Intercropping

Intercropping is a multiple cropping practice involving growing two or more crops in proximity. In other words, intercropping is the cultivation of two or more crops simultaneously on the same field. The most common goal of intercropping is to produce a greater yield on a given piece of land by making use of resources or ecological processes that would otherwise not be utilized by a single crop.

| Agriculture |

|---|

|

|

Categories

|

|

|

Potential benefits

Resource partitioning

Careful planning is required, taking into account the soil, climate, crops, and varieties. It is particularly important not to have crops competing with each other for physical space, nutrients, water, or sunlight. Examples of intercropping strategies are planting a deep-rooted crop with a shallow-rooted crop, or planting a tall crop with a shorter crop that requires partial shade. Inga alley cropping has been proposed as an alternative to the ecological destruction of slash-and-burn farming.[1]

When crops are carefully selected, other agronomic benefits are also achieved.

Mutualism

Planting two crops in close proximity can especially be beneficial when the two plants interact in a way that increases one or both of the plant's fitness (and therefore yield). For example, plants that are prone to tip over in wind or heavy rain (lodging-prone plants), may be given structural support by their companion crop.[2] Climbing plants such as black pepper can also benefit from structural support. Some plants are used to suppress weeds or provide nutrients.[3] Delicate or light-sensitive plants may be given shade or protection, or otherwise wasted space can be utilized. An example is the tropical multi-tier system where coconut occupies the upper tier, banana the middle tier, and pineapple, ginger, or leguminous fodder, medicinal or aromatic plants occupy the lowest tier.

Intercropping of compatible plants can also encourage biodiversity, by providing a habitat for a variety of insects and soil organisms that would not be present in a single-crop environment. These organisms may provide crops valuable nutrients, such as through nitrogen fixation.

Pest management

There are several ways in which increasing crop diversity may help improve pest management. For example, such practices may limit outbreaks of crop pests by increasing predator biodiversity.[4] Additionally, reducing the homogeneity of the crop can potentially increase the barriers against biological dispersal of pest organisms through the crop.

There are several ways pests can be controlled through intercropping:

- Trap cropping, this involves planting a crop nearby that is more attractive for pests compared to the production crop, the pests will target this crop and not the production crop.

- Repellant intercrops, an intercrop that has a repellent effect to certain pests can be used. This system involved the repellant crop masking the smell of the production crop in order to keep pests away from it.

- Push-pull cropping, this is a mixture of trap cropping and repellant intercropping. An attractant crop attracts the pest and a repellant crop is also used to repel the pest away.[5]

The degree of spatial and temporal overlap in the two crops can vary somewhat, but both requirements must be met for a cropping system to be an intercrop. Numerous types of intercropping, all of which vary the temporal and spatial mixture to some degree, have been identified.[6][7] These are some of the more significant types:

- Mixed intercropping, as the name implies, is the most basic form in which the component crops are totally mixed in the available space.

- Row cropping involves the component crops arranged in alternate rows. Variations include alley cropping, where crops are grown in between rows of trees, and strip cropping, where multiple rows, or a strip, of one crop are alternated with multiple rows of another crop. A new version of this is to intercrop rows of solar photovoltaic modules with agriculture crops. This practice is called agrivoltaics.[8]

- Temporal intercropping uses the practice of sowing a fast-growing crop with a slow-growing crop, so that the fast-growing crop is harvested before the slow-growing crop starts to mature.

- Further temporal separation is found in relay cropping, where the second crop is sown during the growth, often near the onset of reproductive development or fruiting, of the first crop, so that the first crop is harvested to make room for the full development of the second.

Limitations

Intercropping to reduce pest damage in agriculture, has been deployed with varying success. For example, while trap cropping has reduced pest densities at a commercial in experiments, it often fails to decrease pest densities deployed in large scale commercial landscapes.[9] Furthermore, increasing crop diversity through intercropping does not necessarily increase the presence of the predators of crop pests. In a systematic review of the literature, in 2008, in the studies examined, predators of pests tended only increased under crop diversification strategies in 53 percent of studies, and crop diversification only led to increased yield in only 32% of the studies.[10]

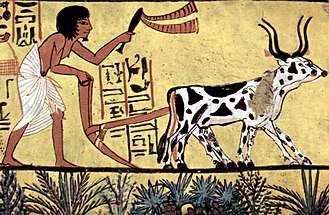

Gallery

See also

- Agrivoltaics

- Allotment garden

- Asset-based community development (ABCD)

- Community Food Security Coalition

- Community gardening

- Container garden

- Companion planting

- Ecological sanitation

- Food-feed system

- Forest gardening

- Gardening

- Green wall

- Monoculture

- Organic farming

- Permaculture

- Sustainable agriculture

References

- Elkan, Daniel. Slash-and-burn farming has become a major threat to the world's rainforest The Guardian 21 April 2004

- Trenbath, B.R. 1976. Plant interactions in mixed cropping communities. pp. 129–169 in R.I. Papendick, A. Sanchez, G.B. Triplett (Eds.), Multiple Cropping. ASA Special Publication 27. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI.

- Mt. Pleasant, Jane (2006). "The science behind the Three Sisters mound system: An agronomic assessment of an indigenous agricultural system in the northeast". In John E. Staller; Robert H. Tykot; Bruce F. Benz (eds.). Histories of maize: Multidisciplinary approaches to the prehistory, linguistics, biogeography, domestication, and evolution of maize. Amsterdam. pp. 529–537.

- Miguel Angel Altieri; Clara Ines Nicholls (2004). Biodiversity and Pest Management in Agroecosystems, Second Edition. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781560229230.

- "Controlling Pests with Plants: The power of intercropping - UVM Food Feed". UVM Food Feed. 2014-01-09. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Andrews, D.J., A.H. Kassam. 1976. The importance of multiple cropping in increasing world food supplies. pp. 1–10 in R.I. Papendick, A. Sanchez, G.B. Triplett (Eds.), Multiple Cropping. ASA Special Publication 27. American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI.

- Lithourgidis, A.S.; Dordas, C.A.; Damalas, C.A.; Vlachostergios, D.N. (2011). "Annual intercrops: an alternative pathway for sustainable agriculture" (PDF). Australian Journal of Crop Science. 5 (4): 396–410.

- Dinesh, Harshavardhan; Pearce, Joshua M. (2016-02-01). "The potential of agrivoltaic systems". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 54: 299–308. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.024.

- Holden, Matthew H.; Ellner, Stephen P.; Lee, Doo-Hyung; Nyrop, Jan P.; Sanderson, John P. (2012-06-01). "Designing an effective trap cropping strategy: the effects of attraction, retention and plant spatial distribution". Journal of Applied Ecology. 49 (3): 715–722. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02137.x.

- Poveda, Katja; Gómez, María Isabel; Martínez, Eliana (2008-12-01). "Diversification practices: their effect on pest regulation and production". Revista Colombiana de Entomología. 34 (2): 131–144.

- Improving nutrition through home gardening, Home Garden Technology Leaflet 13: Multilayer cropping, FAO, 2001

External links

- Intercropping at Washington State University