culture

Bne Emuna Prayerhouse, 1886. Today it houses the Judaica Foundation - Center For Jewish Culture Chewra Thilim Synagogue, 1896. Now a restaurant.

Chewra Thilim Synagogue, 1896. Now a restaurant.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kazimierz. |

- The Jewish Cultural Festival in Krakow

- The Galicia Jewish Museum

- Jewish Community in Kazimierz on Virtual Shtetl