Karamokho Alfa

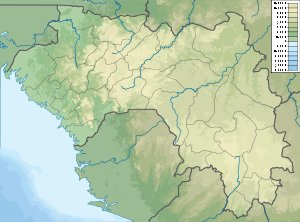

Karamokho Alfa[lower-alpha 1] (born Ibrahima Musa Sambeghu and sometimes called Alfa Ibrahim) (died c. 1751) was a Fula religious leader who led a jihad that created the Imamate of Futa Jallon in what is now Guinea. This was one of the first of the Fulbe jihads that established Muslim states in West Africa.

Karamokho Alfa | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ibrahima Musa Sambeghu |

| Died | c. 1751 |

| Nationality | Fulbe |

| Occupation | Cleric |

| Known for | Founder of the Imamate of Futa Jallon |

Alfa Ba, Karamoko Alfa's father, formed a coalition of Muslim Fulbe and called for the jihad in 1725, but died before the struggle began. The jihad was launched around 1726-1727. After a crucial, concluding victory at Talansan, the state was established at a meeting of nine Fulbe ulama who each represented one of the Futa Jallon provinces. Ibrahima Sambeghu, who became known as Karamokho Alfa, was the hereditary ruler of Timbo and one of the nine ulama. He was elected leader of the jihad. Under his leadership, Futa Jallon became the first Muslim state to be founded by the Fulbe. Despite this, Karamokho Alfa was constrained by the other eight ulama. Some of the other Ulama had more secular power than Karamokho Alfa, who directly ruled only the diwal of Timbo; for this reason the new state was always a tenuous confederation. Karamoko Alfa ruled the theocratic state until 1748, when his excessive devotions caused him to become mentally unstable and Sori was selected as de facto leader. Karamokho Alfa died around 1751 and was formally succeeded by Ibrahim Sori, his cousin.

Background

The Futa Jallon is the highland region where the Senegal and Gambia rivers rise.[2][3] In the fifteenth century the valleys were occupied by Mandé peoples - Susu and Yalunka farmers. Around that time, Fulbe herders began moving into the region, grazing their livestock on the plateaux. At first they peacefully accepted a subordinate position to the Susu and Yalunka.[4] The Fulbe and Mandé peoples intermixed to some extent, and the more sedentary of the Fulbe came to look down on their pastoral cousins.[5]

Europeans began to establish trading posts on the upper Guinea coast in the seventeenth century, stimulating a growing trade in hides and slaves. The pastoral Fulbe expanded their herds to meet the demand for hides. They began to compete for land with the agriculturalists, and became interested in the profitable slave trade.[4] They were increasingly influenced by their Muslim trading partners.[6]

In the last quarter of the seventeenth century the Zawāyā reformer Nasir al-Din launched a jihad to restore purity of religious observance in the Futa Toro region to the north. He gained support from the Torodbe clerical clan against the warriors, but by 1677 the movement had been defeated.[6] Some of the Torodbe migrated south to Bundu and some continued on to the Futa Jallon.[7] The Torodbe, the kinsmen of the Fulbe of the Futa Jallon, influenced them in embracing a more militant form of Islam.[4]

Jihad

[8] The jihad was launched around 1726 or 1727.[9] The movement was primarily religious, and its leaders included both Mandé and Fulbe marabouts.[10] The jihad also attracted some formerly non-Muslim Fulbe, who associated it not just with Islam but with freedom of the Fulbe from subordination to the Mandé peoples.[11] It was opposed by other non-Muslim Fulbe and by non-Muslim Yalunka leaders.[10]

According to tradition, Ibrahim Sori symbolically launched the war in 1727 by destroying the great ceremonial drum of the Yalunka people with his sword.[12] The jihadists then won a major victory at Talansan.[13] A force of 99 Muslims defeated a non-Muslim force ten times greater, killing many of their opponents.[14] After this victory the state was established at a meeting of nine Fulbe ulama who each represented one of the Futa Jallon provinces.[11] Ibrahima Sambeghu, who became known as Karamokho Alfa,[lower-alpha 2] was the hereditary ruler of Timbo and one of the nine ulama. He was elected leader of the jihad.[16] He took the title almami, or "the Imam".[17] Under his leadership Futa Jallon became the first Muslim state to be founded by the Fulbe.[8]

Karamoko Alfa managed to enlist disadvantaged groups such as gangs of young men, outlaws and slaves.[18] Karamokho Alfa's maternal cousin was Maka Jiba, the ruler of Bundu, and both men studied in Fugumba under the famous scholar Tierno Samba. However, there are no records of Bundu participation in the Futa Jallon jihad, perhaps because of the internal troubles in Bundu at that time, or perhaps because Maka Jiba was not greatly interested in the cause.[19] Although he was an inspired religious leader, Karamoko Alfa was not qualified as a military leader. Ibrahim Sori took this role.[12] Some of the population resisted conversion for many years, particularly the nomadic Fulbe herders. They rightly feared that the marabouts would abuse their authority.[20]

Ruler

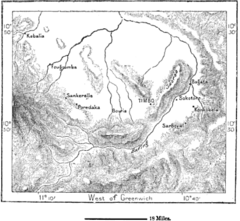

Karamokho Alfa was constrained by the other eight ulama, each of whom ruled their own province, or diwal.[16][lower-alpha 3] The structure of the new Fulbe state had an almami at its head, Karamokho Alfa being the first, with his political capital at Timbo.[21] However, some of the other Ulama had more secular power than Karamokho Alfa, who directly ruled only the diwal of Timbo.[11] The religious capital was at Fugumba, where the council of the alama sat. The council operated as a strong curb on the power of the almami, and the ulama retained much autonomy, so the new state was always a loose federation.[21]

Karamokho Alfa was known for his Islamic scholarship and piety.[22] He respected the rights of the old "masters of the soil", saying "it was Allah who had established them." Despite this ruling, the imams reserved the right to reassign land, since they held it in trust for the people. In effect the existing property owners were not displaced, but now had to pay Zakāt as a form of rent.[23] Karamoko Alfa ruled the theocratic state until 1748, when his excessive devotions caused him to become mentally unstable and Sori was selected as de facto leader.[12]

Legacy

Karamokho Alfa died around 1751 and was formally succeeded by Ibrahim Sori, his cousin.[22][lower-alpha 4] Ibrahim Sori Mawdo was chosen after failure of Alfa Saliu, son of Karamoko Alfa,who was too young.[25] Ibrahim Sori was an aggressive military commander who initiated a series of wars. After many years of conflict, Ibrahim Sori achieved a decisive victory in 1776 that consolidated the power of the Fulbe state. The jihad had achieved its goals and Ibrahim Sori assumed the title of almami.[22]

Under Ibrahima Sori slaves were sold to obtain munitions needed for the wars. This was considered acceptable as long as the slaves were not Muslim.[26] The jihad created a valuable supply of slaves from the defeated peoples that may have provided a motive for further conquests.[4] The Fulbe ruling class became wealthy slave owners and slave traders. Slave villages were founded, whose inhabitants provided food for their Fulba masters to consume or sell. [1] As of 2013 the Fulbe were the largest ethnic group in Guinea at 40% of the population, after the Malinke (30%) and Susu (20%).[27]

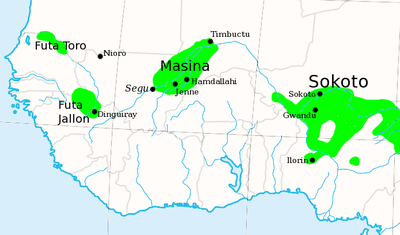

The jihad in Futa Jallon was followed by a jihad in Futa Toro between 1769 and 1776 led by Sileymaani Baal. The largest of the Fulani jihads was led by the scholar Usman dan Fodio and established the Sokoto Caliphate in 1808, stretching across what is now the north of Nigeria. The Fulbe Muslim state of Masina was established to the south of Timbuktu in 1818. [28]

Karamokho Alfa came to be thought of as a saint. A story is told of a miracle that occurred more than a hundred years after his death. The chief of the Ouassoulounké, Kondé Buraima, opened Karamokho Alfa's tomb and cut off the left hand of the body. Blood poured from the severed wrist, causing Kondé Buraima to flee in terror.[29]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- Ibrahima Sambeghu was given the name "Karamokho Alfa" as an adult. "Karamokho" means teacher in the Mandinka language and "Alfa" means teacher in the Fula language.[1]

- The leaders of the Fulbe diwe used the title "Alfa", or "teacher". Karamokho Alfa was the Alfa of the Timbo Diwal.[15]

- The provinces were Labé, Buriya, Timbi, Kebaali, Kollade, Koyin, Fugumba and Fode Haaji.[15]

- Ibrahima Sambeghu's ancestor Mamadou Moktar Bari had two sons. Fode Seri was the ancestor of the Seriyanke of Fougumba, and Fode Seidi was ancestor of the Seidiyanke of Timbo. Fode Seidi's great-grandson Alfa Kikala was the grandfather of both Almami Sory and Karamoko Alfa.[24]

Citations

- Isichei 1997, p. 301.

- Ruthven 2006, p. 264.

- Haggett 2002, p. 2316.

- Gray 1975, p. 207.

- Willis 1979, p. 25.

- Gray 1975, p. 205.

- Gray 1975, p. 206.

- Ndukwe 1996, p. 48.

- Amanat & Bernhardsson 2002, p. 244.

- Ogot 1992, p. 289.

- Gray 1975, p. 208.

- Alford 1977, p. 4.

- Adamu 1988, p. 244.

- Rashedi 2009, p. 38.

- Ogot 1992, p. 291.

- Ogot 2010, p. 346.

- Holt, Lambton & Lewis 1977, p. 365.

- Lapidus 2002, p. 418.

- Gomez 2002, p. 72.

- Ogot 1992, p. 292.

- U.N. Comité de culture 1999, p. 331.

- Gray 1975, p. 209.

- Willis 1979, p. 28.

- Derman & Derman 1973, p. 20.

- Harrison 2003, p. 68.

- Thornton 1998, p. 315-316.

- AFRICA :: GUINEA - CIA.

- Stanton, Ramsamy & Seybolt 2012, p. 148.

- Sanneh 1997, p. 78.

Sources

- Adamu, Mahdi (1988-11-01). Pastoralists of the West African Savanna. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2248-7. Retrieved 2013-02-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "AFRICA :: GUINEA". CIA. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- Alford, Terry (1977). Prince Among Slaves. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-504223-8. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Amanat, Abbas; Bernhardsson, Magnus T. (2002-02-09). Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse from the Ancient Middle East to Modern America. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-724-6. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Derman, William; Derman, Louise (1973). Serfs Peasants Socialst. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01728-3. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gomez, Michael A. (2002-07-04). Pragmatism in the Age of Jihad: The Precolonial State of Bundu. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52847-4. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Richard (1975-09-18). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haggett, Peter (2002). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 978-0-7614-7306-0. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrison, Christopher (2003-09-18). France and Islam in West Africa, 1860-1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-521-54112-1. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam:. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Isichei, Elizabeth (1997-04-13). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-521-45599-2. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2002-08-22). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ndukwe, Pat I. (1996). Fulani. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8239-1982-6. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ogot, Bethwell Allan (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. UNESCO. p. 289. ISBN 978-92-3-101711-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ogot, Bethwell Allan (2010). História Geral da África – Vol. V – África do século XVI ao XVIII. UNESCO. p. 346. ISBN 978-85-7652-127-3. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rashedi, Khorram (January 2009). Histoire du Fouta-Djallon. Harmattan. p. 38. ISBN 978-2-296-21852-9. Retrieved 2013-02-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ruthven, Malise (2006-02-24). Islam in the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977039-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sanneh, Lamin O. (1997). The Crown and the Turban: Muslims and West African Pluralism. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-8133-3058-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J.; Carolyn M. Elliott (2012-01-05). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thornton, John (1998-04-28). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62724-5. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- U.N. Comité de culture (1999-01-01). Histoire générale de l'Afrique.: Volume V, L'Afrique du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-201711-6. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willis, John Ralph (1979). Studies in West African Islamic History. Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-1737-4. Retrieved 2013-02-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)