Le Docteur Pascal

Le Docteur Pascal (Doctor Pascal) is the twentieth and final novel of the Rougon-Macquart series by Émile Zola, first published in June 1893 by Charpentier.

| Author | Émile Zola |

|---|---|

| Translator | Ernest A. Vizetelly |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Series | Les Rougon-Macquart |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Charpentier (book form) |

Publication date | 1893 (book form) |

| Media type | Print (Serial, Hardback & Paperback) |

| Preceded by | La Débâcle |

| Followed by | n/a (last in series) |

Zola's plan for the Rougon-Macquart novels was to show how heredity and environment worked on the members of one family over the course of the Second Empire. He wraps up his heredity theories in this novel. Le docteur Pascal is furthermore essentially a story about science versus faith. The novel begins in 1872, after the fall of the Second Empire and the end of the reign of Emperor Napoleon III. The title character, Pascal Rougon (b. 1813), is the son of Pierre and Félicité Rougon, whose rise to power in the fictional town of Plassans is detailed in the first novel of the series La fortune des Rougon.

Plot summary

Pascal, a physician in Plassans for 30 years, has spent his life cataloging and chronicling the lives of his family based on his theories of heredity. Pascal believes that everyone's physical and mental health and development can be classified based on the interplay between innateness (reproduction of characteristics based in difference) and heredity (reproduction based in similarity). Using his own family as a case study, Pascal classifies the 30 descendants of his grandmother Adelaïde Fouque (Tante Dide) based on this model.

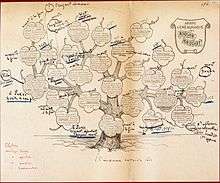

Pascal has developed a serum he hopes will cure hereditary and nervous diseases (including consumption) and improve if not prolong life. His niece Clotilde sees Pascal's work as denying the omnipotence of God and as a prideful attempt to comprehend the unknowable. She encourages him to destroy his work, but he refuses. (Like other members of the family, Pascal is somewhat obsessive in the pursuit of his passion.) Pascal's explains his goal as a scientist as laying the groundwork for happiness and peace by seeking and uncovering the truth, which he believes lies in the science of heredity. After he shows her the Rougon-Macquart family tree and demonstrates his refusal to sugarcoat the family's acts, Clotilde begins to agree with him. Her love for him solidifies her faith in his theories and his lifelong work.

Clotilde and Pascal eventually begin a romance, much to the chagrin of his mother Félicité. (She is less concerned about the incestuous nature of the relationship than by the fact that the two are living together out of wedlock.) Félicité wants to keep the family secrets buried at any cost, including several family skeletons living nearby: her alcoholic brother-in-law Antoine Macquart and her centenarian mother-in-law Tante Dide. When Clotilde's brother Maxime asks Clotilde to come to Paris, Félicité sees this as an opportunity to control Pascal and access his papers to destroy them.

Pascal suffers a series of heart attacks, and Clotilde is not able to return from Paris before he dies. Félicité immediately burns all of Pascal's scholarly work and the documents she considers incriminating. The novel, and the entire 20-novel series, concludes with the birth of Pascal and Clotilde's son and the hope placed on him for the future of the family.

Relation to the other Rougon-Macquart novels

As the last novel in the series, Le docteur Pascal ties up the loose ends of the remaining family members' lives. It is the only Rougon-Macquart novel that has all five generations of the family represented. Furthermore, it is the only novel in which a representative from each of the five generations dies: Tante Dide, Antoine Macquart, Pascal Rougon, Maxime Rougon/Saccard, and his son Charles.

Adelaïde Fouque (Tante Dide), the family ancestress, has lived in an asylum for 21 years. She dies at the age of 105 after witnessing the death of her great-great-grandson Charles. Her eldest son Pierre Rougon, Félicité's husband, died two years before the novel opens. Her younger son Antoine Macquart is a drunk. He dies during the course of the novel when his body, soaked with alcohol from a lifetime of drinking, catches fire - a fictional instance of spontaneous human combustion that may be compared to the death of Krook in Bleak House. Here again Zola touches, in a horrific manner, on the consequences of the excessive consumption of alcohol, a theme common to the entire Rougon-Macquart cycle.

Clotilde's brother Maxime lives in a Parisian mansion; he is suffering from ataxia and is being preyed upon by his father Aristide Saccard (see L'argent), who wants to get his hands on Maxime's money. Maxime has an illegitimate son named Charles, a hemophiliac, who bleeds to death on an afternoon visit to Tante Dide. Maxime too dies in the last pages of the novel.

In addition, we learn about the following:

- Eugène Rougon, Pascal's elder brother, is a deputy in the legislature where he continues to defend the fallen Emperor.

- Aristide Saccard, Pascal's younger brother, exiled to Belgium after the fall of the Banque Universelle (see L'argent), has returned to France. He is editor of a newspaper and is again building new and great businesses. After Maxime dies, he pockets his fortune for his own ends.

- Victor, Aristide's illegitimate son, has disappeared into the streets of Paris and left no trace (see L'argent).

- Sidonie Rougon, Pascal's sister, after a life of impropriety, now lives in "nunlike austerity" as the financial mistress of a home for unwed mothers.

- Octave Mouret and his wife Denise (Au bonheur des dames) have three children, a newborn, a sickly daughter and a robust and healthy son.

- Serge Mouret (La faute de l'Abbé Mouret), a parish priest, lives in religious seclusion with his sister Desirée. At the end of Le docteur Pascal, his death is imminent.

- Hélène Mouret and her husband Rambaud (Une page d'amour) continue to live in Marseilles, childless.

- Pauline Quenu (La joie de vivre) still lives at Bonneville, raising Lazare's son Paul (her uncle Chanteau having died) while Lazare, now a widower, has gone to America.

- Étienne Lantier (Germinal) was arrested for taking part in the violence of the Paris Commune and sent to New Caledonia, where he is married and has a child.

- Jean Macquart (La terre, La débâcle) has married and lives in a town near Plassans. He and his wife have two vital and healthy children, and they are expecting a third at the close of the series. The hope for any enduring strength of the family lies here, as with Clotilde and Pascal's son.

Publication and translation

The novel was translated into English by Ernest A. Vizetelly in 1894 (reprinted 1925 and 1995); by Mary J. Serrano in 1898 (reprinted 2005); and by Vladimir Kean in 1957.

Sources

- Brown, F. (1995). Zola: A life. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Zola, E. Le doctor Pascal, translated as Doctor Pascal by E.A. Vizetelly (1894).