J'Accuse…!

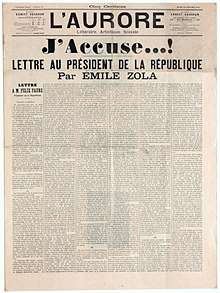

"J'Accuse...!" (French pronunciation: [ʒakyz]; "I Accuse...!") was an open letter published on 13 January 1898 in the newspaper L'Aurore by the influential writer Émile Zola. In the letter, Zola addressed President of France Félix Faure and accused the government of anti-Semitism and the unlawful jailing of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Army General Staff officer who was sentenced to lifelong penal servitude for espionage. Zola pointed out judicial errors and lack of serious evidence. The letter was printed on the front page of the newspaper and caused a stir in France and abroad. Zola was prosecuted for libel and found guilty on 23 February 1898. To avoid imprisonment, he fled to England, returning home in June 1899.

| Part of a series on the |

| Dreyfus affair |

|---|

Military degradation of Alfred Dreyfus |

| People |

Other pamphlets proclaiming Dreyfus's innocence include Bernard Lazare's A Miscarriage of Justice: The Truth about the Dreyfus Affair (November 1896). As a result of the popularity of the letter, even in the English-speaking world, J'accuse! has become a common generic expression of outrage and accusation against someone powerful.[1][2]

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus was born in 1859 in the city of Mulhouse, which was then located in the province of Alsace in northeast France. Born into a prosperous Jewish family,[3] he left his native town for Paris in 1871 in response to the annexation of the province by Germany following the Franco-Prussian War. In 1894, while an artillery captain for the General Staff of France, Dreyfus was suspected of providing secret military information to the German government.[3]

A cleaning woman and French spy by the name of Madame Marie Bastian working at the German Embassy was at the source of the investigation. She routinely searched wastebaskets and mailboxes at the German Embassy for suspicious documents.[4] She found a suspicious bordereau (detailed listing of documents) at the German Embassy in 1894, and delivered it to Commandant Hubert-Joseph Henry, who worked for French military counterintelligence in the General Staff.[4]

The bordereau had been torn into six pieces, and had been found by Madame Bastian in the wastepaper basket of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attaché.[4] When the document was investigated, Dreyfus was convicted largely on the basis of testimony by professional handwriting experts:[5] the graphologists asserted that "the lack of resemblance between Dreyfus' writing and that of the bordereau was proof of a 'self-forgery,' and prepared a fantastically detailed diagram to demonstrate that this was so."[6] There were also assertions from military officers who provided confidential evidence.[5]

Dreyfus was found guilty of treason in a secret military court-martial, during which he was denied the right to examine the evidence against him. The Army stripped him of his rank in a humiliating ceremony and shipped him off to Devil's Island, a penal colony located off the coast of French Guiana in South America.[4]

At this time, France was experiencing a period of anti-Semitism, and there were very few outside his family who defended Dreyfus. Nevertheless, the initial conviction was annulled by the Supreme Court after a thorough investigation. In 1899, Dreyfus returned to France for a retrial, but although found guilty again, he was pardoned.[4] In 1906, Dreyfus appealed his case again, and obtained the annulment of his guilty verdict. In 1906, he was also awarded the Cross of the Légion d'honneur, which was for “a soldier who has endured an unparallelled martyrdom".[5]

History of Émile Zola

Émile Zola was born on 2 April 1840 in Paris.[7] Zola's main literary work was Les Rougon-Macquart, a monumental cycle of twenty novels about Parisian society during the French Second Empire under Napoleon III and after the Franco-Prussian War.[7] He was also the founder of the Naturalist movement in 19th-century literature.[7] Zola was among the strongest proponents of the Third Republic and was elected to the Légion d'honneur.[7] He risked his career in January 1898 when he decided to stand up for Alfred Dreyfus. Zola wrote an open letter to the President of France, Félix Faure, accusing the French government of falsely convicting Alfred Dreyfus and of anti-Semitism.[7] His intention was to draw the accusation so broadly that he would essentially force men in the government to sue him for libel. Once the suit was filed, the Dreyfusards (supporters of Dreyfus) would have the opportunity to acquire and publicize the shaky evidence on which Dreyfus had been convicted. Zola titled his letter "J’Accuse" (French for "I Accuse"), which was published on the front page of Georges Clemenceau's liberal Paris daily L'Aurore.[7] Zola was brought to trial for libel for publishing his letter to the President, and was convicted two weeks later. He was sentenced to jail and was removed from the Légion d'honneur.[7] To avoid jail time, Zola fled to England, and stayed there until the French Government collapsed; he continued to defend Dreyfus.[7] Four years after this famous letter to the president, Zola died from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a blocked chimney. On 4 June 1908, Zola's remains were laid to rest in the Panthéon in Paris.[7]

In 1953, the newspaper Liberation published a death-bed confession by a Parisian roofer that he had murdered Zola by blocking the chimney of his house.[8]

Arguments in J'Accuse

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Émile Zola argued that "the conviction of Alfred Dreyfus was based on false accusations of espionage and was a misrepresentation of justice."[7] He first points out that the real man behind all of this is Major du Paty de Clam. Zola states: "He was the one who came up with the scheme of dictating the text of the bordereau to Dreyfus; he was the one who had the idea of observing him in a mirror-lined room. And he was the one whom Major Forzinetti caught carrying a shuttered lantern that he planned to throw open on the accused man while he slept, hoping that, jolted awake by the sudden flash of light, Dreyfus would blurt out his guilt."[9]

Next, Zola points out that if the investigation of the traitor was to be done properly, the evidence would clearly show that the bordereau came from an infantry officer, not an artillery officer such as Dreyfus.[9]

Zola argues Dreyfus's innocence can be readily inferred from the circumstances when he states: "These, Sir, are the facts that explain how this miscarriage of justice came about; The evidence of Dreyfus's character, his affluence, the lack of motive and his continued affirmation of innocence combine to show that he is the victim of the lurid imagination of Major du Paty de Clam, the religious circles surrounding him, and the 'dirty Jew' obsession that is the scourge of our time."[9]

After more investigation, Zola points out that a man by the name of Major Esterhazy was the man who should have been convicted of this crime, and there was proof provided, but he could not be known as guilty unless the entire General Staff was guilty, so the War Office covered up for Esterhazy.

At the end of his letter, Zola accuses General Billot of having held in his hands absolute proof of Dreyfus's innocence and covering it up.[9] He accuses both General de Boisdeffre and General Gonse of religious prejudice against Alfred Dreyfus.[9] He accuses the three handwriting experts, Messrs. Belhomme, Varinard and Couard, of submitting false reports that were deceitful, unless a medical examination finds them to be suffering from a condition that impairs their eyesight and judgment.[9]

Zola's final accusations were to the first court martial for violating the law by convicting Alfred Dreyfus on the basis of a document that was kept secret, and to the second court martial for committing the judicial crime of knowingly acquitting Major Esterhazy.[9]

Léon Bloy has expressed, in Je M'Accuse...,[10] as to be expected, a different, probably unpopular, and not so very flattering opinion of Zola's motives for getting involved in the Dreyfus Affair and for writing his open letter J'Accuse. Ever the staunch critic of the man and his work, Bloy wrote a scathing attack about it in his Je M'Accuse... (1900)[10].

Subsequent use of the term

_March_25th_1925_editorial_addressed_to_Lord_Balfour.pdf.jpg)

- In 1915, the German pacifist Richard Grelling wrote a book titled J'Accuse! in which he condemned the actions of the German Empire.

- In 1919, Abel Gance released his film J'accuse as a statement against World War I, shooting Gance to international fame.

- In 1925, the most popular Palestinian Arab newspaper, Filastin (La Palestine), published a four-page editorial protesting the Balfour Declaration with the title "J'Accuse!"

- In 1938, the Belgian fascist politician Léon Degrelle published a polemic booklet titled J'accuse against minister Paul Stengers, of being a "cumulard, a bankster, a plunderer of savings and a coward". It provoked a retaliatory pamphlet titled J'accuse Léon Degrelle.

- In 1950, on Easter Sunday, members of the Lettrist movement proclaimed the death of God before the congregation of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. Michel Mourre used the phrase "J'accuse" to proclaim what he saw as the wickedness of the Roman Catholic Church.

- In 1954, during the controversy surrounding J. Robert Oppenheimer and the allegations that he posed a security risk to the Atomic Energy Commission, journalists Joseph and Stewart Alsop wrote an article for Harper's Magazine titled "We Accuse!", in which they defend Oppenheimer as the victim of a petty grudge held by AEC chairman Lewis Strauss.[11]

- In 1961, during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, head prosecutor Gideon Hausner used the phrase in his opening statement.[12]

- In 1974 the book 'Upon My Word!' contained a humorous story from the UK radio panel game 'My Word' by Frank Muir which featured Zola calling for an imaginary English painter named Jack Hughes to assist Manet in painting 'Dejeuner sur l'herbe'.

- In 1982, Commentary Magazine editor Norman Podhoretz used the title "J'Accuse" for an article blaming anti-semitism for allegedly excessive criticism of Israel during the 1982 Israel-Lebanon war.[13]

- In 1997, the South Park episode "Terrance and Phillip in Not Without My Anus" sees Terrance and Phillip on trial for murder. During the closing argument, Scott, the prosecutor says "j'ai accuse" (sic).

- In 1998, the Australian satirical television program The Games debuted a character named Jack Hughes in an episode titled "J'Accuse". The show was a satire critical of, among other things, corruption in the organizing of the Olympic Games in Sydney; the character Jack Hughes was a journalist who often probed into scandals and corruption, much to the annoyance of the show's protagonists.

- In 2001, The West Wing episode "The Indians in the Lobby" includes President Josiah Bartlet accosting the first lady by proclaiming "J'Accuse, mon petit fromage!"

- In 2003, New Directions published Israeli poet Aharon Shabtai's J'Accuse, a collection of poems drawn from two different collections, Politika and Artzenu and translated by Peter Cole.

- In 2008, film director Peter Greenaway released a documentary titled Rembrandt's J'Accuse. It is a companion piece to his film Nightwatching. It illustrates Greenaway's theory that Rembrandt's painting The Night Watch leaves clues to a murder by some of those portrayed.

- In 2012, Wayne Swan, the then Deputy Prime Minister of Australia, told Prime Minister Julia Gillard that she had given the "j'accuse speech" when she delivered her misogyny speech to the Australian Parliament, accusing Opposition Leader Tony Abbott of sexism and misogyny.[14]

- On October 7, 2013, the Cartoon Network show Adventure Time released an episode titled 'Box Prince'. In the episode the main protagonist "Finn" is attempting to aid the rightful prince of the Box Kingdom after discovering he was replaced by an impostor. When confronting the imposter prince he swings his arm towards the false leader and shouts "J'accuse!".

- On May 13, 2016, Brazilian columnist and politics professor Vladimir Safatle published an article in the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper titled "Nós acusamos" (we accuse) denouncing the several problems related to the removal from office of Brazil's president Dilma Rousseff.[15]

- On September 1, 2016, Argentinian lawyer and politician Margarita Stolbizer published a book titled Yo acuso ("I accuse") denouncing corruption during the government of Argentina's president Cristina Kirchner.[16]

- On June 9, 2017, The New York Times' White House correspondent Peter Baker wrote, in reference to the testimony of fired US FBI director James Comey before the US Senate's Intelligence Committee, "While delivered in calm, deliberate and unemotional terms, Mr. Comey’s testimony on Thursday was almost certainly the most damning j’accuse moment by a senior law enforcement official against a president [referring to Donald Trump] in a generation."[17]

- On April 19, 2020, UK Cabinet Minister Michael Gove used the phrase 'a j'accuse narrative' in response to media reporting of prime ministers absence from COBRA meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic [18]

- On June 3, 2020, The Atlantic, writing about President Trump's former Defense Secretary and retired Marine General James Mattis's comments in an interview in which Mattis strongly criticized President Trump on multiple points, characterizing them as Mattis's "j'accuse".[19]

References

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/j'accuse

- http://archive.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2008/03/30/when_zola_wrote_jaccuse/

- Alfred Dreyfus Biography (1859–1935). Biography.com (2007). Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- Burns, M. (1999). France and the Dreyfus Affair: A Documentary History. NY: St. Martin's College Publishing Group.

- Rothstein, E. "A Century-Old Court Case That Still Resonates" The New York Times (17 October 2007).

- Gopnik, Adam (2009). "Trial of the Century: Revisiting the Dreyfus affair". The New Yorker (28 September): 72–78. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- Shelokhonov, S. (2008). Biography for Émile Zola at the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- http://creativitydiaries.wordpress.com/2018/02/03/jaccuse-the-sins-of-the-artist/

- Zola, E. J'Accuse Archived 2008-07-15 at the Wayback Machine. L'Aurore (13 January 1898). Translation by Chameleon Translations. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- Bloy, Léon (1900). https://archive.org/details/jemaccusevignett00bloyuoft Je m'accuse...]. Paris: Édition de la Maison d'Art (1900)

- Alsop, J., & Alsop, S. "We Accuse!" Harper's (October, 1954).

- "Eichmann's handwritten clemency plea released in Israel". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "J'accuse" by Norman Podhoretz in Commentary Magazine, September 1982 edition.

- Sid Maher, "Emotional power of misogyny speech was lost on Gillard", The Australian, archived from the original on 27 July 2013, retrieved 5 September 2013

- "Nós acusamos". Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- "Stolbizer presentó su libro Yo acuso junto a Vidal y Massa". Retrieved 2016-09-01.

- "For Trump, the 'Cloud' Just Grew That Much Darker". Retrieved 2017-06-08.

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/19/michael-gove-fails-to-deny-pm-missed-five-coronavirus-cobra-meetings

- Goldberg, Jeffrey (3 June 2020). The Atlantic. The Atlantic Monthly Group https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2020/06/james-mattis-denounces-trump-protests-militarization/612640/. Retrieved 3 June 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

| Wikisource English translation of J'Accuse! |

Further reading

- Wilkes, Donald E., Jr. (11 February 1998). "'J'Accuse...!': Émile Zola, Alfred Dreyfus, and the greatest newspaper article in history". Flagpole Magazine. 12. p. 12. OCLC 30323514. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

External links

![]()