Jean Alfonse

Jean Fonteneau, dit Alfonse de Saintonge (also spelled Jean Allefonsce) or João Afonso in Portuguese (also spelled João Alfonso) (c. 1484, Portugal – December 1544 or 1549, off La Rochelle) was a Portuguese navigator,[1][2][3] explorer and corsair, prominent in the European age of discovery. He had an early career in Portugal and later served the King of France.

Jean Alfonse | |

|---|---|

| Born | Jean Fonteneau, dit Alfonse de Saintonge c. 1484 |

| Died | December 1544 (aged 60) or December 1549 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | Portuguese and French |

| Occupation | navigator, explorer and corsair |

Early years and Personal life

Born João Afonso and later known in France as Jean Fonteneau or Alfonse of Saintonge, he married a woman named Victorine Alfonse (Victorina Alfonso). Taking to the sea at age 12, he joined the Portuguese India Armadas and the Portuguese commercial fleets as they sailed past the seven seas to the coasts of Brasil, Western Africa, and around the Cape to Madagascar and Asia. His writings talk of days lasting three months, and of a vast southern continent, the Terra Australis, and the Jave la Grande, which he claims to have seen south of Southeast Asia, possibly suggesting he had approached the Arctic (by North America), Australia, and Antarctica.

In service of France

Before or around 1530, for some reasons, he moved to France putting himself at the service of Francis I. The correspondence of diplomatic agents of the king of Portugal in France, in the first half of the century, tried to clarify the causes of this change of allegiance. Gaspar Palha, a Portuguese diplomat in Paris in 1531, having met a man from La Rochelle to whom he requested information concerning the pilot Jean Alfonse, wrote that he had been exiled because, when he was lost near the coast of Brittany hit by a storm, he had been involved in a quarrel (according to what was reported, with his own oldest son) that resulted in the death of his son or some man aboard; and that consequently he had been exiled and did not dare to appear in public, but it is a report by indirect testimony, and there may have been other non-criminal reasons for the exile. However, it appears that it was to escape the Portuguese Justice for some reason. Jean Alfonse left the country, later in the company of his wife and his sons. In 1531, John III attempted to repatriate the defector pilot because of his high qualifications and for his vast and possible classified knowledge.[4] The king himself corresponded directly with Afonso, sending letters of pardon by his ambassadors and representatives and later exchanging letters with him in this attempt.

By the 1540s, he was a renowned pilot, leading fleets to Africa and the Caribbean and reputed to have never lost a ship. André Thévet mentions a conversation where Alfonse described looting Puerto Rico as a corsair. It was long thought that the Rabelaisian hero Xenomanes was based on Alfonse.

In 1542-43, Alfonse piloted Jean-François de la Roque de Roberval's attempt to colonize Canada on the heels of Jacques Cartier's third voyage there. Alfonse established that one could sail through a passage between Greenland and Labrador. The crew of 200, including prisoners and a few women, spent a harsh winter on the shores of the St. Lawrence River, hit by scurvy and losing a quarter of the colonists before sailing back to France. During this trip, Alfonse described a land he called Norombega.[5]

In late 1544, Alfonse left La Rochelle with a small fleet and disrupted Basque shipping, while the treaty of Crépy had just been signed between France and Spain. A Spanish fleet led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés caught up to him as he was getting back to La Rochelle and killed him at sea. Some sources say this fatal encounter occurred in 1549.[6]

Works

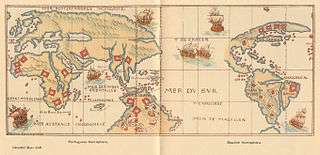

His writings were published as Les voyages avantureux du Capitaine Ian Alfonce (1559), the Rutter of Jean Alphonse (1600) and La cosmographie avec l’espère et régime du soleil du nord par Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge, capitaine-pilote de François Ier (1904). In them he describes the various places and peoples he and others have seen, many of them for the first time in print (such as Gaspé, the Beothuk, Saint-Pierre Island, the jewels of Madagascar, a continent south of Java) and provides navigational instructions on how to get there. [[Image:Australia first map.jpg|thumb|360px|center|Jave La Grande's east coast: from Nicholas Vallard's atlas, 1547. Copy held by the National Library of Australia]

References

- Pinheiro Marques, Alfredo (1998). "A cartografia do Brasil no século XVI". Centro de Estudos de Historia e Cartografia Antiga (Instituto de Investigaçao Cientifica Tropical : Col·lecció) Separatas. 209, Centro de estudos de história e de cartografia antiga - Série Separatas (UC Biblioteca Geral 1, 1988): 449.

- The Great Circle: Journal of the Australian Association for Maritime History, Volumes 6-9, Australian Association for Maritime History - The Association, 1984, University of Virginia

- Luis Filipe F. R. Thomaz, The image of the Archipelago in Portuguese cartography of the 16th and early 17th centuries, Persee, 1995, Volume 49 pages: 79-124

- DÉPARTEMENT D'HISTOIRE ET DE SCIENCES POLITIQUES, Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines Université de Sherbrooke DU CIEL AU BATEAU. LA COSMOGRAPHIE (1544) DU PILOTE JEAN ALFONSE ET LA CONSTRUCTION DU SAVOIR GÉOGRAPHIQUE AU XVI SIÉCLE. Dany Larochelle Bachelier en éducation (B.Ed.) de l'université du Québec à Trois-Rivières - MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ pour obtenir LA MAÎTRISE ES ARTS (HISTOIRE), National Library of Canada / Bibliothèque Nationale du Canada, Sherbrooke, April 2011 Page 4.

- DeCosta, 1890, p. 99.

- Philip P. Boucher, France and the American tropics to 1700, JHU Press, 2008, p. 49.

- Charles de la Roncière, Histoire de la marine française, tome 3, Les guerres d'Italie: liberté des mers. Paris, Plon, 1906. p. 222-333.

- Marcel Trudel, Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, vol. 1, Les vaines tentatives. Montréal and Paris, Fides, 1963, p. 157-175.

- Nicolas Dedek, La cosmographie de Jean Alfonse de Saintonge: représentation du monde et de l'État à la Renaissance, Montréal, Université du Québec à Montréal, 2000.