Chinese jade

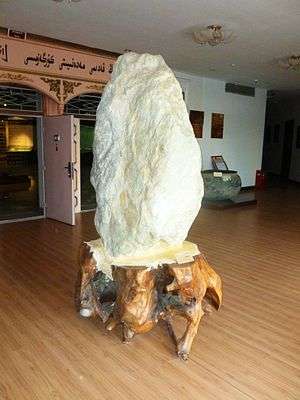

Chinese jade refers to the jade mined or carved in China from the Neolithic onward. It is the primary hardstone of Chinese sculpture. Although deep and bright green jadeite is better known in Europe, for most of China's history, jade has come in a variety of colors and white "mutton-fat" nephrite was the most highly praised and prized. Native sources in Henan and along the Yangtze were exploited since prehistoric times and have largely been exhausted; most Chinese jade today is extracted from the northwestern province of Xinjiang.

Jade was prized for its hardness, durability, magical qualities, and beauty.[1] In particular, its subtle, translucent colors and protective qualities[1] caused it to become associated with Chinese conceptions of the soul and immortality.[2] With gold, it was considered to be a symbol of heaven.[3] The most prominent early use was the crafting of the Six Ritual Jades, found since the 3rd-millennium BC Liangzhu culture:[4] the bi, the cong, the huang, the hu, the gui, and the zhang.[5] Since the meanings of these shapes were not mentioned prior to the eastern Zhou dynasty, by the time of the composition of the Rites of Zhou, they were thought to represent the sky, the earth, and the four directions.[6] By the Han dynasty, the royal family and prominent lords were buried entirely ensheathed in jade burial suits sewn in gold thread, on the idea that it would preserve the body and the souls attached to it. Jade was also thought to combat fatigue in the living.[1] The Han also greatly improved prior artistic treatment of jade.[7]

These uses gave way after the Three Kingdoms period to Buddhist practices and new developments in Taoism such as alchemy. Nonetheless, jade remained part of traditional Chinese medicine and an important artistic medium. Although its use never became widespread in Japan, jade became important to the art of Korea and Southeast Asia.

Name

The Chinese word yù 玉 "jade; gems of all kinds; (of women) beautiful; (courteous) your" has semantically broader meanings than English jade "any of various hard greenish gems used in jewelry and artistic carvings, including jadeite and nephrite; a green color of medium hue; made of jade; green like jade".[8][9] Yù has referred to many rocks and minerals that carve and polish well, especially jadeite, nephrite and agalmatolite, as well as bowenite and other varieties of serpentine.[10] Jadeite is now known as yìngyù 硬玉 (lit. "hard jade") and nephrite correspondingly as ruǎnyù 軟玉 (lit. "soft jade"). The polysemous term yù is used in various Chinese chengyu "set phrases, such as pāozhuānyǐnyù 抛砖引玉 (lit. "cast aside a brick, pick up a jade") "offer banal/humble remarks to spark abler talk by others; sacrifice a little to gain much"—one of the Thirty-Six Stratagems, and idioms, for instance yùlì 玉立 (lit. "jade standing") "gracious; graceful".

The Chinese character 玉 for yu "jade" dates back to circa 11th century BCE oracle bone script from the late Shang dynasty, when it depicted pieces of jade hanging on a string. Chinese characters most commonly combine a radical, such as the "jade radical" 玉 or 王, that suggests meaning and a phonetic that hints at pronunciation. The "jade radical" frequently occurs in characters for names of gemstones (e.g., bì 碧 "green jade; bluish green" and shānhú 珊瑚 "coral"), and occasionally for words denoting "preciousness" (bǎo 宝 "treasure" and bǎobǎo 宝宝 "precious/darling baby").

History

_MET_DT204.jpg)

Jade has been used in virtually all periods of Chinese history and generally accords with the style of decorative art characteristic of each period. Its deep significance in Chinese culture has deemed it worthy of being symbolic of ancient Chinese ethics and ideologies and also representative of the progression of Chinese culture.[11] Thus, the earliest jades, of the Neolithic Period, are unornamented ritual and impractical versions of the tools and weapons that were in ordinary use, often much larger than normal examples. These are presumed to have been symbols of political power or possibly religious authority.[12]

There have been three main Neolithic jadeworking centers.[12] The first known center is known as the Liangzhu culture (c. 3300 – c. 2200).[12] This centre took place in the Lake Tai District.[12] The jades of this period were primarily small items of personal adornment, such as small discs strung onto necklaces.[12] Typically, the jade was polished on its surface and perforated.[12] Ritual jades and personal ornamental jade of different shapes began to show up during this time period.[12] This religious nature of jade is often evaluated as connections between spirituality and the Neolithic societal structure that jade was produced in.[6]

The second centre is known as Longshan culture and arose in 2500 BC.[12] The centre was situated in China's east coast.[12] The jade objects found in these centres were ritualistic implements, such as axes, knives, and chisels.[12] There is a suggestion of curvilinear anthropomorphic images.[12] A distinctive carving technique was used to create the fine raised relief of the anthropomorphic images.[12]

The third known centre is known as the Hongshan culture (c. 3800 – c. 2700 BC).[12] The centre was situated in along the modern northeastern border of China.[12] The objects of this centre were typically pendants and large C-shaped ornaments.[12] Realistic figures of fish, turtles, cicadas, and owl-like birds with spread wings were typical carvings of the Hongshan culture.[12]

During Neolithic times, the key known sources of nephrite jade in China for utilitarian and ceremonial jade items were the now depleted deposits in the Ningshao area in the Yangtze River Delta (Liangzhu culture 3400–2250 BC) and in an area of the Liaoning province in Inner Mongolia (Hongshan culture 4700–2200 BC).[13] Archeological finds have also unearthed jade objects in this province in the shapes of dragons and clay-molded human figurines, therefore symbolizing the existence of a developed social group along the Liao River and inner-Mongolia.[6] As early as 6000 BC, Dushan jade has been mined. In the Yin Ruins of the Shang dynasty in Anyang, Dushan jade ornaments were unearthed in the tombs of the Shang kings.

The bi and cong are types of objects only found in jade in early periods, and probably had religious or cosmic significance. The bi is a circular disk with a hole, originally usually plain, but increasingly decorated, and the cong is a vessel, square on the outside but circular inside. In later literature the cong represents the earth and the bi the sky.

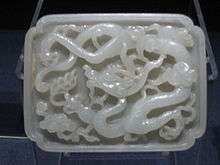

Jades of the Shang, Zhou, and Han dynasties are increasingly embellished with animal and other decorative motifs characteristic of those times, and craftsmen developed great skill in detailed low relief work in objects such as the belt-hooks that became part of elite costume. In later periods ancient jade shapes, derived from bronze sacrificial vessels, and motifs of painting were used to demonstrate the craftsman's extraordinary technical facility.

In the Zhou dynasty (1122–255 BC), the system of government had been completed and there were varying levels of departments within the government. Buttons of jade were utilized to differentiate the various levels of official society.[3]

Jade was used to create many utilitarian and ceremonial objects, ranging from indoor decorative items to jade burial suits, reflecting the ancient Chinese belief that jades would confer immortality or prolong life and prevent decay. Jade spoons, spatulas, and pestles were used to make medicine in order for the jade to bestow its special virtues onto the medical compounds.[3]

From about the earliest Chinese dynasties until the present, jade was sourced from deposits in western regions like Khotan and other parts of China like Lantian, Shaanxi. In Lantian, white and greenish nephrite jade is found in small quarries and as pebbles and boulders in the rivers flowing from the Kun-Lun mountain range northward into the Takla-Makan desert area. River jade collection was concentrated in the Yarkand, the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers. From the Kingdom of Khotan, on the southern leg of the Silk Road, yearly tribute payments consisting of the most precious white jade were made to the Chinese Imperial court and there transformed into objets d'art by skilled artisans as jade was considered more valuable than gold or silver, and white more valuable than green.

Jade became a favorite material for the crafting of Chinese writing materials, such as rests for calligraphy brushes, as well as the mouthpieces of some opium pipes, due to the belief that breathing through jade would bestow longevity upon smokers who used such a pipe.[14]

The Qing dynasty was the final dynasty to gain political power within China, beginning in 1644 until 1911. Emperor Shengzu, who was also known as the Kangxi Emperor, ruled between circa 1662 until 1722. During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, a distinctive pairs of lions or dogs composed of jade were commissioned by the dynastic family.[15]

Carving techniques

The hardness of jade presented an obstacle to those who wanted to carve it and turn it into various objects.[16] In order to quarry nephrite jade, fires were placed next to the jade to heat it and water was thrown against the rock's surface.[16] This rapid temperature change caused the jade to crack and wooden wedges were used to further break it down.[16] However, this quarrying technique also destroyed the jade.[16] The best way to extract jade in terms of it being in the best condition was to remove it from pebbles and boulders that were found in rivers.[16]

Neolithic jade workshops, also known as wasters, have been found in areas where jade usage was evident and popularized.[17] Most evidence of the development of jade technology and tools are taken from wasters and the discards and finished works present in these workshops.[17] From the traces of jade left at these sites, one can see the evolution of crafting procedures from chipping and polishing to more advanced drilling and slicing.[17] Due to the toughness of jade, the chipping and polishing procedures differ drastically from regular stone.[16] The only possible method of altering the shape or texture of this mineral dense rock hasn't seen much change from its introduction to modern day as both times remain reliant on the abrasion method.[16] In order to override the abrasiveness of jade and subdue it to molding, a jade-worker must use an object of higher abrasive factor.[16] In the early days of jade carving, quartz, a mineral with a high hardness level, was the object of choice.[16] At the beginning of the Song dynasty, a time of prolific technology growth, "red sand", with a hardness level of 7.5 became the dominant tool of the industry.[18] By 1939, and once more advanced carving tools had arisen, Peking jade carvers were already using six different types of abrasives: quartz, almandine garnet, corundum, carborundum, diamond, and a medium combining both carborundum and calcareous silt or loess.[19]

In terms of Hongshan (a culture consisting of regions such as Dongjiayingzi, Aohan, and Inner Mongolia) jade, four main tools comprise the basics for jade carving: the string, awl, the hollow drill, and a slow rotating disk.[17] The string tools specifically were involved in the shaping of raw materials and slicing of jade into flat disks.[17] Besides for slicing, this instrument was also responsible for open work, specifically the cutting of slits.[17] Awls and hollow drills were both used to delicately puncture holes into jade material, however, awls were responsible for small pierces in ornaments whereas hollow drills made larger punctures for a variety of purposes.[17] The slow rotating disk, finally, was purposeful in line cutting and preparing jade material for other drilling techniques.[17] Although little is researched regarding the manufacturing techniques of other major Neolithic jade centers Dawenkou or Longshan, the Hongshan culture is quite known for its technical quality in the production of jade products and therefore serves as reliable source when examining the pinnacle of jade crafting during the Neolithic period.[17] The introduction of metal tools occurred in the late Zhou period (1050–256 B.C.).[16] It is likely that the use of copper in these tools preceded the use of iron.[16]

Since jade was considered to be rare and strenuous to work with, pieces of jade were minimally changed and scrap pieces were reused in some way.[16] The microstructure especially, with its composition of densely packed fibrous crystals in a felted mass formation, contributed to the mineral's toughness and difficulty in carving.[19] Due to this toughness and unique manufacturing techniques, the jade objects studied suggest an organized labor structure consisting of skilled laborers and an education in the handling of particular tools.[6] Likewise, stylistic features and carving techniques seen throughout different Chinese cultures suggest a fluid transmission of knowledge between cultures rather than a border-bounded knowledge isolating cultures.[6]

The coloration of the jade was a factor taken into consideration when deciding what form the piece of jade would take.[16]

Categories

Jade objects of early ages (Neolithic through Zhou) fall into five categories: small decorative and functional ornaments such as beads, pendants, and belt hooks; weapons and related equipment; independent sculptural, especially of real and mythological animals; small objects of probably emblematic value, including the han (ornaments, often carved in the shape of a cicada, to be placed in the mouth of the dead), and many examples of larger objects—such as the cong (a hollow cylinder or truncated cone). In terms of the Hongshan culture, bi and cong discs were most common, along with beads, pendants and ornamental pieces for hair and clothing in a variety of animal shapes.[6] Jade manufactured weapons were typical to ritualistic processes like sacrifices and symbols of authority.[6] Particularly axes and blades were seen in the rituals of the Longshan culture.[6]

Six Ritual and Six Ceremonial Jades

The Six Ritual Jades originating in pre-history were the bi (a flat disk with a hole in its center), the cong (prismatic tube),[6] the huang (a flat, half-ring pendant), the hu, the flat, bladelike gui, and the zhang. The original names, value and functions of these objects have invited much speculation. The Zhou Li, itself probably compiled in the Han Dynasty, ascribes the circular bi as representing the heavens, the cong as representing the earth, the gui the east, the zhang the south, the hu the west and the huang the north. Although over two millennia old these names and symbolism were given to these objects by much later writers, who interpreted the objects in a way that reflected their own understanding of the cosmos.

The original use of the "Six Ritual Jades" became lost, with such jades becoming status symbols, with utility and religious significance forgotten. The objects came to represent the status of the holder due to the expense and authority needed to command the resources and labour in creating the object. Thus it was as the "Ceremonial Jades" that the forms of some of these jades were perpetuated. The "Zhou Li" states that a king (wang) was entitled to gui of the zhen type, dukes (gong) to the huang, marquis to gui of the xin type, earls (bo) to gui of the gong type, viscounts (zi) to a bi of the gu type and barons (nan) to a bi of the pu type.

Symbolism and meaning

Jade objects originally begun as forms of spiritual connections or value but in later years, developed into symbols of authority and status.[17] Throughout Neolithic Chinese culture, jade remained, however, saturated in purposeful iconography and symbolism.[6] Especially during the Eastern Zhou period and Shang dynasty, jade objects see representations of celestial beings who played key roles in communicating with ancestral spirits.[6] Later, with the transition to the early Western Zhou period, jade objects began to lose their connectivity to Heavenly powers and instead reflected the political authority and status of their owners.[6] This shift marked an important period in Chinese jade, a correction of usage and thus a redefining of Chinese culture.[6]

Concentration on spirituality

In its earliest states, the visual representations in Chinese jade embody one of the first forms of narrative.[6] Narratives with universal characteristics associated with religion and spirituality utilize natural elements that surround humankind and suggest a religion associated with Heaven and Earth.[6] Due to ancient China's deep dependence on agriculture, and a reliance on a cycle of natural phenomenon, many mystic properties began to be associated with nature.[6] A certain vulnerability when it came to nature, led many to attribute natural phenomena with spirituality. This spirituality, a mythological connection between the mundane Earth and the transcendence of Heaven, was manifested in many jade objects through the late phase of the Shang dynasty.[6] Since jade was extracted from high mountains and riverbeds, and mountains in Chinese culture symbolized a way to ascend beyond the Earth into Heaven, jade held power in terms of funerary rites and other rites associated with mysticism.[20] Funerary ritual jade objects included things like pinnular-shaped ornamental jade, beads, and even agricultural tools such as axes and shovel (used to reiterate the connection between nature and the heavens).[21] These agricultural tools were either placed in tombs as symbols of a prosperous afterlife or to sanctify the tomb for spirits responsible for natural phenomena and human wellbeing.[21] Along with major objects, many smaller animal-shaped objects reflected the same sense of spirituality in nature and remained prevalent throughout the Shang dynasty. Birds, turtles, silkworms, dragons and cicadas appeared the most and each epitomized early China's relationship between religion and nature.[6] Birds flight for instance, symbolized the spiritual journey: a journey from the natural earth to the celestial heavens.[22] Similarly, the turtle's voyage across land and sea represented the expedition from earth to underworld.[23] Jade cicadas and silkworms construed rebirth, symbolizing the rebirth of the dead when placed in tombs.[6]

Along with animal-shaped objects, jade also took upon the shape of clouds, earth, and wind; creating a more literal translation of belief.[24] Cloud pendants and cloud-shaped jade found in tombs of the elite elicit the belief in a hierarchical social structure with leaders holding both political and spiritual power.[25] Bi discs and cong, commonly structured jade objects, also developed funerary significance in their use in rituals.[6] Bi discs, specifically, were used in sacrifices to Heaven.[25] Jade constructed huang pendants likewise saw an important funerary connection due to their inclusion in the typical shaman attire.[6]

Jade human figurines in the Shijiahe culture are another way jade was used in the celestial context. These figurines were supposedly used for the staging of ritual sacrifices and to preserve the memory of the sacrifice for subsequent generations.[20]

Gallery

Bi with two dragons

Bi with two dragons

Warring States

Sculpture of the head and torso of a horse, Han dynasty

Sculpture of the head and torso of a horse, Han dynasty

.jpg)

Cup with dragon handles

Cup with dragon handles

(12th century)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinese jade. |

References

Citations

- Fiero, Gloria K. The Humanistic Tradition 6th Ed, Vol. I. McGraw-Hill, 2010.

- Pope-Henessey, Chapter II.

- D., C. (1921). "CHINESE JADES". Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis. 6: 32–47 – via JSTOR.

- Howard, 19–22

- Pope-Henessey, Chap. IV.

- Lopes, Rui Oliveira (2014). "Securing the Harmony between the High and the Low: Power Animals and Symbols of Political Authority in Ancient Chinese Jades and Bronzes". Asian Perspectives. 53 (2): 195–225. doi:10.1353/asi.2014.0019. hdl:10125/42779. ISSN 1535-8283.

- Watson, 77.

- Wenlin (2016).

- Collins English Dictionary (2011) jade.

- Desautels, Paul E. (1986), The Jade Kingdom, Springer, p. 81.

- "Progress review of the scientific study of Chinese ancient jade". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Rawson, J., Lijun, Z., Sargent, W., Sørensen, H., Blair, S., Bloom, J., Silbergeld, J., Hardie, P., Zheng, H., Steinhardt, N., Ho, P., Pedersen, B., Tanaka, T., Klose, P., Wood, F., Thorp, R., Paludan, A., Wiedehage, P., Michaelson, C., Little, S., Goldberg, S., Zettl, F., Cahill, J., Gyss-Vermande, C., Whitfield, R., Sullivan, M., Bush, S., Robinson, J., Bickford, M., Harrist jr, R., Vinograd, R., Uitzinger, E., Wicks, A., Mackenzie, C., Bagley, R., Xueqin, L., So, J., Wood, N., Medley, M., Vainker, S., Tregear, M., Krahl, R., Mino, Y., Tam, L., Kerr, R., Raindre, G., Pearce, N., Guy, J., Jörg, C., Till, B., Swart, P., Scott, R., Wallis, R., Handler, S., Vollmer, J., Dien, A., Edgren, S., Boda, Y., Cribb, J., Wilson, V., Portal, J., Hong, Z., Wagner, D., Chuimei, H., Nielsen, B., Gyllensvärd, B., Marsh, J., Yee, C., Stephenson, F., Pratt, K., Jurkowski, H., Chapman, J., Lauer, U., Waldram, S., Rutt, R., Kao, M., Li, C., Beurdeley, M., Harrison-Hall, J., Gray, B., & Tao, W. (2003, January 01). China, People's Republic of. Grove Art Online. Ed. Retrieved 3 Dec. 2018, from http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000016513.

- Liu, Li 2003:3–15

- Martin, Steven. The Art of Opium Antiques. Silkworm Books, Chiang Mai, 2007

- "List of Rulers of China". October 4, 2004. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- FitzHugh, E. (2003, January 01). "Jade". Grove Art Online. Ed. Retrieved 26 Nov. 2018, from http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000043200.

- P., Dematte. "The Chinese Jade Age: Between antiquarianism and archaeology". Journal of Social Archaeology. 6 (2): 202–226. doi:10.1177/1469605306064241. ISSN 1469-6053.

- "The Song Dynasty in China". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- Sax, Margaret; Meeks, Nigel D.; Michaelson, Carol; Middleton, Andrew P. (2004-10-01). "The identification of carving techniques on Chinese jade". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (10): 1413–1428. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.03.007. ISSN 0305-4403.

- Nelson, Sarah (1995). The archaeology of northeast China : beyond the Great Wall. London: Routledge. pp. 21–64.

- Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2008), "Sociopolitical Change from Neolithic to Bronze Age China", Archaeology of Asia, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 149–176, doi:10.1002/9780470774670.ch8, ISBN 9780470774670

- Bachelard, Gaston (1943). L'air et les songes. Essai sur l'imagination du mouvement. Paris: Librairie José Corti.

- Liu, Li (2004). The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–67.

- Childs-Johnson, Elisabeth (1988). "Dragons, masks, axes and blades from four newly documented jade-working cultures of Ancient China". Orientation. 19: 30–41.

- Teng, Shu P'ing (2000). "The original significance of bi disks: insights based on Liangzhu jade bi with incised symbolic motifs". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 2: 165–194. doi:10.1163/156852300509835.

Bibliography

- Howard, Angela Falco, Chinese sculpture, Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-300-10065-5, ISBN 978-0-300-10065-5. Google books

- Pope-Hennessy, Una, Early Chinese Jades, reprint edn. READ BOOKS, 2008, ISBN 1-4437-7158-9, ISBN 978-1-4437-7158-0 Google books

- Scott-Clark, Cathy and Levy, Adrian. (2002) The Stone of Heaven: Unearthing the Secret History of Imperial Green Jade. ISBN 0-316-52596-0

- Watson, William, & Ho, Chuimei. The arts of China after 1620, Yale University Press Pelican history of art, Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-300-10735-8, ISBN 978-0-300-10735-7

Further reading

- Laufer, Berthold, 1912, Jade: A Study in Chinese Archeology & Religion, Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1974.

- Rawson, Jessica, 1975, Chinese Jade Throughout the Ages, London: Albert Saifer, ISBN 0-87556-754-1

- Art in Quest of Heaven and Truth: Chinese Jades through the Ages. Taipei: National Palace Museum.

- Between hell and the Stone of Heaven: Observer article on Jade Mining in Burma

- Old Chinese Jades: Real or Fake?

- BOOK REVIEW, The Stone of Heaven: The Secret History of Imperial Green Jade by Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark