Josef Hammar

Josef Hammar (born November 15, 1868 in Helsingborg – died August 4, 1927 in Bouzaréa) was a Swedish military surgeon and adventurer. Hammar was a renowned doctor who saw active service in the second Boer War and the siege of Ladysmith. He also served as a military attaché in the Russo-Japanese War and the siege of Port Arthur.

Doctor Josef Hammar | |

|---|---|

Hammar taken in Hiroshima December 1904 | |

| Born | November 15, 1868 Helsingborg |

| Died | August 8, 1927 (aged 58) Bouzaréa |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Education | Lund University, Karolinska institutet |

| Occupation | Military surgeon, Adventurer |

| Years active | 1898–1926 |

| Known for | Renowned doctor |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Military surgeon |

| Awards | Japanese campaign (Russio-Japanese war) and merit medals, Knight of the Spanish White Cross of Military Merit, 1st class, Member of The Royal Military Science Academy |

Biography

Early life

Josef Hammar was son of August Hammar, a vicar in Nosaby, Sweden, and his wife Elin Jakobina Juliana Ask. After his matriculation in Helsingborg May 31, 1886,.[1] he joined the university in Lund. On September 14, 1888, he took a Medico-Philosophical degree[1] and in 1889 he registered at the Karolinska Institute to study medicine. Four years later on February 15, 1893, he achieved his Candidate of Medicine.[1][2]

He continued his studies and practice and between March and May, 1894 he attended courses in Berlin and Dresden[1] and visited Karlsbad. On June 21, 1895 he is returned to Lund as an assistant at the obstetrical clinic where he practised until April, 1896.[1] In the summer of 1896, he became a medical field scholar of the 2nd degree[2] and served with The Royal South Skånska Infantry Regiment. The year after, he practiced at The Skånska Cavalry Regiment, followed by The Royal Lifeguards Hussars and The Royal Vedes Artillery Regiment. On September 15, 1898, he took his degree as Licentiate of Medical Science in Lund, becoming a certified doctor.[1][2] His first job was as a temporary district doctor in Hammenshög district.[1]

In search of Salomon August Andrée

After having spent a month in the northern part of Sweden as a temporary doctor at the state rail-road between Boden and Morjärv in the spring of 1899[1] Hammar joined A. G. Nathorst's expedition towards Greenland as the expeditions doctor. Nathorst had performed a similar expedition the year before and considered that to be his last expedition, but heeding the call "Proposal for an expedition to eastern Greenland in search of Andrée and his companions" [3] he decided to make a second expedition. Two years earlier Salomon August Andrée had staged an air balloon expedition to the North Pole. Hammar had, together with a friend, applied to join the Andrée expedition but was not accepted.[4]

The expedition sailed with the ship Antarctic from Stockholm at 10 am on May 20, 1899. Travelling around Sweden's southern end and out on the North Sea. On June 22 they reach Jan Mayen, an Island east of Greenland and towards the east coast of Greenland in the beginning of July. They start to map the coast southwards making frequent shore raids collecting minerals and hunting animals. Hammar's main mission was to excavate traces of Eskimo villages and collect ethnographic remains. Some 278 items found are still in the collections of the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm[5] There is an extensive account of this expedition in A.G. Nathorst's books Två somrar i Ishavet (Two summers in the Arctic Ocean).[3]

The expedition arrives back to Stockholm on September 17, 1899.

Canoeing pioneer

Hammar was an early Swedish canoeist and kayaker. He brought along the canoe Kajaka for the 1899 Greenland expedition. Kayaka was constructed by the Swedish naval officer Carl Smith. [6] Later, Josef Hammar became member of Sweden's oldest canoe club, Föreningen för Kanot-Idrott.

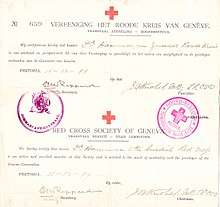

Second Boer War

In the autumn of 1899 the Second Boer War started. After some lobbying Hammar received grants from the Swedish government and the Swedish Red Cross to travel to South Africa as a doctor.[7] Through contacts in Stockholm he got Sweden's foreign minister Alfred Lagerheim together with the Swedish envoy in Brussels, August Gyldenstolpe, to send the following telegram to the South African Republics Consul General in Amsterdam:

"Dr. Hammar, 30 years old, military physician and surgeon, with the best recommendations from the Swedish Medical Board and the official representative of The Red Cross, wishes to ask whether he may put himself to the Transvaal Republics disposal. He departs from Hamburg on the 25th and arrives in Amsterdam on the 28th. Please reply through telegram whether You want to give him a letter of recommendation and work (employment) with the Republic. - Signed Count Gyldenstolpe"[8]

After some communication he decided to associate himself to a Dutch ambulance as he couldn't raise enough money for an ambulance from Sweden. Travelling through Holland via Italy and the Suez channel he arrived to South Africa and Pretoria in the beginning of December 1899. There he visited President Paul Krüger who expressed his gratitude to the Swedish government and the Swedish Red Cross for sending them a doctor.[9] It was decided that he was more needed in one of the governments ambulances than in the Dutch ambulance as they had a shortage of doctors.

After a week in Pretoria, Hammar set off to the front at the siege of Ladysmith where he helped the Dutch ambulance to set up a major field hospital. During this he received an offer to take the doctors position at one of the Boer commandos - The Utrecht Commando. This 500 men strong commando was positioned between Ladysmith and the front at Colenzo. The ambulance was staffed with six white and eight black men and featured two ox carts together with 24 oxen, 8 mules and 7 riding horses.[9] As the fighting escalated the casualties raised. On January 6, 1900, the Boers performed an assault on a British fortification Matrand by Ladysmith where Hammar came under direct artillery fire while dressing a wounded Boer. A second battle at Tugela on January 20 to 25 was 25 miles from their position, to far to take the ox carts but Hammar rode there. Although the casualties was much more his allotment was only three wounded.[9] This was the first British push to liberate Ladysmith. Hammar then participated as a field surgeon in three battles, the storming of Ladysmith where his commando suffered big losses, then one at Spioenkopf and finally the eleven days long battle by Colenzo and Pieterstasie where the British finally managed to relieve Ladysmith.

After the siege of Ladysmith was broken, Hammar's commando moved up to the Biggars mountains under constant shelling. Hammar escaped unharmed but somewhat starving as the only things they had to eat was some old biscuits. This did not concern him so much as he was suffering from dysentery and could not eat anything anyway.[10] After a short quite time they had to pull back again and by this time his commando had shrunk to about 30 men so Hammar requested leave from the commandant and left for Utrecht and then back to Pretoria. There he was offered another ambulance stationed by Amajuba. When he arrived there however the railroad to Pretoria was cut off and the British seized Johannesburg and advanced on their position and the Boers fled. As he never received his ambulance Hammar decided to start his journey home.

Dressed in a single set of thin clothes he rode over the entire Transvaal, over Ermelo and Carolina to the railroad in Machadodorp where he arrived on June 20 after ten days in the open. At Machadodorp president Krüger had placed his temporary capital, i.e. his railway carriage where he lived. Before leaving, which he did the same day, Hammar visited president Krüger a last time. From Machadodorp Hammar managed to take a train to Delagoa Bay where he arrived in the clothes he was carrying and no money. All his belongings was left in Pretoria. He was saved by some Norwegians he met who gave him money. On June 25, 1900, he arrived to Pietermaritzburg to the home of his brother August and his family who was living all this time on the British side of the conflict.

Hammar went to South Africa with a sympathetic view on the Boers and the Boer cause. During the conflict his views changed as he experienced the undisciplined state of their forces, their poorly organized supplies and their general mindset. In his accounts he is very critical against all this but as he states in a lecture note: "If some of my statements about the Boers, which has not been flattering, should give you the idea that I, through my personal acquaintance with the Boers, have lost my esteem for them then this is not correct. The sympathy for the Boers and their cause, that at the start of the war made me travel down to their help, I still carry to a non lessened degree."[11]

Years in between

Arriving back from South Africa Hammar made several lectures about his experiences. He received a medical field scholar of the 1st degree September 25, 1899.[2][7] Between April and August, 1901 he is temporary assistant physician at the general garrison hospital in Stockholm.[1][7] Between August 12, 1901, and May 19, 1904, he had a posting as battalion doctor at The Royal Jämtlands Rifle Regiment in northern Sweden.[1][2][7] Under that time he also practiced as doctor in Literature in 1902 and in Nynäshamn in 1903.[7]

In March 1903 he received a military physician grant for a trip to Holland to study medical equipment.[1][7] After attending a military physician training in the autumn he got a posting as battalion doctor at The Royal Position Artillery Regiment.[2]

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War started in February 1904 and Hammar was ordered to travel to the war as a military attaché to study how the military healthcare was handled by the Japanese.[7] He got a grant of 5,000 kronor (approx. $35,000 today) from his Majesty the King Oscar II to travel as a military attaché to the war for six months. However he thought this was to short and managed to get another 1,500 kronor (approx. $10,500 today) for another two months. In addition to this he made deals with Stockholms Dagblad, Göteborgs Handels- och Sjöfartstidning and Aftenposten to send reports from the war, each deal worth a maximum of 500 kronor (approx. $3,500 today).[12]

Hammar traveled to London where he stayed at Hotel Victoria for a few days. Then he boarded the Schenellendampfers "Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse" on June 8, 1904, to cross the Atlantic with a seat at Herr Capt. O. Cüppers table. He arrives in Hoboken, New Jersey and stayed at Hotel Naegeli on June 14, then onward by Pullman train to Chicago. Here he changed for Overland Limited and Union Pacific to San Francisco where he arrives on June 18, just 10 days after he left London. He is in S.F. for a couple of days staying at The Palace Hotel. While staying here he was approached by a tramp who he immediately recognized as his cousin 'Conne' (Constans) Hammar. Conne had emigrated to America some 7 years earlier and not been heard of since. Now he was struggling as a gardener in S.F. On June 22, 1904, Hammar boarded the S.S. Coptic for Yokohama via Honolulu. He arrived to Yokohama on July 11, 1904, 19 days after setting out from San Francisco.

Hammar immediately went to Tokyo where he sorted out all formalities meeting with the Japanese war minister General Terauchi Masatake. He was then instructed to meet with General Major Koike, head field physician. He was handed a little green book which, he was explained, was very secret. The book contained a description of how the Japanese field medical care was organized and Hammar was instructed to read this before he was permitted to visit any military hospitals. On a question whether the English military surgeon Lieut. Col. MacPherson had read it, he was answered "No! No!".

Hammar visited military hospitals in Tokyo and studied various war wounds. He also showcased some equipment he brought from Sweden. On August 2 he travelled to Hiroshima and visited the two hospitals in town of which one was the largest military hospital in Japan led by General Doctor Sato. When Hammar visited the hospital housed some 2000 patients but it had capacity for 4000. Barracks was under construction to increase the number to 7000.

On August 5, 1904, Hammar boarded the hospital ship Hakuai-maru with destination Dalny where they arrive on August 9. From Dalny he travelled to the front at Port Arthur. At four in the morning on August 21 he climbed a mountain in order to witness the big attack on Port Arthur. The attacks had started on August 8 and by the 21 the Battle of 174 Meter Hill raged and the casualties where high. General Nogi called off the attack by August 24 and concentrated on a prolonged siege.[13]

Hammar stayed at the front by Port Arthur for four months visiting dressing stations, field hospitals and other medical departments of the Japanese army. He lived together with the other foreign officers. They were ten, four Englishmen, one Turk, one Chilean, one Spaniard, one Brazilian, one German and himself. To start with they lived in tents but were later moved to a house. On one occasion the Spaniard, Captain Herrera, was wounded and Hammar walked into the bullet rain with his horse and lifted the Captain up on the horse and walked back to safety.[4] For this he was later awarded the knighthood of the Spanish White Cross of Military Merit, 1st class.[14]

The siege continued until January 5, 1905, but Hammar had no time to stay and left for Japan on December 11. First he went back to Hiroshima for two weeks. There they now nursed some 10,000 wounded. After that he travelled back to Tokyo where there was some 15,000 wounded. In total at that time there was some 50,000 wounded in different places around Japan. Hammar was admitted before the Emperor Meiji who asked him questions and shook his hand twice. The day before the visit, Hammar was sent the Order of the Sacred Treasure fourth class.[13][14] Later he also had an audience with the Empress.

Hammar left Yokohama with the French S.S. le Polynésien on February 11. The boat rested at many harbours on the way where the passengers had time to walk the town. First stop was Shanghai followed by Hong Kong, Saigon, Singapore, Ceylon, Aden, Port Said and finishing in Marseille. After Marseille, Hammar went to Berlin for a period before travelling home to Stockholm in April 1905.

Family

On his way home from Japan, Hammar stopped in Marseille to visit friends of the family, the family of Wholesaler Adolf Sylvander. There he met Adolf's daughter Hulda Sylvander (born September 18, 1881, in Marseille - died April 3, 1971) and they subsequently married a year later August 8, 1906, in Marseille. Josef and Hulda had four children:

- Frank Hammar (born January 3, 1908 in Marseille - died October 27, 1974 in Motala), Master of Science at Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan. Managed Haile Selassie's radio station in Addis Ababa, in the mid 1930s.[15] Later Managing Director of Standard radio & telefon AB[16]

- Mireille Hammar (born April 21, 1909, in Stockholm - died July 29, 1959, in Stockholm), married the Swedish actor Olof Widgren

- Gösta Hammar (born May 29, 1911 in Stocksund - died November 6, 1978 in Västerås), coffee plantation owner in Dumbi-Cassongue, Angola

- Ulla Hammar (born November 4, 1912 in Stocksund - died April 9, 1987 in Marseille), married her cousin George Sylvander and moved to Marseille

Back in Sweden

When Hammar arrived back to Sweden he performed lectures and wrote the article "About the medical service in the Japanese third army"[17] about his experiences from the Russio-Japanese war. Because he had unique experiences from warfare (not common in Sweden at that time) he was assigned as extra assistant at the Swedish Army Administration's healthcare agency 1905 - 1907.[7] On commission from the Municipal av Stockholm he carries out studies on health in public schools 1906-1907.[7] Hammar published at least two studies on why schoolchildren were so tired during lessons. He received Captain's rank on September 15, 1907.[2][7] During the summer that year, 1907, he traveled to London as Sweden's representative at the international conference on school hygiene.[7] In 1908 he was chosen as a member of the committee to reorganize the Swedish Field Doctor Corps.[7][18]

In 1908 he also traveled to Skodsborgs Spa to study metabolic and heart diseases.[7] In 1910 he was elected as a member of the Royal Academy of Military Science.[19] During the winter 1910-1911 Hammar studied metabolic disorders under Friedrich von Müller in München again to study metabolic and heart diseases.[7] He also practised this with Dr. Landergren at Ramlösa. In spring 1912 he gets a government grant to study food distribution at the Austrian army for von Noorden in Vienna.[7]

Between December 1, 1915 and January 28, 1916, he travelled with his entire family through Germany and Switzerland to Marseille to visit the Huldas family. This was in the middle of World War I and there are traces that he also sought to visit the fighting to study the war medicine but there is no proof that this ever happened (also the short time frame talks against this).

On May 5, 1916, Hammar was assigned as Regiment Doctor in the Swedish Medicine Corps.[2][7] On December 14, 1917, he was posted as Regiment Doctor at the Skånska Dragonregimentet (Cavalry) in Ystad.[2][7] Between 1918 and 1920 he also acted as secondary City Physician in Ystad.[2][7]

Final adventure

Hammar tried to settle down in Ystad, bought a big house, cultivated fruit and vegetables, went biking and took long walks but to no avail. In 1923 he wrote to Lindskog:

"No man with my disposition can feel the wind under his wings without wishing himself out again. This is why my life under all these years, since I came under the military yoke, has been more like a frozen curse, an eternal regret over uncultivated forces."[4]

In 1926 it was decided to terminate the Skånska Dragonregimentet and Hammar was now free to pursue new goals. He bought a fruit farm in Bouzarea, Algeria. His first year was filled with hailstorms and his crops failed. He was still determined to continue but on August 8, 1927, he died from heart failure.[7]

Published articles[7]

- Från krigsskådeplatsen i Sydafrika (From The Theatre Of War In South Africa) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1900

- Rapport från kriget i Sydafrika I, II and III (Report From The War In South Africa pt. 1, 2 and 3) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1900

- Boernas sanitetståg (The Boer Hospital Trains) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1903

- Från kriget i Ostasien (The War In East Asia) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1904

- En kanottur i Kejsar Frans Josefs-fjorden (A canoe tour in the Kaiser Franz Joseph Fjord) - published in Kanotidrott. Utgifven av Föreningen för Kanot-Idrott vid dess 10-årsjubileum, Stockholm 1910

- Sjukvårdstjänsten vid 3:e Japanska armén (Health Care At The 3rd Japanese Army) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1910

- Japansk sjukvårdsmateriel (Japanese Medical Supplies) - published in Tidskriften i militär hälsovård, 1910

- Edited the sanitary section of Vårt fosterland och dess försvar (Our Motherland And It's Defence) 1906 - 1908

- Correspondent for Stockholms Dagblad and Göteborgs Hanels- och Sjöfartstidning during the Second Boer War

- Correspondent for Svenska Dagbladet during the Russo-Japanese War

Honours, decorations, awards and distinctions

- Field Doctor Scholarship 2nd class (April 1896)[2]

- Field Doctor Scholarship 1st class (September 1899)[2][7]

- Member of The Swedish Military Doctors Association (1899)[1][7]

- Member of The Swedish Medical Society (1899)[1][7]

- Military Doctor Scholarship (March - June 1903)[1]

- Knight of The Order of the Sacred Treasure 4th class (January, 1905)[7][13][14]

- Knight of The Royal Order of Vasa 1st class (May 15, 1905)[7][14]

- Japanese campaign and merit medals (Russio-Japanese war) (1906)[7]

- Knight of the Spanish White Cross of Military Merit, 1st class (December 1906)[7][14]

- Member of The Royal Military Science Academy (October 18, 1910)[7][19]

References

- Ljungfors, Vilhelm (103). Helsingborgs-Landskrona Nation i Lund - Biografiska anteckningar. Lund, Sweden: A. B. Skånska Centraltryckeriet. pp. 76–77.

- Svenskt biografiskt lexikon volume 18 (1969-1971), page 144 by Britt-Mari Bergvall

- Nathorst, A. G. (1900). Två somrar i Norra Ishafvet. Stockholm: Beijers bokförlagsaktiebolag. p. 1.

- From the leaflet Josef Hammar - commemorative words in The Swedish Military Doctors Society by Olof Hult published in Tidsktiften i militär hälsovård 1927.

- "1902.10 :: Hammar, Josef". Carlotta - The national database for museum collections. 1902-06-21. Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- Hammar, Josef: En kanottur i Kejsar Frans Josefs-fjorden, in Kanotidrott. Utgifven av Föreningen för Kanot-Idrott vid dess 10-årsjubileum, Stockholm 1910

- Widstrand, A (1932). Sveriges Läkarhistoria - Ifrån Kung Gustav Den I:s till närvarande tid. F–J. Stockholm: P. A. Nordstedt & söner Förlag. pp. 273–275.

- My South African year, 1899 - 1900, by Josef Hammar. An unfinished account stored in Hammar's family archive.

- Hammar, Josef (December 10, 1899). "From the theater of war in South Africa". I militär helsovård årg. 1900 (In Military Healthcare year 1900): 82.

- Josef Hammar's letter to his father, Biggars Mountains by Dundee, Natal, March 17, 1900.

- About the Boers and the war in South Africa. Preserved lecture notes for an unknown occasion in Hammar's family archive.

- Josef Hammar's diaries from his travels to Japan and back, 1904-1905.

- Hammar, Josef (April 15, 1905). "Fyra månader vid belägringshären". Östergötlands Veckoblad Östgöra-Posten.

- Sveriges Statskalender årgång 1907. (Swedish Bluebook year 1907)

- Norberg, Viveca Halldin (1977). Swedes in Haile Selassie's Ethiopia, 1924-1952. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies. pp. 142–144.

- "Standard Radio och Telefon AB" (PDF). Försvarets Historiska Telesamlingar. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- Published in Tidskrift i militär hälsovård - 1906, leaflet 4, p. 304

- Article "Fältläkarkårens omorganisation. - De sakkunnigas förslag." (The Reorganization of Swedish Field Doctor Corps - The experts proposition.) by Josef Hammar in "Allmänna Svenska läkartidningen" August 14, 1908.

- Hildebrand, Albin (1911). Svenskt porträttgalleri - XIII. Läkarekåren ny tillökad upplaga. Stockholm: Hasse W. Tullbergs förlag. p. 177.