Hurricane Lenny

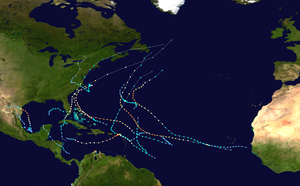

Hurricane Lenny is the second-strongest November Atlantic hurricane on record, behind the 1932 Cuba hurricane. It was the twelfth tropical storm, eighth hurricane, and record-breaking fifth Category 4 hurricane in the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season. Lenny formed on November 13 in the western Caribbean Sea and maintained an unprecedented west-to-east track for its entire duration, which made it earn the nickname, "Wrong Way Lenny". It attained hurricane status south of Jamaica on November 15 and passed south of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico over the next few days. Lenny rapidly intensified over the northeastern Caribbean on November 17, attaining peak winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) about 21 mi (34 km) south of Saint Croix in the United States Virgin Islands. It gradually weakened while moving through the Leeward Islands, eventually dissipating on November 23 over the open Atlantic Ocean.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

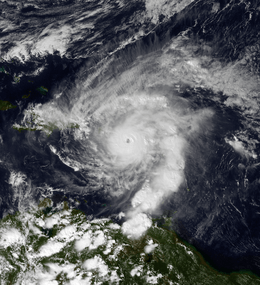

Hurricane Lenny at peak intensity to the south of Saint Croix on November 17 | |

| Formed | November 13, 1999 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 23, 1999 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 933 mbar (hPa); 27.55 inHg |

| Fatalities | 17 direct |

| Damage | $785.8 million (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | Colombia, Puerto Rico, Leeward Islands |

| Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Before moving through the Lesser Antilles, Lenny produced rough surf that killed two people in northern Colombia. Strong winds and rainfall resulted in heavy crop damage in southeastern Puerto Rico. Despite the hurricane's passage near Saint Croix at peak intensity, damage on the small island was only described as "moderate", although there was widespread flooding and erosion. Damage in the United States territories totaled about $330 million. The highest precipitation total was 34.12 in (867 mm) at the police station on the French side of Saint Martin. On the island, the hurricane killed three people and destroyed more than 200 properties. In nearby Antigua and Barbuda, the hurricane killed one person; torrential rainfall there contaminated the local water supply. Significant storm damage occurred as far south as Grenada, where high surf isolated towns from the capital city.

Meteorological history

Hurricane Lenny began as a low-pressure area that was first observed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on November 8. It developed an area of convection but remained poorly defined for the next few days. Thunderstorms spread across the region, producing heavy rainfall in portions of Mexico and Central America. On November 13, the system became better organized; a Hurricane Hunters flight later that day discovered a surface circulation and winds of about 35 mph (56 km/h). The data indicated the development of Tropical Depression Sixteen at 1800 UTC, about 175 mi (282 km) south of the Cayman Islands.[1] The depression's convection was fairly disorganized, and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) did not anticipate any strengthening for three days.[2] For much of its existence, the tropical cyclone maintained a track from west to east across the Caribbean Sea, which was unprecedented in the Atlantic hurricane database, earning it the nicknames "Left-Hand Lenny" and "Wrong Way Lenny". The path resulted from its movement along the southern end of a trough over the western Atlantic Ocean.[1]

After its formation, the depression gradually became better organized;[3] the NHC upgraded it to Tropical Storm Lenny on November 14,[1] based on reports from the Hurricane Hunters. When it was first upgraded to a tropical storm, the cyclone already had winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a developing eye feature.[4] At 0000 UTC on November 15, Lenny attained hurricane status about 175 mi (282 km) southwest of Kingston, Jamaica.[1] The quick intensification was unexpected and occurred after a large area of convection blossomed over the center. At the same time, Lenny developed an anticyclone aloft, which provided favorable conditions for the hurricane's development.[5] After moving east-southeastward during its initial development stages, the hurricane turned more to the east on November 15. The Hurricane Hunters reported winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), which indicated that Lenny had become a Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale.[6] However, the cloud pattern subsequently became less organized as the eye disappeared, and Lenny's winds weakened to 85 mph (137 km/h) while the hurricane passed south of Hispaniola.[1] The NHC noted the deterioration could have been due to a disruption of the storm's small inner core by "subtle environmental changes". After the sudden weakening,[7] the Hurricane Hunters reported that the eye had reformed and the hurricane's winds had reached 100 mph (160 km/h). At the time, a ridge was expected to build to Lenny's east and turn the storm northeastward into Puerto Rico 24 hours later.[8]

Beginning on November 16, Hurricane Lenny underwent a 24-hour period of rapid deepening, reaching major hurricane status about 165 mi (266 km) south of the Mona Passage.[1] It developed well-defined banding features, good outflow, and a circular eye that was visible from the radar in San Juan, Puerto Rico.[9] The hurricane continued to become better organized, with an eye 29 mi (47 km) in diameter surrounded by a closed eyewall.[10] Around 1200 UTC on November 17, Lenny intensified into a Category 4 hurricane while approaching the islands of the northeastern Caribbean. It was the fifth storm of such intensity in the year, setting the record for most Category 4 hurricanes in a season.[1] The hurricane then made its closest approach to Puerto Rico, passing about 75 mi (121 km) southeast of Maunabo.[11] Shortly thereafter, Lenny attained peak winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) while passing 21 mi (34 km) south of the island of Saint Croix in the United States Virgin Islands.[1] This made it the second-strongest hurricane on record to form during the month of November.[12] Hurricane Hunters reported Lenny's peak winds in the southeastern portion of the hurricane; the group also reported a minimum pressure of 933 mbar, a drop of 34 mbar in 24 hours. In addition, a dropsonde recorded winds of 210 mph (340 km/h) while descending to the surface, the highest dropsonde wind speed recording in a hurricane at the time.[1]

Around the time it peaked in intensity, Lenny's forward speed decreased in response to light steering currents between two ridges. Despite favorable conditions for strengthening, the hurricane weakened as it turned to an eastward drift, possibly due to the upwelling of cooler waters. Late on November 18, Lenny's eye moved over Saint Martin with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h). After continued weakening, the hurricane struck Anguilla and Saint Barthélemy the next day. It turned southeastward while still drifting, bringing heavy rainfall and strong winds to the islands across the northeastern Caribbean.[1] Late on November 19, Lenny weakened to tropical storm intensity after increased wind shear exposed the cyclone's center from the deepest convection.[1][13] Early on November 20, the storm made landfall on Anguilla,[1] although by then the center had become difficult to locate.[14] Later that day, the cyclone exited the Caribbean,[15] continuing its southeast track. On November 21, Lenny turned to the northeast and weakened to a tropical depression.[1] The deep convection was located at least 100 mi (160 km) east of the increasingly elongated center.[16] Lenny turned to the east for the final time early on November 22, dissipating on the next day about 690 mi (1,110 km) east of the Lesser Antilles.[1]

Preparations

Early in Lenny's existence, a tropical storm warning and hurricane watch were issued for Jamaica. Later, a hurricane watch was issued for the southern coast of Hispaniola, and a tropical storm warning was also issued for the Dominican Republic.[1] Haitian officials declared a state of alert in three southern provinces and allocated about $1 million (1999 USD) in hurricane funds.[17] Residents in flood-prone areas were advised to evacuate in southern Haiti and in the neighboring Dominican Republic.[18][19]

A hurricane watch was issued for Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands late on November 15, which was upgraded to a hurricane warning six hours later.[1] By that time, Lenny was projected to move over Puerto Rico.[8] After Lenny made its closest approach to the island, the hurricane warning was downgraded to a tropical storm warning on November 17, which was discontinued the following day along with the advisories in the Virgin Islands.[1] In Puerto Rico, the media maintained continuous coverage on the hurricane based on statements and warnings from the San Juan National Weather Service office. Based on the coverage, the public was well informed of the hurricane's threat to the island. Before the storm and as a result of its impact, around 4,700 people evacuated to 191 shelters. This included 1,190 residents in Ponce who evacuated to 27 schools, as well as 584 people in western Puerto Rico.[20] Officials closed all schools, banned the sale of alcohol, and ordered a freeze on the price of emergency supplies.[21] The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated six medical assistance teams, three medical support teams, and two advance medical assessment units. The agency stored five days' worth of food in schools in the U.S. Virgin Islands.[22] Before the hurricane's arrival, U.S. Virgin Islands governor Charles Wesley Turnbull declared a state of emergency.[23] In St. Croix, 309 people rode out the storm in shelters.[11] Officials opened eight shelters in the British Virgin Islands.[20] There, airlines and hotels assisted in evacuating tourists from the area.[24]

Governments across the eastern Caribbean issued hurricane warnings as far south as Montserrat.[1] In Anguilla, residents near the coast were advised to evacuate. Schools closed ahead of the storm, and the ferry between the island and Saint Martin was halted and moved to a safe location. In Saint Kitts and Nevis, the National Emergency Management Agency was activated on November 16. Officials there advised residents living near ghauts to evacuate, and one shelter was located in each district of the country. In addition, stores were open for longer hours to allow people to stock up on supplies.[25] Most businesses and schools were closed in Antigua and Barbuda during the storm, while in Dominica, the airport was closed.[26] Further south, there was little warning for the hurricane in Grenada, and most people left their boats in the water.[27]

Impact

| County/Region | Deaths | Damage | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 2 | unknown | |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1 | $51.3 million | |

| Guadeloupe | 5 | $100 million | |

| Dominica | 0 | $21.5 million | |

| Montserrat | 0 | unknown | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 0 | $41.4 million | |

| Saint Martin | 3 | $69 million | [28] |

| Martinique | 1 | unknown | |

| Saint Lucia | 0 | $6.6 million | [28] |

| Puerto Rico | 0 | $105 million | |

| U.S Virgin Islands | 0 | $225 million | |

| British Virgin Islands | 0 | $5.6 million | |

| Others | 5 | ||

| Total | 17 | ~$785.8 million |

Across the eastern Caribbean, Hurricane Lenny damaged vital infrastructure, including roads and piers in the tourism-dependent islands. Most of the islands' tourism areas were on western-facing beaches, many of which were unprepared for the high waves and winds produced by Lenny.[29]

Central Caribbean

Early in its existence, Lenny produced large waves and high tides along the Guajira Peninsula in Colombia,[1] sinking two boats and flooding 1,200 houses. There were also reports of flooded businesses and damaged crops. In the country, strong winds on the storm's fringe killed a man by striking him with a beam. Although there were initial reports of nine people missing,[17] only two were counted in the death toll for mainland Colombia.[1] Two sailors were killed offshore when their yacht was lost in the southern Caribbean Sea.[1]

Along the ABC Islands off the north coast of Venezuela, the hurricane produced 10-to-20 ft (3-to-6 m) waves along the southwest coastlines.[30] The waves caused heavy beach erosion and coastal damage to properties and boats.[31]

In Jamaica, the hurricane dropped heavy rainfall but left little damage. Rains in the Dominican Republic caused flooding in the country's southwest portion.[19] Flooding around Les Cayes in southwestern Haiti destroyed 60 percent of the rice, corn, and banana plantations, while high waves wrecked several houses in Cavaellon.[21]

Hurricane Lenny was originally forecast to strike Puerto Rico, although it remained south of the island.[1] Beginning on November 17, Lenny affected Puerto Rico with gusty winds and heavy rainfall. Rainfall in the days prior to Lenny's approach left areas susceptible to flooding, which caused many rivers in the northeastern portion of the island to overflow their banks following the storm. Such flooding forced towns to evacuate along the rivers, and also resulted in the closure of secondary and primary highways. The heavy rains also caused mudslides and rockslides.[11] The peak rainfall on the island was 14.64 in (372 mm) in Jayuya in central Puerto Rico.[32] Tides in San Juan were about 1.8 ft (0.55 m) above normal. There, high seas washed a 546 ft (166 m) freighter ashore. Winds in the Puerto Rican mainland were not significant, gusting to 48 mph (77 km/h) in Ceiba. The storm left 22,000 people without power and 103,000 people without water.[11] Because of the heavy rainfall, about 200 farmers in southeastern Puerto Rico sustained about $19 million in crop damage (1999 USD). In the affected region, the heavy rainfall destroyed 80 percent of the vegetables and 50 percent of the plantains. Damage throughout the island totaled $105 million (1999 USD).[33]

Virgin Islands

After passing southeast of Puerto Rico, Hurricane Lenny struck St. Croix in the United States Virgin Islands, although its strongest winds remained southeast of the island. There, gusts reached 112 mph (180 km/h), while sustained winds officially peaked around 70 mph (110 km/h). Strong winds damaged the roofs of many houses in eastern St. Croix[1] and knocked down trees and power lines. The winds left severe damage to vegetation after fruits and vegetables were blown away. Rainfall peaked at 10.47 in (266 mm),[32] which caused widespread flooding of many properties in the island's western portion. In Frederiksted, the hurricane produced a storm surge of 15–20 ft (4.6–6.1 m)[1] along with high waves that washed out roads and damaged coastal structures. There was also severe beach erosion in western St. Croix; high waves dumped 6.5 ft (2.0 m) of sand onto coastal roads about 100 ft (30 m) inland,[11] and also washed several boats ashore.[1] The National Weather Service described the damage as "moderate".[11]

Elsewhere in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Lenny produced a storm surge of about 1.8 ft (0.55 m) in St. Thomas.[1] Sustained winds on the island reached 53 mph (85 km/h) at the Cyril E. King Airport, with gusts to 70 mph (110 km/h). On nearby St. John, wind gusts reached 92 mph (148 km/h),[11] and sustained hurricane-force winds of 83 mph (134 km/h) were reported on Maria Hill.[1] Rains were not as heavy as on St. Croix; the maximum amounts were 4.34 in (110 mm) on St. Thomas and 2.95 in (75 mm) on St. John. Both islands reported beach erosion along their southern coastlines.[11] Damage on St. Thomas was minimal, limited to minor flooding and mudslides. The Virgin Islands National Park in St. John reported over $1.6 million in damage (1999 USD).[33] In Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, the hurricane left about $330 million in damage (1999 USD), but caused no deaths.[1]

In Virgin Gorda in the nearby British Virgin Islands, the hurricane produced sustained winds of 55 mph (89 km/h), with gusts to 85 mph (137 km/h). Rainfall amounted to around 4 in (100 mm)[1] and caused a mudslide near Coxheath. High waves eroded a portion of Sir Francis Drake Highway, and the high winds destroyed the roof of an apartment.[20] Property damage in the British Virgin Islands totaled $5.6 million (1999 USD); however, the damage combined with the loss of tourism and productivity yielded a loss of $22 million to the islands' economy, or 3.1 percent of the gross domestic product.[34]

Northern Leeward Islands

Anguilla

The eye of Lenny moved over Anguilla, an island located east of the British Virgin Islands.[1] Localized flooding was reported,[35] including in the capital, The Valley, where waters reportedly reached a depth of 14 ft (4.3 m).[36] The hurricane struck only a month after Hurricane Jose had affected the region, causing significant beach erosion along Anguilla's coastline.[37] Damage from Lenny amounted to $65.8 million.[38]

Saint Barthélémy and Saint Martin

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 700.0 | 27.56 | Lenny 1999 | Meteorological Office, Phillpsburg | [39] |

| 2 | 280.2 | 11.03 | Jose 1999 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [40] |

| 3 | 165.1 | 6.50 | Luis 1995 | [41] | |

| 4 | 111.7 | 4.40 | Otto 2010 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [42] |

| 5 | 92.3 | 3.63 | Rafael 2012 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [43] |

| 6 | 7.9 | 0.31 | Ernesto 2012 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [43] |

| 7 | 7.0 | 0.28 | Chantal 2013 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [44] |

| 8 | 6.6 | 0.26 | Dorian 2013 | Princess Juliana International Airport | [44] |

On Saint Barthélemy, the hurricane produced record-breaking precipitation of around 15 in (380 mm). Waves reached 16 ft (4.9 m) on the island's western portion.[1] The highest precipitation related to the storm occurred at the police station on the French side of Saint Martin, where a total of 34.12 in (867 mm) was recorded.[32] This included a record 24-hour total of 18.98 in (482 mm). Total damage was extensive but not as extreme or catastrophic as Hurricane Luis in 1995.

The Dutch Antilles

The SSS Islands, which include Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten, were in the path of Hurricane Lenny on November 18 through 19.[1] On Saba, there was an unofficial wind gust of 167 mph (269 km/h) before the instrument blew away. The island sustained damage to several buildings, including airport facilities.[1] On the Dutch side of the island of Saint Martin, rainfall peaked at 27.56 in (700 mm) in Philipsburg.[1] The rains resulted in mudslides and flooding and were the primary form of impact on the island. For 36 hours, the island experienced tropical storm conditions, and there were three times when the winds surpassed hurricane force. Sustained winds on the island peaked at 84 mph (135 km/h) at the Princess Juliana International Airport;[31] these were the highest sustained winds observed on land.[1] The airport also reported a wind gust of 104 mph (167 km/h).[31] As a result, the three SSS Islands sustained power and telephone outages.[45] There was widespread destruction of the roofs of houses across the island,[46] and over 200 houses were destroyed.[47] Damage was estimated at $69 million,[46] and there were three deaths on the Dutch side of St. Martin.[31] Two of these deaths were from flying debris, and the other was due to a collapsed roadway.[1]

Due to the hurricane's unusual track from the west, it produced unparalleled waves of 10–16 ft (3.0–4.9 m) along the western coast of St. Martin,[31] which damaged or destroyed many boats.[1] During its passage, Lenny left widespread damage to the infrastructure, including to the airport, harbor, resorts, power utilities, schools, and hospitals.[46]

Antigua and Barbuda

While passing over Antigua, Hurricane Lenny dropped 18.32 in (465 mm) of rain at the V. C. Bird International Airport, while locations in the southern portion recorded over 25 in (640 mm).[1] The rainfall caused severe flooding in Antigua, resulting in landslides in the northwestern and southern portion of the island.[29] Flooding washed out major roadways, including one bridge.[48] Along the coast, the storm caused severe beach erosion. About 65 percent of Barbuda experienced flooding due to the rainfall and the island's flat topography. The flooding contaminated the water storage facilities and all private wells.[29] About 95 percent of the crops in Barbuda were destroyed.[49] Damage in the country of Antigua and Barbuda totaled $51.3 million,[29] and there was one death.[50]

Saint Kitts, Nevis and Montserrat

The hurricane's waves reached 20 ft (6.1 m) along the coasts of Saint Kitts and Nevis, washing up to 600 ft (180 m) inland. Several businesses were flooded, and some beach erosion was reported.[35] The hurricane destroyed 46 homes and damaged 332 others to varying degree.[50] Home damage forced four families to evacuate.[35] Heavy rains caused mudslides on Saint Kitts,[1] and heavy damage occurred in Old Road Town.[51] Damage in the country amounted to $41.4 million.[48] In Montserrat, damage was reported along its western coastline.[35] After high waves capsized a boat, a crew of three required rescue.[52]

Guadeloupe

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 582 | 22.91 | Luis 1995 | Dent de l'est (Soufrière) | |

| 2 | 508 | 20.00 | Marilyn 1995 | Saint-Claude | [53] |

| 3 | 466 | 18.35 | Lenny 1999 | Gendarmerie | [54] |

| 4 | 389 | 15.31 | Hugo 1989 | ||

| 5 | 318 | 12.52 | Hortense 1996 | Maison du Volcan | [55] |

| 6 | 300 | 11.81 | Jeanne 2004 | [56] | |

| 7 | 223.3 | 8.79 | Cleo 1964 | Deshaies | [53] |

| 8 | 200 | 7.87 | Erika 2009 | [57] | |

| 9 | 165.3 | 6.51 | Earl 2010 | Sainte-Rose (Viard) | [58] |

| 10 | 53.6 | 2.11 | Edith 1963 | Basse Terre | [53] |

Guadeloupe received record precipitation amounts in some areas, generally ranging from 6 to 19 inches (150 to 480 mm). On Basse-Terre, the western island of Guadeloupe, the hurricane produced a significant wave height of 9.8 ft (3.0 m), with estimates as high as 13 ft (4.0 m). There were five deaths, especially from drowning and electrocution in Guadeloupe and damage in the island totaled at least $100 million.[1]

Although there were no tropical-storm sustained wind recorded as the storm didn't really impacted the islands unlike previous hurricanes such as Luis, Marilyn and Georges, the extent of damage was globally heavier due to the unusual high waves in the western portion of the island and the very slow-moving storm that generated unrelated flooding inland in Grande-Terre for a 48 hour-period.

Dominica

In Dominica, high waves damaged the island's western coastal highway, leaving the most heavily traveled road temporarily closed.[29] Road closures cut off links between towns on the island.[35] The hurricane destroyed at least 50 homes,[59] including 3 that were washed away by the waves.[26] Hotels along the island's west coast sustained heavy damage, and across the nation the hurricane's impact was worse than that from Hurricane Luis four years prior.[59] Damage on the island totaled $21.5 million.[29]

Windward Islands

Rainfall of around 3 in (76 mm) reached as far south as Martinique, where one person was killed.[32] Further south, high waves in Saint Lucia washed away beaches, a seawall, and coastal walkways.[29] At least 40 houses were damaged along the coast, which left several families homeless.[45] Damage in the country totaled $6.6 million.[29] In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the hurricane washed away four buildings and damaged five others.[35] About 50 people were left homeless in the country.[47]

In western Grenada, high waves affected much of the coastline,[29] destroying 21 small boats and causing significant beach erosion.[1][29] The waves covered the entire Grand Anse Beach in Saint George Parish. The erosion heavily impacted tourist areas and also threatened the foundation of the runway at the Maurice Bishop International Airport. Storm damage cut off the towns in western Grenada from the capital city of Saint George's. The cut-off roads resulted in an island-wide fuel shortage.[29] In Saint John Parish, the storm knocked out the water and power supply and forced several families to evacuate their damaged houses.[59] The small island Carriacou, located north of Grenada, sustained damage to the road to its primary airport.[29] At least 10 homes were destroyed in the country,[1] and damage totaled $94.6 million; this represented 27 percent of the island's gross domestic product.[29] Effects from the storm reached as far south as Trinidad and Tobago.[29] In the country, storm surge caused damage to boats and coastal structures, while beach erosion was reported in Tobago.[60]

Aftermath

Following heavy damage to the coral reef around Curaçao, workers placed reef balls to assist in replenishing the damaged structure.[61] In Puerto Rico, workers quickly responded to power and water outages. Similarly on Saint Croix, power systems were quickly restored.[62] On November 23, U.S. President Bill Clinton declared the U.S. Virgin Islands a disaster area. This allocated federal funding for loans to public and private entities and provided 75 percent of the cost of debris removal.[63] By December 10, nearly 3,000 residents had applied for assistance, mostly on St. Croix. In response, the federal government provided about $480,000 to the affected people.[64] The United States Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance provided $185,000, mostly directed toward the United Nations Development Programme, for aid to other islands in the eastern Caribbean. Other agencies, including the Caribbean Development Bank, the United Kingdom's Department for International Development, and the European Union, provided $1.1 million in assistance.[29]

In response to the damage on Saint Martin, officials in the Netherlands Antilles issued an appeal to the European Parliament for assistance from the international community.[46] Due to their small population and area, the small islands of the eastern Caribbean required international funding to repair the damage from the hurricane and return to normal. In Antigua and Barbuda, officials worked quickly to repair roads and clean Barbuda's water system.[29] However, 20,000 people in Antigua remained without water for a week after the hurricane, and the stagnant water caused an increase in mosquitoes.[48] The government of Dominica provided 42 families with temporary shelters. With a loan from the Caribbean Development Bank, the government worked to complete a sea wall along a highway south of its capital Roseau. The Saint Lucian government provided housing to 70 families. In Grenada, workers repaired the road system to allow fuel transportation across the island and began to reclaim land near its airport to mitigate erosion.[29] Regions in Antigua and Grenada were declared disaster areas.[50][65] Across the eastern Caribbean, local Red Cross offices provided food and shelter to affected citizens.[59] High damage to tourist areas caused a decrease in cruise lines. A damaged hotel in Nevis left 800 people unemployed due to its closure.[66]

Due to its effects, the name Lenny was retired by the World Meteorological Organization and will never again be used for an Atlantic hurricane.[67] The name was replaced with Lee in the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season.[68]

See also

Notes

- John L. Guiney (1999-12-09). Hurricane Lenny Preliminary Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- Miles B. Lawrence (1999-11-13). Tropical Depression Sixteen Discussion One (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- Richard Pasch (1999-11-14). Tropical Depression Sixteen Discussion Two (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- Miles B. Lawrence (1999-11-14). Tropical Storm Lenny Special Discussion Five (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- Richard Pasch (1999-11-15). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Seven (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- Jack Beven (1999-11-15). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Eight (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- Richard Pasch (1999-11-16). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Eleven (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-24.

- Jack Beven (1999-11-16). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Twelve (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- Lixion Avila (1999-11-16). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Fourteen (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Richard Pasch (1999-11-16). Hurricane Lenny Discussion Fifteen (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Preliminary Storm Report on Hurricane Lenny November 16–19 1999 (Report). San Juan, Puerto Rico National Weather Service Office. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- Michael Brennan (2009-01-26). Hurricane Paloma Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- Lixion Avila (1999-11-19). Tropical Storm Lenny Discussion Twenty-Six (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- Miles B. Lawrence (1999-11-20). Tropical Storm Lenny Discussion Twenty-Seven (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- James Franklin (1999-11-20). Tropical Storm Lenny Discussion Twenty-Eight (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- James Franklin (1999-11-21). Tropical Depression Lenny Discussion Thirty-Two (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- "One death blamed on Hurricane Lenny; still threatens Caribbean". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 1999-11-16. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "Hurricane Lenny Gains Strength, Threatens Islands". Observer-Reporter. Associated Press. 1999-11-16. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- Michael Norton (1999-11-14). "Late hurricane threatens Haiti, Puerto Rico". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- "NEAC Chairman Looks at Impact of Recent Hurricanes on the BVI". Island Sun. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- "Hurricane Lenny threatens Puerto Rico". BBC. 1999-11-17. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (1999-11-17). "FEMA Mobilizes in Response to Hurricane Lenny". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Cynthia Long (1999-11-17). "Hurricane Lenny heads for Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands". DisasterRelief.org. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1999-11-16). "CDERA Situation Report # 2 - Hurricane Lenny". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1999-11-16). "Situation Report # 3 - Hurricane Lenny". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1999-11-18). "Caribbean Hurricane Lenny Alert". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Peter Coles (2003). "The time of sands..." UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- National Hurricane Center (1996). "Hurricane Marilyn Preliminary Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- "Hurricane Lenny Recovery in the Eastern Caribbean" (DOC). USAID. 2000-04-17. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- Anja M. Scheffers (2002). "Paleotsunami Evidences from Boulder Deposits on Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire" (PDF). The International Journal of the Tsunami Society. 20 (1): 32. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- Hurricanes and Tropical Storms in the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba (PDF) (Report). Netherlands Antilles and Aruba Meteorological Service. April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- David Roth (2006-05-04). "Hurricane Lenny - November 14–21, 1999". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections (PDF) (Report). 41. National Climatic Data Center. November 1999. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- Jerinice Stoutt (2005-11-21). "Impact of Hurricanes on the BVI Economy". Government of the British Virgin Islands. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1999-11-18). "Post Impact Report #1 - Hurricane Lenny". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Gillian Cambers (December 1999). "Late Hurricanes: a Message for the Region". UNESCO. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- Wycliffe Richardson (1999-11-18). "Hurricane Lenny Batters St. Croix". Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- "Countries" (PDF). Health in the Americas. 2. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Guiney, John L (December 9, 1999). Preliminary Report: Hurricane Lenny November 13 - 23, 1999 (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Pasch, Richard J; National Hurricane Center (November 22, 1999). Hurricane Jose: October 17 - 25, 1999 (Preliminary Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Lawrence, Miles B; National Hurricane Center (January 8, 1996). Hurricane Luis: August 27 - September 11, 1995 (Preliminary Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Cangialosi, John P; National Hurricane Center (November 17, 2010). Hurricane Otto October 6 - 10 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 6-7. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- Connor, Desiree; Etienne-LeBlanc, Sheryl (January 2013). Climatological Summary 2012 (PDF) (Report). Meteorological Department St. Maarten. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- 2013 Atlantic Hurricane Season Summary Chart (PDF) (Report). Meteorological Department St. Maarten. January 2013. Archived from the original on February 5, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- Carol Bareuther (1999-11-19). "Hurricane Lenny causes havoc in Caribbean". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Resolution on Hurricane Lenny – St Martin – West Indies (Motion for a Resolution). European Parliament. February 22, 2000. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1999-11-18). "Eastern Caribbean: Hurricane Lenny Information Bulletin No. 3". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (1999-11-30). "Hurricane Lenny OCHA Situation Report No. 7". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Gary Padgett. "November 1999 Tropical Summary". Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- US Agency for International Development (1999-11-23). Northeastern Caribbean Hurricane Lenny Fact Sheet #1, FY 2000 (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- "Country Hazard Profiles". Area on Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief. 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Carol Bareuther (1999-11-18). "Hurricane Lenny pounds Caribbean". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Service Régional de METEO-FRANCE en Guadeloupe. COMPTE RENDU METEOROLOGIQUE: Passage de l'Ouragan LENNY du 17 au 19 novembre 1999 sur l'archipel de la Guadeloupe. Retrieved on 2007-02-19. A

- Avila, Lixion A; National Hurricane Center (October 23, 1996). Hurricane Hortense 3-16 September 1996 (Preliminary Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- World Meteorological Organization. Review of the Past Hurricane Season. Retrieved on 2007-02-24.

- (in French) AFP, France Antilles (2009-09-03). "07 - La Tempête tropicale Erika affecte la Guadeloupe". Catastrophes Naturalles. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- "PASSAGE DE L'OURAGAN EARL SUR LA GUADELOUPE Et LES ILES DU NORD" [PASSAGE OF THE HURRICANE EARL ON THE GUADELOUPE AND THE NORTH ISLANDS] (PDF). meteo.fr (in French). Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1999-11-19). "Eastern Caribbean: Hurricane Lenny Information Bulletin No. 2". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Tropical Cyclones Affecting Trinidad and Tobago 1725-2000 (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service via the Internet Wayback Machine. 2002-05-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2005. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- "Toegankelijk vanaf de volgende stranden" (in Dutch). Curacao Actief. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (1999-11-19). "Hurricane Lenny Update". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- "Disaster Aid Ordered for Virgin Islands Hurricane Recovery". Federal Emergency Management Agency. 1999-11-23. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- "Virgin Islanders Receive More Than A Half-Million Dollars In Federal Assistance". Federal Emergency Management Agency. 1999-12-10. Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (1999-11-20). "Post Impact Report #2 - Hurricane Lenny". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (1999-12-03). "Hurricane Lenny OCHA Situation Report No. 8". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Hurricane Center. 2011-03-16. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. 2006-01-06. Archived from the original on 2006-02-09. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Lenny. |