KV4

KV4 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt). The tomb was initiated for the burial of Ramesses XI but it is likely that its construction was abandoned and that it was never used for Ramesses's interment. It also seems likely that Pinedjem I intended to usurp this tomb for his own burial, but that he too abandoned the plan. KV4 is notable for being the last royal tomb that was quarried in the Valley and because it has been interpreted as being a workshop used during the official dismantling of the royal necropolis in the early Third Intermediate Period.

| KV4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burial site of Ramesses XI | |||

KV4 | |||

| Coordinates | 25°44′26.5″N 32°36′10.3″E | ||

| Location | East Valley of the Kings | ||

| Discovered | Open since antiquity | ||

| Excavated by | John Romer (1978-1980) | ||

Exploration and excavation

Although KV4 has been open since antiquity and graffiti from various ages attest to its popularity as an early tourist attraction[1] it received little scholarly attention until John Romer's clearance in 1978-1980.

Location, layout and contents

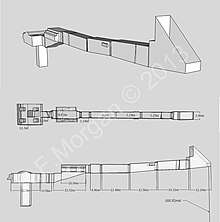

KV4 is located in one of the valley's side wadis, next to KV46. Running back over 100 metres into the mountainside, it consists of a series of three gently sloping corridors leading towards the tomb's well chamber (although no shaft is cut in its floor) and two unfinished, pillared chambers.[1] The latter of these chambers, the burial chamber, features a deep shaft cut into the centre of its floor;[1] foundation deposits of Ramesses XI associated with it might indicate that its cutting was contemporary with the original plan of the tomb.[2]

Decoration was only present on the lintel and jambs of the outer doorway and in the first corridor which has preliminary sketches in red ink on the plastered walls. Part of the decoration in the corridor was already damaged in antiquity and was later restored by Pinedjem I who replaced the king's names with his own in these restored scenes.[1]

Romer's excavation of KV4 brought to light five groups of objects.

- Items originating from KV62 (tomb of Tutankhamun): fragmentary items discovered amongst the rubble fill in the corridor of KV62 and sections of the blockings from the inner and outer doorways of that corridor. These include the Head of Nefertem. The presence of these items in KV4 date from the time of Howard Carter's clearance of KV62.[3]

- Evidence of Coptic activities in the tomb: the remains (in the corridors and well chamber) of a beaten mud floor and a rough stone wall, together with shards of decorated pottery and a Byzantine copper mint.[2]

- Remains of an intrusive 22nd Dynasty burial: found in the shaft of the burial chamber and consisting of bones, fragments of cartonnage and a partial coffin. This material showed signs of burning and it is likely that this burial was desecrated during the time of the Coptic presence in the tomb.[2]

- Fragmentary remains of several New Kingdom royal burials: found in the burial chamber and in the lower levels of the shaft which seems to have been undisturbed since the late New Kingdom. These include fragments of gilded gesso (some coming from a royal coffin), fragments of wooden panels that are linked stylistically with objects found in KV20 (tomb of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut) and KV35 (tomb of Amenhotep II), fragments of at least one anthropoid coffin from a mid-18th Dynasty female ruler (probably Hatshepsut), a faience vessel bearing the Horus name shared by Thutmose I and Ramesses II, wooden statue bases (some bearing the prenomen of Thutmose III), fragments of a foot which matches with a wooden goose found in KV34 (tomb of Thutmose III) and shabtis belonging to Ramesses IV.[4]

- Foundation deposits of Ramesses XI: these were associated with the shaft in the burial chamber (see above)[2]

History

That KV4 was originally quarried for the burial of Ramesses XI is evident from the decoration in the corridor and the foundation deposits associated with the shaft. It appears however that this plan was abandoned in favour of a burial elsewhere (perhaps in Lower Egypt)[5] The most likely explanation for Pinudjem's later restoration and the insertion of his cartouche would be that he intended to usurp the tomb at the beginning of his kingship, but this plan too was abandoned for an interment elsewhere, perhaps in the tomb of Inhapi[6] (tomb WNA or possibly DB320[7]) a tomb that was subsequently also used to rebury royal mummies from the Seventeenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom. These abandoned burial plans are perhaps to be associated with the apparent general abandonment of the valley as a royal necropolis and the start of the restoration and reburial of earlier pharaohs during the Wehem Mesut period.[8]

After Pinudjem's abandoned usurpation of KV4 it appears the tomb was used as a workshop to process funerary equipment from other royal tombs, most notably the burials of Thutmose I, Thutmose III and Hatshepsut. In this context a link is made between the gilded gesso fragments found in KV4 and the coffin of Thutmose III that was found in the DB320 cache. This coffin had been carefully stripped of the major portions of its gilded surface in antiquity and it has been suggested that this stripping was done in KV4. The fact that the individuals involved in these activities went through the time consuming procedure of scraping of the coffin's surface without impairing its basic function as a container for the king's mummy, suggests this was not the work of common tomb robbers. The material recovered from KV4 has therefore been interpreted as evidence for a changed official policy towards the burials in the valley in which they were stripped of valuable commodities in an attempt to safeguard them from tomb robbers by making them less attractive, while at the same time the recovered valuables were used to refill the depleted treasuries of the period.[8]

During the Byzantine period the open tomb was used by Copts as a residence and stable, while during the clearance of KV62 by Howard Carter in the 1920s it was used as a dining area and a storeroom, the latter during the early stages of that clearance before KV15 was made available for that purpose.[9]

References

- "KV 4 (Rameses XI) - Theban Mapping Project". www.thebanmappingproject.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-10. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 121

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 81 and p. 126

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 121-122

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) p.122

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 123 and p.127

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 187-192

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) p. 123

- Reeves, C.N., Valley of the Kings: Decline of a Royal Necropolis (Kegan Paul, 1990) pp. 122-123

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to KV4. |

External links

- Theban Mapping Project: KV4 - Includes description, images and plans of the tomb.