John Harding, 1st Baron Harding of Petherton

Field Marshal Allan Francis Harding, 1st Baron Harding of Petherton, GCB, CBE, DSO & Two Bars, MC (10 February 1896 – 20 January 1989), known as John Harding, was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First World War and the Second World War, served in the Malayan Emergency, and later advised the British government on the response to the Mau Mau Uprising. He also served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the British Army, and was Governor of Cyprus from 1955 to 1957 during the Cyprus Emergency.

The Lord Harding of Petherton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 February 1896 South Petherton, Somerset |

| Died | 20 January 1989 (aged 92) Nether Compton, Dorset |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1955 |

| Rank | Field marshal |

| Service number | 12247 |

| Commands held | Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1952–55) British Army of the Rhine (1951–52) Far East Land Forces (1948–51) Southern Command (1947–48) XIII Corps (1945) VIII Corps (1943–44) 7th Armoured Division (1942–43) 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry (1939–40) |

| Battles/wars | First World War Second World War Malayan Emergency Cyprus Emergency |

| Awards | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Commander of the Order of the British Empire Distinguished Service Order & Two Bars Military Cross Mentioned in Despatches Commander of the Legion of Merit (United States) |

| Relations | John Harding, 2nd Baron Harding (son) |

Early life and First World War

Born the son of Francis Ebenezer Harding and Elizabeth Ellen Harding (née Anstice) and educated at Ilminster Grammar School and King's College London,[1] Harding started as a boy clerk in December 1911,[2] earning promotion to assistant clerk in the Post Office in July 1913[3] and then to full clerk in the Second Division of the Civil Service in April 1914.[4]

Harding became a part-time soldier, joining the 11th (County of London) Battalion (Finsbury Rifles) of the London Regiment, a unit of the British Army's Territorial Force, being commissioned as a second lieutenant on 15 May 1914.[5][6] During the First World War (1914–1918) he was attached to the Machine Gun Corps and fought in the Gallipoli Campaign in August 1915.[5] He transferred to the regular armed forces as a lieutenant in the Somerset Light Infantry on 22 March 1917 and was assigned to the Middle Eastern theatre of operations.[7] He took part in the Third Battle of Gaza in November 1917 and was subsequently awarded the Military Cross.[8]

During the interwar period Harding adopted the name "John", which his Regular Army comrades preferred, and in 1921 was posted to India.[7][6] Promoted to captain on 11 October 1923 and later attended the Staff College, Camberley. He joined the general staff at headquarters Southern Command in 1930 before becoming brigade major of the 13th Infantry Brigade in 1933.[7] He became a company commander with the 2nd Battalion with promotion to major on 1 July 1935.[7] After a tour as a staff officer in the Directorate of Operations at the War Office, he was further promoted to lieutenant colonel on 1 January 1938.[7]

Second World War

Harding served in the Second World War, initially as Commanding Officer (CO) of the 1st Battalion, Somerset Light Infantry, in which capacity he served in Waziristan and was mentioned in despatches,[9] before joining the staff of Middle East Command in October 1940 and then becoming a brigadier General Staff (BGS) of the Western Desert Force (WDF) in December.[10][11] He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for services in that role.[12][11] When Generals Richard O'Connor and Philip Neame were captured in April 1941, Harding took temporary command of the WDF, in which capacity he took the decision to hold Tobruk.[13] He was promoted to the substantive rank of colonel on 9 August 1941 (with seniority backdated to 1 January 1941)[14] and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).[15]

Harding went on to be BGS of XIII Corps (the new name adopted by the former WDF) in August 1941 and, having been mentioned in dispatches in early 1942[16] and awarded a Bar to his DSO in February 1942.[17] He was promoted to acting major-general on 26 January 1942[18] and became Deputy Director of Military Training Middle East Command,[13] in which capacity he was again mentioned in despatches in the summer of 1942.[19][13]

He was appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 7th Armoured Division in September 1942.[10] He led the division in the Second Battle of El Alamein in October–November.[20] He led his forward headquarters from a tank and then a jeep and, during the pursuit of the Axis forces to Tripoli, was subsequently wounded by shell splinters in January 1943.[10][20] He was awarded a second Bar to his DSO for his conduct in late January 1943.[21] At the same time his rank of major-general was made temporary.[22]

He returned to the United Kingdom and, despite losing three fingers from his left hand, recovered relatively quickly. On 10 November 1943 he was promoted to acting lieutenant general[23] and assumed command of VIII Corps, which was to take part in the invasion of Normandy.[20] Soon afterwards, however, he was posted to the Italian Front in January 1944 to become Chief of Staff to General Sir Harold Alexander, then commanding the 15th Army Group, later designated the Allied Armies in Italy (AAI) before reverting to 15th Army Group in December 1944.[10] He was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath on 16 June 1944 for his service in Italy,[24] and promoted to the substantive rank of major general on 13 July 1944.[25] He played a large part in the planning for Operation Diadem, the Fourth and final Battle of Monte Cassino and led to the capture of Rome and the destruction of a large portion of the enemy's forces and the subsequent fighting on the Gothic Line.[26] He went on to take command of XIII Corps in Italy in March 1945,[26] leading it through the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy, arriving in Trieste just after the German surrender in May and the end of World War II in Europe.[10] He was also awarded the Legion of Merit in the Degree of Commander by Harry S. Truman, the President of the United States, for his conduct during the war on 14 May 1948.[27]

Postwar

Promoted after the war to lieutenant general on 19 August 1946,[28] Harding succeeded Alexander as commander of British forces in the Mediterranean in November 1946.[10] He became General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) Southern Command in July 1947 and went on to be Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C), Far East Land Forces on 28 July 1949[29] at the early stages of the Malayan Emergency.[1] Having been promoted to full general on 9 December 1949,[30] made Aide-de-Camp General to H.M. The King on 21 October 1950[31] and advanced to a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the King's Birthday Honours 1951,[32] Harding became Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) on 30 August 1951.[33][34]

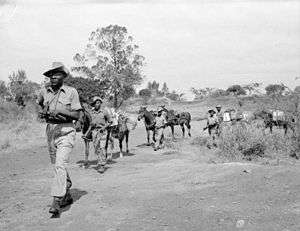

Harding was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) on 1 November 1952:[35] in this capacity he advised the British government on the response to the Mau Mau Uprising.[1] He was promoted to field marshal on 21 July 1953,[36] and retired from the army on 29 September 1955.[37]

Harding was also Colonel of the North Somerset Yeomanry from 2 February 1949,[38] Colonel of the 6th Queen Elizabeth's Own Gurkha Rifles from 18 May 1951 (to 1961),[39] Colonel of the Somerset Light Infantry from 13 April 1953,[40] Colonel of the Life Guards from 26 April 1957[41] and Colonel of the Somerset and Cornwall Light Infantry from 6 October 1959.[42]

Cyprus and later career

On 3 October 1955, Harding was assigned the post of Governor of the British colony of Cyprus. As Governor of Cyprus, Harding sought to restore the relations with the United Kingdom, by negotiating with both the Greek-Cypriot and the Turkish-Cypriot communities on the island, while the British Government was negotiating with the Greek and Turkish governments. Harding took strict measures to improve the security situation in Cyprus, EOKA having declared an armed struggle against the British on 1 April 1955. To this end, Harding instituted a number of unprecedented measures including curfews, closures of schools, the opening of concentration camps, the indefinite detention of suspects without trial and the imposition of the death penalty for offences such as carrying weapons, incendiary devices or any material that could be used in a bomb. A number of such executions took place often in controversial circumstances (e.g. Michalis Karaolis) leading to resentment, in Cyprus, the United Kingdom and in other countries.[43][44]

Implementing the policy of the British Government, Harding also attempted to use negotiations to end the Cyprus crisis. However, negotiations with Archbishop Makarios III were unsuccessful and, eventually, Harding exiled Makarios to the British colony of Seychelles. On 21 March 1956 EOKA made an assassination attempt on Harding's life which failed as the time bomb under his bed failed to go off.[45][46] It was not long after this that Harding offered a reward of £10,000 for General George Grivas, the leader of EOKA.[47]

Facing growing criticism in the United Kingdom about the methods he used and their lack of effectiveness, Sir John Harding resigned as Governor of Cyprus on 22 October 1957 and was replaced by Sir Hugh Foot.[48]

In January 1958, Harding was created Baron Harding of Petherton.[33] In retirement he became Non-Executive Chairman of Plessey[1] as well being the first Chairman of the Horse Race Betting Levy Board.[33] His interests included his membership of the Finsbury Rifles Old Comrades Association in which he participated until late in his life.[33] He died at his home in Nether Compton in Dorset on 20 January 1989.[1]

Family

In 1927 he married Mary Rooke; they had one son:[7] John Charles Harding, 2nd Baron Harding of Petherton.[49]

Arms

|

|

References

- "John Harding". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "No. 28568". The London Gazette. 2 January 1912. p. 38.

- "No. 28734". The London Gazette. 4 July 1913. p. 4748.

- "No. 28828". The London Gazette. 5 May 1914. p. 3676.

- Heathcote, Anthony p. 167

- Holmes, p. 109.

- Heathcote, Anthony p. 168

- "No. 30514". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 February 1918. p. 1802.

- "No. 35195". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 June 1941. p. 3496.

- Heathcote, Anthony p. 169

- Mead, p. 191

- "No. 35209". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 July 1941. p. 3882.

- Mead, p. 192

- "No. 35250". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 August 1941. p. 4789.

- "No. 35396". The London Gazette. 26 December 1941. p. 7333.

- "No. 35821". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 December 1942. p. 5437.

- "No. 35465". The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 February 1942. p. 893.

- "No. 35448". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 February 1942. p. 645.

- "No. 36065". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 June 1943. p. 2853.

- Mead, p. 193

- "No. 35879". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 January 1943. p. 524.

- "No. 35935". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 March 1943. p. 1179.

- "No. 36253". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 November 1943. p. 5068.

- "No. 36564". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 June 1944. p. 2857.

- "No. 36616". The London Gazette (Supplement). 18 July 1944. p. 3379.

- Mead, p. 194

- "No. 38288". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 May 1948. p. 2917.

- "No. 37701". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 August 1946. p. 4295.

- "No. 38727". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 September 1949. p. 4723.

- "No. 38778". The London Gazette (Supplement). 9 December 1949. p. 5828.

- "No. 39060". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 November 1950. p. 5541.

- "No. 39243". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1951. p. 3062.

- Heathcote, Anthony pg 170

- "No. 39334". The London Gazette (Supplement). 14 September 1951. p. 4867.

- "No. 39689". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 November 1952. p. 5863.

- "No. 39916". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 July 1953. p. 3985.

- "No. 40598". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 September 1955. p. 5555.

- "No. 38530". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 February 1949. p. 633.

- "No. 39313". The London Gazette (Supplement). 21 August 1951. p. 4432.

- "No. 39811". The London Gazette (Supplement). 27 March 1953. p. 1783.

- "No. 41054". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 April 1957. p. 2507.

- "No. 41834". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 October 1959. p. 6270.

- "Deepening Tragedy". Time Magazine. 21 May 1956. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Grivas (1964)

- "The Field Marshal's Pea". Time Magazine. 2 April 1956. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Grivas (1964), p. 68 & 69.

- Grivas (1964), p. 69

- "Time for a change". Time Magazine. 4 November 1957. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- "Burke's Peerage". Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Debrett's Peerage. 1973.

Sources

- Grivas, George (1964). The Memoirs of General Grivas edited by Charles Foley. Longmans, London. ASIN B0006DASLW.

- Heathcote, Tony (1999). The British Field Marshals 1736–1997. Barnsley (UK): Pen & Sword. ISBN 0-85052-696-5.

- Holmes, Richard (2011). Soldiers: Army Lives and Loyalties from Redcoats to Dusty Warriors. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-722570-5.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A Biographical Guide to the Key British Generals of World War II. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Harding, 1st Baron Harding of Petherton. |

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Renton |

GOC 7th Armoured Division 1942–1943 |

Succeeded by George Erskine |

| Preceded by Richard McCreery |

GOC VIII Corps 1943–1944 |

Succeeded by Richard O'Connor |

| Preceded by Sidney Kirkman |

GOC XIII Corps March – May 1945 |

Post disbanded |

| Preceded by Sir John Crocker |

GOC-in-C Southern Command 1947–1948 |

Succeeded by Sir Ouvry Roberts |

| Preceded by Sir Neil Ritchie |

C-in-C Far East Land Forces 1948–1951 |

Succeeded by Sir Charles Keightley |

| Preceded by Sir Charles Keightley |

C-in-C British Army of the Rhine 1951–1952 |

Succeeded by Sir Richard Gale |

| Preceded by Sir William Slim |

Chief of the Imperial General Staff 1952–1955 |

Succeeded by Sir Gerald Templer |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Robert Armitage |

Governor of Cyprus 1955–1957 |

Succeeded by Sir Hugh Foot |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baron Harding of Petherton 1958–1989 |

Succeeded by John Charles Harding |