Hysterosalpingography

Hysterosalpingography (HSG), also known as uterosalpingography,[1] is a radiologic procedure to investigate the shape of the uterine cavity and the shape and patency of the fallopian tubes. This means it is a special x-ray using dye to look at the womb (uterus) and Fallopian tubes.[2] It injects a radio-opaque material into the cervical canal and usually fluoroscopy with image intensification. A normal result shows the filling of the uterine cavity and the bilateral filling of the fallopian tube with the injection material. To demonstrate tubal rupture, spillage of the material into the peritoneal cavity needs to be observed. It has vital role in treatment of infertility especially in case of fallopian tube blockade.

| Hysterosalpingography | |

|---|---|

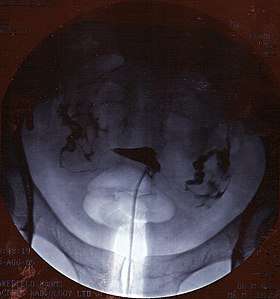

A normal hysterosalpingogram. Note the catheter entering at the bottom of the screen, and the contrast medium filling the uterine cavity (small triangle in the center). | |

| Other names | Uterosalpingography |

| ICD-9-CM | 87.8 |

| MeSH | D007047 |

| MedlinePlus | 003404 |

Procedure

The procedure involves X-rays. It should be done in the follicular phase of the cycle.[3] It is contraindicated in pregnancy. It is useful to diagnose uterine malformations, Asherman's syndrome, tubal occlusion and pelvic inflammatory disease[4] and used extensively in the work-up of infertile women.[5] It has been claimed that the chance of pregnancy increases after HSG has been performed.[6][5][7] Using catheters, an interventional radiologist or specifically trained radiographer can open tubes that are proximally occluded.

The test is usually done with radiographic contrast medium (dye) injected into the uterine cavity through the vagina and cervix. If the fallopian tubes are open the contrast medium will fill the tubes and spill out into the abdominal cavity. It can be determined whether the fallopian tubes are open or blocked and whether the blockage is located at the junction of the tube and the uterus (proximal) or whether it is at the end of the fallopian tube (distal).

The HSG can be painful, so analgesics may be administered before and/or after the procedure to reduce pain. Many doctors will also prescribe an antibiotic prior to the procedure to reduce the risk of an infection.

Therapeutic benefit

HSG is considered a diagnostic procedure, but may also have therapeutic benefits for infertility treatment. When oil-based contrast is used rates of pregnancy increase by about 10% compared to water-based contrast.[5] A meta-analysis revealed 3.6 times greater odds (OR = 3.6) of pregnancy with oil-based contrast compared to no hysterosalpingography.[7] This effect is thought to be due to tubal flushing with the oil-based contrast rather than the imaging procedure, itself.

Contraindications

HSG should never be performed on pregnant women. Complications of the procedure include infection,[2] allergic reactions to the materials used[2], intravasation of the material, and, if oil-based material is used, embolisation. Air can also be accidentally instilled into the uterine cavity by the operator, thus limiting the exam due to iatrogenically induced filling defects. This can be overcome by administering the Tenzer Tilt, which will demonstrate movement of the air bubbles to the non-dependent portion of the uterine cavity.

History

For the first HSG Carey used collergol in 1914. Lipiodol was introduced by Sicard and Forestier in 1924 and remained a popular contrast medium for many decades.[8] Later, water-soluble contrast material was generally preferred as it avoided the possible complication of oil embolism.

Follow up

If the HSG indicates further investigations are warranted, a laparoscopy, assisted by hysteroscopy, may be advised to visualise the area in three dimensions, with the potential to resolve minor issues within the same procedure.

See also

References

- "Hysterosalpingography (Uterosalpingography)". RadiologyInfo. June 8, 2016.

- "Hysterosalpingography: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Baramki T (2005). "Hysterosalpingography". Fertil Steril. 83 (6): 1595–606. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.050. PMID 15950625.

- Ljubin-Sternak, Suncanica; Mestrovic, Tomislav (2014). "Review: Clamydia trachonmatis and Genital Mycoplasmias: Pathogens with an Impact on Human Reproductive Health". Journal of Pathogens. 2014 (183167): 183167. doi:10.1155/2014/183167. PMC 4295611. PMID 25614838.

- Dreyer, Kim; Rijswijk, Joukje van; Mijatovic, Velja; Goddijn, Mariëtte; Verhoeve, Harold R.; Rooij, Ilse A.J. van; Hoek, Annemieke; Bourdrez, Petra; Nap, Annemiek W. (2017-05-18). "Oil-Based or Water-Based Contrast for Hysterosalpingography in Infertile Women". New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (21): 2043–2052. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1612337. PMID 28520519.

- "Hysterosalpingogram". WebMD Medical Reference.

- Mohiyiddeen, Lamiya; Hardiman, Anne; Fitzgerald, Cheryl; Hughes, Edward; Mol, Ben Willem J.; Johnson, Neil; Watson, Andrew (2015). "Tubal flushing for subfertility | Cochrane". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD003718. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003718.pub4. PMC 7133784. PMID 25929235.

- Bendick A. J. (1947). "Present Status of Hysterosalpingography". Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital, New York. 14 (3): 739.