Imagination

Imagination is the ability to produce and simulate novel objects, peoples and ideas in the mind without any immediate input of the senses. It is also described as the forming of experiences in one's mind, which can be re-creations of past experiences such as vivid memories with imagined changes, or they can be completely invented and possibly fantastic scenes.[1] Imagination helps make knowledge applicable in solving problems and is fundamental to integrating experience and the learning process.[2][3][4][5] A basic training for imagination is listening to storytelling (narrative),[2][6] in which the exactness of the chosen words is the fundamental factor to "evoke worlds".[7]

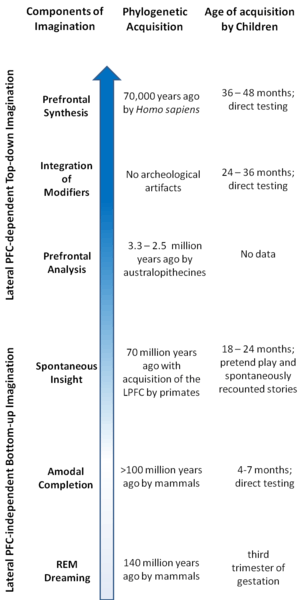

Imagination is a cognitive process used in mental functioning and sometimes used in conjunction with psychological imagery. It is considered as such because it involves thinking about possibilities.[8] The cognate term of mental imagery may be used in psychology for denoting the process of reviving in the mind recollections of objects formerly given in sense perception. Since this use of the term conflicts with that of ordinary language, some psychologists have preferred to describe this process as "imaging" or "imagery" or to speak of it as "reproductive" as opposed to "productive" or "constructive" imagination. Constructive imagination is further divided into active imagination driven by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and spontaneous PFC-independent imagination such as REM-sleep dreaming, daydreaming, hallucinations, and spontaneous insight. The active types of imagination include integration of modifiers, and mental rotation. Imagined images, both novel and recalled, are seen with the "mind's eye".

Imagination, however, is not considered to be exclusively a cognitive activity because it is also linked to the body and place, particularly that it also involves setting up relationships with materials and people, precluding the sense that imagination is locked away in the head.[9]

Imagination can also be expressed through stories such as fairy tales or fantasies. Children often use such narratives and pretend play in order to exercise their imaginations. When children develop fantasy they play at two levels: first, they use role playing to act out what they have developed with their imagination, and at the second level they play again with their make-believe situation by acting as if what they have developed is an actual reality.[10]

The mind's eye

The notion of a "mind's eye" goes back at least to Cicero's reference to mentis oculi during his discussion of the orator's appropriate use of simile.[11]

In this discussion, Cicero observed that allusions to "the Syrtis of his patrimony" and "the Charybdis of his possessions" involved similes that were "too far-fetched"; and he advised the orator to, instead, just speak of "the rock" and "the gulf" (respectively) — on the grounds that "the eyes of the mind are more easily directed to those objects which we have seen, than to those which we have only heard".[12]

The concept of "the mind's eye" first appeared in English in Chaucer's (c.1387) Man of Law's Tale in his Canterbury Tales, where he tells us that one of the three men dwelling in a castle was blind, and could only see with "the eyes of his mind"; namely, those eyes "with which all men see after they have become blind".[13]

The condition of not being able to internally visualize (the lack of a ”mind’s eye”) is called Aphantasia.

Description

The common use of the term is for the process of forming new images in the mind that have not been previously experienced with the help of what has been seen, heard, or felt before, or at least only partially or in different combinations. This could also be involved with thinking out possible or impossible outcomes of something or someone in life's abundant situations and experiences. Some typical examples follow:

- Fairy tale

- Fiction

- A form of verisimilitude often invoked in fantasy and science fiction invites readers to pretend such stories are true by referring to objects of the mind such as fictional books or years that do not exist apart from an imaginary world.

Imagination, not being limited to the acquisition of exact knowledge by the requirements of practical necessity is largely free from objective restraints. The ability to imagine one's self in another person's place is very important to social relations and understanding. Albert Einstein said, "Imagination ... is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world."[14]

The same limitations beset imagination in the field of scientific hypothesis. Progress in scientific research is due largely to provisional explanations which are developed by imagination, but such hypotheses must be framed in relation to previously ascertained facts and in accordance with the principles of the particular science.

Imagination is an experimental partition of the mind used to develop theories and ideas based on functions. Taking objects from real perceptions, the imagination uses complex If-functions that involve both Semantic and Episodic memory to develop new or revised ideas.[15] This part of the mind is vital to developing better and easier ways to accomplish old and new tasks. In sociology, Imagination is used to part ways with reality and have an understanding of social interactions derived from a perspective outside of society itself. This leads to the development of theories through questions that wouldn't usually be asked. These experimental ideas can be safely conducted inside a virtual world and then, if the idea is probable and the function is true, the idea can be actualized in reality. Imagination is the key to new development of the mind and can be shared with others, progressing collectively.

Regarding the volunteer effort, imagination can be classified as:

- involuntary (the dream from the sleep, the daydream)

- voluntary (the reproductive imagination, the creative imagination, the dream of perspective)

Psychology

Psychologists have studied imaginative thought, not only in its exotic form of creativity and artistic expression but also in its mundane form of everyday imagination.[16] Ruth M.J. Byrne has proposed that everyday imaginative thoughts about counterfactual alternatives to reality may be based on the same cognitive processes on which rational thoughts are also based.[17] Children can engage in the creation of imaginative alternatives to reality from their very early years.[18] Cultural psychology is currently elaborating a view of imagination as a higher mental function involved in a number of everyday activities both at the individual and collective level[19] that enables people to manipulate complex meanings of both linguistic and iconic forms in the process of experiencing.

The phenomenology of imagination is discussed In The Imaginary: A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination (French: L'Imaginaire: Psychologie phénoménologique de l'imagination), also published under the title The Psychology of the Imagination, is a 1940 book by Jean-Paul Sartre, in which he propounds his concept of the imagination and discusses what the existence of imagination shows about the nature of human consciousness.[20]

The imagination is also active in our perception of photographic images in order to make them appear real.[21]

Memory

Memory and mental imagery, often seen as a part of the process of imagination, have been shown to be affected by one another.[22] "Images made by functional magnetic resonance imaging technology show that remembering and imagining sends blood to identify parts of the brain."[22] Various psychological factors can influence the mental processing of and can to heighten the chance of the brain to retain information as either long-term memories or short-term memories. John Sweller indicated that experiences stored as long-term memories are easier to recall, as they are ingrained deeper in the mind. Each of these forms require information to be taught in a specific manner so as to use various regions of the brain when being processed.[23] This information can potentially help develop programs for young students to cultivate or further enhance their creative abilities from a young age. The neocortex and thalamus are responsible for controlling the brain's imagination, along with many of the brain's other functions such as consciousness and abstract thought.[24] Since imagination involves many different brain functions, such as emotions, memory, thoughts, etc., portions of the brain where multiple functions occur—such as the thalamus and neocortex—are the main regions where imaginative processing has been documented.[25] The understanding of how memory and imagination are linked in the brain, paves the way to better understand one's ability to link significant past experiences with their imagination. Aphantasia is a disease that makes you not imagine.

Perception

Piaget posited that perceptions depend on the world view of a person. The world view is the result of arranging perceptions into existing imagery by imagination. Piaget cites the example of a child saying that the moon is following her when she walks around the village at night. Like this, perceptions are integrated into the world view to make sense. Imagination is needed to make sense of perceptions.[26]

Versus belief

Imagination is different from belief because the subject understands that what is personally invented by the mind does not necessarily affect the course of action taken in the apparently shared world, while beliefs are part of what one holds as truths about both the shared and personal worlds. The play of imagination, apart from the obvious limitations (e.g. of avoiding explicit self-contradiction), is conditioned only by the general trend of the mind at a given moment. Belief, on the other hand, is immediately related to practical activity: it is perfectly possible to imagine oneself a millionaire, but unless one believes it one does not, therefore, act as such. Belief endeavors to conform to the subject's experienced conditions or faith in the possibility of those conditions; whereas imagination as such is specifically free.

The dividing line between imagination and belief varies widely in different stages of technological development. Thus in more extreme cases, someone from a primitive culture who ill frames an ideal reconstruction of the causes of his illness, and attributes it to the hostile magic of an enemy based on faith and tradition rather than science. In ignorance of the science of pathology the subject is satisfied with this explanation, and actually believes in it, sometimes to the point of death, due to what is known as the nocebo effect. It follows that the learned distinction between imagination and belief depends in practice on religion, tradition, and culture.

Brain activation

A study using fMRI while subjects were asked to imagine precise visual figures, to mentally disassemble them, or mentally blend them, showed activity in the occipital, frontoparietal, posterior parietal, precuneus, and dorsolateral prefrontal regions of the subject's brains.[27]

Evolution of imagination

Phylogenetic acquisition of imagination was a gradual process. The simplest form of imagination, REM-sleep dreaming, evolved in mammals with acquisition of REM sleep 140 million years ago.[28] Spontaneous insight improved in primates with acquisition of the lateral prefrontal cortex 70 million years ago. After hominins split from the chimpanzee line 6 million years ago they further improved their imagination. Prefrontal analysis was acquired 3.3 million years ago when hominins started to manufacture Mode One stone tools.[29] Progress in stone tools culture to Mode Two stone tools by 2 million years ago signify remarkable improvement of prefrontal analysis. The most advanced mechanism of imagination, prefrontal synthesis, was likely acquired by humans around 70,000 years ago and resulted in behavioral modernity.[30] This leap toward modern imagination has been characterized by paleoanthropologists as the "Cognitive revolution",[31] "Upper Paleolithic Revolution",[32] and the "Great Leap Forward".[33]

As a reality

The world as experienced is an interpretation of data arriving from the senses; as such, it is perceived as real by contrast to most thoughts and imaginings. Users of hallucinogenic drugs are said to have a heightened imagination, or perhaps, a kind of heightened imaginative output. This difference is only one of degree and can be altered by several historic causes, namely changes to brain chemistry, hypnosis or other altered states of consciousness, meditation, many hallucinogenic drugs, and electricity applied directly to specific parts of the brain. The difference between imagined and perceived reality can be proven by psychosis. Many mental illnesses can be attributed to this inability to distinguish between the sensed and the internally created worlds. Some cultures and traditions even view the apparently shared world as an illusion of the mind as with the Buddhist Maya, or go to the opposite extreme and accept the imagined and dreamed realms as of equal validity to the apparently shared world as the Australian Aborigines do with their concept of dreamtime.

Imagination, because of having freedom from external limitations, can often become a source of real pleasure and unnecessary suffering. Consistent with this idea, imagining pleasurable and fearful events is found to engage emotional circuits involved in emotional perception and experience.[34] A person of vivid imagination often suffers acutely from the imagined perils besetting friends, relatives, or even strangers such as celebrities. Also crippling fear can result from taking an imagined painful future too seriously.

See also

- Artificial imagination

- Cognitive dissonance

- Creative visualization

- Creativity

- Decatastrophizing

- Exaggeration

- Fantasy (psychology)

- Fictional countries

- Guided imagery

- Imagery

- The Imaginary (psychoanalysis)

- Imaginary (sociology)

- Imagination Age

- Imagination inflation

- Intuition (psychology)

- Mental image

- Mimesis

- Sociological imagination

- Truth

- Tulpa

- Verisimilitude

References

- Szczelkun, Stefan (2018-03-03). SENSE THINK ACT: a collection of exercises to experience total human ability. Stefan Szczelkun. ISBN 9781870736107.

- Norman 2000 pp. 1-2

- Brian Sutton-Smith 1988, p. 22

- Archibald MacLeish 1970, p. 887

- Kieran Egan 1992, pp. 50

- Northrop Frye 1963, p. 49

- As noted by Giovanni Pascoli

- Byrne, Ruth (2007). The Rational Imagination: How People Create Alternatives to Reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 38. ISBN 978-0262025843.

- Janowski, Dr Monica; Ingold, Professor Tim (2012-09-01). Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present and Future. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9781409461449.

- Laurence Goldman (1998). Child's play: myth, mimesis and make-believe. Oxford New York: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85973-918-1.

Basically what this means is that the children use their make-believe situation and act as if what they are acting out is from a reality that already exists even though they have made it up.imagination comes after story created.

- Cicero, De Oratore, Liber III: XLI: 163.

- J.S. (trans. and ed.), Cicero on Oratory and Orators, Harper & Brothers, (New York), 1875: Book III, C.XLI, p.239.

- The Man of Laws Tale, lines 550-553.

- Viereck, George Sylvester (October 26, 1929). "What life means to Einstein: an interview". The Saturday Evening Post.

- Devitt, Aleea L.; Addis, Donna Rose; Schacter, Daniel L. (2017-10-01). "Episodic and semantic content of memory and imagination: A multilevel analysis". Memory & Cognition. 45 (7): 1078–1094. doi:10.3758/s13421-017-0716-1. ISSN 1532-5946. PMC 5702280. PMID 28547677.

- Ward, T.B., Smith, S.M, & Vaid, J. (1997). Creative thought. Washington DC: APA

- Byrne, R.M.J. (2005). The Rational Imagination: How People Create Alternatives to Reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Harris, P. (2000). The work of the imagination. London: Blackwell.

- Tateo, L. (2015). Giambattista Vico and the psychological imagination. Culture and Psychology, vol. 21(2):145-161.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (1995). The psychology of imagination. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415119542. OCLC 34102867.

- Wilson, John G. (2016-12-01). "Sartre and the Imagination: Top Shelf Magazines". Sexuality & Culture. 20 (4): 775–784. doi:10.1007/s12119-016-9358-x. ISSN 1095-5143.

- Long, Priscilla (2011). My Brain On My Mind. p. 27. ISBN 978-1612301365.

- Leahy, Wayne; John Sweller (5 June 2007). "The Imagination Effect Increases with an Increased Intrinsic Cognitive Load". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 22 (2): 273–283. doi:10.1002/acp.1373.

- "Welcome to Brain Health and Puzzles!". Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- "Welcome to ScienceForums.Net!".

- Piaget, J. (1967). The child's conception of the world. (J. & A. Tomlinson, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. BF721 .P5 1967X

- Alexander Schlegel, Peter J. Kohler, Sergey V. Fogelson, Prescott Alexander, Dedeepya Konuthula, and Peter Ulric Tse (Sep 16, 2013) Network structure and dynamics of the mental workspace PNAS early edition

- Hobson, J. Allan (1 October 2009). "REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10 (11): 803–813. doi:10.1038/nrn2716. PMID 19794431.

- Harmand, Sonia; Lewis, Jason E.; Feibel, Craig S.; Lepre, Christopher J.; Prat, Sandrine; Lenoble, Arnaud; Boës, Xavier; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Brenet, Michel; Arroyo, Adrian; Taylor, Nicholas; Clément, Sophie; Daver, Guillaume; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Leakey, Louise; Mortlock, Richard A.; Wright, James D.; Lokorodi, Sammy; Kirwa, Christopher; Kent, Dennis V.; Roche, Hélène (20 May 2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961.

- Vyshedsky, Andrey (2019). "Neuroscience of Imagination and Implications for Human Evolution" (PDF). Curr Neurobiol. 10 (2): 89–109.

- Harari, Yuval N. (2014). Sapiens : a brief history of humankind. London. ISBN 9781846558245. OCLC 890244744.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (October 2002). "The Upper Paleolithic Revolution". Annual Review of Anthropology. 31 (1): 363–393. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085416. ISSN 0084-6570.

- Diamond, Jared M. (2006). The third chimpanzee : the evolution and future of the human animal. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0060845503. OCLC 63839931.

- Costa, VD, Lang, PJ, Sabatinelli, D, Bradley MM, and Versace, F (2010). "Emotional imagery: Assessing pleasure and arousal in the brain's reward circuitry". Human Brain Mapping. 31 (9): 1446–1457. doi:10.1002/hbm.20948. PMC 3620013. PMID 20127869.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: imagination |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Imagination. |

Further reading

- Books

- Byrne, R. M. J. (2005). The Rational Imagination: How People Create Alternatives to Reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- Egan, Kieran (1992). Imagination in Teaching and Learning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fabiani, Paolo "The Philosophy of the Imagination in Vico and Malebranche". F.U.P. (Florence UP), Italian edition 2002, English edition 2009.

- Frye, N. (1963). The Educated Imagination. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Norman, Ron (2000) Cultivating Imagination in Adult Education Proceedings of the 41st Annual Adult Education Research.

- Salazar, Noel B. (2010) Envisioning Eden: Mobilizing imaginaries in tourism and beyond. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Sutton-Smith, Brian. (1988). In Search of the Imagination. In K. Egan and D. Nadaner (Eds.), Imagination and Education. New York, Teachers College Press.

- Wilson, J. G. (2016). "Sartre and the Imagination: Top Shelf Magazines". Sexuality & Culture. 20 (4): 775–784. doi:10.1007/s12119-016-9358-x.

- Articles

- Salazar, Noel B. (2020). On imagination and imaginaries, mobility and immobility: Seeing the forest for the trees. Culture & Psychology 1-10.

- Salazar, Noel B. (2011). "The power of imagination in transnational mobilities". Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power. 18 (6): 576–598. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2011.672859.

- Watkins, Mary: "Waking Dreams" [Harper Colophon Books, 1976] and "Invisible Guests - The Development of Imaginal Dialogues" [The Analytic Press, 1986]

- Moss, Robert: "The Three "Only" Things: Tapping the Power of Dreams, Coincidence, and Imagination" [New World Library, September 10, 2007]

Three philosophers for whom imagination is a central concept are Kendall Walton, John Sallis and Richard Kearney. See in particular:

- Kendall Walton, Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Harvard University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-674-57603-9 (pbk.).

- John Sallis, Force of Imagination: The Sense of the Elemental (2000)

- John Sallis, Spacings-Of Reason and Imagination. In Texts of Kant, Fichte, Hegel (1987)

- Richard Kearney, The Wake of Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press (1988); 1st Paperback Edition- (ISBN 0-8166-1714-7)

- Richard Kearney, "Poetics of Imagining: Modern to Post-modern." Fordham University Press (1998)

External links

![]()

- Imagination on In Our Time at the BBC

- Imagination, Mental Imagery, Consciousness, and Cognition: Scientific, Philosophical and Historical Approaches

- Two-Factor Imagination Scale at the Open Directory Project

- "The neuroscience of imagination". TED-Ed.