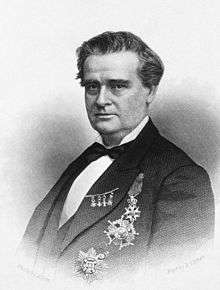

J. Marion Sims

James Marion Sims (January 25, 1813 – November 13, 1883) was an American physician and a pioneer in the field of surgery, both known as the "father of modern gynaecology" and as a controversial figure for the ethical approach to developing his techniques.[3] His most significant work was the development of a surgical technique for the repair of vesicovaginal fistula, a severe complication of obstructed childbirth.[4] He is also remembered for inventing Sims' speculum, Sims' sigmoid catheter, and the Sims' position. However, as medical ethicist Barron H. Lerner states, "one would be hard pressed to find a more controversial figure in the history of medicine."[5]

J. Marion Sims | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 25, 1813[1] |

| Died | November 13, 1883 (aged 70)[2] Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Jefferson Medical College |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

| Spouse(s) | Theresa Jones |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

Sims perfected his surgical techniques by operating without anesthesia on enslaved black women.[3][5] In the 20th century, this was condemned as an improper use of human experimental subjects and Sims was described as "a prime example of progress in the medical profession made at the expense of a vulnerable population".[3] Sims' practices were defended as consistent with the era in which he lived by physician and anthropologist L. Lewis Wall,[6] and according to Sims, the enslaved black women were "willing" and had no better option.[5]

Sims was a voluminous writer and his published reports on his medical experiments, together with his own 471-page autobiography (summarized by Wylie[7]), have been the main sources of knowledge about him and his career. His positive self-presentation has, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, been subject to revision.

Early life, education and career

J. Marion Sims (called Marion) was born in Lancaster County, South Carolina,[8] the son of John and Mahala (Mackey) Sims. For his first 12 years, Sims's family lived in Lancaster Village north of Hanging Rock Creek, where his father owned a store. Sims later wrote of his early school days there.[7]:4–5

After his father was elected as sheriff of Lancaster County, he sent Sims in 1825 to the newly established Franklin Academy, in Lancaster (for white boys only). In 1832, after two years of study at the predecessor of the University of South Carolina, South Carolina College, where he was a member of the Euphradian Society, Sims worked with Dr. Churchill Jones in Lancaster, South Carolina. He took a three-month course at the Medical College of Charleston (predecessor of the Medical University of South Carolina).

He moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1834 and enrolled at the Jefferson Medical College, where he graduated in 1835, "a lackluster student who showed little ambition after receiving his medical degree".[5] As he put it,

I felt no particular interest in my profession at the beginning of it apart from making a living.... I was really ready at any time and at any moment to take up anything that offered, or that held out any inducement of fortune, because I knew that I could never make a fortune out of the practice of medicine.[7]:8

He returned to Lancaster to practice. After his first two patients died, Sims left and set up a practice in Mount Meigs, near Montgomery, Alabama.[7]:7 He described the settlement in a letter to his future wife Theresa Jones as "nothing but a pile of gin-houses, stables, blacksmith-shops, grog-shops, taverns and stores, thrown together in one promiscuous huddle".[9]:374 He was in Mount Meigs from 1835 to 1837.[10]:6 Sims visited Lancaster in 1836 to marry Theresa, whom he had met many years earlier, when a student in Lancaster. She was the niece of Churchill Jones, and had studied at the South Carolina Female Collegiate Institute.[9]:177–178[11]

In 1837 Sims and his wife moved to Macon County, Alabama, where they remained until 1840.[10]:6 He was a "plantation physician",[12] who had "a partnership in a large practice among rich plantations."[7]:7 "Sims became known for operations on clubfeet, cleft palates and crossed eyes."[12] This was his first experience treating enslaved women, who were brought to him by their owners.

In 1840 the couple moved to Montgomery, Alabama,[7]:7–8 where they lived until 1853.[10]:10 There Sims had what he described as the "most memorable time" of his career.[13] Within a few years he "had the largest surgical practice in the State", the largest practice that any doctor in Montgomery had ever had, up to that time.[10]:7 "He was immensely popular, and greatly beloved."[10]:8

Medical experimentation on enslaved women

Background

The use of enslaved people for medical research was uncontroversial in the Antebellum South. A prospectus from the 1830s of the South Carolina Medical College, the leading medical school in the South, pointed out to prospective students that it had an advantage of a peculiar character:

No place in the United States offers as great opportunities for the acquisition of anatomical knowledge. Subjects being obtained from among the colored population in sufficient number for every purpose, and proper dissections carried on without offending any individuals in the community.[14]:190

The College announced, in advertisements in the Charleston papers, that it had set up a surgery (operating room) for negroes, and offered to treat without charge, while it was in session, any "interesting cases" sent by their owners, "for the benefit and instruction of their pupils". They extended the offer to free "persons of color".[14]:191 The advertisement ends by pointing out that their "SOLE OBJECT...[was] to promote the interest of Medical Education. "[14]:193

Repair of vesicovaginal fistula

In Montgomery, Sims continued treating enslaved people (who made up two thirds of the city's population[15]:34). He built a hospital for the slaves he bought or rented and kept on his property. [7]:9. It has been called "the first woman's hospital in history".[16] In 1845 he was brought a woman with a condition he had not seen before: vesicovaginal fistula.

In the 19th century, vesicovaginal fistulas, though not fatal, were a common, socially destructive, and "catastrophic complication of childbirth",[6] that affected many women. There was no effective cure or treatment. Lacking adequate birth control, women generally had a high rate of childbirth, which increased their rate of complications.[17] Vesicovaginal fistulas occur when the woman's bladder, cervix, and vagina become trapped between the fetal skull and the woman's pelvis, cutting off blood flow and leading to tissue death. The necrotic tissue later sloughs off, leaving a hole. Following this injury, as urine forms, it leaks out of the vaginal opening, leading to a form of incontinence. Because a continuous stream of urine leaks from the vagina, it is difficult to care for. The victim suffers personal hygiene issues that may lead to marginalization from society, and vaginal irritation, scarring, and loss of vaginal function. Sims also worked to repair rectovaginal fistulas, a related condition in which flatulence and feces escape through a torn vagina, leading to fecal incontinence.[6]

In the mid-19th century, gynecology was not a well-developed field: "the practice of examining the female organs was considered repugnant by doctors." In medical school, doctors were often trained on dummies to deliver babies. They did not see their first clinical cases of women until beginning their practices.[17]:28 Sims had had no formal background in gynecology prior to beginning his practice in Alabama.[7] He remarked in his autobiography that "if there was anything I hated, it was investigating the organs of the female pelvis".[15]:34

When an enslaved woman was brought to him with an injured pelvis from a fall from a horse, he placed her in a knee-chest position and inserted his finger into the vagina. This allowed Sims to see the vagina clearly, and inspired him to investigate fistula treatment.[17][7] Soon after, he developed a precursor to the modern speculum, using a pewter spoon and strategically placed mirrors.[18]

From 1845 to 1849, Sims started doing experiments on enslaved black women to treat vaginal problems. He added a second story to his hospital, for a total of eight beds.[7]:10 He developed techniques that have been the basis of modern vaginal surgery. A key component was silver wire, which he had a jeweler prepare.[19] The Sims' vaginal speculum aided in vaginal examination and surgery. The rectal examination position, in which the patient is on the left side with the right knee flexed against the abdomen and the left knee slightly flexed, is also named for him.

Experimental subjects

In Montgomery, between 1845 and 1849, Sims conducted experimental surgery on 12 enslaved women with fistulas in his backyard hospital.[20] They were brought to him by their enslavers. Sims asked for patients with this fistula, and "succeeded in finding six or seven women".[7]:9 Sims took responsibility for their care on the condition that the owners provide clothing and pay any taxes; Sims provided food.[18] One he purchased "expressly for the purpose of experimentation when her master resisted Sims' solicitations."[15]:35

He named three enslaved women in his records: Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy. Each suffered from fistula, and all were subjects of his surgical experimentation.[5] From 1845 to 1849 he conducted experimental surgery on each of them several times, operating on Anarcha 30 times before the repair of her fistulas was declared a success.[17] She had both vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas, which he struggled to repair.[6] Sims ignored the AMA's Code of Ethics and Jones counsel.[21] "Notwithstanding repeated failures during four years' time, he kept his six patients and operated until he tired out his doctor assistants, and finally had to rely upon his patients to assist him to operate."[7]:10 Unlike his previous essays, which included at least a brief description of his patients, the article issued in The American Journal of the Medical Sciences is devoid of any identifying characteristics of Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy.[21]

Although anesthesia had very recently become available and used experimentally, Sims did not use any anesthetic during his procedures on these three women.[5] According to Sims, anesthesia was not yet fully accepted into surgical practice, and he was unaware of the use of diethyl ether.[6][18] Experimental use of ether as an anesthetic was performed as early as 1842, however it was not published or demonstrated until 1846.[18]

A 2006 review of Sims' work in the Journal of Medical Ethics said that ether anesthesia was first publicly demonstrated in Boston in 1846, a year after Sims began his experimental surgery. The article notes that, while ether's use as an anesthetic spread rapidly, it was not universally accepted at the time of Sims' experimental surgery.[6]

In addition, a common belief at the time was that black people did not feel as much pain as white people.[22] One patient, named Lucy, nearly died from sepsis. He had operated on her without anesthetics in the presence of twelve doctors, following the experimental use of a sponge to wipe urine from the bladder during the procedure.[17] She contracted sepsis because he left this sponge in her urethra and bladder.[20] He did administer opium to the women after their surgery, which was accepted therapeutic practice of the day.[23]

After the extensive experimental surgery, and complications, Sims finally perfected his technique. He repaired the fistulas successfully in Anarcha. The silver-wire sutures, developed in 1849,[7]:10 helped him make the first completely successful repair of a fistula. Sims published an account of this in his surgical reports of 1852.[3] He proceeded to repair fistulas in several other enslaved women.[24] According to Durrenda Ojanuga from the University of Alabama, "Many white women came to Sims for treatment of vesicovaginal fistula after the successful operation on Anarcha. However, none of them, due to the pain, were able to endure a single operation." The Journal of Medical Ethics reports a case study of one white woman, whose fistula was repaired by Sims without the use of anesthesia, in a series of three operations carried out in 1849.[6]

Sims later moved to New York to found a Woman's Hospital, where he performed the operation on white women. According to Ojanuga, Sims used anesthesia when conducting fistula repair on white women. But L. L. Wall, also writing for the Journal of Medical Ethics, states that as of 1857, Sims did not use anesthesia to perform fistula surgery on white women, citing a public lecture where Sims spoke to the New York Academy of Medicine on November 18, 1857. During this lecture, Sims said that he never used anesthesia for fistula surgery "because they are not painful enough to justify the trouble and risk attending their administration". While acknowledging this as shocking to modern sensibilities, Wall noted that Sims was expressing the contemporary sensibilities of the mid-1800s, particularly among surgeons who began their practice in the pre-anesthetic era.[17][22][6] In 1874 Sims addressed the New York State Medical Society on "The Discovery of Anaesthesia",[25][26] and in 1880 read to the New York Academy of Medicine a paper, soon published, about a death from anesthesia.[7]:22[27]

Trismus nascentium

During his early medical years, Sims also became interested in "trismus nascentium", also known as neonatal tetanus, that occurs in newborns. A 19th century doctor described it as "a disease that has been almost constantly fatal, commonly in the course of a few days; the women are so persuaded of its inevitable fatality that they seldom or ever call for the assistance of our art."[28]

Trismus nascentium is a form of generalised tetanus. Infants who have not acquired passive immunity from the mother having been immunised are at risk for this disease. It usually occurs through infection of the unhealed umbilical stump, particularly when the stump is cut with a non-sterile instrument. In the 21st century, neonatal tetanus mostly occurs in developing countries, particularly those with the least developed health infrastructure. It is rare in developed countries.[29]

Trismus nascentium is now recognized to be the result of unsanitary practices and nutritional deficiencies. In the 19th century its cause was unknown, and many enslaved African children contracted this disease. Medical historians believe that the conditions of the quarters of enslaved people were the cause. Sims alluded to the idea that sanitation and living conditions played a role in contraction.[12]

He wrote:

Whenever there are poverty, and filth, and laziness, or where the intellectual capacity is cramped, the moral and social feelings blunted, there it will be oftener found. Wealth, a cultivated intellect, a refined mind, an affectionate heart, are comparatively exempt from the ravages of this unmercifully fatal malady. But expose this class to the same physical causes, and they become equal sufferers with the first.[12]

Sims also thought trismus nascentium developed from skull bone movement during protracted births. To test this, Sims used a shoemaker's awl to pry the skull bones of enslaved infants into alignment. These experiments had a 100% fatality rate. Sims often performed autopsies on the corpses, which he kept for further research on the condition.[12][30]He blamed these fatalities on "the sloth and ignorance of their mothers and the black midwives who attended them", as opposed to the extensive experimental surgeries that he conducted upon the babies.[30][31][32]

Critiques of experimentation

Sims' experimental surgeries without anesthesia on enslaved women, who could not consent, have been described since the late 20th century as an example of racism in the medical profession. This is seen as part of the historical oppression of blacks and vulnerable populations in the United States.[3] Patients of Sims' fistula and trismus nascentium operations were not given available anesthetics. He caused the deaths of babies on whom he operated for the trismus nascentium condition.

In regards to Sims' discoveries, Durrenda Ojenunga wrote in 1993:

His fame and fortune were a result of unethical experimentation with powerless Black women. Dr Sims, 'the father of gynaecology', was the first doctor to perfect a successful technique for the cure of vesico-vaginal fistula, yet despite his accolades, in his quest for fame and recognition, he manipulated the social institution of slavery to perform human experimentation, which by any standard is unacceptable.[17]

Terri Kapsalis writes in Mastering the Female Pelvis, "Sims' fame and wealth are as indebted to slavery and racism as they are to innovation, insight, and persistence, and he has left behind a frightening legacy of medical attitudes toward and treatments of women, particularly women of color."[33]

Drawing on Sims's published autobiography, case-histories, and correspondence, historian Stephen C. Kenny highlights how Sims's surgical treatment of enslaved infants suffering from neonatal tetanus was a typical, but tragically distinctive, feature in the career of an ambitious medical professional in the slave South. Individual doctors like Sims and the profession were incentivized in multiple ways through the system of chattel slavery, many were not only enslaver-physicians, but also traded in enslaved people, while at the same time their medical research was advanced directly and significantly through the exploitation of the enslaved population.[30] In a related article exploring the types, frequency and functions of slave hospitals in the American South, Kenny identifies Sims's private 'negro infirmary' located behind his office on South Perry as an example of a 'hospital-for-experimentation', where Sims also undertook a series of gruelling and dangerous invasive surgeries on enslaved men. Sims used the surgical opportunities presented by long neglected chronic - and often incurable - cases of illness and injuries among the enslaved to sharpen his skills and stake a claim for professional celebrity - all in the context of the profits to be made from human trafficking one of the South's busiest slave markets.[34]

Author Harriet A. Washington, in her 2007 book Medical Apartheid, writes of Sims' experiments: "Each naked, unanesthetized slave woman had to be forcibly restrained by other physicians through her shrieks of agony as Sims determinedly sliced, then sutured her genitalia."[35] Facing South, a publication of the Institute for Southern Studies, wrote that slaves were forced to hold each other down during surgery.[36]

Physician L. L. Wall, writing in the Journal of Medical Ethics, says fistula surgery on non-anesthetized patients would require cooperation from the patient, and would not be possible if there were any active resistance from the patient. Wall writes that surviving documentation from the time says the women were trained to assist in their own surgical procedures. Wall also argues the documentation suggests the women consented to the surgeries, as the women were motivated to have their fistulas repaired, due to the serious medical and social nature of vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas.[6] According to gynaecologist Caroline M. de Costa, writing in the Medical Journal of Australia:

Hideous as the accounts of his surgery may appear to sensitive 20th century eyes, undoubtedly Sims was at least partly motivated by a desire to improve the lot of his enslaved patients. In this, he was no different from many 19th century surgeons experimenting with the techniques that are the foundation of current surgical practice, gynaecological and otherwise. The lives of the slave women on whom Sims experimented would have been even more miserable without their subsequent cures, and the knowledge gained has been applied to fistula repair for thousands of women since.[37]

In his autobiography, J. Marion Sims said he was indebted to the enslaved women on whom he experimented. After multiple failed operations he was discouraged, and the enslaved women encouraged him to proceed, because they were determined to have their medical afflictions cured.[6] Shortly after Sims' successful repair of Anarcha's vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in 1849, he successfully repaired the fistulas of the other enslaved women. They returned to their owners' plantations.[24]

Sims has been criticized for operating on the enslaved women without their consent. Wall writes in the Journal of Medical Ethics that legally, consent was granted by the slaves' owners. He noted that enslaved women were a "vulnerable population" with respect to medical experimentation. Wall also writes that Sims obtained consent from the women themselves.

He cites an 1855 passage from New York Medical Gazette and Journal of Health, where Sims wrote:

For this purpose [therapeutic surgical experimentation] I was fortunate in having three young healthy colored girls given to me by their owners in Alabama, I agreeing to perform no operation without the full consent of the patients, and never to perform any that would, in my judgment, jeopard life, or produce greater mischief on the injured organs—the owners agreeing to let me keep them (at my own expense) till I was thoroughly convinced whether the affection could be cured or not.[6]

Deirdre Cooper Owens wrote: "Sims has been painted as either a monstrous butcher or a benign figure who, despite his slaveowning status, wanted to cure all women from their distinctly gendered suffering."[38] She describes these opposing views as overly reductionist, saying his history is more nuanced. He lived in a slave-holding society and expressed the racism and sexism that were considered normal during his time. He contributed significantly to the field of gynecological surgery. Sims' suture technique developed in the 1840s for fistula surgery is still in use by modern-day physicians.[38]

New York and Europe

Sims moved to New York in 1853 because of his health and was determined to focus on diseases of women. He had an office at 267 Madison Avenue.[39]

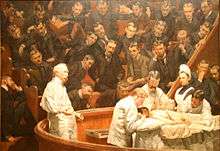

In 1855 he founded the Woman's Hospital, the first hospital for women in the United States. His project met with "universal opposition" from the New York medical community;[7]:11 it was due to prominent women that he established it. They were visited by "prominent doctors, who endeavored to convince them that they were making a mistake, that they had been deceived, that no such hospital was needed, etc."[7]:12–13 "I was called a quack and a humbug, and the hospital was pronounced a fraud. Still it went on with its work."[7]:13 In the Woman's Hospital, he performed operations on indigent women, often in an operating theatre so that medical students and other doctors could view it, as was considered fundamental to medical education at the time.[15] Patients remained in the hospital indefinitely and underwent repeated procedures.[15]

Sims and the Confederacy

In 1861, during the American Civil War, Sims, a "loyal Southerner",[15]:46 moved to Europe, where he toured hospitals and worked on fistula patients in London, Paris, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Brussels.[12][7] However, according to J.C. Hallman, he was there as one of several government agents of the Confederacy, who were seeking money (loans), diplomatic recognition of their new government (no country ever recognized it), and supplies and ships. An intercepted letter informed Lincoln's Secretary of State, William H. Seward, that Sims was "secessionist in sentiment", and that his "purpose in going abroad at this time is believed to be hostile to the government", as Seward reported to U.S. diplomats in Europe.[40] According to the U.S. Minister in Brussels Henry Shelton Sanford, Sims was a "violent secessionist", and his "movements in Europe had 'given color to (the) opinion' that he was a spy".[40]

The most celebrated episode in Sims' life was his summons, in 1863, to treat Empress Eugénie for a fistula. This widely reported episode helped Sims to solidify his worldwide reputation as a surgeon.[12] But according to Hallman, no source confirms that Eugénie had any medical problem at all. Simms' visits to the palace were semi-diplomatic Confederate visits, and the illness an invention to escape the vigilance of the U.S. diplomats, who had their eyes on Sims. Eugénie became an "ardent disciple" of the Confederacy.[40]

Expressing the views of many Southern whites, Sims later said that it was a "dreadful mistake ... to give the negro the franchise."[40] Two years later, offering a toast on board the steamer Atlantic, returning to Europe, he claimed that in the aftermath of the war, the South had been degraded “beyond the level of the meanest slave that ever wore a shackle.”[40]

At the same time, Sims argued that it was puerile for the South to sulk in its loss. He called for an acceptance of the issues of the war, including the Fifteenth Amendment. "It is folly to talk of the lost cause," he said.[40]

Later career

Having treated royalty, after his return to the United States, Sims raised his charges in his private practice. He effectively limited it to wealthy women, although "he always had a long roll of charity patients".[41]:25 He became known for the Battey surgery, which contributed to his "honorable reputation". This involved the removal of both ovaries. It became a popular treatment to relieve insanity, epilepsy, hysteria, and other "disorders of the nerves" (as mental illness was called at the time). At the time, these were believed to be caused by disorders of the female reproductive system.[15]

Sims received honors and medals for his successful operations in many countries. Since the 20th century, the necessity of many of these surgeries has been questioned. He performed surgery for what were considered gynecological issues: such as clitoridectomies, then believed to control hysteria or improper behavior related to sexuality. These were done at the requests of the women's husbands or fathers, who were permitted under the law to commit the women to surgery involuntarily.[24]

Under the patronage of Napoleon III, Sims organized the American-Anglo Ambulance Corps, which treated wounded soldiers from both sides at the Battle of Sedan.[24]

Break with the Woman's Hospital

In 1871, Sims returned to New York. He got into a conflict with the other doctors of the Woman's Hospital, with whom he carried on a dialogue by means of published pamphlets.[42][43][44] One issue was whether the hospital would treat women with uterine cancer, because the hospital was founded to treat diseases of women, and cancer was not a disease peculiar to women. In addition, cancer was feared as contagious. The second issue was how many outsiders (doctors or medical students) could observe any given operation, as was common at the time. This meant they could observe the sexual organs of white women patients; there were no African-American patients. The Board of the hospital set a limit of 15; previously there had been as many as 60.

After quarreling with the board of the Woman's Hospital over the admission of cancer patients, Sims became instrumental in establishing America's first cancer institute, New York Cancer Hospital.[45] Hallman says that "Sims was thrown out of his own hospital in New York in 1874, in part because his fellow doctors had determined that his work was reckless and lethal".[40]

In reply to the treatment he received from the Woman's Hospital, Sims was unanimously elected president of the American Medical Association, an office he held from 1876 to 1877.[10]:18[12]

Death

Sims suffered two angina attacks in 1877, and in 1880, contracted a severe case of typhoid fever. W. Gill Wylie, an early 20th-century biographer, said that although Sims suffered delirium, he was "constantly contriving instruments and conducting operations".[7] After several months and a move to Charleston to aid his convalescence, Sims recovered in June 1881. He traveled to France. After his return to the United States in September 1881, he began to complain of an increase in heart problems.

According to Wylie, Sims consulted with doctors for his unknown cardiac condition both in the United States and in Europe. He was "positive that he had a serious disease of the heart and it caused deep mental depression".[7] He was halfway through writing his autobiography and planning a return visit to Europe when he died of a heart attack on November 13, 1883 in Manhattan, New York City. He had just visited a patient with his son, H. Marion Sims. He is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Legacy and honors

- On the title page of the reprint of an article, "History of the Discovery of Anesthesia", first published in the May 1877 number of the Virginia Medical Monthly, Sims listed his honors as:

Author of "Silver Sutures in Surgery," "The Sims Operation for Vesico-Vaginal Fistula," "Uterine Diseases," "History of the Discovery of Anaesthesia", Etc., Etc.; Member of the Historical Society of New York; Surgeon to the Empress Eugenie; Delegate to Annual Conference of the Association for the Reform and Codification of the Law of Nations, 1879; Founder of the Woman's Hospital of the State of New York, and formerly Surgeon to the Same; Centennial President of the American Medical Association, Philadelphia, 1876; President of the International Medical Congress at Berne, 1877; Fellow of the American Medical Association; Permanent Member of the New York State Medical Society; Fellow of the Academy of Sciences, of the Academy of Medicine, of the Pathological Society, of the Neurological Society, of the County Medical Society, and of the Obstetrical Society of New York; Fellow of the American Gynaecological Association; Honorary Fellow of the State Medical Societies of Connecticut, Virginia, South Carolina, Alabama and Texas; Honorary Fellow of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Brussels; Honorary Fellow of the Obstetrical Societies of London, Dublin and Berlin, and of the Medical Society of Christiana [Oslo]; Knight of the Legion of Honor (France); Commander of Orders of Belgium, Germany, Austria, Russia, Spain, Portugal and Italy, Etc., Etc., Etc.[39]

- A bronze statue by Ferdinand Freiherr von Miller (the younger), depicting Sims in surgical wear,[46] was erected in Bryant Park, New York, in 1894, taken down in the 1920s amid subway construction, and moved to the northeastern corner of Central Park, at 103rd Street, in 1934, opposite the New York Academy of Medicine.[24][47] The address delivered at its rededication was published in the Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine.[48] This is the first statue erected in the United States in honor of any physician. The statue became the center of protests in 2017 due to Sims' operations on enslaved black women.[49] The statue was defaced with the word RACIST and painted the eyes red.[50] In April 2018, the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to have the statue removed from Central Park and installed in Green-Wood Cemetery, near where Sims is buried.[47]

- Another memorial was installed on the grounds of his alma mater, Jefferson Medical College.

- There is a statue on the grounds of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery[3] (dedicated in 1939[51]). In April 2018, when Silent Sam was doused with red ink and blood, the statue had ketchup thrown on it while a skit about Sims was performed.[52] "An alternative statue of Sims's 'first cure', the young woman known as Anarcha, was erected in protest only to be stolen in the night."[51]

- Another statue of Sims, installed in 1929,[53] is at the South Carolina State House in Columbia; the mayor of Columbia, Stephen K. Benjamin, in 2017 called for its removal,[54] as have other protestors.[55]

- A painting by Marshall Bouldin III entitled Medical Giants of Alabama, that depicted Sims and other white men standing over a partially clothed black patient, was commissioned for $20,000 in 1982 (paid for by donors). It was on display at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Center for Advanced Medical Studies, but was removed in late 2005 or early 2006 because of complaints from people offended by it, and the ethical questions associated with Sims.[56][57]

- The Medical University of South Carolina, whose predecessor Sims attended, set up around 1980 an endowed chair in his honor. In February, 2018, the chair was quietly renamed.[58] However, a "J. Marion Sims Chair" in obstetrics and gynecology still appears in a March 2018, program.[59] A J. Marion Sims Society, a student organization, existed there from 1923 to 1945.[60]

- A Sims Memorial Address on Gynecology, delivered before the South Carolina Medical Society at Charleston, is documented from 1927.[61]

- In 1950, a historical marker was erected near the site of his parents' farmhouse, where he was born. Present at the dedication ceremony were Congressman James P. Richards and representatives of the American Medical Association, the Medical College of South Carolina, the University of South Carolina, the chairman of Lancaster's Marion Sims Memorial Hospital board, the state archivist of South Carolina, and four of Sims' children. Dr. Roderick McDonald, president of the South Carolina Medical Association, introduced the speaker, Dr. Seale Harris, past president of the Southern Medical Association and former editor of the Southern Medical Journal, whose biography of Sims, Woman's Surgeon: the Life Story of J. Marion Sims, had just been published.[62][3]

- A cartoon of Sims appeared on the cover of the November, 2017, issue of The Nation.

- A J. Marion Sims Foundation was founded in 1995 in his home town of Lancaster, South Carolina. It has dispensed almost $50,000,000 in grants.[63]

- The Marion Sims Memorial Hospital is located in Lancaster.

- In Montgomery, Alabama, a historical marker at 37 South Perry St. marks the location of Sims' house and backyard hospital or infirmary. The building on the site is from the early 20th century.[64]

- In 1953, Sims was elected to the Alabama Hall of Fame.[16]

Contributions

- Vaginal surgery: fistula repair. Invented silver wire as a suture.

- Instrumentation: Sims' speculum; Sims' sigmoid catheter.

- Exam and surgical positioning: Sims' position.

- Fertility treatment: Insemination and postcoital test.

- Cancer care: Sims argued for the admission of cancer patients to the Woman's Hospital, despite contemporary beliefs that the disease was contagious.

- Abdominal surgery: Sims advocated a laparotomy to stop bleeding from bullet wounds to this area, repair the damage and drain the wound. His opinion was sought when President James Garfield was shot in an assassination attempt; Sims responded from Paris by telegram. Sims' recommendations later gained acceptance.[24]

- Gallbladder surgery: In 1878, Sims drained a distended gallbladder and removed its stones. He published the case believing it was the first of its kind; however, a similar case had already been reported in Indianapolis in 1867.[24]

See also

References

- Sims 1889, p. 32.

- Sims 1889, p. 23.

- Spettel, Sarah; White, Mark Donald (June 2011). "The Portrayal of J. Marion Sims' Controversial Surgical Legacy" (PDF). The Journal of Urology. 185 (6): 2424–2427. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.077. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

-

- Lerner, Barron (October 28, 2003). "Scholars Argue Over Legacy of Surgeon Who Was Lionized, Then Vilified". The New York Times.

- Wall, L. L. (June 2006). "The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record". Journal of Medical Ethics. 32 (6): 346–350. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.012559. ISSN 0306-6800. PMC 2563360. PMID 16731734.

- Wylie, W. Gill (1884). Memorial Sketch of the Life of J. Marion Sims. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Ward, George Gray (March 1936), "Marion Sims and the Origin of Modern Gynecology", Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 12 (3): 93–104, PMC 1965916, PMID 19311983

- Sims, J. Marion (1885), The Story of My Life, D. Appleton & Company, retrieved October 20, 2018

- Baldwin, W. O. (1884). Tribute to the late James Marion Sims. Montgomery, Alabama: Montgomery, Ala.

- "South Carolina Female Collegiate Institute, Barhamville — History of South Carolina Slide Collection". South Carolina ETV Commission. 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- Brinker, Wendy (2000). "J. Marion Sims: One Among Many Monumental Mistakes". A Dr. J. Marion Sims Dossier. University of Illinois. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- Chalakoski, Martin (May 9, 2018). "J. Marion Sims, the controversial 'father of modern gynecology,' conducted experiments on enslaved women and did not use anesthesia". The Vintage News. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Curry, Richard O.; Cowden, Joanna Dunlop (1972). Slavery in America: Theodore Weld's American Slavery As It Is. Itasca, Illinois: F. E. Peacock. OCLC 699102217.

- Kapsalis, Terri (January 25, 1997). Public Privates: Performing Gynecology from Both Ends of the Speculum. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822319214 – via Google Books.

- "James Marion Sims". Alabama Department of Archives and History. 1995. Archived from the original on January 28, 1999. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- Ojunga, Durrenda (March 1993). "The medical ethics of the 'Father of Gynaecology', Dr J Marion Sims". Journal of Medical Ethics. 19 (1): 28–31. doi:10.1136/jme.19.1.28. PMC 1376165. PMID 8459435.

- Axelson, Diana E. (1985). "Women as Victims of Medical Experimentation: J. Marion Sims' Surgery on Slave Women, 1845–1850". Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women. 2 (2): 10–13. PMID 11645827.

- McGinnis, Lamar S., Jr. (January 1, 2017). "J. Marion Sims: Paving the way". Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Kapsalis, Terri (2002). "Mastering the Female Pelvis: Race and the Tools of Reproduction". In Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (ed.). Skin Deep, Spirit Strong: The Black Female Body in American Culture (PDF). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. pp. 263–300. ISBN 978-0472067077.

- Snorton, C. Riley (October 25, 2017). Black on Both Sides. University of Minnesota Press. doi:10.5749/minnesota/9781517901721.001.0001. ISBN 9781517901721.

- Vedantam, Shankar; Gamble, Vanessa Northington (February 16, 2016). "Remembering Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey: The Mothers of Modern Gynecology". NPR. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Wall, L. Lewis (July 2007). "Did J. Marion Sims deliberately addict his first fistula patients to opium?". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 62 (3): 336–356. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrl045. PMID 17082217.

- Shingleton, H. M. (March–April 2009). "The Lesser Known Dr. Sims". ACOG Clinical Review. 14 (2): 13–16.

- Sims, J. Marion (May 1877). "The Discovery of Anaesthesia". Virginia Medical Monthly.

- Rosenbloom, Julia M.; Schonberger, Robert B. (2015). "The outlook of physician histories: J. Marion Sims and 'The Discovery of Anaesthesia'". Medical Humanities. 41 (2): 102–106. doi:10.1136/medhum-2015-010680. PMID 26048369.

- Sims, J. Marion (1880). The bromide of ethyl as an anaesthetic. New York Academy of Medicine.

- Hartigan, J.F. (1884). The Lock-Jaw of Infants. Bermingham & Co. p. 17.

- Roper, Martha (September 12, 2007). "Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- Kenny, Stephen C. (August 1, 2007). "'I can do the child no good': Dr Sims and the Enslaved Infants of Montgomery, Alabama". Social History of Medicine. 20 (2): 223–241. doi:10.1093/shm/hkm036. ISSN 1477-4666.

- Washington, Harriet A. (2008). Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 62–63.

- Perper, Joshua A.; Cina, Stephen J. (2010). When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 88.

- Kapsalis, Terri (March 24, 2019). "Mastering the Female Pelvis". Ann Arbor: 263. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kenny, S. C. (January 1, 2010). ""A Dictate of Both Interest and Mercy"? Slave Hospitals in the Antebellum South". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 65 (1): 1–47. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrp019. ISSN 0022-5045.

- Trouillot, Terence (August 23, 2017). "Pressure Builds to Take Down a Particularly Gruesome NYC Monument to Doctor Who Experimented on Female Slaves". ArtNet. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Barber, Rebekah (August 25, 2017). "Monuments to the father of gynecology honor brutality against Black women". Facing South. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- de Costa, Caroline M. (June 2003). "James Marion Sims: some speculations and a new position" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia. 178 (12): 660–663. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05401.x. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- Owens, Deidre Cooper (August 2, 2017). "More Than a Statue: Rethinking J. Marion Sims' Legacy". Rewire.News. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Sims, J. Marion (May 1877). "History of the discovery of anaesthesia". Virginia Medical Monthly: 1.

- Hallman, J.C. (September 28, 2018). "J. Marion Sims and the Civil War — a rollicking tale of deceit and spycraft". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Sims, J. Marion (1877). "Introduction". In Marion-Sims, H. (ed.). The Story of My Life. D. Appleton & Company.

- Peaslee, E R; Emmet, Thomas Addis; Thomas, T Gaillard (1877). To the medical profession: statements respecting the separation of Dr. J. Marion Sims from the Woman's Hospital, New York. New York.

- Sims, J. Marion (1877). The Woman's Hospital in 1874. A Reply to the Printed Circular of Drs. E. R. Peaslee, T. A. Emmet, and T. Gailliard Thomas. New York: New York : Kent, printers.

- Peaslee, E. R.; Emmet, T. A.; Thomas, T. G. (1877). Reply to Dr. J. Marion Sims' Pamphlet, entitled 'The Woman's Hospital in 1874'. New York: Trow's Printing and Bookbinding.

- "J. Marion Sims". Innovative Healthcare: MUSC's Legacy of Progress. Waring Historical Library. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- The bronze standing figure is signed "[F. v]on Miller fec. München 1892" (Text of historical sign).

- Neuman, William (April 16, 2018). "City Orders Sims Statue Removed from Central Park". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Ward, George Gray (December 1934). "Marion Sims and the origin of modern gynecology". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. Second. 10 (12): 721–724.

- Pérez, Miriam Zoila. "New Target for Statue Removal: 'Father of Gynecology' Who Operated on Enslaved Black Women". Race Forward. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Krause, Kenneth (2018). "Science (Indeed, the World?) Needs Fewer, Not More, Icons". Skeptical Inquirer. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. 42 (1): 23–25.

- Hallman, J.C. (September 28, 2018). "J. Marion Sims and the Civil War — a rollicking tale of deceit and spycraft". Montgomery Advertiser. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Charges dropped against man accused of throwing ketchup on Confederate statue at Capitol". Montgomery Advertiser. Associated Press. October 9, 2018.

- James Marion Sims memorial : unveiled May 10, 1929, Columbia, South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina, 1929, retrieved October 27, 2018

- Roldán, Cynthia (August 16, 2017). "Steve Benjamin says monument at SC State House 'should come down at some point'". The State. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- Marchant, Bristow (August 25, 2017). "Protesters want Confederate monuments removed from SC State House". The State. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- Brown, Deneen L. (August 30, 2017). "A surgeon from SC experimented on slave women without anesthesia. Now his statues are under attack". The State. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- "A 19th-Century Doctor & [sic]". The Washington Post. January 29, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- Zhang, Sarah (April 18, 2018). "The Surgeon Who Experimented on Slaves". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Medical University of South Carolina (March 24–26, 2018). "49th Annual Updates and Challenges in Obstetrics & Gynecology Spring Symposium". Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Medical University of South Carolina (2007), J. Marion Sims Medical Society Records (PDF), retrieved October 25, 2018,

Finding aid.

- The Sims memorial address on gynecology, delivered before the South Carolina Medical Society at Charleston, November 22, 1927, OCLC 18214591

- Pettus, Louise (2000). "Dr. J. Marion Sims". South Carolina GenWeb project. Archived from the original on July 8, 2001. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- J. Marion Sims Foundation. "History". Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- Hattabaugh, Lee (2010). "Office of Dr. Luther Leonidas Hill Office Site of Dr. J. Marion Sims". Historical Markers Database.

Further reading

- Sims, James Marion (1866). Clinical notes on uterine surgery: With Special Reference to the Management of the Sterile Condition. London: Robert Hardwicke. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- Sims, James Marion (1889). The Story of My Life. New York: Appleton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Seale; Browin, Frances Williams (1950). Woman's surgeon : the life story of J. Marion Sims. New York.

- Speert, H. (1958). Obstetrics and Gynecologic Milestones. New York: MacMillan. pp. 442–454.

- McGregor, Deborah Kuhn (1990). Sexual surgery and the origins of gynecology : J. Marion Sims, his hospital, and his patients. Garland. ISBN 978-0824037680.

- Ojanuga, D. (1993). "The medical ethics of the 'father of gynaecology', Dr J Marion Sims". Journal of Medical Ethics: 1928–1931.

- Gamble, Vanessa (November 1997). "Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care". American Journal of Public Health: 1773.

- Kapsalis, Terri (2002). "Mastering the Female Pelvis: Race and the Tools of Reproduction". In Wallace-Sanders, Kimberly (ed.). Skin Deep, Spirit Strong: The Black Female Body in American Culture. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. pp. 263–300. ISBN 978-0472067077.

- Kenny, Stephen C., “A Dictate of Both Interest and Mercy”? Slave Hospitals in the Antebellum South, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Volume 65, Issue 1, January 2010, Pages 1–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrp019

- Owens, Deirdre Cooper (2017). Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology.

- Schwartz, Marie Jenkins (2006). Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the American South.

- Spencer, Thomas (January 21, 2006). "UAB shelves divisive portrait of medical titans: Gynecologist's practices at heart of debate". Birmingham News.

- Washington, Harriet A. (2008). Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Anchor. ISBN 978-0385509930.

- Spettel, S.; White, M.D. (June 2011). "The Portrayal of J. Marion Sims' Controversial Surgical Legacy". The Journal of Urology. 185 (6): 2424–2427. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.077. PMID 21511295.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. Marion Sims. |

- "J. Marion Sims", Encyclopedia of Alabama

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- J. Marion Sims Letters, South Carolina Digital Library

- J. Marion Sims at Find a Grave