John Shelby Spong

John Shelby "Jack" Spong (born June 16, 1931) is a retired bishop of the Episcopal Church. From 1979 to 2000, he was the Bishop of Newark, New Jersey. A liberal Christian theologian, religion commentator and author, he calls for a fundamental rethinking of Christian belief away from theism and traditional doctrines.[1]

The Right Reverend John Shelby Spong D.D., L.H.D. | |

|---|---|

| Bishop Emeritus of Newark | |

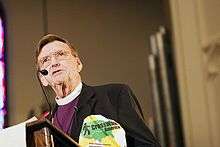

Spong in 2006 | |

| Church | Episcopal Church |

| Province | Province 2 |

| Diocese | Newark |

| In office | 1979–2000 |

| Predecessor | George Rath |

| Successor | John P. Croneberger |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | December 1955 by Edwin A. Penick |

| Consecration | June 12, 1976 by John Allin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 16, 1931 Charlotte, North Carolina |

| Nationality | American |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Parents | John Shelby Spong & Doolie Boyce Griffith |

| Spouse | Joan Lydia Ketner (m. 1952, d. 1988) Christine Mary Bridger (m. 1990) |

| Children | 5 |

| Previous post | Coadjutor Bishop of Newark (1976-1979) |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina Virginia Theological Seminary |

| Website | johnshelbyspong |

Early life and career

Spong was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, and educated in public schools there. He attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1952. He received his Master of Divinity degree from the Virginia Theological Seminary in 1955. He has had honorary Doctor of Divinity degrees conferred on him by Virginia Theological Seminary and Saint Paul's College, Virginia, as well as an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters conferred by Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania.

In 2005, he wrote: "[I have] immerse[d] myself in contemporary Biblical scholarship at such places as Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Yale Divinity School, Harvard Divinity School and the storied universities in Edinburgh, Oxford and Cambridge."[2]

Spong served as rector of St. Joseph's Church in Durham, North Carolina, from 1955 to 1957; rector of Calvary Parish, Tarboro, North Carolina, from 1957 to 1965; rector of St. John's Church in Lynchburg, Virginia, from 1965 to 1969; and rector of St. Paul's Church in Richmond, Virginia, from 1969 to 1976. He has held visiting positions and given lectures at major American theological institutions, most prominently at Harvard Divinity School. He retired in 2000. As a retired bishop, he is a member of the Episcopal Church's House of Bishops.[3] During his tenure as Bishop of Newark, confirmed communicants in the diocese fell by nearly 50%, from 44,423 in 1978, to 23,073 in 1996.

Spong describes his own life as a journey from the literalism and conservative theology of his childhood to an expansive view of Christianity. In a 2013 interview, Spong credits the late Anglican bishop John Robinson as his mentor in this journey and says that reading Robinson's controversial writings in the 1960s led to a friendship and mentoring relationship with him over many years.[4] Spong also honors Robinson as a mentor in the opening pages of his 2002 book A New Christianity for a New World.

Recipient of many awards, including 1999 Humanist of the Year,[5] Spong is a contributor to the Living the Questions DVD program and has been a guest on numerous national television broadcasts (including The Today Show, Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher, Dateline, 60 Minutes, and Larry King Live). Spong's calendar has him lecturing around the world.[6]

Spong is the cousin of former Virginia Democratic Senator William B. Spong, Jr.

By his own account, he is closely associated with the Unity Church.[7]

According to The Episcopal Diocese of Newark, Bishop Spong suffered a stroke before a speaking engagement in Marquette, Michigan on Saturday, Sept 10, 2016.[8]

Writings

Spong's writings rely on Biblical and non-Biblical sources and are influenced by modern critical analysis of these sources (see especially Spong, 1991). He is representative of a stream of thought with roots in the medieval universalism of Peter Abelard and the existentialism of Paul Tillich, whom he has called his favorite theologian.[9]

A prominent theme in Spong's writing is that the popular and literal interpretations of Christian scripture are not sustainable and do not speak honestly to the situation of modern Christian communities. He believes in a more nuanced approach to scripture, informed by scholarship and compassion, which can be consistent with both Christian tradition and contemporary understandings of the universe. He believes that theism has lost credibility as a valid conception of God's nature. He states that he is a Christian because he believes that Jesus Christ fully expressed the presence of a God of compassion and selfless love and that this is the meaning of the early Christian proclamation, "Jesus is Lord" (Spong, 1994 and Spong, 1991). Elaborating on this last idea he affirms that Jesus was adopted by God as his son (Born of a Woman 1992), and he says that this would be the way God was fully incarnated in Jesus Christ.[1] He rejects the historical truth claims of some Christian doctrines, such as the Virgin Birth (Spong, 1992) and the bodily resurrection of Jesus (Spong, 1994). In 2000, Spong was a critic of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of the Roman Catholic Church's declaration Dominus Iesus, because it reaffirmed the Catholic doctrine that the Roman Catholic Church is the one true Church and that Jesus Christ is the one and only savior for humanity.[10]

Spong has also been a strong proponent of the church reflecting the changes in society at large.[11] Towards these ends, he calls for a new Reformation, in which many of Christianity's basic doctrines should be reformulated.[1]

His views on the future of Christianity are, "...that we have to start where we are. As I look at the history of religion, I observe that new religious insights always and only emerge out of the old traditions as they begin to die. It is not by pitching the old insights out but by journeying deeply through them into new visions that we are able to change religion’s direction. The creeds were 3rd and 4th century love songs that people composed to sing to their understanding of God. We do not have to literalize their words to perceive their meaning or their intention to join in the singing of their creedal song. I think religion in general and Christianity in particular must always be evolving. Forcing the evolution is the dialog between yesterday’s words and today’s knowledge. The sin of Christianity is that any of us ever claimed that we had somehow captured eternal truth in the forms we had created."[12]

Spong has debated Christian philosopher and apologist William Lane Craig on the resurrection of Jesus.

In 1991's Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture, Spong argues that St. Paul was homosexual, a theme that was satirized in Gore Vidal's novel Live from Golgotha.

"Points for Reform" of Christianity

Spong's "Twelve Points for Reform" were originally published in The Voice, the newsletter of the Diocese of Newark, in 1998.[13] Spong elaborates on them in his book A New Christianity for a New World:

- Theism, as a way of defining God, is dead. So most theological God-talk is today meaningless. A new way to speak of God must be found.

- Since God can no longer be conceived in theistic terms, it becomes nonsensical to seek to understand Jesus as the incarnation of the theistic deity. So the Christology of the ages is bankrupt.

- The Biblical story of the perfect and finished creation from which human beings fell into sin is pre-Darwinian mythology and post-Darwinian nonsense.

- The virgin birth, understood as literal biology, makes Christ's divinity, as traditionally understood, impossible.

- The miracle stories of the New Testament can no longer be interpreted in a post-Newtonian world as supernatural events performed by an incarnate deity.

- The view of the cross as the sacrifice for the sins of the world is a barbarian idea based on primitive concepts of God and must be dismissed.

- Resurrection is an action of God. Jesus was raised into the meaning of God. It therefore cannot be a physical resuscitation occurring inside human history.

- The story of the Ascension assumed a three-tiered universe and is therefore not capable of being translated into the concepts of a post-Copernican space age.

- There is no external, objective, revealed standard written in scripture or on tablets of stone that will govern our ethical behavior for all time.

- Prayer cannot be a request made to a theistic deity to act in human history in a particular way.

- The hope for life after death must be separated forever from the behavior control mentality of reward and punishment. The Church must abandon, therefore, its reliance on guilt as a motivator of behavior.

- All human beings bear God's image and must be respected for what each person is. Therefore, no external description of one's being, whether based on race, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, can properly be used as the basis for either rejection or discrimination.

Criticism

Spong claims that his writings simultaneously evoke great support and great condemnation from differing segments of the Christian church.[14]

New Testament scholar Raymond E. Brown was critical of Spong's scholarship, referring to his studies as "amateur night".[15] Spong frequently praised Brown's scholarship, though the affection was not returned, with Brown commenting that "Spong is complimentary in what he writes of me as a NT scholar;...I hope I am not ungracious if in return I remark that I do not think that a single NT author would recognize Spong’s Jesus as the figure being proclaimed or written about."[16]

Spong's ideas have been criticized by some other theologians, notably in 1998 by Rowan Williams, the Bishop of Monmouth, who later became the Archbishop of Canterbury. Williams described Spong's Twelve Points for Reform as embodying "confusion and misinterpretation".[17]

During a speaking tour in Australia in 2001, Spong was banned by Peter Hollingworth, the Archbishop of Brisbane, from speaking at churches in the diocese. The tour coincided with Hollingworth leaving the diocese to become the Governor-General of Australia. Hollingworth said that it was not an appropriate moment for Spong to "engage congregations in matters that could prove theologically controversial".[18][19] After Spong's book Jesus for the Non-Religious was published in 2007, Peter Jensen, the Archbishop of Sydney, banned Spong from preaching at any churches in his diocese. By contrast, Phillip Aspinall, the Primate of Australia, invited Spong in 2007 to deliver two sermons at St. John's Cathedral, Brisbane.[20]

Mark Tooley, a Methodist who is president of the Institute on Religion and Democracy, a think tank noted for its critique of liberal religious groups, criticized Spong in 2010 as "brandishing the stale theologies and ideologies of a half-century ago".[21]

Michael Bott, former vice-president of the Wellington Christian Apologetics Society in New Zealand, and Jonathan Sarfati, editorial consultant for Creation Ministries International, criticized Spong's scholarship in an article published by the Apologetics Society's journal in 1995 and updated in 2007, saying he "views the world through the eyes of 19th century rationalism."[22]

Albert Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has condemned Spong as a heretic, claiming that he has "denied virtually every major Christian doctrine".[23]

Publications

- 1973 – Honest Prayer, ISBN 1-878282-18-2

- 1974 – This Hebrew Lord, ISBN 0-06-067520-9

- 1975 – Christpower, ISBN 1-878282-11-5

- 1975 – Dialogue: In Search of Jewish-Christian Understanding (co-authored with Rabbi Jack Daniel Spiro), ISBN 1-878282-16-6

- 1976 – Life Approaches Death: A Dialogue on Ethics in Medicine

- 1977 – The Living Commandments, ISBN 1-878282-17-4

- 1980 – The Easter Moment, ISBN 1-878282-15-8

- 1983 – Into the Whirlwind: The Future of the Church, ISBN 1-878282-13-1

- 1986 – Beyond Moralism: A Contemporary View of the Ten Commandments (co-authored with Denise G. Haines, Archdeacon), ISBN 1-878282-14-X

- 1987 – Consciousness and Survival: An Interdisciplinary Inquiry into the Possibility of Life Beyond Biological Death (edited by John S. Spong, introduction by Claiborne Pell), ISBN 0-943951-00-3

- 1988 – Living in Sin? A Bishop Rethinks Human Sexuality, ISBN 0-06-067507-1

- 1991 – Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture, ISBN 0-06-067518-7

- 1992 – Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus, ISBN 0-06-067523-3

- 1994 – Resurrection: Myth or Reality? A Bishop's Search for the Origins of Christianity, ISBN 0-06-067546-2

- 1996 – Liberating the Gospels: Reading the Bible with Jewish Eyes, ISBN 0-06-067557-8

- 1999 – Why Christianity Must Change or Die: A Bishop Speaks to Believers In Exile, ISBN 0-06-067536-5

- 2001 – Here I Stand: My Struggle for a Christianity of Integrity, Love and Equality, ISBN 0-06-067539-X

- 2002 – God in Us: A Case for Christian Humanism (with Anthony Freeman), ISBN 978-0907845171

- 2002 – A New Christianity for a New World: Why Traditional Faith Is Dying and How a New Faith Is Being Born, ISBN 0-06-067063-0

- 2005 – The Sins of Scripture: Exposing the Bible's Texts of Hate to Reveal the God of Love, ISBN 0-06-076205-5

- 2007 – Jesus for the Non-Religious, ISBN 0-06-076207-1

- 2009 – Eternal Life: A New Vision: Beyond Religion, Beyond Theism, Beyond Heaven and Hell, ISBN 0-06-076206-3

- 2011 – Re-Claiming the Bible for a Non-Religious World, ISBN 978-0-06-201128-2

- 2013 – The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic, ISBN 978-0-06-201130-5

- 2016 – Biblical Literalism: A Gentile Heresy, ISBN 978-0-06-236230-8

- 2018 – Unbelievable: Why Neither Ancient Creeds Nor The Reformation Can Produce a Living Faith Today, ISBN 0-06-264129-8

References

- Interview. ABC Radio Australia, June 17, 2001

- John Shelby Spong, The Sins of Scripture, HarperCollins 2005, page xi

- The General Convention of the Episcopal Church: House of Bishops Archived 2014-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "The retired Bishop John Shelby Spong interview", Read the Spirit website, 23 June 2013.

- "The Humanist Foundation". Churchofhumanism.org. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- Speaking calendar

- Question & Answer Archived 2015-07-23 at the Wayback Machine (paragraph 3) johnshelbyspong.com, 23 July 2015.

- "Former Newark Episcopal bishop Spong suffers stroke". NJ.com.

- "Challenging the 'Sins of Scripture'". Interview with Bill O'Reilly. April 14, 2005.

- Shelby, John (2010-11-05). "Dominus Iesus: The Voice of Rigor Mortis". Beliefnet.com. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- Liberal Bible-Thumping The New York Times, May 15, 2005

- Q & A for 2-14-2013 – electronic newsletter, A New Christianity For a New World, http://johnshelbyspong.com/

- A Call for a New Reformation

- Spong, John Shelby (2000) Here I Stand: My Struggle for a Christianity of Integrity, Love and Equality (Harper Collins), pp. 1–2.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997). An Introduction to the New Testament. Doubleday.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1992). The Birth of the Messiah: a commentary on the infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke. Doubleday.

- Williams, Rowan (1998-07-17). "No life, here – no joy, terror or tears". Church Times. Anglican Ecumenical Society.

- "Anglican Church snubs Bishop". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 Jun 2001. Retrieved 5 Jan 2016.

- "Fear of ideas: The decline and fall of Anglicanism". The Guardian. 7 Jul 2001. Retrieved 5 Jan 2016.

- "Sydney Archbishop Jensen bans John Shelby Spong". The Australian. 14 Aug 2007. Retrieved 5 Jan 2016.

- Tooley, Mark (March 25, 2010). "My Evening with Bishop John Shelby Spong". www.catholicity.com. InsideCatholic.com. Retrieved 23 Aug 2014.

- What’s Wrong With Bishop Spong? Laymen Rethink the Scholarship of John Shelby Spong

- Heresy in the Cathedral