Hurricane Ismael (1983)

Hurricane Ismael was responsible for significant flooding throughout the Inland Empire of the United States in August 1983. The origins of Hurricane Ismael were from a northward bulge of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) in early August, which resulted in the formation of a tropical depression on August 8. Six hours later, it was upgraded into Tropical storm Ismael. Continuing to intensify, Ismael was upgraded into a hurricane late on August 10 and subsequently developed an eye. After bypassing the Revillagigedo Islands, the storm reached its peak wind speed of 100 mph (160 km/h). Late on August 11, Hurricane Ismael began to weaken as it encountered cooler waters. The following day, Ismael was downgraded into a tropical storm. On August 14, the storm was downgraded into a tropical depression approximately 250 mi (400 km) west of Point Ensenada. After turning north, Ismael dissipated later that day near Guadalupe Island.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

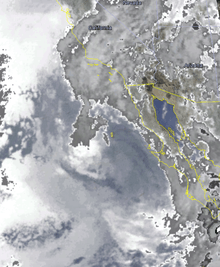

Hurricane Ismael on August 10 | |

| Formed | August 8, 1983 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 14, 1983 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Fatalities | 4 confirmed, 1 presumed |

| Damage | $19 million (1983 USD) |

| Areas affected | Baja California Peninsula, California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona |

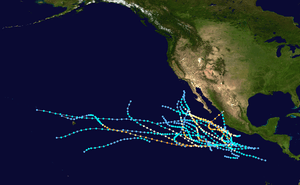

| Part of the 1983 Pacific hurricane season | |

While still out at sea, Ismael brought 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) waves to Southern California, though waves from the storm were less than expected. One person was swept away at a beach. The remnants of the storm later moved over the region, resulting in moderate rainfall. The Yucca Valley was the worst hit by the storm, where nearly every road was washed out. Almost 50,000 residents were isolated due to rains. A tornado was spotted near Los Angeles, causing minor damage. In San Bernardino, many buildings were destroyed. Around 80,000 homes were left without power across the Inland Empire. Moreover, three interstates were closed. In all, minor injuries were reported, three people died in San Bernardino when their car swept into a channel, and an engineer was killed returning to China Lake when her car was swept into a wash. Damage in the region totaled $19 million (1983 USD). After affecting California, the remnants of the hurricane moved into Nevada. Many parking lots in Laughlin were flooded; two small towns in Clark County were also isolated. Furthermore, several major streets along the outskirts of Las Vegas were closed because of flooding.

Meteorological history

Hurricane Ismael originated from a northward bulge of the ITCZ in early August. On August 7, the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center (EPHC) reported that this bulge had resulted in the formation of a tropical disturbance centered 500 mi (800 km) south of Acapulco. Late on August 8, the system was upgraded into a tropical depression.[1] Initially, the storm was expected to turn west and remain at sea;[2] however, the depression turned northwest instead. Six hours after becoming a tropical cyclone, the low was upgraded into Tropical storm Ismael.[1]

After remaining a marginal tropical storm for 18 hours, Ismael began to deepen and by August 10, it was approaching hurricane intensity.[3] By this time, the storm was forecast to accelerate and approach Guadalupe Island in three days.[2] At 1800 UTC on August 10, Ismael was upgraded into a hurricane. At 0245 UTC the next day, an eye began to form as the system passed east of the outer Revillagigedo Islands.[1] Nine hours later, the EPHC upgraded the storm into a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS); simultaneously, the storm reached its peak of 100 mph (160 km/h). At the time of its peak, Hurricane Ismael was located about 400 mi (640 km) west of Cabo San Lucas.[3] Sandwiched between a ridge to the west of the hurricane and a trough off the coast of California, Ismael turned west north-west and accelerated.[1]

Late on August 11, Hurricane Ismael began to weaken as it encountered cooler waters.[1] According to the EPHC, the storm was downgraded to a Category 1 on the SSHWS late on August 11. The following day, Ismael was downgraded into a tropical storm about 380 mi (610 km) west of the Baja California Peninsula.[3] On August 13, Hurricane Hunters flew through the storm, penetrating the center of circulation twice.[1] During its first penetration, the aircraft reported winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) just east of the center and also noted that the weakening system had a poorly defined eye. Two hours later, the aircraft made its second pass through Tropical Storm Ismael, with the aircraft reporting winds of 35 mph (55 km/h). Based on this, the storm was downgraded into a tropical depression while centered about 250 mi (400 km) west of Point Ensenada. After turning north and entering even cooler waters,[1] the storm made landfall on Guadalupe. The depression dissipated later on August 14 about 20 mi (30 km) southwest of Guadalupe Island[3] which is not normally affected by tropical cyclones.[4]

Impact

California

While still out at sea, Ismael brought rough seas that lead to one home on the Capistrano Beach being ruled unsafe.[5][6] Although waves from the storm were less than expected, swells of 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) were estimated along south-facing beaches near Santa Barbara. In Malibu, one home was damaged due to the increased surf.[7] In Laguna Beach, in southern Orange County, a 20-year-old woman was swept off rocks and later died.[8][9] Overall, Hurricane Ismael was one of six tropical cyclones to bring high waves to the state within a span of a month.[10]

On August 11, the outer rainbands of Hurricane Ismael brought unseasonably high humidity and thunderstorms to Southern California.[11] Subsequently, flash flood watches were posted for much of Southern California. The remnants of the storm eventually moved over the area, resulting in significant flooding.[12] Some areas sustained 2 in (50 mm) of rain,[13] leading to water depths of 2 to 4 ft (61 to 122 cm) on roadways.[14] The towns of Joshua Tree, Yucca Valley, Twentynine Palms, California, and Landers were the hardest hit.[14] Nearly every road was washed out in the Yucca Valley.[15]

Almost 50,000 residents in Palm Springs were isolated due to brief, but heavy rains.[14] In addition, a tornado damaged two homes and over seven chimneys near Los Angeles. Heavy rains also drenched the cities of Riverside and San Bernardino while flooding several homes.[14] In the latter, many buildings were destroyed, forcing widespread evacuations.[16] In Rancho Mirage, 24 homes were damaged.[17][18] One woman had to be rescued after she was swept 3 mi (4.8 km) downstream a river in Los Angeles.[19] Around 80,000 homes were left without power across the Inland Empire, though within 24 hours after the outage, power was restored to all but 4,000 residents.[20] Moreover, portions of Interstate 10, 14, and 215 were closed. The highway the lead into Palm Springs was closed as well, resulting in major traffic jams.[17] In all, minor injuries were reported.[16] However, three people died in San Bernardino when their car swept into a channel.[17] Damage from the storm totaled $19 million (1983 USD).[21]

Nevada

Heavy rains that preceded the storm forced thousands of gamblers along the Las Vegas Strip to be evacuated and left two people missing.[22] The remnants of the storm later moved into the region, bringing additional flooding. Many parking lots in the resort town of Laughlin were flooded.[17] Furthermore, the villages of Searchlight and Blue Diamond were isolated due to flooding.[16] Several major streets in Paradise were closed because of flooding and sandbag barriers were erected alongside Caesars Palace to prevent further flood damage.[17] In addition, record river levels were measured along the Amargosa River near Death Valley.[23]

Elsewhere

In the Mexican states of Baja California and Baja California Sur, the storm brought high clouds over the region for several days.[24] In Ensenada, minor flooding was recorded.[25] Along the peninsula, waves up to 8 ft (2.4 m) were measured.[26]

Residents of Davis County, Utah that were in close proximity of streams were put on alert due to the threat of flooding.[27] The remnants of Hurricane Ismael ultimately brought thunderstorms to Arizona and Utah.[28] In Mohave County, up to 3 in (76 mm) of rain was recorded.[17] Further south and west, in Phoenix, a thunderstorm flooded streets and brought down power lines.[29]

See also

- List of Baja California hurricanes

- List of California hurricanes

- Hurricane Darby (1992)

- Hurricane Liza (1968)

- Hurricane Ramon

- Hurricane Marie (2014) ― brought similarly high surf to California, but unlike Ismael, no rain.

References

- Emil B. Gunther; R.L. Cross (July 1984). <1419:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2 "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1983". Monthly Weather Review. 112 (7): 1419–1440. Bibcode:1984MWRv..112.1419G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1984)112<1419:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center; E.B. Gunther and R.L. Cross; National Weather Service Western Region. "Annual data and verification tabulation, eastern North Pacific tropical storms and hurricanes, 1983". National Weather Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Reid Moran; Scientific Publications Committee (July 26, 1996). "The Flora of Guadeloupe Island". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. California Academy of Sciences (19). Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- "The Nation's Weather: PM cycle". The Associated Press. August 11, 1983.

- Cythina Green (August 12, 1983). "Domestic News". Associated Press.

- "The Nation's Weather". Associated Press. August 13, 1983.

- "Wind rain, slam into US coasts". The Deseret News. Associated Press. p. 2.

- "The Weather". Harlan Daily News. Associated Press. August 13, 1983. p. 7. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- Dennis McTighe (August 4, 2011). "Legalize El Nino!". Laguna Beach Independent. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- "Domestic News". United Press International. August 12, 1983.

- "The Nation's Weather". Associated Press. August 16, 1983.

- "Spawned By Storms". The Press-Courier. Associated Press. August 17, 1983. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Micheal Harris (August 17, 1983). "Domestic News". United Press International.

- "Ismael lashes California Coast". Gainesville Sun. Associated Press. August 17, 1983. p. 2. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- David Langford (August 17, 1983). "Domestic News". Associated Press.

- Jeff Wilson (August 18, 1983). "Domestic News". United Press International.

- Cathy Lewandowsky (August 16, 1983). "Mercury again climbs toward 100 in Plains". United Press International.

- "Tropical Storm Isolates 50,000 in California". Youngstown Vindicator. Associated Press. August 17, 1983. p. 9. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "Storms rake LA area". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. August 17, 1983. p. 3. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Aluival Fan Task Force (2005). "1 AFTF Study Area Flood History" (PDF). California State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 20, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Nation's Weather". Associated Press. August 11, 1983.

- The Hydrology Geomorphology Interface: Rainfall, Floods, Sedimentation, Land. International Association of Hydrological Sciences. 2000. p. 203. ISBN 9781901502169. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- Garcia, Perez; A.V. Douglas (July 24, 1989). "On the Status cover". Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. 83 (5–6): 219–234. doi:10.1159/000090433. PMID 16374074.

- "Domestic News". United Press International. August 12, 1983.

- "The Nation's Weather". Associated Press. August 12, 1983.

- "Crew hope to open road due to mudslide". United Press International. August 13, 1983.

- "The Nation's Weather". Associated Press. August 17, 1983.

- "Ismael Lashes California Coast". Gainseville Sun. Associated Press. August 17, 1983. p. 2. Retrieved May 31, 2013.