Hyacinth macaw

The hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus), or hyacinthine macaw, is a parrot native to central and eastern South America. With a length (from the top of its head to the tip of its long pointed tail) of about one meter it is longer than any other species of parrot. It is the largest macaw and the largest flying parrot species, though the flightless kakapo of New Zealand can outweigh it at up to 3.5 kg. While generally easily recognized, it could be confused with the smaller Lear's macaw. Habitat loss and the trapping of wild birds for the pet trade have taken a heavy toll on their population in the wild, so the species is classified as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List,[1] and it is protected by its listing on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

| Hyacinth macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| At the Disney's Animal Kingdom Park, Florida | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Anodorhynchus |

| Species: | A. hyacinthinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus (Latham, 1790) | |

| |

Taxonomy

English physician, ornithologist, and artist John Latham first described the hyacinth macaw in 1790 under the binomial name Psittacus hyacinthinus based on a taxidermic specimen sent to England.[2] It is one of two extant and one probably extinct species of the South American macaw genus Anodorhynchus.

Description

The largest parrot by length in the world, the hyacinth macaw is 1 m (3.3 ft) long from the tip of its tail to the top of its head and weighs 1.2–1.7 kg (2.6–3.7 lb).[3][4] Each wing is 38.8–42.5 cm (15.3–16.7 in) long.[3] The tail is long and pointed.[3] Its feathers are entirely blue, lighter above. However, the neck feathers can sometimes be slightly grey. The ring around the parrots eyes and area just underneath the beak are a strong, vibrant yellow.

Close-up of head

Close-up of head A skeleton exhibited at Dvůr Králové Zoo in Dvůr Králové nad Labem, Czech Republic

A skeleton exhibited at Dvůr Králové Zoo in Dvůr Králové nad Labem, Czech Republic

Behaviour

Food and feeding

The majority of the hyacinth macaw diet is Brazil nuts, from native palms, such as acuri and bocaiuva palms.[5] They have very strong beaks for eating the kernels of hard nuts and seeds. Their strong beaks are even able to crack coconuts, the large brazil nut pods, and macadamia nuts. The birds also boast dry, smooth tongues with a bone inside them that makes them an effective tool for tapping into fruits.[6] The acuri nut is so hard, the parrots cannot feed on it until it has passed through the digestive system of cattle.[5] In addition, they eat fruits and other vegetable matter. The hyacinth macaw generally eats fruits, nuts, nectar, and various kinds of seeds. Also, they travel for the ripest of foods over a vast area.[7]

In the Pantanal, hyacinth macaws feed almost exclusively on the nuts of Acrocomia aculeata and Attalea phalerata palm trees. This behaviour was recorded by the English naturalist Henry Walter Bates in his 1863 book The Naturalist on the River Amazons, where he wrote that

It flies in pairs, and feeds on the hard nuts of several palms, but especially of the Mucuja (Acrocomia lasiospatha). These nuts, which are so hard as to be difficult to break with a heavy hammer, are crushed to a pulp by the powerful beak of this macaw.

— Bates[8]

Charles Darwin remarked on Bates's account of the species, calling it a "splendid bird" with its "enormous beak" able to feed on these palm nuts.[9]

Tool use

Limited tool use has been observed in both wild and captive hyacinth macaws. Reported sightings of tool use in wild parrots go as far back as 1863. Examples of tool use that have been observed usually involve a chewed leaf or pieces of wood. Macaws often incorporate these items when feeding on harder nuts. Their use allows the nuts the macaws eat to remain in position (prevent slipping) while they gnaw into it. It is not known whether this is learned social behavior or an innate trait, but observation on captive macaws shows that hand-raised macaws exhibit this behavior, as well. Comparisons show that older macaws were able to open seeds more efficiently.[10]

Reproduction

.jpg)

Nesting takes place between July and December, with nests constructed in tree cavities or cliff faces depending on the habitat.[11] In the Pantanal region, 90% of nests are constructed in the manduvi tree (Sterculia apetala). The hyacinth macaw depends on the toucan, for its livelihood. The toucan contributes largely to seed dispersal of the manduvi tree that the macaw needs for reproduction.[12] However, the toucan is responsible for dispersing 83% of the seeds of Sterculia apetala, but also consumes 53% of eggs preyed.[13] Hollows of sufficient size are only found in trees around 60 years of age or older, and competition is fierce.[12] Existing holes are enlarged and then partially filled with wood chips.[14] The clutch size is one or two eggs,[5] although usually only one fledgling survives[5] as the second egg hatches several days after the first, and the smaller fledgling cannot compete with the firstborn for food. A possible explanation for this behavior is what is called the insurance hypothesis. The macaw lays more eggs than can be normally fledged to compensate for earlier eggs that failed to hatch or firstborn chicks that did not survive.[15] The incubation period lasts about a month, and the male tends to his mate whilst she incubates the eggs.[5] The chicks leave the nest, or fledge, around 110 days of age,[16] and remain dependent on their parents until six months of age.[5] They are mature and begin breeding at seven years of age.

General traits

Hyacinth macaws are the largest psittacine. They are also very even-tempered and can be calmer than other macaws, being known as "gentle giants".[17] An attending veterinarian must be aware of specific nutritional needs and pharmacologic sensitivities when dealing with them. Possibly due to genetic factors or captive rearing limitations, this species can become neurotic/phobic, which is problematic.[18]

Distribution and habitat

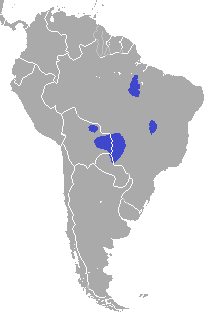

The hyacinth macaw survives today in three main populations in South America: In the Pantanal region of Brazil, and adjacent eastern Bolivia and northeastern Paraguay, in the Cerrado region of the eastern interior of Brazil (Maranhão, Piauí, Bahia, Tocantins, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, and Minas Gerais), and in the relatively open areas associated with the Tocantins River, Xingu River, Tapajós River, and the Marajó island in the eastern Amazon Basin of Brazil. Smaller, fragmented populations may occur in other areas. It prefers palm swamps, woodlands, and other semiopen, wooded habitats. It usually avoids dense, humid forest, and in regions dominated by such habitats, it is generally restricted to the edge or relatively open sections (e.g. along major rivers). In different areas of their range, these parrots are found in savannah grasslands, in dry thorn forest known as caatinga, and in palm stands,[11] particularly the Moriche Palm (Mauritia flexuosa).[19]

The hyacinth macaw has escaped or been deliberately released in to Florida, USA, but there is no evidence that the population is breeding and may only persist due to continuing releases or escapes.[20]

Conservation and threats

The hyacinth macaw is an endangered species due to the cage bird trade and habitat loss.[11] In the 1980s, an estimated 10,000 birds were taken from the wild and at least 50% were destined for the Brazilian market.[21] Throughout the macaw's range, habitat is being lost or altered due to the introduction of cattle ranching and mechanised agriculture, and the development of hydroelectric schemes.[11] Annual grass fires set by farmers can destroy nest trees, and regions previously inhabited by this macaw are now unsuitable also due to agriculture and plantations. Locally, it has been hunted for food, and the Kayapo Indians of Gorotire in south-central Brazil use its feathers to make headdresses and other ornaments. While overall greatly reduced in numbers, it remains locally common in the Brazilian Pantanal, where many ranch-owners now protect the macaws on their land.[22]

The hyacinth macaw is protected by law in Brazil and Bolivia,[11] and commercial export is banned by its listing on Appendix I of the CITES.[23] A number of long-term studies and conservation initiatives are in place; the Hyacinth Macaw Project in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul has carried out important research by ringing individual birds, and has created a number of artificial nests to compensate for the small number of sites available in the region.[5]

The Minnesota Zoo with BioBrasil and the World Wildlife Fund are involved in hyacinth macaw conservation.[14][24]

Causes of endangerment

Parrots as a whole, being of the family Psittacidae, are some of the most threatened birds in the world. This family has the most endangered species of all bird families, especially in the neotropics, the natural home of the hyacinth macaw, where 46 of 145 species are at a serious risk of global extinction.[25] This species qualifies as 'Vulnerable' on the IUCN Red List because the population has suffered rapid reductions with the remaining threats of illegal trapping for the cage bird trade and habitat loss [26] A few serious threats to the survival of the species in the Pantanal include human activities, mainly those resulting in habitat loss, the burning of land for pasture maintenance, and illegal trapping [27] The exceptionally noisy, fearless, curious, sedentary, and predictable nature of this species, along with its specialization to only one or two species of palm in each part of its range, makes them especially vulnerable to capture, shooting, and habitat destruction.[28] Eggs are also regularly preyed on by corvids, opossums, and coatis.[29] Adults have no known natural predators.[4] The young are parasitized by larvae of flies of the genus Philornis.[16]

Although the species has a low genetic variability, it does not necessarily pose a threat to their survival. This genetic structure accentuates the need for protection of hyacinth macaws from different regions to maintain their genetic diversity. Nevertheless, the most important factors negatively affecting the wild population prove to be habitat destruction and nest poaching.[30]

In the Pantanal, habitat loss is largely contributed to the creations of pastures for cattle, while in many other regions, it is the result of clearing land for colonization.[31] Similarly, large areas of habitat in Amazonia have been lost for cattle ranching and hydroelectric power schemes on the Tocantins and Xingu Rivers. Many young manduvi trees are then being grazed on by cattle or burnt by fire, and the Gerias is speedily being converted to land for mechanized agriculture, cattle ranching, and exotic tree plantations.[1] Annual grass fires set by farmers destroy a number of nest trees, and the rise of agriculture and plantations has made habitats formerly populated by the macaws unsuitable to maintain their livelihoods.[26] Moreover, increase in commercial demand for feather art by the Kayapo Indians threatens the species, as up to 10 macaws are needed to make a single headdress.[28]

In the event of the macaws being taken from their natural environment, a variety of factors alter their health such as inadequate hygiene conditions, feeding, and overpopulation during the illegal practice of pet trade. Once birds are captured and brought into captivity, their mortality rates can become very high.[31] Records reveal a Paraguayan dealer receiving 300 unfeathered young in 1972, with all but three not surviving. Due to the poor survival rates of the young, poachers concentrate more heavily on adult birds, which depletes the population at a rapid pace.[28]

According to Article 111 of Bolivian Environmental Law #1333, all persons involved in the trade, capture, and transportation without authorization of wild animals will suffer a two-year prison sentence, along with a fine equivalent to 100% of the value of the animal.[32] While many trackers have been arrested, the illegal pet trade still largely continues in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Unfortunately, animal trafficking is not necessarily viewed as a priority in the city, leaving national departmental and municipal governments unwilling to halt the trade in city centers, and local police reluctant to get involved. This ideology has in turn resulted in a lack of enforcement regarding trade in both CITES-restricted species and threatened species, with little to no restrictions regarding humane treatment of the animals, disease control, or proper hygiene. In the trade centers, the hyacinth macaw demanded the highest price of US$1,000, proving it to be a very desirable and valued bird in the pet trade industry.[33]

Conservation steps taken to preserve the hyacinth macaw

In 1989, the European Endangered Species Programme for the hyacinth macaw was founded as a result of concerns about the status of the wild population and the lack of successful breeding in captivity.[32] Breeding in captivity still remains difficult, being that hand-reared hyacinth macaw offspring have demonstrated to have higher mortality rates, especially within the first month of life. Additionally, they have a higher incidence of acute crop stasis than other macaw species due, in part, to their specific dietary requirements.[34] The hyacinth macaw is protected by law in Brazil and Bolivia, and international trade is prohibited by its listing on Appendix I of the CITES.[26] Appendix I has banned exporting the bird in all countries of origin, and several studies and conservational initiatives have been taken.[1] The Hyacinth Macaw Project in the Caiman Ecological Refuge, located in the Pantanal, has employed artificial nests and chick management techniques, along with effectively raising awareness among cattle ranchers. Many ranch owners in the Pantanal and Gerais, to protect the birds, no longer allow trappers on their properties.[1]

A number of conservation actions have been proposed, including the study of the current range, population status, and extent of trading in different parts of its range. Additionally, propositions have been made to assess the effectiveness of artificial nest boxes, enforce legal measures preventing trade, and experiment with ecotourism at one or two sites to encourage donors.[1] Furthermore, the Hyacinth Macaw Project in Mato Grosso do Sul has carried out important research by ringing individual birds and has created a number of artificial nests to compensate for the small number of sites available in the region.[26] Furthermore, proposals to list the species as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act have been made to further protective measures in the US and to create Bolivian and Paraguayan trade management authorities under presidential control.[28]

Long-term prospects

Each of the three main populations should be managed as a separate biological entity so as to avoid numbers dropping below 500. While the birds may be in decline in the wild, notably higher populations of captive macaws are being held in zoos and private collections. If success in managing and replanting the macaw's food trees and erecting nest boxes as an experiment in the Pantanals is seen, the species could survive. Survival rates could also be enhanced if ranch owners would leave all large and potential nest trees standing and eliminate all trapping on their properties. Ultimately, should these factors work in tandem with erection of nest boxes, fencing off of certain saplings, and the planting of others, the long-term prospects of the hyacinth macaw species would be greatly improved.[28]

Gallery

_2.jpg)

Pet hyacinth macaw on arm

Pet hyacinth macaw on arm

See also

References

- BirdLife International. (2016) Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22685516A93077457.en

- Latham, John (1790). Index Ornithologicus, Sive Systema Ornithologiae: Complectens Avium Divisionem in Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Ipsarumque Varietates (Volume 1) (in Latin). London: Leigh & Sotheby. p. 84.

- Forshaw (2006). plate 70.

- Hagan, E. (2004). Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus. Animal Diversity Web

- "Hyacinth Macaw". WWF. Archived from the original on 4 November 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- "Macaw Psittacidae". National Geographic. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- "The Real Macaw Endangered Tropical Jewels". Public Broadcasting Service. 26 February 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Bates, Henry Walter (1863). The naturalist on the River Amazons, Volume 1. 1. London: John Murray. p. 133.

- Darwin, Charles (1863). "An Appreciation: The Naturalist on the River Amazons by Henry Walter Bates". Natural History Review, vol iii. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- Borsari, Andressa; Ottoni, Eduardo B. (2004). "Preliminary observations of tool use in captive hyacinth macaws (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)". Animal Cognition. 8 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1007/s10071-004-0221-3. PMID 15248094.

- "Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus): BirdLife species factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 19 September 2013. – via ARKive

- Pizo, Marco A.; Donatti, Camila I.; Guedes, Neiva R.; Galetti, Mauro (2008). "Conservation Puzzle: Endangered Hyacinth Macaw Depends on Its Nest Predator for Reproduction" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 141 (3): 792–96. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.12.023. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Hyacinth Macaw Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus". Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Brouwer, Meindert (21 April 2004). "The hyacinth macaw makes a comeback". WWF. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Kuniy, A. (2006). "Handling technique to increase the hyacinth macaw population (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) (Lalham, 1720) – Report of an experience in Pantanal, Brazil". Brazilian Journal of Biology. 66 (1B): 381–82. doi:10.1590/S1519-69842006000200021. PMID 16710531.

- Allgayer, M. C.; Guedes, N. M. R.; Chiminazzo, C.; Cziulik, M.; Weimer, T. A. (2009). "Clinical Pathology and Parasitologic Evaluation of Free Living Nestlings of the Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 45 (4): 972–81. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-45.4.972. PMID 19901373.

- Kalhagen, Alyson. "Hyacinth Macaws". Pet Birds. About.com. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Lennox, Angela. "The companion bird" (PDF). Clinical Avian Medicine, Volume 1. p. 35.

- Forshaw (2006). page 95.

- http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/nonnatives/birds/hyacinth-macaw/

- "Hyacinth Macaw Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus". birdlife.org. 1990. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)". arkive.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "The CITES Appendices". CITES. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- "BioBrasil and the Minnesota Zoo working to save Hyacinth Macaws". Minnesota Zoo. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Wright, Timothy F.; Toft, Catherine A.; Enkerlin-Hoeflich, Ernesto; Gonzalez-Elizondo, Jaime; Albornoz, Mariana; Rodríguez-Ferraro, Adriana; Rojas-Suárez, Franklin; Sanz, Virginia; Trujillo, Ana; Biessinger, Steven R.; Berovidas A., Vincente (June 2001). "Nest Poaching in Neotropical Parrots" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 15 (3): 710–720. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.015003710.x.

- Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus: Hyacinth Macaw. 2013. Encyclopedia of Life.

- Pinho, J. B. & Nogueira, Flavia M. B. (2003). "Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) reproduction in the northern Pantanal, Mato Grosso, Brazil". Ornitologia Neotropical. 14: 29–38.

- Collar, N. J. & Juniper, A. T. Dimensions and Causes of the Parrot Conservation Crisis (PDF). International Council for Bird Preservation. pp. 1–6, 9, 12–15, 19.

- Predator of the world's largest macaw key to its survival Archived 4 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. news.mongabay.com (2008-03-13)

- Faria, Patrícia J.; Guedes, Neiva M. R.; Yamashita, Carlos; Martuscelli, Paulo; Miyaki, Cristina Y. (2008). "Genetic variation and population structure of the endangered Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus): implications for conservation". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17 (4): 765. doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9312-1.

- Tania F. R; Glaucia H. F. R.; Nevia M. R. G.; Aramis A. G. (2006). "Chlamydophila psittaci in free-living Blue-fronted Amazon parrots (Amazona aestiva) and Hyacinth macaws (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil". Veterinary Microbiology. 117 (2–4): 235–41. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.025. PMID 16893616.

- Lücker, H. & Patzwahl, S. (2000). "The European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) for the Hyacinth macaw Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus from 1989 to 1998". International Zoo Yearbook. 37: 178–183. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2000.tb00720.x.

- Mauricio, H. & Hennessey, B. (2007). "Quantifying the illegal parrot trade in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, with emphasis on threatened species". Bird Conservation International. 17 (4): 295–300. doi:10.1017/S0959270907000858.

- Casares, M.; F. Enders (1998). "Experiences in the hand-rearing of hyacinth macaws (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) in Loro Parque". Zoologische Garten. 68: 65–74.

- Forshaw, Joseph M. (2006). Parrots of the World; an Identification Guide. Illustrated by Frank Knight. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09251-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus |

- Hyacinth macaw on the Internet Bird Collection

- Hyacinth macaw media from ARKive

- The Blue Macaws website

- In-Depth Blue Macaw Research

- Audio File of the hyacinth macaw