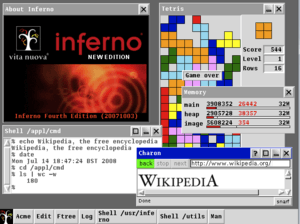

Inferno (operating system)

Inferno is a distributed operating system started at Bell Labs and now developed and maintained by Vita Nuova Holdings as free software.[2] Inferno was based on the experience gained with Plan 9 from Bell Labs, and the further research of Bell Labs into operating systems, languages, on-the-fly compilers, graphics, security, networking and portability. The name of the operating system and many of its associated programs, as well as that of the current company, were inspired by Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. In Italian, Inferno means "hell" — of which there are nine circles in Dante's Divine Comedy.

Inferno 4th Edition | |

| Developer | Bell Labs, Vita Nuova |

|---|---|

| Written in | C,[1] Limbo |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open-source |

| Initial release | 1996 |

| Latest release | 4th Edition / March 28, 2015 |

| Repository | |

| Platforms | ARM, PA-RISC, MIPS, PowerPC, SPARC, x86 |

| Kernel type | Virtual machine (Dis) |

| License | GPL, LGPL, MIT |

| Preceded by | Plan 9 |

| Official website | www |

Design principles

Inferno was created in 1995 by members of Bell Labs' Computer Science Research division to bring ideas of Plan 9 from Bell Labs to a wider range of devices and networks. Inferno is a distributed operating system based on three basic principles drawn from Plan 9:

- Resources as files: all resources are represented as files within a hierarchical file system

- Namespaces: a program's view of the network is a single, coherent namespace that appears as a hierarchical file system but may represent physically separated (locally or remotely) resources

- Standard communication protocol: a standard protocol, called Styx, is used to access all resources, both local and remote

To handle the diversity of network environments it was intended to be used in, the designers decided a virtual machine was a necessary component of the system. This is the same conclusion of the Oak project that became Java, but arrived at independently. The Dis virtual machine is a register machine intended to closely match the architecture it runs on, as opposed to the stack machine of the Java Virtual Machine. An advantage of this approach is the relative simplicity of creating a just-in-time compiler for new architectures.

The virtual machine provides memory management designed to be efficient on devices with as little as 1 MiB of memory and without memory-mapping hardware. Its garbage collector is a hybrid of reference counting and a real-time coloring collector that gathers cyclic data.[3]

The Inferno kernel contains the virtual machine, on-the-fly compiler, scheduler, devices, protocol stacks, and the name space evaluator for each process' file name space, and the root of the file system hierarchy. The kernel also includes some built-in modules that provide interfaces of the virtual operating system, such as system calls, graphics, security, and math modules.

The Bell Labs Technical Journal paper introducing Inferno listed several dimensions of portability and versatility provided by the OS:[4]

- Portability across processors: it currently runs on ARM, SGI MIPS, HP PA-RISC, IBM PowerPC, Sun SPARC, and Intel x86 architectures and is readily portable to others.

- Portability across environments: it runs as a stand-alone operating system on small terminals, and also as a user application under Bell Plan 9, MS Windows NT, Windows 95, and Unix (SGI Irix, Sun Solaris, FreeBSD, Apple Mac OS X, Linux, IBM AIX, HP-UX, Digital Tru64). In all of these environments, Inferno programs see an identical interface.

- Distributed design: the identical environment is established at the user's terminal and at the server, and each may import the resources (for example, the attached I/O devices or networks) of the other. Aided by the communications facilities of the run-time system, programs may be split easily (and even dynamically) between client and server.

- Minimal hardware requirements: it runs useful applications stand-alone on machines with as little as 1 MiB of memory, and does not require memory-mapping hardware.

- Portable programs: Inferno programs are written in the type-safe language Limbo and compiled to Dis bytecode, which can be run without modifications on all Inferno platforms.

- Dynamic adaptability: programs may, depending on the hardware or other resources available, load different program modules to perform a specific function. For example, a video player might use any of several different decoder modules.

These design choices were directed to provide standard interfaces that free content and service providers from concern of the details of diverse hardware, software, and networks over which their content is delivered.

Features

Inferno programs are portable across a broad mix of hardware, networks, and environments. It defines a virtual machine, known as Dis, that can be implemented on any real machine, provides Limbo, a type-safe language that is compiled to portable byte code, and, more significantly, it includes a virtual operating system that supplies the same interfaces whether Inferno runs natively on hardware or runs as a user program on top of another operating system.

A communications protocol called Styx is applied uniformly to access both local and remote resources, which programs use by calling standard file operations, open, read, write, and close. As of the fourth edition of Inferno, Styx is identical to Plan 9's newer version of its hallmark 9P protocol, 9P2000.

Commands

Most of the Inferno commands are very similar to Unix commands with the same name. The following list of commands is supported by Inferno.[5]

- 9win

- acme

- alphabet-abc

- alphabet-fs

- alphabet-grid

- alphabet-main

- ar

- asm

- auplay

- avr

- basename

- bind

- blur

- brutus

- cal

- calc

- calendar

- cat

- cd

- charon

- chgrp

- chmod

- cleanname

- cmp

- collab

- collab-clients

- comm

- cook

- cp

- cprof

- cpu

- crypt

- date

- dd

- deb

- diff

- disdep

- dmview

- du

- ebook

- echo

- emu

- env

- fc

- filename

- fmt

- fortune

- freq

- fs

- ftest

- ftree

- gettar

- grep

- grid-monitor

- grid-ns

- grid-query

- grid-register

- grid-session

- gzip

- idea

- intro

- itest

- keyboard

- kill

- limbo

- listen

- logon

- logwindow

- look

- ls

- m4

- man

- mash

- mash-make

- mash-tk

- math-misc

- mc

- mdb

- miniterm

- mk

- mkdir

- mprof

- mux

- mv

- netkey

- netstat

- ns

- nsbuild

- os

- p

- passwd

- plumb

- prof

- ps

- pwd

- rcmd

- read

- rm

- runas

- secstore

- sendmail

- sh

- sh-alphabet

- sh-arg

- sh-csv

- sh-expr

- sh-file2chan

- sh-mload

- sh-regex

- sh-sexprs

- sh-std

- sh-string

- sh-test

- sh-tk

- sleep

- sort

- spree-join

- stack

- stream

- strings

- sum

- tail

- tcs

- tee

- telnet

- time

- timestamp

- tiny

- tkcmd

- tktester

- toolbar

- touch

- tr

- tsort

- unicode

- uniq

- units

- uuencode

- vacget

- wc

- webgrab

- wish

- wm

- wm-misc

- wm-sh

- xd

- yacc

- zeros

History

| Date | Release | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Inferno Beta | Released by Bell Labs |

| May 1997 | Inferno Release 1.0 | Winter 1997 Bell Labs Technical Journal Article |

| July 1999 | Inferno 2nd Edition | Released by Lucent's Inferno Business Unit |

| June 2001 | Inferno 3rd Edition | Released by Vita Nuova |

| 2004 | Inferno 4th Edition | Open Source release; changes to many interfaces (incompatible with earlier editions); includes support for 9P2000. |

Inferno is a descendant of Plan 9, and shares many design concepts and even source code in the kernel, particularly around devices and the Styx/9P2000 protocol. Inferno shares with Plan 9 the Unix heritage from Bell Labs and the Unix philosophy. Many of the command line tools in Inferno were Plan 9 tools that were translated to Limbo.

In the mid-1990s, Plan 9 development was set aside in favor of Inferno.[6] The new system's existence was leaked by Dennis Ritchie in early 1996, after less than a year of development on the system, and publicly presented later that year as a competitor to Java. At the same time, Bell Labs' parent company AT&T licensed Java technology from Sun Microsystems.[7]

In March–April 1997 IEEE Internet Computing included an advertisement for Inferno networking software. It claimed that various devices could communicate over "any network" including the Internet, telecommunications and LANs. The advertisement stated that video games could talk to computers,–a PlayStation was pictured–cell phones could access email and voice mail was available via TV.

Lucent used Inferno in at least two internal products: the Lucent VPN Firewall Brick, and the Lucent Pathstar phone switch. They initially tried to sell source code licenses of Inferno but found few buyers. Lucent did little marketing and missed the importance of the Internet and Inferno's relation to it. During the same time Sun Microsystems was heavily marketing its own Java programming language, which was targeting a similar market, with analogous technology, that worked in web browsers and also filled the demand for object-oriented languages popular at that time. Lucent licensed Java from Sun, claiming that all Inferno devices would be made to run Java. A Java byte code to Dis byte code translator was written to facilitate that. However, Inferno still did not find customers.

The Inferno Business Unit closed after three years, and was sold to Vita Nuova. Vita Nuova continued development and offered commercial licenses to the complete system, and free downloads and licenses (not GPL compatible) for all of the system except the kernel and VM. They ported the software to new hardware and focused on distributed applications. Eventually, Vita Nuova released the source under the GPL license and the Inferno operating system is now a Free/Libre/Open Source Software project.

Ports

Inferno runs directly on native hardware and also as an application providing a virtual operating system which runs on other platforms. Programs can be developed and run on all Inferno platforms without modification or recompilation.

Native ports include these architectures: x86, MIPS, ARM, PowerPC, SPARC.

Hosted or virtual OS ports include: Microsoft Windows, Linux, FreeBSD, Plan 9, Mac OS X, Solaris, IRIX, UnixWare.

Inferno can also be hosted by a plugin to Internet Explorer.[8] Vita Nuova said that plugins for other browsers were under development, but they were never released.[9]

Inferno has also been ported to Openmoko,[10] Nintendo DS,[11][12] SheevaPlug,[13] and Android.[14]

License

Inferno 4th edition was released in early 2005 as free software. Specifically, it was dual-licensed under two licenses.[15] Users could either obtain it under a set of free software licenses, or they could obtain it under a proprietary license. In the case of the free software license scheme, different parts of the system were covered by different licenses, including the GNU General Public License, the GNU Lesser General Public License, the Lucent Public License, and the MIT License. Subsequently, Vita Nuova has made it possible to acquire the entire system (excluding the fonts, which are sub-licensed from Bigelow and Holmes) under the GPLv2. All three license options are currently available.

See also

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs

- Unix

- Language-based system

- Singularity (operating system) Similar experimental operating system from Microsoft Research

References

- Dorward, Sean; Pike, Rob; Presotto, David Leo; Ritchie, Dennis M.; Trickey, Howard; Winterbottom, Phil (1997). "The Inferno Operating System". Inferno Documentation. Vita Nuova. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- "inferno-os / inferno-os — Bitbucket". Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- Lorenz Huelsbergen and Phil Winterbottom. "Very Concurrent Mark and Sweep Garbage Collection without Fine-Grain Synchronization" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Inferno Operating System" (papers). Vita nuova. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - http://man.cat-v.org/inferno/1/

- Pontin, Jason (19 February 1996). "AT&T reveals plans for Java competitor". InfoWorld. p. 3.

- Hayes, Frank (19 February 1996). "Bell Lab's Inferno aims to rival Java". Computerworld. p. 6.

- "Supporting code to allow Inferno to act as a plugin in various browsers".

- Plugins, Vita Nuova.

- "inferno-openmoko - inferno for openmoko neo freerunner - Google Project Hosting". Code.google.com. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- "inferno-ds - Inferno Kernel for the Nintendo DS - Google Project Hosting". Code.google.com. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- "inferno-ds: Native Inferno Kernel for the Nintendo DS". bitbucket.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- "inferno-kirkwood - Inferno for the Marvell Kirkwood/Sheevaplug - Google Project Hosting". Code.google.com. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- inferno (2011-09-29). "floren / inferno / wiki / Home — Bitbucket". Bitbucket.org. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- "Inferno License Terms".

Further reading

- Stanley-Marbell, Phillip (2003). "Inferno Programming with Limbo". Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-84352-7. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) describes the 3rd edition of the Inferno operating system, though it focuses more on the Limbo language and its interfaces to the Inferno system, than on the Inferno system itself. For example, it provides little information on Inferno's versatile command shell, which is understandable since it is a programming language textbook. - Stuart, Brian (2008). Principles of Operating Systems: Design and Applications. Course Technology. ISBN 1-4188-3769-5., uses Inferno for examples of operating system design.

- Atkins, Martin; Forsyth, Charles; Pike, Rob; Trickey, Howard. "The Inferno Programming Book: An Introduction to Programming for the Inferno Distributed System". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) was intended to provide an operating-system-centric point of view, but was never completed.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inferno (operating system). |

- Documentation papers for the latest inferno release.

- Source code repo, at Bitbucket.

- Inferno Fourth Edition Download, including source code.

- Inferno manual pages.

- Other Inferno documents of interest.

- Mailing list and other resources.

- Ninetimes: News and articles about Inferno, Plan 9 and related technologies.

- Inferno programmer's notebook - A journal made by an Inferno developer.

- Try Inferno: free, in-browser access to a live Inferno system.

- Inferno OS to Raspberry Pi Labs: Porting Inferno OS to Raspberry Pi

Ports

- Inferno for the Nintendo DS

- Inferno for the Marvell Kirkwood/Sheevaplug

- Inferno on OLPC

- Inferno port to the Openmoko neo freerunner

- Inferno port to the Raspberry Pi

Of Historical Interest