Hurricane Isbell

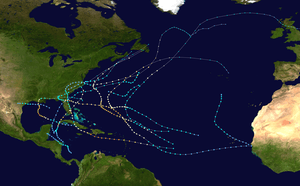

Hurricane Isbell was the final hurricane to affect the United States during the 1964 season. The eleventh tropical storm and sixth hurricane of the season. Isbell developed from a dissipating cold front in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on October 8. The depression initially remained disorganized as it track northwestward, but strengthened into Tropical Storm Isbell on October 13. Re-curving northeastward, Isbell quickly strengthened further and reached hurricane status by later that day. Late on October 13, Isbell made landfall in the Pinar del Río Province of Cuba. The storm continued strengthening and peaked as a Category 3 hurricane on the following day. Isbell moved northeastward and made landfall near Everglades, Florida, late on October 14. After reaching the Atlantic on the following day, the storm began to weaken. Isbell turned northward and continued weakening, before transitioning to an extratropical cyclone while located just offshore eastern North Carolina on October 16.

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

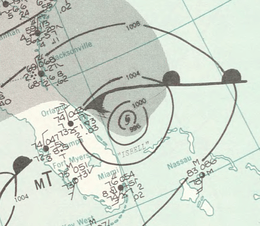

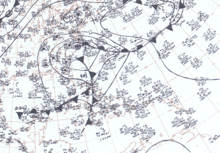

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on October 15, 1964 | |

| Formed | October 8, 1964 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 19, 1964 |

| (Extratropical after October 16) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 964 mbar (hPa); 28.47 inHg |

| Fatalities | 7 total |

| Damage | $30 million (1964 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| Part of the 1964 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The storm produced strong winds throughout western Cuba. Hundreds of homes were destroyed, as were several tobacco warehouses. There was at least $20 million in damage and four deaths in Cuba, three of them caused by collapsing houses in the Guane area. Several tornadoes in Florida caused significant damage. Throughout the state, 1 house was destroyed, 33 were severely damaged, and 631 suffered minor impact. Additionally, 66 trailers were destroyed and 88 were inflicted with major damage. Three deaths occurred in the state, one due to a heart attack and two from drowning in Florida Keys when their shrimp boat sank. Because the storm weakened considerably, impact in North Carolina was generally minor. The storm also spawned at least nine tornadoes in the state, which demolished trailers and unroofed homes and other buildings in several communities. Damage throughout the United States totaled $10 million.

Meteorological history

Hurricane Isbell was first identified as a weak tropical disturbance on October 7, 1964 over the western Caribbean Sea. Situated to the south of a diffuse trough, the system remained weak and relatively disorganized as it moved generally northwest near Honduras and Nicaragua. Despite the presence of an upper-level anticyclone, which promotes favorable outflow for tropical cyclones and aids in tropical cyclogenesis, a lack of distinct low-level inflow inhibited intensification. Additionally, an area of warm mid-tropospheric air was present within the cyclone. Though a disheveled system,[1] it is analyzed to have become a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on October 8. The following day, the depression skirted the eastern coast of Honduras.[2] Operationally, it was not until October 10 that the Weather Bureau initiated advisories on the depression.[1] On that date, a weather reconnaissance mission into the system found a weak low-level circulation with a barometric pressure of 1007.3 mb (hPa; 29.75 inHg) and winds of 20–30 mph (30–45 km/h) in squalls.[3] Throughout October 11 and 12, the depression slowly executed a tight cyclonic loop over the northwestern Caribbean Sea. It finally organized into a tropical storm and was given the name Isbell by 00:00 UTC on October 13 after completing the loop and acquiring a north-northeast trajectory.[2]

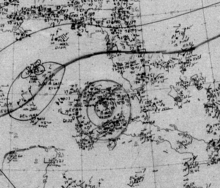

Throughout October 13, marked intensification of the cyclone occurred.[1] Over a 24‑hour span, ending at 18:00 UTC, its central pressure fell from 1005 mb (hPa; 29.68 inHg) to 979 mb (hPa; 28.91 inHg) which was reflected in Isbell's winds more than doubling from 35 mph (55 km/h) to 90 mph (150 km/h).[2] Shortly thereafter, the storm made landfall in extreme western Cuba, near Guane, before emerging over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[1] Isbell's brief stint over land did not hinder development, which continued unabated until 12:00 UTC on October 14 at which time it reached its maximum intensity. Situated to the south of Key West, Florida, Isbell attained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) which ranks it as a Category 3 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. Additionally, its central pressure bottomed out at 964 mb (hPa; 28.47 inHg).[2] Around this time, a new low-pressure area formed 300 mi (480 km) to Isbell's northwest over the Gulf in response to a powerful cold-core low over the Mississippi Valley. The cyclonic flow of this second system brought cool, dry air from the north and circulated it into the hurricane. This in turn caused the storm to become asymmetric in structure with radar imagery indicating little to no reflectivity along the western periphery of the hurricane.[1]

The degrading structure of Isbell resulted in some weakening as it accelerated toward Florida. At 22:00 UTC on October 14, the hurricane made landfall near Everglades City as a Category 2 with sustained winds between 100 and 110 mph (160 and 175 km/h).[1][4] Within five hours, the system cleared the Florida Peninsula and emerged over the western Atlantic Ocean north of West Palm Beach.[5] The storm's passage over land resulted in notable weakening, though Isbell remained of hurricane-strength. During the afternoon of October 15, the low that had formed the previous day induced a northward turn of the cyclone and directed it toward North Carolina, a result of what is known as the Fujiwhara effect.[1] Thereafter, the two systems began to intertwine as Isbell began transitioning into an extratropical cyclone; rapid weakening accompanied this phase.[6] Isbell completed this process by 12:00 UTC on October 16 as it moved onshore near Morehead City, North Carolina.[2][6] On October 17 the two non-tropical systems merged into a single storm over the Outer Banks.[6] Isbell's remnants emerged back over the Atlantic Ocean on October 18 near the Delmarva Peninsula before accelerating northeast. The system was last noted on October 19 as it moved over Atlantic Canada.[7]

Preparations

| Warning type | Date | Time issued | State | Areas/changes to previous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurricane warning | October 13 | 22:00 UTC | Florida | Dry Tortugas |

| Hurricane watch | Lower Florida Keys to Tampa | |||

| Gale warning | Dry Tortugas to Marathon | |||

| Hurricane watch | October 14 | 01:00 UTC | Florida | Extended east to Key Largo |

| Gale warning | Extended east to Key Largo | |||

| Hurricane warning | 04:00 UTC | Florida | Extended east to Key West and Marathon; raised for areas between Flamingo north to Ft. Myers | |

| Hurricane watch | 10:00 UTC | Florida | Extended northward to Cape Kennedy, including Lake Okeechobee | |

| Gale warning | ||||

| Hurricane warning | 16:00 UTC | Florida | Fort Lauderdale to Vero Beach, including Lake Okeechobee | |

| Hurricane warning | 22:00 UTC | Florida | Extended northward to Cape Kennedy | |

| Hurricane watch | Extended northward to Daytona Beach | |||

| Gale warning | ||||

| Advisories discontinued | October 15 | 01:00 UTC | Florida | Tampa southward to the Dry Tortugas |

| Advisories discontinued | 04:00 UTC | Florida | The west coast of Florida south of Fort Lauderdale and the east coast of Florida south of Cape Kennedy | |

| Advisories discontinued | 10:00 UTC | Florida | All advisories discontinued | |

| Gale warning | North Carolina, Virginia |

Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, northward to the Virginia Capes | ||

| Hurricane watch | 14:30 UTC | South Carolina, North Carolina |

Charleston, South Carolina, northward, encompassing the entire North Carolina coastline | |

| Gale warning | South Carolina, North Carolina |

Charleston, South Carolina, northward, encompassing the entire North Carolina coastline | ||

| Hurricane warning | 16:00 UTC | South Carolina, North Carolina |

Georgetown, South Carolina, northward to Morehead City, North Carolina |

In Cuba, thousands were evacuated due to flooding lowlands.[8] Advisories were broadcast and issued warning of the possibility of heavy rains and winds, isolated small hail, and possible isolated tornadoes in Florida from 21:00 UTC on October 14 to 02:00 UTC on October 15. The aviation severe weather forecast also warned residents in south and central Florida of up to 0.75 in (19 mm) of hail, gusts of up to 53 mph (85 km/h), and the potential for tornadic activity. Flood warnings were also issued, with predictions of flooding 4 ft (1.2 m) above flood stage.[9] Emergency preparations at Key West's weather office were made. In the morning hours of October 13, the office alerted city, county, and military officials. In the afternoon, they completed office preparations and scheduling. On October 14, the office requested radio stations to stay on the air and relayed hourly reports.[10]

In North Carolina, some tidal flooding was also forecast. People were warned to tune to television and radio broadcasts.[11] On October 15, as Isbell rapidly crossed Florida, forecasters at the Charleston, South Carolina Weather Bureau warned of high tides of up to 12 ft (3.7 m), 5 ft (1.5 m) above flood-stage, from South Carolina into North Carolina. Owing to the continued northeastward movement of the storm, tides ultimately did not exceed 2 ft (0.61 m) in South Carolina.[12] Across coastal areas of North Carolina, alerts for severe thunderstorms, tornadoes, and high tides were raised; however, the storm greatly diminished before reaching shore and little damage materialized.[13] Moderate rains along the lower Neuse River basin were expected to prolong flooding triggered by Hurricane Hilda and its remnants earlier in October.[14] Small craft advisories were raised northward to Provincetown, Massachusetts, through October 18.[15]

Impact

Cuba

Skirting the extreme western coast of Cuba on October 13, the storm produced gusts estimated at 100 mph (160 km/h) in Pinar del Rio Province.[16] The highest measured sustained winds were 85 mph (140 km/h) in Guane and 70 mph (110 km/h) at Rancho-Boyeros Airport in the capital city of Havana. Additionally, pressures at the city fell to 979 mbar (hPa; 28.91 inHg).[1] Heavy rains caused rivers to over-top their banks, forcing thousands of people to evacuate.[17] Three fatalities occurred in Guane due to collapsing homes.[1][18] A fourth fatality took place elsewhere in Cuba.[19] Numerous homes were damaged or destroyed by the storm, with exact numbers unknown. The region's tobacco crop also sustained considerable losses with fields and warehouses destroyed.[16] The damage to agriculture compounded economic losses in Cuba that resulted from Hurricane Flora in September 1963, which devastated the nation, as well as impacts from Hurricanes Cleo and Hilda earlier in 1964.[20] The combined effects of Cleo, Hilda, and Isbell resulted in economic losses of approximately $100 million in the country, of which at least $20 million was directly attributed to Isbell.[21]

Florida

Though Isbell struck the state as a Category 2 hurricane,[4] no winds in excess of 100 mph (160 km/h) were reported. Measurements peaked at 90 mph (150 km/h) at both Everglades City and Indiantown. Hurricane-force gusts were measured in Belle Glade, Fort Lauderdale, Key West, Pompano Beach, and West Palm Beach. Atmospheric pressures fell to 970.7 mb (hPa; 28.67 inHg) in the Dry Tortugas and 977.5 mb (hPa; 28.87 inHg) on the mainland in Juno Beach.[1] Rainfall in the state was relatively limited owing to the brisk movement of the storm, though a frontal system immediately preceding the hurricane brought heavy rains to the state. A peak total of 9.46 in (240 mm) was measured in West Palm Beach, though an estimated 80% of this was attributable to the front.[7] Amounts from the hurricane itself were likely around 5 in (130 mm). No major storm surge was reported during Isbell's passage due to greatly weaker winds in the back half of the storm. Tides in Key West rose 4 to 5 ft (1.2 to 1.5 m) above normal.[1]

Throughout Florida, three people were killed in relation to the storm and no more than $10 million in damage occurred, with more than half of which was attributed to agricultural losses.[1] In addition, 76 people were injured, 12 of whom required hospitalization. Structural damage was relatively limited, with only 63 homes and businesses, mostly trailers, being destroyed; 159 other structures sustained major damage while a further 631 experienced minor damage.[22] The majority of damage from Isbell was not from the hurricane itself but rather tornadoes spawned by its outer bands.[1] At least nine, and as many as twelve, tornadoes affected the state with the greatest effects being felt in the Miami metropolitan area. All storm-related injuries were attributed to these tornadoes as well as the majority of structural damage.[23] According to the National Climatic Data Center, four of these tornadoes were of F2 intensity.[24]

Despite the close passage of the storm to the Florida Keys, damage in the area was light and amounted to $175,000.[1] Of this, $125,000 was attributed to structural damage. Hurricane-force winds in the archipelago only lasted 15 minutes and gale-force winds occurred over a 5 hour span. The brevity of damaging winds limited the effects of the storm. Most damage was constrained to downed trees, signs, and power poles. Two trailers were overturned, however, and an oil barge sank in the Key West Harbor.[25] Two people drowned after their shrimp boat was destroyed.[1] In and around the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park, Royal Palms, and Royal Poincianas were defoliated by the hurricane's winds. Downed trees and power lines in Collier County temporarily left many customers without phone and electrical service. Residents in nearby Lee Cypress stated that the effects from Isbell were worse than Hurricane Donna which struck the region as a Category 4 in September 1960.[26]

Palm Beach County was the most affected area, accounting for more than half of the losses,[22][27] and approximately $700,000 in damage.[28] One indirect death occurred when a man suffered a heart attack in Lake Worth while installing storm shutters.[1][28] At least three tornadoes were spawned in Palm Beach County. The strongest was an F2 that struck a trailer park in Briny Breezes, damaging numerous trailers and injuring 22 people. Shortly thereafter the same tornado or possibly a second one struck Boynton Beach, injuring three people and damaging several structures.[23][24] The event lasted roughly 20 minutes and the tornadoes moved along a path 10 mi (16 km) long.[29][30] Another tornado in Boca Raton caused a number of minor injuries. In West Palm Beach, a twister that crossed the intersection of State Roads 802 and 809 damaged adjacent properties and injured several people.[23] Throughout Palm Beach County, 492 homes suffered damage, while 36 mobile homes were demolished and 60 others were inflicted major impact. Additionally, 33 farm buildings and 9 small businesses were severely damaged or destroyed.[22]

In Martin County, an F2 was spawned in Hobe Sound and affected the area near U.S. Route 1.[23] About 39 homes and 13 mobile homes were damaged, while two farm buildings and two businesses also received impact.[22] The fourth F2 tornado was spawned in Brevard County near Eau Gallie. It caused extensive damage and injured 17 people in the Orange Court trailer park.[23][24] Collectively, 35 homes in Flagler and Volusia counties were damaged.[22]

The Carolinas and elsewhere

Heavy rains associated with Isbell and a nearby non-tropical low resulted in heavy rains across The Carolinas on October 15 and 16. In and around the Columbia, South Carolina area, 3 to 6 in (76 to 152 mm) of rain fell, with a peak of 6.11 in (155 mm) in the city itself. Significant flooding took place along all rivers in the state;[31] the Broad River crested at 32.1 ft (9.8 m), its highest level since 1940, in Blair. The Pee Dee River rose to 39 ft (12 m) at Cheraw by October 18, roughly 9 ft (2.7 m) above flood-stage.[32] The cotton crop sustained the greatest losses during the event, with damage estimated in excess of $1 million.[31] Along the coast, tides rose to 6.2 ft (1.9 m), 2.1 ft (0.64 m) above normal, in Charleston Harbor. What little coastal flooding took place mostly resulted from wave run-up rather than tidal flooding. Some beach erosion occurred in exposed areas.[33]

Much of North Carolina was affected by Isbell with rain extending into interior parts of the state. Totals were generally light, however, and peaked at around 5 in (130 mm) in eastern areas. Some flash flooding took place in the Piedmont, though overall effects were minimal.[34] In the Blue Ridge Mountains, the French Broad River topped its banks and prompted evacuations in Hot Springs and Marshall.[15] The greatest impacts were felt along the Neuse River in Kinston within Lenoir County. Rains from Isbell exacerbated ongoing floods in the area, resulting in heavy damage to many homes.[32] A man was swept away by swift currents near a Duke Energy steam plant in Cliffside; however, it is unknown if he perished or was later rescued.[35] Losses to the peanut crop were extensive, though no monetary value is available.[1] With the storm arriving at low-tide, no notable coastal flooding occurred.[34] The significant weakening of Isbell prior to landfall also lessened the effects from wind as gale-force winds were mostly constrained to coastal areas; a peak gust of 75 mph (120 km/h) was measured in Elizabeth City.[1]

Elsewhere along the East Coast, the remnants of Isbell produced generally light to moderate rain. A localized maximum of around 5 in (130 mm) occurred in Massachusetts as the system began to dissipate.[7] Immediately following the storm, an unseasonably strong cold front brought near-freezing temperatures to Virginia, resulting in frost. The combination of the cold air and the hurricane prevented any peanut bumper crop harvesting in the state.[36]

See also

References

- Gordon E. Dunn (March 1965). "The Hurricane Season of 1964: Individual Tropical Cyclones: Hurricane Isbell, October 8–16" (.PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 93 (3): 185–187. Bibcode:1965MWRv...93..175D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-93.3.175. ISSN 1520-0493. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- Hurricane Research Division (April 1, 2014). "Atlantic Hurricane Best Track (HURDAT version 2)" (.TXT). National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- Hurricane Isbell October 12 - 16, 1964 Preliminary Reports With Advisories and Bulletins Issued (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1964. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- Hurricane Research Division (February 2008). "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851-2007". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (.TXT) on September 21, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Land Based Radar Track of Eye of Hurricane Isbell (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1964. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- E. Hill (1964). Hurricane Isbell (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 2. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- David M. Roth (2014). "Hurricane Isbell - October 11-19, 1964". Weather Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "Isbell Takes Dead Aim on North Carolina Coast". The Daily Times News. Associated Press. October 15, 1964.

- Magor (October 14, 1964). "Severe Weather Forecast Number 460" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "Emergency Procedures during Hurricane Isbell". United States Weather Bureau Airport Station Key West, Florida. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 21, 1964. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Duke (October 15, 1964). "Tide Statement No. 1". United States Weather Bureau Office Wilmington, North Carolina. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- John A. Cummings (October 16, 1964). "Local Statement: Hurricane Isbell" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office in Charleston, South Carolina. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- "Power Lost by Hurricane Isbell". The Daily Telegram. Norfolk, Virginia. United Press International. October 17, 1964. p. 15. Retrieved June 17, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- Carney (October 16, 1964). "US Weather Bureau Raleigh Duram Airport River Bulletin" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office in Raleigh, North Carolina. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- "Hurricane Remnants Now At Sea". San Antonio Express. Norfolk, Virginia. Associated Press. October 18, 1964. p. 56. Retrieved June 20, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Isbell Smashes Into Cuba; May Hit Florida Tonight". Miami, Florida: The News-Palladium. Associated Press. October 14, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 17, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Florida Keys Hit By Isbell; Storm Slams Across Cuba, Ruins Crops". The Emporia Gazette. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 14, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved June 17, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Hurricane Isbell" (.GIF). El Mundo. Havana, Cuba. October 14, 1964. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- "North Carolina Isbell's Target". Janesville Daily Gazette. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 15, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 17, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Hurricane Hits Cuban Province". Ironwood Daily Globe. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 14, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 17, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- Don Bohning (October 18, 1964). "4 Storms in a Year Strain Cuban Economy" (.GIF). The Miami Herald. p. 8B. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- Hurricane Isbell Florida Damage Summary (.GIF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Robert M. White, United States Weather Bureau (1964). Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: October 1964 (PDF). National Climatic Data Center (Report). 6. Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "October 14, 1964 Tornado Summary for Florida". National Climatic Data Center. Tornado History Project. 2014. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Preliminary Report on Hurricane Isbell" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office in Key West, Florida. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 15, 1964. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Fred G. Winter (October 16, 1964). "Hurricane Isbell Damage Runs Half-Million In Collier County" (.GIF). Ft. Myers News Press. Naples, Florida. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- Hurricane Isbell Florida Damage Summary (.GIF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1964. p. 2. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Elliott Kleinberg (October 16, 2014). "1964 hurricane spawned tornado that smashed Briny Breezes". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Jack L. Hudnall (October 14, 1964). Summary of Effects of Hurricane Isbell on Eastern Palm Beach County, Florida (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Jack L. Hudnall (October 14, 1964). Summary of Effects of Hurricane Isbell on Eastern Palm Beach County, Florida (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 2. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Hurricane Isbell" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 17, 1964. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Cleanup Begins Of Tar Heel Flood Areas". Florence Morning News. Associated Press. October 19, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved June 20, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Preliminary Report on Hurricane Isbell October 14–17, 1964" (.GIF). United States Weather Bureau Office in Charleston, South Carolina. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 17, 1964. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- Albert V. Hardy (October 26, 1964). "Hurricane Isbell in North Carolina" (.GIF). Office of Climatology. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- "Winded Isbell Quits; Leaves Sky All Clear". The Odessa American. Norfolk, Virginia. Associated Press. October 18, 1964. p. 3. Retrieved June 20, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)

- "Bumper Peanut Ruled Out". The Progress-Index. Suffolk, Virginia. Associated Press. October 19, 1964. p. 10. Retrieved June 20, 2014. – via Newspapers.com (subscription required)