Kalandia

Kalandia (Arabic: قلنديا, Hebrew: קלנדיה), also Qalandiya, is a Palestinian village located in the West Bank, between Jerusalem and Ramallah, just west from the Jerusalem municipality boundary. In 2006, 1,154 people were living in the village according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.[2] Kalandia is also the name of a refugee camp, established by UNRWA in 1949. It is located just east from Jerusalem municipality. Kalandia refugee camp was built for Palestinians refugees from Lydda, Ramle and Jerusalem of the 1948 Palestinian exodus.[3]

Qalandia/Kalandia | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | قلنديا |

| • Latin | Qalandiya (unofficial) |

Kalandia refugee camp | |

Qalandia/Kalandia Location of Qalandia/Kalandia within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°51′47″N 35°12′27″E | |

| Palestine grid | 169/141 |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Jerusalem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,289 dunams (3.3 km2 or 1.3 sq mi) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 25,595 |

| • Density | 7,800/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Kulundia, personal name[1] |

History

Ancient tombs have been found at Kalandia.[4]

A Byzantine bath has been excavated, and pottery from the same period has also been located there.[5][6]

During the Crusader period, it was noted that Kalandia was one of 21 villages given by King Godfrey as a fief to the canons of the Holy Sepulchre.[4][7][8][9] In 1151 the Abbot leased the use of the vineyards and orchards of Kalandia to a Nemes the Syrian and his brother Anthony and their children. In return the convent was given a part of the yearly production from these fields.[10] In 1152 Queen Melisende exchanged villagers whom she owned for shops and two moneychanger counters in Jerusalem. All the names of the Kalandia villagers were Christian, which indicate that Kalandia was a Christian village at the time.[11][12]

Ottoman era

Kalandia, like the rest of Palestine, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, and in the Ottoman census of 1596, the village, called Qalandiya, was a part of the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Al-Quds which was under the administration of the liwa ("district") of Al-Quds. The village had a population of 15 households, all Muslim, and paid a fixed tax rate of 33.3% on wheat, barley, olives, beehives and/or goats, in addition to occasional revenues; a total of 3,900 akçe.[13]

In 1838, it was noted as a Muslim village in the Jerusalem District.[14][15]

In 1863, the French explorer Victor Guérin visited the village, which he described as small hamlet consisting of a few houses with fig plantations around them,[16] while an Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed 16 houses and a population of 50, though the population count included only the men.[17][18]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described the village as a "small village on a swell, surrounded by olives, with quarries to the west."[19]

In 1896 the population of Kalandije was estimated to be about 150 persons.[20]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Qalandieh (Qalandia) had a population of 144, of which 122 Muslims and 22 Jews.[21] This had decreased in the 1931 census when Qalandiya had an all-Muslim population of 120, in 25 houses.[22]

In the 1945 survey, Kalandia had a population of 190 Muslims,[23] and a land area of 3,940 dunams.[24] 427 dunams were designated for plantations and irrigable land, 2,202 for cereals,[25] while six dunams were built-up.[26]

Kalandia airport

Until 1927, Kalandia was the only airport in Mandatory Palestine, although there were several military airfields. Kalandia was used for prominent guests bound for Jerusalem.[27] It opened for regular flights in 1936.[28] After the Six-Day War, it was renamed Atarot Airport by Israel, but closed down due to disturbances related to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and because international companies refused to land there.[29] Israel confiscated 639 dunums from Kalandia village in order to establish a military base at the former airport.[30]

1947–1949

During the 1947–1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine, in early January 1948, the residents of Kalandia evacuated the village and moved to Ramallah, leaving a few young men to protect the property and make sure mines were not planted on the way leading to the village and the nearby mine.[31] The villagers returned to the village and after the news of the Deir Yassin massacre arrived the women, the children and most of the men were evacuated again and the village became a post of the Arab Liberation Army[32] In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Kalandia came under Jordanian rule. It was annexed by Jordan in 1950.

Kalandia refugee camp

The Qalandia refugee camp was established in 1949 by the Red Cross[34] on land leased from Jordan. It covers 353 dunums (0.353 km2; 35.3 ha) as of 2006[35] and has a population of 10,024[36] with 935 structures divided into 8 blocks.[35] Israeli authorities consider it part of Greater Jerusalem, and it remains under their control.[37]

1967-present

Since the Six-Day War in 1967, Kalandia has been under Israeli occupation.

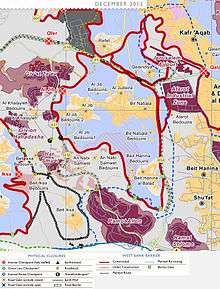

After the 1995 accords, 2% of Qalandiya’s land was classified as Area B, while the remaining 98% is Area C.[30] Israel has confiscated 574 dunams of land from Qalandiya in order to construct the Israeli industrial settlement Atarot and 639 dunams for the Israeli Qalandiya military base.[30] 1,940 dunums of the village, 59.3% of the village’s total area is isolated behind the Israeli West Bank barrier.[38]

Kalandia checkpoint

Kalandia is the main checkpoint between the northern West Bank and Jerusalem. The checkpoint is used by the Israeli military to control Palestinian access to East Jerusalem and Israel. Israel requires Palestinians to have permits to pass through the checkpoint to East Jerusalem and Israel for their work, medical care, education or for religious reasons.[39][40][41] According to B'Tselem, most of the people who use the checkpoint are residents of East Jerusalem separated from the city by the Israeli West Bank barrier.[42]

The Israeli 2013 Qalandia raid led to clashes with local residents, leaving three of Qalandia's inhabitants dead and several critically wounded.[43]

References

- Palmer, 1881, p. 321

- Projected Mid -Year Population for Jerusalem Governorate by Locality 2004- 2006 Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Kalandia Refugee Camp

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 11

- Dauphin, 1998, p. 844

- Baramki, 1933, pp. 105-109

- de Roziére, 1849, p. 30: Calandria, p.263: Kalendrie, cited in Röhricht, 1893, RRH, pp. 16-17, No 74

- Röhricht, 1904, RHH Ad, p. 5, No. 74

- Rey, 1883, p. 387

- de Roziére, 1849, pp. 159-160, cited in Röhricht, 1893, RRH, p. 67-68, No. 267

- Röhricht, 1893, RHH, pp. 70-71, No 278

- Ellenblum, 2003, pp. 235 -236

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 116

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol.3, Appendix 2, p. 122

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 2, pp. 137, 141, 315

- Guérin, 1868, p. 393, Guérin, 1869, p. 6

- Socin, 1879, p. 155

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 127, also noted 16 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, pp. 10-11

- Schick, 1896, p. 121

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Jerusalem, p. 15

- Mills, 1932, p. 42

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 25

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 58

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 103

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 153

- An Empire in the Holy Land: Historical Geography of the British Administration of Palestine, 1917-1929 Gideon Biger, St. Martin's Press and Magnes Press, New York & Jerusalem, 1994, p. 152

- Atarot and the Fate of the Jerusalem Airport

- Larry Derfner (January 23, 2001). "An Intifada Casualty Named Atarot". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- Qalandiya Village Profile, p. 16, ARIJ

- Gelber, 2004, p.139

- Gelber, 2004, p.162

- Garcia-Navarro, Lourdes (2012-07-26). Latest Target For Palestinians' Protest? Their Leader. NPR, 26 July 2012. Retrieved from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-207480084.html Archived 2014-06-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gelber, 2004, p.363

- Kalandia Refugee Camp Profile Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Kalandia Refugee Camp

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (date unknown). Where We Work - West Bank - Camp Profiles - Kalandia. "The Israeli authorities consider this area as part of Greater Jerusalem, and the camp was thus excluded from the redeployment phase in 1995. Kalandia camp remains under Israeli control today." Retrieved from http://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/west-bank/camp-profiles?field=12&qt-view__camps__camp_profiles_block=3.

- Qalandiya Village Profile, p. 17, ARIJ

- OCHA Commercial Crossings Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine report of 22 January 2008

- Hubbard, Ben, (Associated Press), "Checkpoint misery epitomizes a Mideast divide", NBC News, February 21, 2010.

- Barahona, Ana (2013). Bearing Witness - Eight weeks in Palestine. London: Metete. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-908099-02-0.

- "Qalandiya Checkpoint, March 2014: An obstacle to normal life". B'Tselem. March 2014.

- Funerals held for three Palestinians shot dead by Israeli troops, The Guardian, Monday 26 August 2013

Bibliography

- Baramki, D.C. (1933). "A Byzantine Bath at Qalandia". Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities in Palestine. 2: 105–109.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Ellenblum, Ronnie (2003). Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521521871.

- Gelber, Y. (2004). Independence Versus Nakba. Kinneret Zmora-Bitan Dvir. ISBN 965-517-190-6.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rey, E.G. (1883). Les colonies franques de Syrie aux XIIme et XIIIme siècles (in French). Paris: A. Picard.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Röhricht, R. (1904). (RRH Ad) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani Additamentum (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- de Roziére, ed. (1849). Cartulaire de l'église du Saint Sépulchre de Jérusalem: publié d'après les manuscrits du Vatican (in Latin and French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

External links

- Welcome To Qalandiya

- Qalandia, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Qalandiya Village (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem, (ARIJ)

- Qalandiya Village Profile, ARIJ

- Qalandiya areal photo, ARIJ

- Locality Development Priorities and Needs in Qalandiya, ARIJ

- Kalandia Refugee Camp, articles from UNRWA.

- Photostory: The Kalandia Terminal

- Two Israeli families attacked in Qalandiya after losing their way

- Kalandia Checkpoint acts as door to Jerusalem