KV20

KV20 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt). It was probably the first royal tomb to be constructed in the valley. KV20 was the original burial place of Thutmose I (who was later re-interred in KV38) and later was adapted by his daughter Hatshepsut to accommodate both her and her father. The tomb was known to the Napoleonic expedition in 1799, but a full clearance of the tomb only was undertaken by Howard Carter in 1903, although it had been visited by several explorers between 1799 and 1903. KV20 is distinguished from other tombs in the valley, both in its general layout and because of the atypical clockwise curvature of its corridors.

| KV20 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burial site of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut | |||

KV20 | |||

| Coordinates | 25°44′20.7″N 32°36′12.4″E | ||

| Location | East Valley of the Kings | ||

| Discovered | before 1799 | ||

| Excavated by | James Burton (1824) Howard Carter (1903-1904) | ||

Exploration and excavation

The location of KV20 was known to the French expedition of 1799 and to Belzoni, who worked in the area in 1817.[1][2] A first attempt to excavate the tomb was undertaken by James Burton in 1824, who cleared it as far as the tomb's first chamber.[1] Although Lepsius explored it in 1844 and 1845,[2] no further attempts to excavate the tomb were undertaken until Carter started his clearance of the rock-hard fill in the corridor in the spring of 1903.[1] This excavation was conducted by Carter as Inspector of the Antiquities Service, but the work was sponsored by Theodore M. Davis, who published a report of the work in 1906.[3]

After Carter's work in the tomb ended, no further activities have been carried out. Since 1994 the burial chamber has been inaccessible due to debris deposited by flooding.[2]

Location, layout, and contents

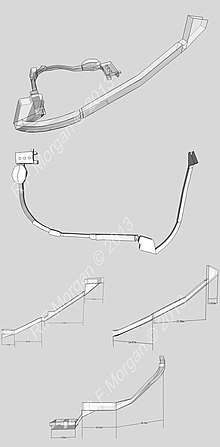

KV20 is located in the easternmost branch of the valley near the later tombs KV19, KV43, and KV60. Its plan is of unusual shape, consisting of a series of five curving, descending corridors, two of which end in chambers. These corridors bend east-south-west in a clockwise fashion, which is a unique feature amongst the tombs in the valley. At the bottom of this descending passage is a suite of chambers, connected to each other by a further corridor. The burial chamber is a three-pillared room and it has three small side-rooms at its northern end. The tomb has a total length of 210 meters.[2]

The upper part of the corridors is cut into good quality limestone, but the lower parts of the passage and the chambers at the bottom are cut in a layer of softer shale. Because of this difference, the lower parts of the tomb, including the roof of the burial chamber, have collapsed partially.[2] The soft rock in the burial chamber also was unsuitable for decoration and therefore, limestone slabs inscribed with chapters from the Amduat in red and black inks were intended to line the walls.[4] Carter found fifteen of these slabs in the burial chamber [4] while other similar blocks, probably from the same series, were found in KV38.[5]

Apart from a foundation deposit of Hatshepsut, the only objects found in KV20 come from the burial chamber and the corridor leading into it. Items found were stone vases bearing the names of Ahmose-Nefertari, Thutmosis I, and Hatshepsut, two quartzite sarcophagi inscribed for Thutmose I and Hatshepsut (as pharaoh), a canopic chest for Hatshepsut (again as pharaoh), the limestone blocks bearing funerary text (see above), and several fragments of the usual funerary furnishings.[4] The sarcophagus of Thutmose originally was inscribed for Hatshepsut, but later altered for the former king.[6]

Other items associated with KV20

A box inscribed for Hatshepsut as pharaoh, containing the remains of a mummified liver or spleen was recovered from the DB320 royal cache.[7] Other items associated with Hatshepsut, including the legs and footboard of a couch or bed and a fragmentary cartouche-shaped lid are of uncertain origin, but might come from either the Deir el Bahari cache or KV6 (tomb of Ramesses IX).[7]

Fragments of at least one anthropoid coffin belonging to a mid-eighteenth dynasty female ruler (presumably Hatshepsut), fragmentary wooden panels with decoration that links them to objects found in KV20, and a faience vessel, possibly belonging to Thutmose I, were recovered from the shaft in the burial chamber of KV4, together with remains of royal funerary equipment belonging to several other New Kingdom rulers.[8]

History

Despite the foundation deposit of Hatshepsut and the existence of another tomb for Thutmose I, (KV38), it is now generally presumed that KV 20 originally was quarried for the latter king.[2] Re-evaluation of the architecture of KV38 and some of its content has shown that it is unlikely that this tomb pre-dates the reign of Thutmose III.[9] It also has been noted that the proportions of the KV20 burial chamber are different from those in the rest of the tomb and that they display a design relationship to the architecture of Hatshepsut's pharaonic mortuary temple.[10]

It therefore has been suggested that KV20 extended originally, only to its present penultimate chamber in which Thutmose I first was interred, and that the tomb was re-cut and refurbished during the reign of Hatshepsut to accommodate the burial of both her and her father.[11] Later the burial of Thutmose I was moved again, into KV38, by his grandson Thutmose III while the burial of Hatshepsut probably remained in KV20, eventually suffering from robbery (and official dismantling).[11]

An unidentified mummy, recovered from DB320 and found within coffins prepared by Thutmose III for Thutmose I is usually identified as the later king.[12] The body of Hatshepsut has not yet been identified with certainty and the mummified liver or spleen found in DB320 might be all that remains of her,[13] although it also has been suggested that one of two female mummies found in KV60 is her.[2][14] A molar found in the wooden box containing her liver, was matched to one of these mummies in 2007, making it likely that the mummy belongs to Hatshepsut.[15][16]

References

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 13

- "KV 20 (Thutmes I and Hatshepsut) - Theban Mapping Project". www.thebanmappingproject.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 296-297

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings, (kegan Paul, 1990) p.13

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings, (kegan Paul, 1990) p.28

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings, (kegan Paul, 1990) p.27

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings, (kegan Paul, 1990) p.17

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings, (kegan Paul, 1990) pp.121-122

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 13 and 17-18

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 13-17

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 17

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 244

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 245

- http://www.guardians.net/hawass/hatshepsut/search_for_hatshepsut.htm

- Wilford, John Noble (June 27, 2007). "Tooth May Have Solved Mummy Mystery". New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

A single tooth and some DNA clues appear to have solved the mystery of the lost mummy of Hatshepsut, one of the great queens of ancient Egypt, who reigned in the 15th century B.C.

- "Tooth Clinches Identification of Egyptian Queen". Reuters. June 27, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

External links

- Theban Mapping Project: KV20 - Includes description, images, and plan of the tomb