The Mikado

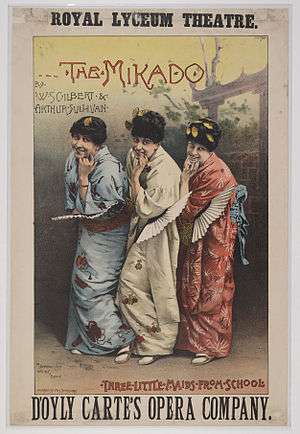

The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen operatic collaborations. It opened on 14 March 1885, in London, where it ran at the Savoy Theatre for 672 performances, the second-longest run for any work of musical theatre and one of the longest runs of any theatre piece up to that time.[1][n 1] By the end of 1885, it was estimated that, in Europe and America, at least 150 companies were producing the opera.[2]

The Mikado remains the most frequently performed Savoy Opera, and is especially popular with amateur and school productions. The work has been translated into numerous languages and is one of the most frequently played musical theatre pieces in history.

Setting the opera in Japan, an exotic locale far away from Britain, allowed Gilbert to satirise British politics and institutions more freely by disguising them as Japanese. Gilbert used foreign or fictional locales in several operas, including The Mikado, Princess Ida, The Gondoliers, Utopia, Limited and The Grand Duke, to soften the impact of his pointed satire of British institutions.

Origins

.jpg)

Gilbert and Sullivan's opera immediately preceding The Mikado was Princess Ida (1884), which ran for nine months, a short duration by Savoy opera standards.[3] When ticket sales for Princess Ida showed early signs of flagging, the impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte realised that, for the first time since 1877, no new Gilbert and Sullivan work would be ready when the old one closed. On 22 March 1884, Carte gave Gilbert and Sullivan contractual notice that a new opera would be required within six months.[4] Sullivan's close friend, the conductor Frederic Clay, had suffered a serious stroke in December 1883 that effectively ended his career. Reflecting on this, on his own precarious health, and on his desire to devote himself to more serious music, Sullivan replied to Carte that "it is impossible for me to do another piece of the character of those already written by Gilbert and myself".[5][6] Gilbert, who had already started work on a new libretto in which people fall in love against their wills after taking a magic lozenge, was surprised to hear of Sullivan's hesitation. He wrote to Sullivan asking him to reconsider, but the composer replied on 2 April 1884 that he had "come to the end of my tether" with the operas:

...I have been continually keeping down the music in order that not one [syllable] should be lost.... I should like to set a story of human interest & probability where the humorous words would come in a humorous (not serious) situation, & where, if the situation were a tender or dramatic one the words would be of similar character.[7]

Gilbert was much hurt, but Sullivan insisted that he could not set the "lozenge plot." In addition to its "improbability", it was too similar to the plot of their 1877 opera The Sorcerer. Sullivan returned to London, and, as April wore on, Gilbert tried to rewrite his plot, but he could not satisfy Sullivan. The parties were at a stalemate, and Gilbert wrote, "And so ends a musical & literary association of seven years' standing – an association of exceptional reputation – an association unequaled in its monetary results, and hitherto undisturbed by a single jarring or discordant element."[8] But by 8 May 1884, Gilbert was ready to back down, writing: "am I to understand that if I construct another plot in which no supernatural element occurs, you will undertake to set it? ... a consistent plot, free from anachronisms, constructed in perfect good faith & to the best of my ability."[9] The stalemate was broken, and on 20 May, Gilbert sent Sullivan a sketch of the plot to The Mikado.[9] It would take another ten months for The Mikado to reach the stage. A revised version of The Sorcerer coupled with their one-act piece Trial by Jury (1875) played at the Savoy while Carte and their audiences awaited their next work. Gilbert eventually found a place for his "lozenge plot" in The Mountebanks, written with Alfred Cellier in 1892.

In 1914 Cellier and Bridgeman first recorded the familiar story of how Gilbert found his inspiration:

Gilbert, having determined to leave his own country alone for a while, sought elsewhere for a subject suitable to his peculiar humour. A trifling accident inspired him with an idea. One day an old Japanese sword that, for years, had been hanging on the wall of his study, fell from its place. This incident directed his attention to Japan. Just at that time a company of Japanese had arrived in England and set up a little village of their own in Knightsbridge.[11]

The story is an appealing one, but it is largely fictional.[12] Gilbert was interviewed twice about his inspiration for The Mikado. In both interviews the sword was mentioned, and in one of them he said it was the inspiration for the opera, though he never said the sword had fallen. What puts the entire story in doubt is Cellier and Bridgeman's error concerning the Japanese exhibition in Knightsbridge:[10] it did not open until 10 January 1885, almost two months after Gilbert had already completed Act I.[12][13] Gilbert scholar Brian Jones, in his article "The Sword that Never Fell", notes that "the further removed in time the writer is from the incident, the more graphically it is recalled."[14] Leslie Baily, for instance, told it this way in 1952:

A day or so later Gilbert was striding up and down his library in the new house at Harrington Gardens, fuming at the impasse, when a huge Japanese sword decorating the wall fell with a clatter to the floor. Gilbert picked it up. His perambulations stopped. 'It suggested the broad idea,' as he said later. His journalistic mind, always quick to seize on topicalities, turned to a Japanese Exhibition which had recently been opened in the neighbourhood. Gilbert had seen the little Japanese men and women from the Exhibition shuffling in their exotic robes through the streets of Knightsbridge. Now he sat at his writing desk and picked up the quill pen. He began making notes in his plot-book.[15]

The story was dramatised in more or less this form in the 1999 film Topsy-Turvy.[16] But although the 1885–87 Japanese exhibition in Knightsbridge had not opened when Gilbert conceived of The Mikado, European trade with Japan had increased in recent decades, and an English craze for all things Japanese had built through the 1860s and 1870s. This made the time ripe for an opera set in Japan.[17] Gilbert told a journalist, "I cannot give you a good reason for our ... piece being laid in Japan. It ... afforded scope for picturesque treatment, scenery and costume, and I think that the idea of a chief magistrate, who is ... judge and actual executioner in one, and yet would not hurt a worm, may perhaps please the public."[18][19]

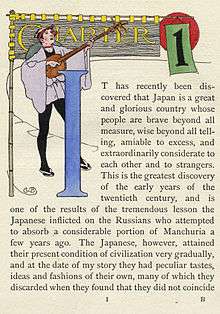

In an 1885 interview with the New York Daily Tribune, Gilbert said that the short stature of Leonora Braham, Jessie Bond and Sybil Grey "suggested the advisability of grouping them as three Japanese school-girls", the opera's "three little maids". He also recounted that a young Japanese lady, a tea server at the Japanese village, came to rehearsals to coach the three little maids in Japanese dance.[19] On 12 February 1885, one month before The Mikado opened, the Illustrated London News wrote about the opening of the Japanese village noting, among other things, that "the graceful, fantastic dancing featured... three little maids!"[20] The title character appears only in Act II of the opera. Gilbert related that he and Sullivan had decided to cut the Mikado's only solo song, but that members of the company and others who had witnessed the dress rehearsal "came to us in a body and begged us to restore [it]".[19]

Roles

- The Mikado of Japan (bass or bass-baritone)

- Nanki-Poo, His Son, disguised as a wandering minstrel and in love with Yum-Yum (tenor)

- Ko-Ko, The Lord High Executioner of Titipu (comic baritone)

- Pooh-Bah, Lord High Everything Else (baritone)

- Pish-Tush, A Noble Lord (baritone)[n 2]

- Go-To, A Noble Lord (bass-baritone)[n 2]

- Yum-Yum, A Ward of Ko-Ko, also engaged to Ko-Ko (soprano)

- Pitti-Sing, A Ward of Ko-Ko (mezzo-soprano)

- Peep-Bo, A Ward of Ko-Ko (soprano or mezzo-soprano)

- Katisha, An Elderly lady, in love with Nanki-Poo (contralto)

- Chorus of School-Girls, Nobles, Guards and Coolies

Synopsis

Act I

- Courtyard of Ko-Ko's Official Residence

Gentlemen of the fictitious Japanese town of Titipu are gathered ("If you want to know who we are"). A handsome but poor minstrel, Nanki-Poo, arrives and introduces himself ("A wand'ring minstrel I"). He inquires about his beloved, a schoolgirl called Yum-Yum, who is a ward of Ko-Ko (formerly a cheap tailor). One of the gentlemen, Pish-Tush, explains that when the Mikado decreed that flirting was a capital crime, the Titipu authorities frustrated the decree by appointing Ko-Ko, a prisoner condemned to death for flirting, to the post of Lord High Executioner ("Our great Mikado, virtuous man"). As Ko-Ko was the next prisoner scheduled to be decapitated, the town authorities reasoned that he could "not cut off another's head until he cut his own off", and since Ko-Ko was not likely to try to execute himself, no executions could take place. However, all of the town's officials except the haughty nobleman, Pooh-Bah, proved too proud to serve under an ex-tailor, and they resigned. Pooh-Bah now holds all their posts and collects all their salaries. Pooh-Bah informs Nanki-Poo that Yum-Yum is scheduled to marry Ko-Ko on the very day that he has returned ("Young man, despair").

Ko-Ko enters ("Behold the Lord High Executioner") and asserts himself by reading off a list of people "who would not be missed" if they were executed ("As some day it may happen"), such as people "who eat peppermint and puff it in your face". Yum-Yum appears with Ko-Ko's other two wards, Peep-Bo and Pitti-Sing ("Comes a train of little ladies", "Three little maids from school"). Pooh-Bah does not think that the girls have shown him enough respect ("So please you, sir"). Nanki-Poo arrives and informs Ko-Ko of his love for Yum-Yum. Ko-Ko sends him away, but Nanki-Poo manages to meet with his beloved and reveals his secret to Yum-Yum: he is the son and heir of the Mikado, but travels in disguise to avoid the amorous advances of Katisha, an elderly lady of his father's court. They lament that the law forbids them to flirt ("Were you not to Ko-Ko plighted").

Ko-Ko and Pooh-Bah receive news that the Mikado has just decreed that unless an execution is carried out in Titipu within a month, the town will be reduced to the rank of a village, which would bring "irretrievable ruin". Pooh-Bah and Pish-Tush point to Ko-Ko himself as the obvious choice for beheading, since he was already under sentence of death ("I am so proud"). Ko-Ko argues, however, that, firstly, it would be "extremely difficult, not to say dangerous", for someone to attempt their own beheading, and secondly, it would be suicide, which is a capital offence. Fortuitously, Ko-Ko discovers that Nanki-Poo, in despair over losing Yum-Yum, is preparing to commit suicide. After ascertaining that nothing would change Nanki-Poo's mind, Ko-Ko makes a bargain with him: Nanki-Poo may marry Yum-Yum for one month if, at the end of that time, he allows himself to be executed. Ko-Ko would then marry the young widow.

Everyone arrives to celebrate Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum's union ("With aspect stern and gloomy stride"), but the festivities are interrupted by the arrival of Katisha, who has come to claim Nanki-Poo as her husband. However, the townspeople are sympathetic to the young couple, and Katisha's attempts to reveal Nanki-Poo's secret are drowned out by the shouting of the crowd. Outwitted but not defeated, Katisha makes it clear that she intends to get vengeance.

Act II

- Ko-Ko's Garden.

Yum-Yum is being prepared by her friends for her wedding ("Braid the raven hair"), after which she muses on her own beauty ("The sun whose rays"). Pitti-Sing and Peep-Bo return to remind her of the limited duration of her impending union. Joined by Nanki-Poo and Pish-Tush, they try to keep their spirits up ("Brightly dawns our wedding-day"), but soon Ko-Ko and Pooh-Bah enter to inform them of a twist in the law that states that when a married man is beheaded for flirting, his wife must be buried alive ("Here's a how-de-do"). Yum-Yum is unwilling to marry under these circumstances, and so Nanki-Poo challenges Ko-Ko to behead him on the spot. It turns out, however, that the soft-hearted Ko-Ko has never executed anyone and cannot execute Nanki-Poo. Ko-Ko instead sends Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum away to be wed (by Pooh-Bah, as Archbishop of Titipu), promising to present to the Mikado a false affidavit in evidence of the fictitious execution.

Shall all be extracted

By terrified amateurs."

(Cartoon by W. S. Gilbert)

The Mikado and Katisha arrive in Titipu accompanied by a large procession ("Mi-ya Sa-Ma", "From Every Kind of Man"). The Mikado describes his system of justice ("A more humane Mikado"). Ko-Ko assumes that the ruler has come to see whether an execution has been carried out. Aided by Pitti-Sing and Pooh-Bah, he graphically describes the supposed execution ("The criminal cried") and hands the Mikado the certificate of death, signed and sworn to by Pooh-Bah as coroner. Ko-Ko notes slyly that most of the town's important officers (that is, Pooh-Bah) were present at the ceremony. However, the Mikado has come about an entirely different matter; he is searching for his son. When they hear that the Mikado's son "goes by the name of Nanki-Poo", the three panic, and Ko-Ko says that Nanki-Poo "has gone abroad". Meanwhile, Katisha is reading the death certificate and notes with horror that the person executed was Nanki-Poo. The Mikado, though expressing understanding and sympathy ("See How the Fates"), discusses with Katisha the statutory punishment "for compassing the death of the heir apparent" to the Imperial throne – something lingering, "with boiling oil ... or melted lead". With the three conspirators facing painful execution, Ko-Ko pleads with Nanki-Poo to reveal himself to his father. Nanki-Poo fears that Katisha will demand his execution if she finds he is alive, but he suggests that if Katisha could be persuaded to marry Ko-Ko, then Nanki-Poo could safely "come to life again", as Katisha would have no claim on him ("The flowers that bloom in the spring"). Though Katisha is "something appalling", Ko-Ko has no choice: it is marriage to Katisha, or a painful death for himself, Pitti-Sing and Pooh-Bah.

Ko-Ko finds Katisha mourning her loss ("Alone, and yet alive") and throws himself on her mercy. He begs for her hand in marriage, saying that he has long harboured a passion for her. Katisha initially rebuffs him, but is soon moved by his story of a bird who died of heartbreak ("Tit-willow"). She agrees ("There is beauty in the bellow of the blast") and, once the ceremony is performed (by Pooh-Bah, the Registrar), she begs for the Mikado's mercy for him and his accomplices. Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum then reappear, sparking Katisha's fury. The Mikado is astonished that Nanki-Poo is alive, as the account of his execution had been given with such "affecting particulars". Ko-Ko explains that when a royal command for an execution is given, the victim is, legally speaking, as good as dead, "and if he is dead, why not say so?"[n 3] The Mikado deems that "Nothing could possibly be more satisfactory", and everyone in Titipu celebrates ("For he's gone and married Yum-Yum").

Musical numbers

- Overture (Includes "Mi-ya Sa-ma", "The Sun Whose Rays Are All Ablaze", "There is Beauty in the Bellow of the Blast", "Braid the Raven Hair" and "With Aspect Stern and Gloomy Stride") This was arranged, under Sullivan's direction, by Hamilton Clarke.[21]

Act I

- 1. "If you want to know who we are" (Chorus of Men)

- 2. "A Wand'ring Minstrel I" (Nanki-Poo and Men)

- 3. "Our Great Mikado, virtuous man" (Pish-Tush and Men)

- 4. "Young man, despair" (Pooh-Bah, Nanki-Poo and Pish-Tush)

- 4a. Recit., "And have I journey'd for a month" (Pooh-Bah, Nanki-Poo)

- 5. "Behold the Lord High Executioner" (Ko-Ko and Men)

- 5a. "As some day it may happen" (Ko-Ko and Men)

- 6. "Comes a train of little ladies" (Girls)

- 7. "Three little maids from school are we" (Yum-Yum, Peep-Bo, Pitti-Sing, and Girls)

- 8. "So please you, Sir, we much regret" (Yum-Yum, Peep-Bo, Pitti-Sing, Pooh-Bah, and Girls)[n 4]

- 9. "Were you not to Ko-Ko plighted" (Yum-Yum and Nanki-Poo)

- 10. "I am so proud" (Pooh-Bah, Ko-Ko and Pish-Tush)

- 11. Finale Act I (Ensemble)

- "With aspect stern and gloomy stride"

- "The threatened cloud has passed away"

- "Your revels cease!" ... "Oh fool, that fleest my hallowed joys!"

- "For he's going to marry Yum-Yum"

- "The hour of gladness" ... "O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!"

- "Ye torrents roar!"

Act II

- 12. "Braid the raven hair" (Pitti-Sing and Girls)

- 13. "The sun whose rays are all ablaze" (Yum-Yum) (Originally in Act I, moved to Act II shortly after the opening night)

- 14. Madrigal, "Brightly dawns our wedding day" (Yum-Yum, Pitti-Sing, Nanki-Poo and Pish-Tush)

- 15. "Here's a how-de-do" (Yum-Yum, Nanki-Poo and Ko-Ko)

- 16. "Mi-ya Sa-ma"[22] "From every kind of man obedience I expect" (Mikado, Katisha, Chorus)

- 17. "A more humane Mikado" (Mikado, Chorus) (This song was nearly cut, but was restored shortly before the first night.)

- 18. "The criminal cried as he dropped him down" (Ko-Ko, Pitti-Sing, Pooh-Bah, Chorus)

- 19. "See how the Fates their gifts allot" (Mikado, Pitti-Sing, Pooh-Bah, Ko-Ko and Katisha)

- 20. "The flowers that bloom in the spring" (Nanki-Poo, Ko-Ko, Yum-Yum, Pitti-Sing, and Pooh-Bah)

- 21. Recit. and song, "Alone, and yet alive" (Katisha)

- 22. "On a tree by a river" ("Willow, tit-willow") (Ko-Ko)

- 23. "There is beauty in the bellow of the blast" (Katisha and Ko-Ko)

- 24. "Finale Act II" (Ensemble)

- "For he's gone and married Yum-Yum"

- "The threatened cloud has passed away"

Productions

The Mikado had the longest original run of the Savoy Operas. It also had the quickest revival: after Gilbert and Sullivan's next work, Ruddigore, closed relatively quickly, three operas were revived to fill the interregnum until The Yeomen of the Guard was ready, including The Mikado, just 17 months after its first run closed. On 4 September 1891, D'Oyly Carte's touring "C" company gave a Royal Command Performance of The Mikado at Balmoral Castle before Queen Victoria and the Royal Family.[23] The original set design was by Hawes Craven, with men's costumes by C. Wilhelm.[24][25] The first provincial production of The Mikado opened on 27 July 1885 in Brighton, with several members of that company leaving in August to present the first authorised American production in New York. From then on, The Mikado was a constant presence on tour. From 1885 until the Company's closure in 1982, there was no year in which a D'Oyly Carte company (or several of them) was not presenting it.[26]

The Mikado was revived again while The Grand Duke was in preparation. When it became clear that that opera was not a success, The Mikado was given at matinees, and the revival continued when The Grand Duke closed after just three months. In 1906–07, Helen Carte, the widow of Richard D'Oyly Carte, mounted a repertory season at the Savoy, but The Mikado was not performed, as it was thought that visiting Japanese royalty might be offended by it. It was included, however, in Mrs. Carte's second repertory season, in 1908–09. New costume designs were created by Charles Ricketts for the 1926 season and were used until 1982.[27] Peter Goffin designed new sets in 1952.[24]

In America, as had happened with H.M.S. Pinafore, the first productions were unauthorised, but once D'Oyly Carte's American production opened in August 1885, it was a success, earning record profits, and Carte formed several companies to tour the show in North America.[28] Burlesque and parody productions, including political parodies, were mounted.[29] About 150 unauthorised versions cropped up, and, as had been the case with Pinafore, Carte, Gilbert and Sullivan could do nothing about it since there was no copyright treaty at the time.[2][30] In Australia, The Mikado's first authorised performance was on 14 November 1885 at the Theatre Royal, Sydney, produced by J. C. Williamson. During 1886, Carte was touring five Mikado companies in North America.[31]

Carte toured the opera in 1886 and again in 1887 in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.[32] In September 1886 Vienna's leading critic, Eduard Hanslick, wrote that the opera's "unparalleled success" was attributable not only to the libretto and the music, but also to "the wholly original stage performance, unique of its kind, by Mr D'Oyly Carte's artists... riveting the eye and ear with its exotic allurement."[33] Authorised productions were also seen in France, Holland, Hungary, Spain, Belgium, Scandinavia, Russia and elsewhere. Thousands of amateur productions have been mounted throughout the English-speaking world and beyond since the 1880s.[34][35][36] One production during World War I was given in the Ruhleben internment camp in Germany.[37]

After the Gilbert copyrights expired in 1962, the Sadler's Wells Opera mounted the first non-D'Oyly Carte professional production in England, with Clive Revill as Ko-Ko. Among the many professional revivals since then was an English National Opera production in 1986, with Eric Idle as Ko-Ko and Lesley Garrett as Yum-Yum, directed by Jonathan Miller. This production, which has been revived numerous times over three decades, is set not in ancient Japan, but in a swanky 1920s seaside hotel with sets and costumes in white and black.[38] Canada's Stratford Festival has produced The Mikado several times, first in 1963 and again in 1982 (revived in 1983 and 1984) and in 1993.[39]

The following table shows the history of the D'Oyly Carte productions in Gilbert's lifetime:

| Theatre | Opening Date | Closing Date | Perfs. | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Savoy Theatre | 14 March 1885 | 19 January 1887 | 672 | First London run. |

| Fifth Avenue and Standard Theatres, New York | 19 August 1885 | 17 April 1886 | 250 | Authorised American production. Production was given at the Fifth Avenue Theatre, except for a one-month transfer to the Standard Theatre in February 1886. |

| Fifth Avenue Theatre, New York | 1 November 1886 | 20 November 1886 | 3 wks | Production with some D'Oyly Carte personnel under the management of John Stetson. |

| Savoy Theatre | 7 June 1888 | 29 September 1888 | 116 | First London revival. |

| Savoy Theatre | 6 November 1895 | 4 March 1896 | 127 | Second London revival. |

| Savoy Theatre | 27 May 1896 | 4 July 1896 | 6 | Performances at matinees during the original run of The Grand Duke. |

| Savoy Theatre | 11 July 1896 | 17 February 1897 | 226 | Continuation of revival after early closure of The Grand Duke. |

| Savoy Theatre | 28 April 1908 | 27 March 1909 | 142 | Second Savoy repertory season; played with five other operas. Closing date shown is of the entire season. |

Analysis and reception

Themes of death

The Mikado is a comedy that deals with themes of death and cruelty. This works only because Gilbert treats these themes as trivial, even lighthearted issues. For instance, in Pish-Tush's song "Our great Mikado, virtuous man", he sings: "The youth who winked a roving eye / Or breathed a non-connubial sigh / Was thereupon condemned to die – / He usually objected." The term for this rhetorical technique is meiosis, a drastic understatement of the situation. Other examples of this are when self-decapitation is described as "an extremely difficult, not to say dangerous, thing to attempt", and also as merely "awkward". When a discussion occurs of Nanki-Poo's life being "cut short in a month", the tone remains comic and only mock-melancholy. Burial alive is described as "a stuffy death". Finally, execution by boiling oil or by melted lead is described by the Mikado as a "humorous but lingering" punishment.

Death is treated as a businesslike event in Gilbert's topsy-turvy world. Pooh-Bah calls Ko-Ko, the Lord High Executioner, an "industrious mechanic". Ko-Ko also treats his bloody office as a profession, saying, "I can't consent to embark on a professional operation unless I see my way to a successful result." Of course, joking about death does not originate with The Mikado. The plot conceit that Nanki-Poo may marry Yum-Yum if he agrees to die at the end of the month was used in A Wife for a Month, a 17th-century play by John Fletcher. Ko-Ko's final speech affirms that death has been, throughout the opera, a fiction, a matter of words that can be dispelled with a phrase or two: being dead and being "as good as dead" are equated. In a review of the original production of The Mikado, after praising the show generally, the critic noted that the show's humour nevertheless depends on "unsparing exposure of human weaknesses and follies – things grave and even horrible invested with a ridiculous aspect – all the motives prompting our actions traced back to inexhaustible sources of selfishness and cowardice... Decapitation, disembowelment, immersion in boiling oil or molten lead are the eventualities upon which [the characters'] attention (and that of the audience) is kept fixed with gruesome persistence... [Gilbert] has unquestionably succeeded in imbuing society with his own quaint, scornful, inverted philosophy; and has thereby established a solid claim to rank amongst the foremost of those latter-day Englishmen who have exercised a distinct psychical influence upon their contemporaries."[40]

Japanese setting

The opera is named after the Emperor of Japan using the term mikado (御門 or 帝 or みかど), literally meaning "the honourable gate" of the imperial palace, referring metaphorically to its occupant and to the palace itself. The term was commonly used by the English in the 19th century but became obsolete.[41] To the extent that the opera portrays Japanese culture, style and government, it is a fictional version of Japan used to provide a picturesque setting and to capitalise on Japonism and the British fascination with Japan and the Far East in the 1880s.[17] Gilbert wrote, "The Mikado of the opera was an imaginary monarch of a remote period and cannot by any exercise of ingenuity be taken to be a slap on an existing institution."[42] The Mikado "was never a story about Japan but about the failings of the British government".[43]

By setting the opera in a foreign land, Gilbert felt able to more sharply criticise British society and institutions.[44] G. K. Chesterton compared the opera's satire to that in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels: "Gilbert pursued and persecuted the evils of modern England till they had literally not a leg to stand on, exactly as Swift did. ... I doubt if there is a single joke in the whole play that fits the Japanese. But all the jokes in the play fit the English. ... About England, Pooh-bah is something more than a satire; he is the truth."[45] The opera's setting draws on Victorian notions of the far east, gleaned by Gilbert from the glimpses of Japanese fashion and art that immediately followed the beginning of trade between the two island empires, and during rehearsals Gilbert visited the popular Japanese exhibition in Knightsbridge, London.[46] A critic wrote in 2016: "It has been argued that the theatricality of the show was ... a tribute on the part of Gilbert and Sullivan to the growing British appreciation of the Japanese aesthetic [in the 1880s]."[47]

Gilbert sought authenticity in the Japanese setting, costumes, movements and gestures of the actors. To that end, he engaged some of the Japanese at the Knightsbridge village to advise on the production and to coach the actors. "The Directors and Native Inhabitants" of the village were thanked in the programme that was distributed on the first night.[48] Sullivan inserted into his score, as "Miya sama", a version of a Japanese military march song, called "Ton-yare Bushi", composed in the Meiji Era.[22][49][50] Giacomo Puccini later incorporated the same song into Madama Butterfly as the introduction to Yamadori, ancor le pene. The characters' names in the play are not Japanese names, but rather (in many cases) English baby-talk or simply dismissive exclamations. For instance, a pretty young thing is named Pitti-Sing; the beautiful heroine is named Yum-Yum; the pompous officials are Pooh-Bah[n 5] and Pish-Tush;[n 6] the hero is called Nanki-Poo, baby-talk for "handkerchief".[51][52][53] The headsman's name, Ko-Ko, is similar to that of the scheming Ko-Ko-Ri-Ko in Ba-ta-clan by Jacques Offenbach.[54]

The Japanese were ambivalent toward The Mikado for many years. Some Japanese critics saw the depiction of the title character as a disrespectful representation of the revered Meiji Emperor; Japanese theatre was prohibited from depicting the emperor on stage.[55] Japanese Prince Komatsu Akihito, who saw an 1886 production in London, took no offence.[56] When Prince Fushimi Sadanaru made a state visit in 1907, the British government banned performances of The Mikado from London for six weeks,[n 7] fearing that the play might offend him – a manoeuvre that backfired when the prince complained that he had hoped to see The Mikado during his stay.[57][58] A Japanese journalist covering the prince's stay attended a proscribed performance and confessed himself "deeply and pleasingly disappointed." Expecting "real insults" to his country, he had found only "bright music and much fun."[59]

After World War II, The Mikado was staged in Japan in a number of private performances. The first public production, given at three performances, was in 1946 in the Ernie Pyle Theatre in Tokyo, conducted by the pianist Jorge Bolet for the entertainment of American troops and Japanese audiences. The set and costumes were opulent, and the principal players were American, Canadian, and British, as were the women's chorus, but the male chorus, the female dancing chorus and the orchestra were Japanese.[60] General Douglas MacArthur banned a large-scale professional 1947 Tokyo production by an all-Japanese cast,[61] but other productions have occurred in Japan. For example, the opera was performed at the Ernie Pyle Theatre in Tokyo in 1970, presented by the Eighth Army Special Service.[62]

In 2001, the town of Chichibu (秩父), Japan, under the name of "Tokyo Theatre Company", produced an adaptation of The Mikado in Japanese.[63][64] Locals believe that Chichibu was the town Gilbert had in mind when he named his setting "Titipu", but there is no contemporary evidence for this theory.[65] Although the Hepburn system of transliteration (in which the name of the town appears as "Chichibu") is usually found today, it was very common in the 19th century to use the Nihon-shiki system, in which the name 秩父 appears as "Titibu". Thus it is easy to surmise that "Titibu", found in the London press of 1884, became "Titipu" in the opera. Japanese researchers speculate that Gilbert may have heard of Chichibu silk, an important export in the 19th century. The town's Japanese-language adaptation of The Mikado has been revived several times throughout Japan and, in 2006, the Chichibu Mikado was performed at the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival in England.[66]

Criticism

Since the 1990s, the opera, and productions of it, have sometimes drawn criticism from the Asian-American community as promoting "simplistic orientalist stereotypes".[67] In 2014, after a production in Seattle, Washington, drew national attention to such criticism,[68] the Gilbert biographer Andrew Crowther wrote that The Mikado "does not portray any of the characters as being 'racially inferior' or indeed fundamentally any different from British people. The point of the opera is to reflect British culture through the lens of an invented 'other', a fantasy Japan that has only the most superficial resemblance to reality."[69] For example, the starting point for the plot of The Mikado is "an invented 'Japanese' law against flirting, which makes sense only as a reference to the sexual prudishness of British culture".[69] Crowther noted that production design and other features of traditionally staged productions of the opera often "do look somewhat insensitive, not to say insulting. ... It should [be possible] to avoid such things in the future, with a little sensitivity. ... G&S is about silliness, and fun, and ... mocking the powerful, and accepting the fundamental absurdity of life".[69] Some commentators dismissed the criticism as political correctness[70] but a public discussion of the issue in Seattle a month later drew a large crowd who nearly all agreed that, although works like The Mikado should not be abandoned in their traditional form, there should be "some kind of contextualizing apparatus to show that the producers and performers are at least thinking about the problems in the work".[71]

In 2015 a planned production by the New York Gilbert and Sullivan Players was withdrawn after its publicity materials ignited a similar protest in the Asian-American blogosphere. The company redesigned its Mikado production[72] and debuted the new concept in December 2016, receiving a warm review from The New York Times.[73] After Lamplighters Music Theatre of San Francisco planned a 2016 production, objections by the Asian-American community prompted them to reset the opera in Renaissance-era Milan, eliminating all references to Japan.[74] Reviewers felt that the change resolved the issue.[75]

Modernised words and phrases

Modern productions update some of the words and phrases in The Mikado. For example, two songs in the opera use the word "nigger". In "As some day it may happen", often called the "list song", Ko-Ko names "the nigger serenader and the others of his race". In the Mikado's song, "A more humane Mikado", the lady who modifies her appearance excessively is to be punished by being "blacked like a nigger with permanent walnut juice".[76] These references are to white performers in blackface minstrel shows, a popular entertainment in the Victorian era, rather than to dark-skinned people.[77] Until well into the 20th century, audiences did not consider the word "nigger" offensive.[78] Audience members objected to the word during the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company's 1948 American tour, however, and Rupert D'Oyly Carte asked A. P. Herbert to supply revised wording. These alterations have been incorporated into the opera's libretto and score since then.[79][n 8]

Also included in the little list song are "the lady novelist" (referring to writers of fluffy romantic novels; these had been lampooned earlier by George Eliot)[80] and "the lady from the provinces who dresses like a guy", where guy refers to the dummy that is part of Guy Fawkes Night, meaning a tasteless woman who dresses like a scarecrow.[81] In the 1908 revival Gilbert allowed substitutions for "the lady novelist".[79][82] To avoid distracting the audience with references that have become offensive over time, lyrics are sometimes modified in modern productions.[83] Changes are also often made, especially in the little list song, to take advantage of opportunities for topical jokes.[84] Richard Suart, a singer well known in the role of Ko-Ko, published a book containing a history of rewrites of the little list song, including many of his own.[85]

Enduring popularity

The Mikado became the most frequently performed Savoy Opera[86] and has been translated into numerous languages. It is one of the most frequently played musical theatre pieces in history.[87] A feature on Chicago Lyric Opera's 2010 production noted that the opera "has been in constant production for the past 125 years", citing its "inherent humor and tunefulness".[44]

The Mikado has been admired by other composers. Dame Ethel Smyth wrote of Sullivan, "One day he presented me with a copy of the full score of The Golden Legend, adding: 'I think this is the best thing I've done, don't you?' and when truth compelled me to say that in my opinion The Mikado is his masterpiece, he cried out: 'O you wretch!' But though he laughed, I could see he was disappointed."[88]

Historical casting

The following tables show the casts of the principal original productions and D'Oyly Carte Opera Company touring repertory at various times through to the company's 1982 closure:

| Role | Savoy Theatre 1885[89] | Fifth Avenue 1885[90][n 9] | Savoy Theatre 1888[91] | Savoy Theatre 1895[92] | Savoy Theatre 1908[93] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Mikado | Richard Temple | Frederick Federici | Richard Temple | R. Scott Fishe² | Henry Lytton |

| Nanki-Poo | Durward Lely | Courtice Pounds | J. G. Robertson | Charles Kenningham | Strafford Moss |

| Ko-Ko | George Grossmith | George Thorne | George Grossmith | Walter Passmore | Charles H. Workman |

| Pooh-Bah | Rutland Barrington | Fred Billington | Rutland Barrington | Rutland Barrington | Rutland Barrington |

| Pish-Tush | Frederick Bovill | Charles Richards[94] | Richard Cummings | Jones Hewson | Leicester Tunks |

| Go-To1 | Rudolph Lewis | R. H. Edgar | Rudolph Lewis | Fred Drawater | |

| Yum-Yum | Leonora Braham | Geraldine Ulmar | Geraldine Ulmar | Florence Perry | Clara Dow |

| Pitti-Sing | Jessie Bond | Kate Forster | Jessie Bond | Jessie Bond | Jessie Rose |

| Peep-Bo | Sybil Grey | Geraldine St. Maur | Sybil Grey | Emmie Owen | Beatrice Boarer |

| Katisha | Rosina Brandram | Elsie Cameron | Rosina Brandram | Rosina Brandram | Louie René |

1Role of Go-To added from April 1885

²For 1896–97 revival, Richard Temple returned to play The Mikado during January–February 1896, and again from November 1896 – February 1897.

| Role | D'Oyly Carte 1915 Tour[95] | D'Oyly Carte 1925 Tour[96] | D'Oyly Carte 1935 Tour[97] | D'Oyly Carte 1945 Tour[98] | D'Oyly Carte 1951 Tour[99] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Mikado | Leicester Tunks | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt |

| Nanki-Poo | Dewey Gibson | Charles Goulding | Charles Goulding | John Dean | Neville Griffiths |

| Ko-Ko | Henry Lytton | Henry Lytton | Martyn Green | Grahame Clifford | Martyn Green |

| Pooh-Bah | Fred Billington | Leo Sheffield | Sydney Granville | Richard Walker | Richard Watson |

| Pish-Tush | Frederick Hobbs | Henry Millidge | Leslie Rands | Wynn Dyson | Alan Styler |

| Go-To | T. Penry Hughes | L. Radley Flynn | L. Radley Flynn | Donald Harris | |

| Yum-Yum | Elsie McDermid | Elsie Griffin | Kathleen Frances | Helen Roberts | Margaret Mitchell |

| Pitti-Sing | Nellie Briercliffe | Aileen Davies | Marjorie Eyre | Marjorie Eyre | Joan Gillingham |

| Peep-Bo | Betty Grylls | Beatrice Elburn | Elizabeth Nickell-Lean | June Field | Joyce Wright |

| Katisha | Bertha Lewis | Bertha Lewis | Dorothy Gill | Ella Halman | Ella Halman |

| Role | D'Oyly Carte 1955 Tour[100] | D'Oyly Carte 1965 Tour[101] | D'Oyly Carte 1975 Tour[102] | D'Oyly Carte 1982 Tour[103] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Mikado | Donald Adams | Donald Adams | John Ayldon | John Ayldon |

| Nanki-Poo | Neville Griffiths | Philip Potter | Colin Wright | Geoffrey Shovelton |

| Ko-Ko | Peter Pratt | John Reed | John Reed | James Conroy-Ward |

| Pooh-Bah | Fisher Morgan | Kenneth Sandford | Kenneth Sandford | Kenneth Sandford |

| Pish-Tush | Jeffrey Skitch | Thomas Lawlor | Michael Rayner | Peter Lyon |

| Go-To | John Banks | George Cook | John Broad | Thomas Scholey |

| Yum-Yum | Cynthia Morey[104] | Valerie Masterson | Julia Goss | Vivian Tierney |

| Pitti-Sing | Joyce Wright | Peggy Ann Jones | Judi Merri | Lorraine Daniels |

| Peep-Bo | Beryl Dixon | Pauline Wales | Patricia Leonard | Roberta Morrell |

| Katisha | Ann Drummond-Grant | Christene Palmer | Lyndsie Holland | Patricia Leonard |

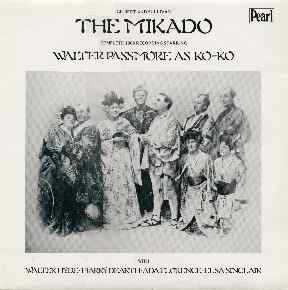

Recordings

Audio recordings

The Mikado has been recorded more often than any other Gilbert and Sullivan opera.[105] Of those by the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, the 1926 recording is the best regarded. Of the modern recordings, the 1992 Mackerras/Telarc is admired.[105]

- Selected audio recordings

- 1926 D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: Harry Norris[106]

- 1936 D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[107]

- 1950 D'Oyly Carte – New Promenade Orchestra, Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[108]

- 1957 D'Oyly Carte – New Symphony Orchestra of London, Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[109]

- 1984 Stratford Festival – Conductor: Berthold Carrière[110]

- 1990 New D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: John Pryce-Jones[111]

- 1992 Mackerras/Telarc – Orchestra & Chorus of the Welsh National Opera, Conductor: Sir Charles Mackerras[112]

Films and videos

Sound film versions of twelve of the musical numbers from The Mikado were produced in Britain, and presented as programs titled Highlights from The Mikado. The first production was released in 1906 by Gaumont Film Company. The second production was released in July 1907 by the Walturdaw Company and starred George Thorne as Ko-Ko. Both of these programs used the Cinematophone sound-on-disc system of phonograph recordings (Phonoscène) of the performers played back along with the silent footage of the performance.[113]

In 1926, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company made a brief promotional film of excerpts from The Mikado. Some of the most famous Savoyards are seen in this film, including Darrell Fancourt as The Mikado, Henry Lytton as Ko-Ko, Leo Sheffield as Pooh-Bah, Elsie Griffin as Yum-Yum, and Bertha Lewis as Katisha.[114][n 10][115]

In 1939, Universal Pictures released a ninety-minute film adaptation of The Mikado. Made in Technicolor, the film stars Martyn Green as Ko-Ko, Sydney Granville as Pooh-Bah, the American singer Kenny Baker as Nanki-Poo and Jean Colin as Yum-Yum. Many of the other leads and choristers were or had been members of the D'Oyly Carte company. The music was conducted by Geoffrey Toye, a former D'Oyly Carte music director, who was also the producer and was credited with the adaptation, which involved a number of cuts, additions and re-ordered scenes. Victor Schertzinger directed, and William V. Skall received an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography.[116][117] Art direction and costume designs were by Marcel Vertès.[118] There were some revisions – The Sun Whose Rays Are All Ablaze is performed twice, first by Nanki-Poo in a new early scene in which he serenades Yum-Yum at her window, and later in the traditional spot. A new prologue which showed Nanki-Poo fleeing in disguise was also added, and much of the Act II music was cut.

In 1966, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company made a film version of The Mikado that closely reflected their traditional staging, although there are some minor cuts. It was filmed on enlarged stage sets rather than on location, much like the 1965 Laurence Olivier Othello, and was directed by the same director, Stuart Burge. It stars John Reed, Kenneth Sandford, Valerie Masterson, Philip Potter, Donald Adams, Christene Palmer and Peggy Ann Jones and was conducted by Isidore Godfrey.[119] The New York Times criticised the filming technique and the orchestra and noted, "Knowing how fine this cast can be in its proper medium, one regrets the impression this Mikado will make on those not fortunate enough to have watched the company in the flesh. The cameras have captured everything about the company's acting except its magic."[120]

Video recordings of The Mikado include a 1972 offering from Gilbert and Sullivan for All; the 1982 Brent-Walker film;[121] the well-regarded 1984 Stratford Festival video; and the 1986 English National Opera production (abridged). Opera Australia have released videos of their 1987 and 2011 productions.[105] Since the 1990s, several professional productions have been recorded on video by the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival.[122]

Other adaptations

The Mikado was adapted as a children's book by W. S. Gilbert titled The Story of The Mikado, which was Gilbert's last literary work.[123] It is a retelling of The Mikado with various changes to simplify language or make it more suitable for children. For example, in the "little list" song, the phrase "society offenders" is changed to "inconvenient people", and the second verse is largely rewritten.

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company controlled the copyrights to performances of The Mikado and the other Gilbert and Sullivan operas in the U.K. until 1961. It usually required authorised productions to present the music and libretto exactly as shown in the copyrighted editions. Since 1961, Gilbert and Sullivan works have been in the public domain and frequently are adapted and performed in new ways.[124] Notable adaptations have included the following:

- Mikado March (1885) by John Philip Sousa[125]

- The Jazz Mikado (1927, Berlin)[126]

- The Swing Mikado was an adaptation of The Mikado with an all-black cast, using swing music, that premiered in Chicago in 1938.

- The Hot Mikado (1939) was a Broadway adaptation of The Mikado with an all-black cast, using jazz and swing music.

- The Bell Telephone Hour version (1960) featured Groucho Marx as Ko-Ko, Stanley Holloway as Pooh-Bah, and Helen Traubel as Katisha. It was directed by Martyn Green.

- The Cool Mikado is a 1962 British musical film directed by Michael Winner that adapts The Mikado in 1960s pop music style and reset as a comic Japanese gangster story.

- The Black Mikado (1975) was a jazzy, sexy production set on a Caribbean island.[127]

- The Chichibu production of The Mikado by the "Tokyo Theatre Company"[66]

- Metropolitan Mikado, a political satire adapted by Ned Sherrin and Alistair Beaton, first performed at Queen Elizabeth Hall (1985) starring Louise Gold, Simon Butteriss, Rosemary Ashe, Robert Meadmore and Martin Smith, produced by Raymond Gubbay.[128]

- Hot Mikado (1986) is a jazz and swing style adaptation that premiered in Washington, D.C. and has been played frequently since then.

- Essgee Entertainment produced an adapted version of The Mikado in 1995 in Australia and New Zealand.[129]

In popular culture

A wide variety of popular media, including films, television, theatre, and advertising have referred to, parodied or pastiched The Mikado or its songs, and phrases from the libretto have entered popular usage in the English language.[130] Some of the best-known of these cultural influences are described below.

Quotes from The Mikado were used in letters to the police by the Zodiac Killer, who murdered at least five people in the San Francisco Bay area between 1966 and 1970. A second-season (1998) episode of the TV show Millennium, titled "The Mikado", is based on the Zodiac case.[131] The Mikado is parodied in Sumo of the Opera, which credits Sullivan as the composer of most of its songs.[132] The detective novel Death at the Opera (1934) by Gladys Mitchell is set against a background of a production of The Mikado.[133] In 2007, the Asian American theatre company, Lodestone Theatre Ensemble, produced The Mikado Project, an original play by Doris Baizley and Ken Narasaki. It was a deconstruction of the opera premised on a fictional Asian American theatre company attempting to raise funds, while grappling with perceived racism in productions of The Mikado, by producing a revisionist version of the opera.[134] This was adapted as a film in 2010.[135]

Film and television references to The Mikado include the climax of the 1978 film Foul Play, which takes place during a performance of The Mikado. In the 2010 episode "Robots Versus Wrestlers" of the TV sitcom How I Met Your Mother, at a high-society party, Marshall strikes an antique Chinese gong. The host rebukes him: "Young man, that gong is a 500-year-old relic that hasn't been struck since W. S. Gilbert hit it at the London premiere of The Mikado in 1885!" Marshall quips, "His wife's a 500-year-old relic that hasn't been struck since W. S. Gilbert hit it at the London premiere".[136]

Beginning in the 1880s, Mikado trading cards were created that advertised various products.[137] "The Mikado" is a villainous vigilante in the comic book superhero series The Question, by Denny O'Neil and Denys Cowan. He dons a Japanese mask and kills malefactors in appropriate ways – letting "the punishment fit the crime".[138] In 1888, Ed J. Smith wrote a stage parody of The Mikado called The Capitalist; or, The City of Fort Worth to encourage capital investment in Fort Worth, Texas.[139] The 2-8-2 railroad locomotive was renamed "The Mikado" when a U.S. production run of these locomotives was shipped to Japan in 1893.

Popular phrases from The Mikado

The phrase "A short, sharp shock", from the Act 1 song "I am so proud" has entered the English language, appearing in titles of books and songs, such as in samples of Pink Floyd's "The Dark Side of the Moon", as well as political manifestos. Likewise "Let the punishment fit the crime" is an often-used phrase from the Mikado's Act II song and has been mentioned in the course of British political debates, though the concept predates Gilbert.[140][141] For instance, episode 80 of the television series Magnum, P.I., "Let the Punishment Fit the Crime", features bits of several songs from The Mikado.[142] The phrase and the Mikado's song also are featured in the Dad's Army episode "A Soldier's Farewell." In The Parent Trap (1961), the camp director quotes the phrase before sentencing the twins to the isolation cabin together.

The name of the character Pooh-Bah has entered the English language to mean a person who holds many titles, often a pompous or self-important person.[143][144] Pooh-Bah is mentioned in P. G. Wodehouse's novel Something Fresh and in other, often political, contexts.[n 11] In December 2009 BBC presenter James Naughtie, on Radio 4's Today programme, compared UK cabinet member Peter Mandelson to Pooh-Bah because Mandelson held many offices of state, including Secretary of State for Business, First Secretary of State, Lord President of the Council, President of the Board of Trade, and Church Commissioner, and he sat on 35 cabinet committees and subcommittees. Mandelson replied, "Who is Pooh-Bah?" Mandelson was also described as "the grand Pooh-Bah of British politics" earlier the same week by the theatre critic Charles Spencer of The Daily Telegraph.[145] In the U.S., particularly, the term has come to describe, mockingly, people who hold impressive titles but whose authority is limited.[146] William Safire speculated that invention of Winnie-the-Pooh by the author A. A. Milne might have been influenced by the character.[144] The term "Grand Poobah" has been used on television shows, including The Flintstones and Happy Days, and in other media, as the title of a high-ranking official in a men's club, spoofing clubs like the Freemasons, the Shriners, and the Elks Club.[147]

References to songs in The Mikado

Politicians often use phrases from songs in The Mikado. For example, Conservative Peter Lilley pastiched "As Someday It May Happen" to specify some groups to whom he objected, including "sponging socialists" and "young ladies who get pregnant just to jump the housing queue".[140] Comedian Allan Sherman also did a variant on the "Little List" song, presenting reasons one might want to seek psychiatric help, titled "You Need an Analyst".[148] In a Eureeka's Castle Christmas special called "Just Put it on the List," the twins, Bogg and Quagmire, describe what they'd like for Christmas to the tune of the song. Richard Suart and A.S.H. Smyth released a book in 2008 called They'd none of 'em be missed, about the history of The Mikado and the 20 years of little list parodies by Suart, the English National Opera's usual Ko-Ko.[149] In Isaac Asimov's short story "Runaround" a robot recites some of the song.[130]

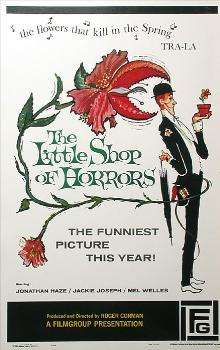

Other songs in The Mikado have been referenced in films, television and other media. For example, the movie poster for The Little Shop of Horrors, shown to the left, parodies the song title "The Flowers that Bloom in the Spring, Tra la!", changing the word "bloom" to "kill".[150] In The Producers, an auditioner for the musical Springtime for Hitler begins his audition with Nanki-Poo's song, "A wand'ring minstrel I." He is quickly dismissed. In the 2006 film Brick, femme fatale Laura (Nora Zehetner) performs a spoken-word version of "The Sun Whose Rays are All Ablaze" while playing piano. In the 1966 Batman episode "The Minstrel's Shakedown," the villain identifies himself as "The Minstrel" by singing to the tune of "A wand'ring minstrel I." In the Top Cat episode "All That Jazz", Officer Dibble woefully sings the same song. In Blackadder Goes Forth a recording of "A Wand'ring Minstrel I" is played on a gramophone at the beginning of the first episode, and a snatch of the song is also sung by Captain Blackadder in the episode involving "Speckled Jim". "There Is Beauty in the Bellow of the Blast" is performed by Richard Thompson and Judith Owen on the album 1000 Years of Popular Music.[151]

The song "Three Little Maids" is featured in the 1981 film Chariots of Fire, where Harold Abrahams first sees his future wife dressed as one of the Three Little Maids. Television programmes that have featured the song include the Cheers episode "Simon Says" (for which John Cleese won an Emmy Award), the Frasier episode "Leapin' Lizards", the Angel episode "Hole in the World", The Simpsons episode "Cape Feare",[152] The Suite Life of Zack & Cody episode "Lost in Translation," and The Animaniacs Vol. 1 episode "Hello Nice Warners". The Capitol Steps performed a parody titled "Three Little Kurds from School Are We". On the Dinah Shore Show, Shore sang the song with Joan Sutherland and Ella Fitzgerald in 1963.[153]

References to "Tit-Willow" ("On a tree by a river") have included Allan Sherman's comedy song "The Bronx Bird Watcher", about a Yiddish-accented bird whose beautiful singing leads to a sad end.[154] On The Dick Cavett Show, Groucho Marx and Cavett sang the song. Groucho interrupted the song to quiz the audience on the meaning of the word "obdurate". A Season 1 episode of The Muppet Show (aired on 22 November 1976) featured Rowlf the Dog and Sam Eagle singing the song, with Sam clearly embarrassed at having to sing the word 'tit' (also asking the meaning of "obdurate"). In the film Whoever Slew Auntie Roo?, Shelley Winters as the title character sings the song just before she is murdered.[155]

See also

- British-Japanese relations

- Cultural influence of Gilbert and Sullivan

- Topsy-Turvy, a 1999 musical drama film about the creation of the piece

Notes and references

Notes

- The longest-running piece of musical theatre was the operetta Les Cloches de Corneville, which held the title until Dorothy opened in 1886, which pushed The Mikado down to third place.

- The actor who originally played Pish-Tush proved unable satisfactorily to sing the low notes in the Act Two quartet, "Brightly dawns our wedding day". The Pish-Tush line in this quartet lies lower than the rest of the role and ends on a bottom F. Therefore, an extra bass character, called Go-To, was introduced for this song and the dialogue scene leading into it. The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company continued generally to bifurcate the role, but vocal scores generally do not mention it. Other companies, however, have generally eliminated the role of Go-To and restored the material to Pish-Tush, when the role is played by someone with a sufficient vocal range.

- This was a topical British legal joke: In the 1882 court case of Walsh v. Lonsdale, 21 ChD 9, it was held that, as equity regards as done those things that ought to have been done, an agreement for a lease is as good as a lease. See Lord Neuberger's 2011 Bentham lecture "Swindlers (including the Master of the Rolls?) Not Wanted: Bentham and Justice Reform" Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, UCL Bentham Association, 2 March 2011

- The original version of this number included Pish-Tush. His part in it was first reduced, and then eliminated. However, some vocal scores still include Pish-Tush in this number in his reduced role.

- This character is derived from James Planché's Baron Factotum, the "Great-Grand-Lord-High-Everything" in The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood (1840). Williams (2010), p. 267

- A character in the Bab Ballad "King Borriah Bungalee Boo" (1866) is the haughty "Pish-Tush-Pooh-Bah", which is split into two in The Mikado – the terms pish, tush, pooh, and bah are all expressions of contempt.

- The ban forced Helen Carte to drop the always-profitable show from her Gilbert and Sullivan repertory season. See Wilson and Lloyd, p. 83

- In Ko-ko's song the nigger serenader became "the banjo serenader" (Dover, p. 9; and Green, p. 416) and the Mikado's punishment for the lady was to be "painted with vigour" (Bradley (1996) p. 623; and Green p. 435).

- The production later moved to the Standard Theatre.

- The first phonoscènes in the UK were presented at Buckingham Palace in 1907 and included Tit-Willow, sung by George Thorne.

- Another such example is R. A. Butler's biography, in which there is a chapter called "The Pooh-Bah Years," when Butler held multiple cabinet portfolios.

References

- Gillan, Don. Longest runs in the theatre up to 1920. Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Mencken, H. L. Article on The Mikado Archived 24 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Baltimore Evening Sun, 29 November 1910

- Traubner, p. 162

- Jacobs, p. 187

- Crowther, Andrew. "The Carpet Quarrel Explained" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 28 June 1997, accessed 6 November 2007

- Ainger, p. 226

- Ainger, p. 230

- Ainger, p. 232

- Ainger, p. 233

- "The Japanese exhibition, 1885–87", English Heritage, accessed 29 January 2013

- Cellier and Bridgeman, p. 186

- Jones (1985), p. 22

- Jones (2007), p. 687

- Jones (1985), p. 25

- Baily, pp. 235–36

- Schickel, Richard (27 December 1999). "Topsy-Turvy". Time. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Jones (2007), pp. 688–93

- Quoted at Lyricoperasandiego.com

- Gilbert, W. S. "The Evolution of The Mikado", New York Daily Tribune, 9 August 1885

- Illustrated London News, 12 February 1885, p. 143

- Hughes, pp. 131–32

- Seeley, Paul. (1985) "The Japanese March in The Mikado", The Musical Times, 126(1710) pp. 454–56.

- Gillan, Don. A History of the Royal Command Performance, StageBeauty.net, accessed 16 June 2009

- Rollins and Witts, Appendix, p. VIII

- Cellier and Bridgeman, p. 192

- Rollins and Witts, passim

- Photos of, and information about, the 1926 Mikado costume designs. Archived 22 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Prestige, Colin. "D'Oyly Carte and the Pirates", a paper presented at the International Conference of G&S held at the University of Kansas, May 1970

- Information about American productions Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte had tried various techniques for gaining an American copyright that would prevent unauthorised productions. In the case of Princess Ida and The Mikado, they hired an American, George Lowell Tracy, to create the piano arrangement of the score, hoping that he would obtain rights that he could assign to them. The U.S. courts held, however, that the act of publication made the opera freely available for production by anyone. Jacobs, p. 214 and Ainger, pp. 247, 248 and 251

- Rollins and Witts, p. 59

- Rollins and Witts, pp. 59–64

- Jacobs, Arthur. "Carte, Richard D'Oyly (1844–1901)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004, accessed 12 September 2008

- Joseph (1994), pp. 81 and 163

- Bradley (2005), p. 25

- Jellinek, Hedy and George. "The One World of Gilbert and Sullivan", Saturday Review, 26 October 1968, pp. 69–72 and 94

- The conductor Ernest MacMillan, along with other musician internees, recreated the score from memory with the aid of a libretto. See MacMillan, pp. 25–27

- Hall, George. "The Mikado review at London Coliseum – 'still delivers the goods'", The Stage, 23 November 2015

- "Production History", Stratford Festival website, accessed 15 February 2014

- Beatty-Kingston, William. The Theatre, 1 April 1885, quoted in Fitzgerald, pp. 165–66

- Kan'ichi Asakawa. "Institutions before the Reform", The Early Institutional Life of Japan: A Study in the Reform of 645 A.D., Tokyo: Shueisha (1903), p. 25. Quote: "We purposely avoid, in spite of its wide usage in foreign literature, the misleading term Mikado. ... It originally meant not only the Sovereign, but also his house, the court, and even the State, and its use in historical writings causes many difficulties. ... The native Japanese employ the term neither in speech nor in writing."

- Dark and Grey, p. 101

- Mairs, Dave. "Gilbert & Sullivan... the greatest show takes to the road" Archived 26 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Your Canterbury, 2 June 2014

- Steinberg, Neil. "Updated Mikado promises to be as rousing as ever". Chicago Sun-Times, 6 December 2010.

- "Mikado Genesis", Lyric Opera San Diego

- Jones (1985), pp. 22–25

- Herr, K. T. "Local production of The Mikado raises questions on theatre and race", The Rapidian, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 22 April 2016

- Allen, p. 239

- this translation. Daniel Kravetz wrote in The Palace Peeper, December 2007, p. 3, that the song was composed in 1868 by Masujiro Omura, with words by Yajiro Shinagawa.

- "Historia Miya San" Archived 5 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. General Sasaki gives historical information about "Ton-yare Bushi" and includes Midi files and a translation. Here is a YouTube version of the Japanese song.

- "A Study Guide to the production of The Mikado", Pittsburgh Public Theater, p. 13

- Munich, Adrienne. Queen Victoria's Secrets, 1998, ISBN 978-0-231-10481-4

- Seay, James L. "For Tricks that Are Dark", Pamphlet Press

- Faris, p. 53

- Review of The Mikado discussing reception by the Japanese

- "Edward Gorey in Japan; Translation or Transformation: A Chat with Motoyuki Shibata", Goreyography (2008)

- "London Greets Fushimi; He Visits King Edward – Wants to Hear "The Mikado"", The New York Times, 7 May 1907

- Andrew, Goodman (1980). "The Fushimi incident: theatre censorship and The Mikado". Journal of Legal History. 1 (3): 297–302. doi:10.1080/01440368008530722. Cass; Routledge

- Adair Fitz-Gerald, S. J. (1925). The Story of the Savoy Opera in Gilbert and Sullivan's Day. D. Appleton and Company. p. 212.

- Article about the 1946 Mikado in Japan; "GIs play Mikado in Tokyo", Life magazine, 9 September 1946, vol. 21, pp. 42–43

- "Japan: No Mikado, Much Regret", Time Magazine, 16 June 1947

- "Ernie Pyle Theater Tokyo presents Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado", Japan Times, 5 February 1970

- Sumiko Enbutsu: The Mikado in the Town of Chichibu

- Brooke, James. "Japanese Hail The Mikado, Long-Banned Imperial Spoof", The New York Times, 3 April 2003, accessed 15 July 2014

- "The Mikado – Diary". The Times, 23 July 1992

- Sean Curtin. The Chichibu Mikado Archived 22 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Japan Society.

- Kai-Hwa Wang, Frances. "Stereotypes in The Mikado Stir Controversy in Seattle", NBC news, 17 July 2014

- "History of Yellowface: The Mikado", Asian American Theatre Review, accessed July 13, 2019

- Crowther, Andrew. "The Mikado and Racism", Andrew Crowther: Playwright and Biographer, 20 July 2014

- Levin, Michael. "Who the Hell Put These People in Charge of Popular Culture?", Huffington Post, 16 August 2014

- Kiley, Brendan. "Last Night's Polite But Necessary Discussion at the Seattle Rep About Race, Theater, and the Mikado Controversy", TheStranger.com, 19 August 2014

- Nguyen, Michael D. "New York City Production of 'The Mikado' Canceled Following Accusations of Racism", NBC News, 18 September 2015

- Fonseca-Wollheim, Corinna da. "Is The Mikado Too Politically Incorrect to Be Fixed? Maybe Not.", 30 December 2016; and "New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players Reveals Concepts for Reimagined The Mikado; Kelvin Moon Loh Joins Creative Team!", BroadwayWorld.com, 6 October 2016

- Tran, Diep. "Building a Better Mikado, Minus the Yellowface", American Theatre, 20 April 2016

- Kosman, Joshua. "Lamplighters' transplanted Mikado retains its charm", San Francisco Chronicle, 8 August 2016; and Hurwitt, Sam. "Review: Guilt-free Mikado unveiled by Lamplighters", The Mercury News, 8 August 2016

- Gilbert (1992) p. 41, note 1

- Gilbert (1992), p. 9, note 1

- Pullum, Geoffrey. "The Politics of Taboo Words" Archived 20 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 19 May 2014

- Bradley (1996) p. 572.

- Eliot, George. "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists" (1896).

- Benford, Chapter IX

- Baily, Lesley. Gilbert and Sullivan and their world (1973), Thames and Hudson, p. 117

- Rahim, Sameer. "The opera novice: The Mikado by Gilbert & Sullivan", The Telegraph, 1 February 2013, accessed 13 May 2014; Tommasini, Anthony. "Mikado Survives Some Updating", The New York Times, 10 January 1998, accessed 20 May 2014

- The Independent review of 2004 London Mikado

- Suart, Richard. They'd None of 'em Be Missed. Pallas Athene Arts, 2008 ISBN 978-1-84368-036-9

- Wilson and Lloyd, p. 37

- See here Archived 5 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine and here

- Smythe, Dame Ethel. Impressions that Remained, 1923, Quoted in Baily, p. 292

- Rollins and Witts, p. 10

- Gänzl, p. 275.

- Rollins and Witts, p. 11

- Rollins and Witts, p. 15

- Rollins and Witts, p. 22

- George Byron Browne later in the run

- Rollins and Witts, p. 132

- Rollins and Witts, p. 148

- Rollins and Witts, p. 160

- Rollins and Witts, p. 170

- Rollins and Witts, p. 176

- Rollins and Witts, p. 180

- Rollins and Witts, 1st Supplement, p. 7

- Rollins and Witts, 3rd Supplement, p. 28

- Rollins and Witts, 4th Supplement, p. 42

- Morey is President of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society in London. See also Ffrench, Andrew. "Retired opera singer Cynthia Morey lands 'yum' film role in Quartet", Oxford Mail, 2 February 2013

- Shepherd, Marc. "Recordings of The Mikado", Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 13 July 2009, accessed 6 June 2012

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1926 recording Archived 26 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 24 December 2003, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1936 recording Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 11 May 2003, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1950 recording Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 11 July 2009, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1957 recording Archived 1 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 8 July 2005, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1984 Stratford recording Archived 31 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 24 October 2001, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1990 recording Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 12 July 2009, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. Review of the 1992 recording Archived 3 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 12 July 2009, accessed 31 July 2016

- Altman, Rick. Silent Film Sound, Columbia University Press (2005), p. 159, ISBN 978-0-231-11662-6

- Shepherd, Marc. "The 1926 D'Oyly Carte Mikado Film" Archived 24 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 15 April 2009, accessed 31 July 2016

- Schmitt, Thomas. The Genealogy of Clip Culture, in Henry Keazor and Thorsten Wübbena (eds.) Rewind, Play, Fast Forward: The Past, Present and Future of the Music Video, transcript Verlag (2010), pp. 45 et seq., ISBN 978-3-8376-1185-4

- "The Mikado Archived 20 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Cinegram No. 75, Pilot Press, London (souvenir programme), The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 1938, accessed 31 July 2016

- Shepherd, Marc. "The Technicolor Mikado Film (1939)" Archived 2 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 28 June 2009, accessed 31 July 2016

- Galbraith IV, Stuart. "The Mikado (Blu-ray)", DVDTalk, 27 March 2011

- Photos from the 1966 film

- Sullivan, Dan. "The Mikado (1967)", The New York Times, 15 March 1967, accessed 22 March 2010

- According to discographer Marc Shepherd, The Mikado is one of the weakest in the Brent Walker series. See Shepherd, Marc. "The Brent Walker Mikado (1982)" Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 5 April 2009

- "Professional Shows from the Festival" Archived 26 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Musical Collectibles catalogue website, accessed 15 October 2012

- Gilbert (1921), preface by Rupert D'Oyly Carte, p. vii: "But the evidence of never-failing popularity which recent revivals of the Savoy Operas have afforded suggests that this last literary work of Sir W. S. Gilbert should no longer be withheld [due to wartime shortages] from the public".

- Fishman, Stephen. The Public Domain: How to Find Copyright-Free Writings, Music, Art & More, Ch. 1, § A.4.a, Nolo Press, 3rd ed, 2006.

- Bierley, Paul E. The Works of John Philip Sousa, Integrity Press, Westerville, Ohio (1984), p. 71

- "Notable Gilbert & Sullivan adaptations", Grim's Dyke Hotel, 29 December 2016

- The Black Mikado Archived 26 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography, 25 November 2001, accessed 31 July 2016

- Walsh, Maeve. "Theatre: It Was 15 Years Ago Today; The great Ned and Ken show", The Independent, 25 July 1999

- Information about Essgee's Mikado

- "Gilbert & Sullivan in Popular Culture: The Mikado", The Gilbert & Sullivan Very Light Opera Company, accessed 11 June 2017

- "Millennium Episode Profile of 'The Mikado'". Millennium-This Is Who We Are, Graham P. Smith, accessed 16 August 2010

- Shulgasser-Parker, Barbara. "VeggieTales: 'Sumo of the Opera'" Archived 12 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Common Sense Media, accessed 12 June 2020

- Mitchell, Gladys. Death at the Opera, Grayson & Grayson (London: 1934)

- The Mikado Project Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, LodestoneTheatre.org, accessed 2 October 2010

- Heymont, George. "The Mikado Project (Trouble In Titipu)", The Huffington Post, 21 April 2011, accessed 14 March 2012

- Bowman, Donna. "How I Met Your Mother 'Robots Vs. Wrestlers'", The A.V. Club, Onion, Inc., 10 May 2010, accessed 19 June 2016

- "Mikado-themed advertising cards". The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008.

- Who's Who in the DC Universe, update 1987, vol. 4, p. 8

- Smith, Ed. "The Capitalist; or, The City of Fort Worth (The Texas Mikado)", Baylor University Libraries Digital Collections, accessed 9 November 2012

- Green, Edward. "Ballads,songs and speeches", BBC News, 20 September 2004, accessed 30 September 2009

- Keith Wiley webpage, referring to the Code of Hammurabi

- See Wikipedia List of Magnum, P.I. episodes and TV.com Magnum, P.I. Episode Guide

- "Pooh Bah", Oxford English Dictionary, accessed 7 December 2009 (subscription required)

- Safire, William. "Whence Poo-Bah", GASBAG, vol. 24, no. 3, issue 186, January/February 1993, p. 28.

- Beckford, Martin. "Lord Mandelson likened to Pooh-Bah, Lord High Everything Else in The Mikado", The Daily Telegraph, 3 December 2009

- "pooh-bah – Definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- "Loyal Order of Water Buffaloes" Archived 15 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Grand Lodge Freemasonry site, 8 April 2004, accessed 14 September 2009. See also "The Grand Poo-Bah". The KoL Wiki. Coldfront L.L.C. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- Sherman, Allan. Allan in Wonderland (1964) Warner Bros. Records

- Suart, Richard and Smyth, A.S.H. They’d none of ‘em be missed, (2008) Pallas Athene. ISBN 978-1-84368-036-9.

- Stone, Martin. "Little Shop of Horrors – Screen to Stage". Mondo Musicals! 14 February 2008, accessed 6 April 2010; and Bord, Chris. "The Atlantic.com article on the Mikado", Earlville Opera House, 9 August 2014, accessed 31 January 2016

- "Song-o-matic – There is Beauty". BeesWeb – the official site of Richard Thompson. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Jean, Al. (2004). Commentary for "Cape Feare", in The Simpsons: The Complete Fifth Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox

- "The Dinah Shore Chevy Show, March 17, 1963 (Season 7, episode 7)", TV.com, accessed 21 April 2012

- Sherman, Allan. My Son, the Celebrity (1963) Warner Bros. Records

- Shimon, Darius Drewe. "Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (1971)" Archived 9 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Britmovie.co.uk, 21 December 2009

Sources

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan, a Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Allen, Reginald (1975). The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan. London: Chappell & Co. Ltd.

- Baily, Leslie (1952). The Gilbert & Sullivan Book. London: Cassell & Company Ltd.

- Benford, Harry (1999). The Gilbert & Sullivan Lexicon, 3rd Revised Edition. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Queensbury Press. ISBN 978-0-9667916-1-7.

- Bradley, Ian (1996). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press.

- Bradley, Ian (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516700-7.

- Cellier, François; Cunningham Bridgeman (1914). Gilbert, Sullivan, and D'Oyly Carte. London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons.

- Dark, Sidney; Rowland Grey (1923). W. S. Gilbert: His Life and Letters. Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Fink, Robert. "Rhythm and Text Setting in The Mikado", 19th Century Music, vol. XIV No. 1, Summer 1990

- Fitzgerald, Percy Hetherington (1899). The Savoy Opera and the Savoyards. London: Chatto & Windus. This book is available online at Internet Archive. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- Gänzl, Kurt (1995). Gänzl's Book of the Broadway Musical: 75 Favorite Shows, from H.M.S. Pinafore to Sunset Boulevard. Schirmer. ISBN 0-02-870832-6.

- Gilbert, W. S. (1921). The Story of the Mikado. London: Daniel O'Connor, 90 Great Russell Street.

- Gilbert, William Schwenck (1992). Philip Smith (ed.). The Mikado. Dover. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-486-27268-9.

- Green, Martyn (editor) (1961). Martyn Green's Treasury of Gilbert and Sullivan. Michael Joseph.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Hughes, Gervase (1960). The Music of Arthur Sullivan. London: Macmillan.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1984). Arthur Sullivan: A Victorian Musician. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Brian (Spring 1985). "The sword that never fell". W. S. Gilbert Society Journal. 1 (1): 22–25.

- Jones, Brian (Winter 2007). "Japan in London 1885". W. S. Gilbert Society Journal (22): 686–96.

- Joseph, Tony (1994). D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, 1875–1982: An Unofficial History. London: Bunthorne Books. ISBN 0-9507992-1-1

- Macmillan, Ernest (1997). MacMillan on music: essays on music. London: Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-2857.

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. Also, five supplements, privately printed.

- Seeley, Paul (August 1985). "The Japanese March in 'The Mikado'". The Musical Times. The Musical Times, Vol. 126, No. 1710. 126 (1710): 454–456. doi:10.2307/964306. JSTOR 964306.

- Traubner, Richard (2003). Operetta: a theatrical history (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96641-8.

- Williams, Carolyn (2010). Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14804-7.

- Wilson, Robin; Frederic Lloyd (1984). Gilbert & Sullivan: The Official D'Oyly Carte Picture History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Further reading

- Beckerman, Michael (1989). "The Sword on the Wall: Japanese Elements and Their Significance in 'The Mikado'". The Musical Quarterly. 73 (3): 303–319. doi:10.1093/mq/73.3.303.

- Clements, Jonathan. "Titipu", on the historical background of The Mikado's setting

- Lee, Josephine. The Japan of Pure Invention: Gilbert & Sullivan's 'The Mikado'. University of Minnesota Press, 2010 ISBN 978-0-8166-6580-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Mikado. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Mikado at The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

- Article by H. L. Mencken on the impact of The Mikado (from 1910)

- Discussion of The Mikado from the musicals101 site

- Description of preparations for The Mikado

- Description of production history and modern Australian productions

- Article on the genesis of The Mikado

- The Mikado at The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography

- 1885 review of The Mikado in "The Entr'acte".

- Koko's Korner: A website dedicated almost entirely to the character of Ko-Ko in The Mikado

- List of longest running plays in London and New York

- Biographies of the people listed in the historical casting chart

- Cinegram of the 1938 film of The Mikado

- D'Oyly Carte Prompt Books at The Victoria and Albert Museum

- Page linking to Mikado song parodies

- Theatre posters from performances at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh

- The Story of the Mikado at Faded Page (Canada)