Alveolar process

The alveolar process (/ælˈviːələr/[1]) (also called the alveolar bone) is the thickened ridge of bone that contains the tooth sockets (dental alveoli) on the jaw bones that hold teeth. In humans, the tooth-bearing bones are the maxilla and the mandible.[2] The curved part of each alveolar process on the jaw is called the alveolar arch.

| Alveolar process | |

|---|---|

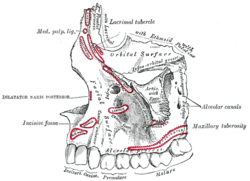

Left maxilla. Outer surface. (Alveolar process visible at bottom.) | |

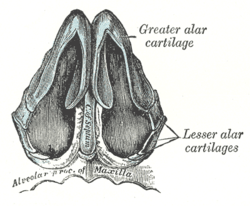

Cartilages of the nose, seen from below. (Alveolar process of maxilla visible at bottom. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os alveolaris |

| MeSH | D000539 |

| TA | A02.1.12.035 |

| FMA | 52897 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Structure

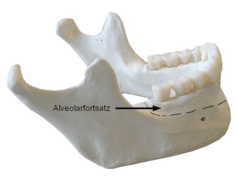

On the maxilla, the alveolar process is a ridge on the inferior surface, and on the mandible it is a ridge on the superior surface. It makes up the thickest part of the maxillae.

The alveolar process contains a region of compact bone adjacent to the periodontal ligament (PDL), called the lamina dura when viewed on radiographs. It is this part which is attached to the cementum of the roots by the periodontal ligament. It is uniformly radiopaque (or lighter). Integrity of the lamina dura is important when studying radiographs for pathological lesions.

The alveolar process has a supporting bone, both of which have the same components: fibers, cells, intercellular substances, nerves, blood vessels, and lymphatics.

The alveolar process is the lining of the tooth socket or alveolus (plural, alveoli). Although the alveolar process is composed of compact bone, it may be called the cribriform plate because it contains numerous holes where Volkmann canals pass from the alveolar bone into the PDL. The alveolar bone proper is also called bundle bone because Sharpey fibers, a part of the fibers of the PDL, are inserted here. Similar to those of the cemental surface, Sharpey fibers in alveolar bone proper are each inserted at 90 degrees, or at a right angle, but are fewer in number, although thicker in diameter than those present in cementum. As in cellular cementum, Sharpey fibers in bone are generally mineralized only partially at their periphery.

The alveolar crest is the most cervical rim of the alveolar bone proper. In a healthy situation, the alveolar crest is slightly apical to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) by approximately 1.5 to 2 mm.[2] The alveolar crests of neighboring teeth are also uniform in height along the jaw in healthy situation.[3]

The supporting alveolar bone consists of both cortical bone and trabecular bone. The cortical bone, or cortical plates, consists of plates of compact bone on the facial and lingual surfaces of the alveolar bone. These cortical plates are usually about 1.5 to 3 mm thick over posterior teeth, but the thickness is highly variable around anterior teeth.[2] The trabecular bone consists of cancellous bone that is located between the alveolar bone proper and the plates of cortical bone. The alveolar bone between two neighboring teeth is the interdental septum (or interdental bone).[3]

Composition[4]

Inorganic matrix

Alveolar bone is 67% inorganic material by weight. The inorganic material is composed mainly of the minerals calcium and phosphate. The mineral content is mostly in the form of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals.

Organic matrix

The remaining alveolar bone is organic material (33%). The organic material consists of collagen and non-collagenous material. The cellular component of bone consists of osteoblasts, osteocytes and osteoclasts.

- Osteoblasts are usually cuboidal and slightly elongated in shape. They synthesise both collagenous ad non-collagenous bone proteins. These cells have a high level of alkaline phosphatase on the outer surface of their plasma membrane. The functions of osteoblasts are bone formation by synthesising the organic matrix of bone, cell to cell communication and maintenance of bone matrix.

- Osteocytes are modified osteoblasts which become entrapped in lacunae during the secretion of bone matrix. The osteocytes have processes called canaliculi that radiate from the lacunae. These canaliculi bring oxygen and nutrients to the osteocytes through blood and remove metabolic waste products.

- Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells. They are found in Howship’s lacunae.

Clinical significance

Alveolar bone loss

Bone is lost through the process of resorption which involves osteoclasts breaking down the hard tissue of bone. A key indication of resorption is when scalloped erosion occurs. This is also known as Howship’s lacuna.[5] The resorption phase lasts as long as the lifespan of the osteoclast which is around 8 to 10 days. After this resorption phase, the osteoclast can continue resorbing surfaces in another cycle or carry out apoptosis. A repair phase follows the resorption phase which lasts over 3 months. In patients with periodontal disease, inflammation lasts longer and during the repair phase, resorption may override any bone formation. This results in a net loss of alveolar bone.[6]

Alveolar bone loss is closely associated with periodontal disease. Periodontal disease is the inflammation of the gums. Studies in osteoimmunology have proposed 2 models for alveolar bone loss. One model states that inflammation is triggered by a periodontal pathogen which activates the acquired immune system to inhibit bone coupling by limiting new bone formation after resorption.[7] Another model states that cytokinesis may inhibit the differentiation of osteoblasts from their precursors, therefore limiting bone formation. This results in a net loss of alveolar bone.[8]

Developmental disturbances

The developmental disturbance of anodontia (or hypodontia, if only one tooth), in which tooth germs are congenitally absent, may affect the development of the alveolar processes. This occurrence can prevent the alveolar processes of either the maxillae or the mandible from developing. Proper development is impossible because the alveolar unit of each dental arch must form in response to the tooth germs in the area.[3]

Pathology

After extraction of a tooth, the clot in the alveolus fills in with immature bone, which later is remodeled into mature secondary bone. However, with the partial or total loss of teeth, the alveolar process undergoes resorption. The underlying basal bone of the body of the maxilla or mandible remains less affected, however, because it does not need the presence of teeth to remain viable. The loss of alveolar bone, coupled with attrition of the teeth, causes a loss of height of the lower third of the vertical dimension of the face when the teeth are in maximum intercuspation. The extent of this loss is determined based on clinical judgment using the Golden Proportions.[3]

The density of the alveolar bone in a given area also determines the route that dental infection takes with abscess formation, as well as the efficacy of local infiltration during the use of local anesthesia. In addition, the differences in alveolar process density determine the easiest and most convenient areas of bony fracture to be used, if needed during tooth extraction of impacted teeth.[3]

During chronic periodontal disease that has affected the periodontium (periodontitis), localized bone tissue is also lost.

Alveolar bone grafting

Alveolar bone grafting in the mixed dentition is an essential part of the reconstructive journey for cleft lip and palate patients. The reconstruction of the alveolar cleft can provide both aesthetic and practical advantages to the patient.[9] Alveolar bone grafting can also bring about the following benefits: stabilisation of the maxillary arch; aid of eruption of the canine and sometimes lateral incisor eruption; offering bony support to the teeth lying next to the cleft; elevate the alar base of the nose; aid sealing of oro-nasal fistula; permit insertion of a titanium fixture in the grafted region and achieve good periodontal conditions within and next to the cleft.[10] The timing of the alveolar bone grafting takes into consideration both eruption of the canine and lateral incisor. The optimal time for bone grafting surgery is when a thin shell of bone still covers the soon erupting lateral incisor or canine tooth close to the cleft.[10]

- Primary bone grafting: Primary bone grafting is believed to: eliminate bone deficiency, stabilize pre-maxilla, synthesize new bone matrix for eruption of teeth in the cleft area and augment the alar base. However, the early bone grafting procedure is abandoned in most cleft lip and palate centres around the world due to many disadvantages, including serious growth disturbances of the middle third of the facial skeleton. The operative technique that involves the vomero-premaxillary suture was found to inhibit maxillary growth.[10]

- Secondary bone grafting: Secondary bone grafting, also referred to as bone grafting in the mixed dentition, became a well-established procedure after abandoning primary bone grafting. The pre-requisites include precise timing, operating technique, and acceptably vascularized soft tissue. The advantages of primary bone grafting, which are allowing tooth eruption through the grafted bone, are retained. Furthermore, secondary bone grafting stabilizes the maxillary arch, thus enhancing the conditions for prosthodontic treatment such as crowns, bridges and implants. It also aids eruption of teeth, boosting the amount of bony tissue on the alveolar crest, permitting orthodontic treatment. Bony support to teeth adjacent to the cleft is a pre-requisite for orthodontic closure of the teeth in the cleft region. Hence, better hygienic conditions will be achieved which helps to lessen formation of caries and periodontal inflammation. Speech problems caused by irregular positioning of articulators, or leakage of air via the oronasal communication, may also be improved. Secondary bone grafting can also be used to augment the alar base of the nose to achieve symmetry with the non-cleft side, thereby enhancing facial appearance.[10]

- Late secondary bone grafting: Bone grafting has a lower success rate when performed after canine has erupted as compared to before the eruption. It has been found that the possibility for orthodontic closure of the cleft in the dental arch is smaller in patients grafted before canine eruption than those after the canine eruption. The surgical procedure includes drilling of several small openings through the cortical layer into the cancellous layer, facilitating growth of blood vessels into the graft.[10]

Additional images

- This X-ray film reveals some bone loss on the right side of the mandible. The associated teeth exhibit poor crown-to-root ratios and may be subject to secondary occlusal trauma.

Alveolar process

Alveolar process- Alveolar process of maxilla

Alveolar part of mandible

Alveolar part of mandible

References

- Entry "alveolar" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- Ten Cate's Oral Histology, Nanci, Elsevier, 2013, page 219

- Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 176

- Shalu, Bathla (2017-04-30). Textbook of periodontics / Shalu Bathla ; foreword SG Damle. Damle, S. G. (First ed.). New Delhi. ISBN 978-9386261731. OCLC 971599883.

- Bar-Shavit, Zvi (2007-12-01). "The osteoclast: a multinucleated, hematopoietic-origin, bone-resorbing osteoimmune cell". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 102 (5): 1130–1139. doi:10.1002/jcb.21553. ISSN 0730-2312. PMID 17955494.

- R., Garant, Philias (2003). Oral cells and tissues. Chicago: Quintessence Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0867154290. OCLC 51892824.

- Leone, Cataldo W.; Bokhadhoor, Haneen; Kuo, David; Desta, Tesfahun; Yang, Julia; Siqueira, Michelle F.; Amar, Salomon; Graves, Dana T. (April 2006). "Immunization enhances inflammation and tissue destruction in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis". Infection and Immunity. 74 (4): 2286–2292. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.4.2286-2292.2006. ISSN 0019-9567. PMC 1418897. PMID 16552059.

- Graves, D.T.; Li, J.; Cochran, D.L. (2011). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Journal of Dental Research. 90 (2): 143–153. doi:10.1177/0022034510385236. PMC 3144100. PMID 21135192.

- Coots, Bradley K. (November 2012). "Alveolar bone grafting: past, present, and new horizons". Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 26 (4): 178–183. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1333887. ISSN 1535-2188. PMC 3706037. PMID 24179451.

- Lilja, Jan (October 2009). "Alveolar bone grafting". Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 42 Suppl (3): S110–115. doi:10.4103/0970-0358.57200. ISSN 1998-376X. PMC 2825060. PMID 19884665.

External links

- Photo of model at Waynesburg College skeleton/alveolarprocess

- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon – illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.

- Diagram at case.edu