History of baseball

References to baseball date back to the 1700s where in England it was known as a game called rounders. Rounders is referenced in 1744 in the children's book A Little Pretty Pocket-Book where it was called Baseball. In 1871 the first professional league, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, was founded. Five years later, the National League was created; it was followed by the Baseball early in the 20th century was characterized by low-scoring games, but the

| Part of a series on the |

| History of baseball |

|---|

| By country |

| Other topics |

| Related games |

| Baseball portal |

Origins

_in_the_Cantigas_de_Santa_Maria.jpg)

The evolution of baseball from older bat-and-ball games is difficult to trace with precision. A French manuscript from 1344 contains an illustration of clerics playing a game, possibly la soule, with similarities to baseball.[1] Other old French games such as thèque, la balle au bâton, and la balle empoisonnée also appear to be related.[2] Consensus once held that today's baseball is a North American development from the older game rounders, popular in Great Britain and Ireland. Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game (2005), by David Block, suggests that the game originated in England; recently uncovered historical evidence supports this position. Block argues that rounders and early baseball were actually regional variants of each other, and that the game's most direct antecedents are the English games of stoolball and "tut-ball".[3] It has long been believed that cricket also descended from such games, though evidence uncovered in early 2009 suggests that cricket may have been imported to England from Flanders.[4]

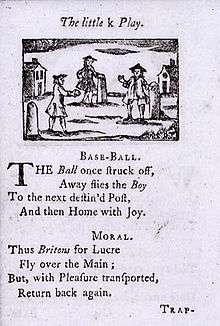

The earliest known reference to baseball is in a 1744 British children's publication, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, by John Newbery. It contains a rhymed description of "base-ball" and a woodcut that shows a field set-up somewhat similar to the modern game—though in a triangular rather than diamond configuration, and with posts instead of ground-level bases.[6] Block discovered that the first recorded game of "Bass-Ball" took place in 1749 in Surrey, and featured the Prince of Wales as a player.[7] William Bray, an English lawyer, recorded a game of baseball on Easter Monday 1755 in Guildford, Surrey.[8] This early form of the game was apparently brought to Canada by English immigrants. Rounders was also brought to the United States by Canadians of both British and Irish ancestry. The first known American reference to baseball appears in a 1791 Pittsfield, Massachusetts town bylaw prohibiting the playing of the game near the town's new meeting house.[9] By 1796, a version of the game was well known enough to earn a mention in a German scholar's book on popular pastimes. As described by Johann Gutsmuths, "englische Base-ball" involved a contest between two teams, in which "the batter has three attempts to hit the ball while at the home plate." Only one out was required to retire a side.[10]

In 1828, William Clarke in London published the second edition of The Boy's Own Book, which included the rules of rounders and contained the first printed description in English of a bat and ball base-running game played on a diamond.[11] The following year, the book was published in Boston, Massachusetts.[12]

By the early 1830s, there were reports of a variety of uncodified bat-and-ball games recognizable as early forms of baseball being played around North America. These games were often referred to locally as "town ball", though other names such as "round-ball" and "base-ball" were also used.[13] Among the earliest examples to receive a detailed description—albeit five decades after the fact, in a letter from an attendee to Sporting Life magazine—took place in Beachville, Ontario, in 1838. There were many similarities to modern baseball, and some crucial differences: five bases (or byes); first bye just 18 feet (5.5 m) from the home bye; batter out if a hit ball was caught after the first bounce.[14] The once widely accepted story that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in Cooperstown, New York, in 1839 has been conclusively debunked by sports historians.[15] The Doubleday myth appeared after a dispute arose about the origins of baseball and whether it had been invented in the United States or developed as a variation of rounders.[16] The theory that the sport was created in the U.S. was backed by Chicago Cubs president Albert Spalding and National League president Abraham G. Mills. In 1889, Mills gave a speech declaring that baseball was American, which he said was determined through "patriotism and research"; a crowd of about 300 people responding by chanting "No rounders!"[16] The rounders theory was supported by prominent sportswriter Henry Chadwick, a native of Britain who noted common factors between rounders and baseball in a 1903 article.[17] In 1905, Spalding called for an investigation into how the sport was invented. Chadwick supported the idea, and later in the year the Mills commission was formed. Spalding instructed the commission to decide between the American game of "Old Cat" and rounders as baseball's predecessor. Seven men served on the commission, including Mills. Spalding chose the committee's members, picking men who supported his theory and excluding supporters of the rounders claim, such as Chadwick.[18]

.jpg)

In 1845, Alexander Cartwright, a member of New York City's Knickerbocker Club, produced a code of baseball rules now called the Knickerbocker Rules.[19] The practice, common to bat-and-ball games of the day, of "soaking" or "plugging"—effecting a putout by hitting a runner with a thrown ball—was barred. The rules thus facilitated the use of a smaller, harder ball than had been common. Several other rules also brought the Knickerbockers' game close to the modern one, though a ball caught on the first bounce was, again, an out and only underhand pitching was allowed.[20] While there are reports that the New York Knickerbockers played games in 1845, the contest long recognized as the first officially recorded baseball game in U.S. history took place on June 19, 1846, in Hoboken, New Jersey: the "New York Nine" defeated the Knickerbockers, 23–1, in four innings.[21] With the Knickerbocker code as the basis, the rules of modern baseball continued to evolve over the next half-century.[22]

In the United States

Professional leagues develop

In the mid-1850s, a baseball craze hit the New York metropolitan area.[23] By 1856, local journals were referring to baseball as the "national pastime" or "national game."[24] A year later, 16 area clubs formed the sport's first governing body, the National Association of Base Ball Players. In 1863, the organization disallowed putouts made by catching a fair ball on the first bounce. Four years later, it barred participation by African Americans.[25] The game's commercial potential was developing: in 1869 the first fully professional baseball club, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, was formed and went undefeated against a schedule of semipro and amateur teams. They still remain as baseball's only undefeated team during the regular season. [26] The first professional league, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, lasted from 1871 to 1875; scholars dispute its status as a major league.[27]

The more formally structured National League was founded in 1876. As the oldest surviving major league, the National League is sometimes referred to as the "senior circuit."[28] Several other major leagues formed and failed. In 1884, African American Moses Walker (and, briefly, his brother Welday) played in one of these, the American Association.[29] An injury ended Walker's major league career, and by the early 1890s, a gentlemen's agreement in the form of the baseball color line effectively barred black players from the white-owned professional leagues, major and minor.[30] Professional Negro leagues formed, but quickly folded. Several independent African American teams succeeded as barnstormers.[31] Also in 1884, overhand pitching was legalized.[32] In 1887, softball, under the name of indoor baseball or indoor-outdoor, was invented as a winter version of the parent game.[33] Virtually all of the modern baseball rules were in place by 1893; the last major change—counting foul balls as strikes—was instituted in 1901.[32] The National League's first successful counterpart, the American League, which evolved from the minor Western League, was established that year.[34] The two leagues, each with eight teams, were rivals that fought for the best players, often disregarding each other's contracts and engaging in bitter legal disputes.[35]

_(LOC).jpg)

A modicum of peace was eventually established, leading to the National Agreement of 1903. The pact formalized relations both between the two major leagues and between them and the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues, representing most of the country's minor professional leagues.[36] The World Series, pitting the two major league champions against each other, was inaugurated that fall, albeit without express major league sanction: The Boston Americans of the American League defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates of the National League.[37] The next year, the series was not held, as the National League champion New York Giants, under manager John McGraw, refused to recognize the major league status of the American League and its champion.[38] In 1905, the Giants were National League champions again and team management relented, leading to the establishment of the World Series as the major leagues' annual championship event.[39]

As professional baseball became increasingly profitable, players frequently raised grievances against owners over issues of control and equitable income distribution. During the major leagues' early decades, players on various teams occasionally attempted strikes, which routinely failed when their jobs were sufficiently threatened. In general, the strict rules of baseball contracts and the reserve clause, which bound players to their teams even when their contracts had ended, tended to keep the players in check.[40] Motivated by dislike for particularly stingy owner Charles Comiskey and gamblers' payoffs, real and promised, members of the Chicago White Sox conspired to throw the 1919 World Series. The Black Sox Scandal led to the formation of a new National Commission of baseball that drew the two major leagues closer together.[41] The first major league baseball commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, was elected in 1920. That year also saw the founding of the Negro National League; the first significant Negro league, it would operate until 1931. For part of the 1920s, it was joined by the Eastern Colored League.[42]

Rise of Ruth and racial integration

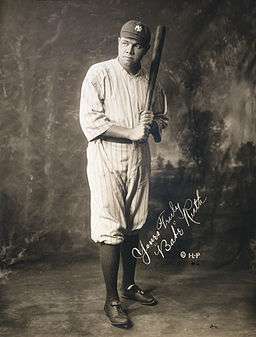

Compared with the present, professional baseball in the early 20th century was lower-scoring, and pitchers, including stars Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson, were more dominant. The "inside game", which demanded that players "scratch for runs", was played much more aggressively than it is today: the brilliant and often violent Ty Cobb epitomized this style.[43] The so-called dead-ball era ended in the early 1920s with several changes in rule and circumstance that were advantageous to hitters. Strict new regulations governing the ball's size, shape and composition, along with a new rule officially banning the spitball and other pitches that depended on the ball being treated or roughed-up with foreign substances, followed the death of Ray Chapman after a pitch struck him in the head in August 1920. Coupled with superior materials available after World War I, this resulted in a ball that traveled farther when hit. The construction of additional seating to accommodate the rising popularity of the game often had the effect of reducing the distance to the outfield fences, making home runs more common.[44] The rise of the legendary player Babe Ruth, the first great power hitter of the new era, helped permanently alter the nature of the game. The club with which Ruth set most of his slugging records, the New York Yankees, built a reputation as the majors' premier team.[45] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, St. Louis Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey invested in several minor league clubs and developed the first modern "farm system".[46] A new Negro National League was organized in 1933; four years later, it was joined by the Negro American League. The first elections to the National Baseball Hall of Fame took place in 1936. In 1939 Little League Baseball was founded in Pennsylvania. By the late 1940s, it was the organizing body for children's baseball leagues across the United States.[47]

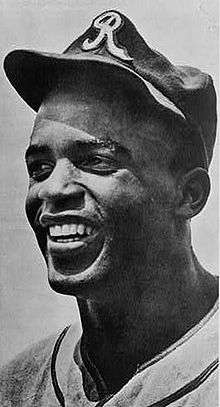

With America's entry into World War II, many professional players had left to serve in the armed forces. A large number of minor league teams disbanded as a result and the major league game seemed under threat as well. Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley led the formation of a new professional league with women players to help keep the game in the public eye—the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League existed from 1943 to 1954.[48] The inaugural College World Series was held in 1947, and the Babe Ruth League youth program was founded. This program soon became another important organizing body for children's baseball. The first crack in the unwritten rules barring blacks from white-controlled professional ball occurred the previous year: Jackie Robinson was signed by the National League's Brooklyn Dodgers—where Branch Rickey had become general manager—and began playing for their minor league team in Montreal.[49] In 1947, Robinson broke the major leagues' color barrier when he debuted with the Dodgers; Larry Doby debuted with the American League's Cleveland Indians later the same year.[50] Latin American players, largely overlooked before, also started entering the majors in greater numbers. In 1951, two Chicago White Sox, Venezuelan-born Chico Carrasquel and black Cuban-born Minnie Miñoso, became the first Hispanic All-Stars.[51][52]

Facing competition as varied as television and football, baseball attendance at all levels declined. While the majors rebounded by the mid-1950s, the minor leagues were gutted and hundreds of semipro and amateur teams dissolved.[53][54] Integration proceeded slowly: by 1953, only six of the 16 major league teams had a black player on the roster.[51] That year, the Major League Baseball Players Association was founded. It was the first professional baseball union to survive more than briefly, but it remained largely ineffective for years.[55] No major league team had been located west of St. Louis until 1958, when the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants relocated to Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively.[56] The majors' final all-white bastion, the Boston Red Sox, added a black player in 1959.[51] With the integration of the majors drying up the available pool of players, the last Negro league folded the following year.[57] In 1961, the American League reached the West Coast with the Los Angeles Angels expansion team, and the major league season was extended from 154 games to 162. This coincidentally helped Roger Maris break Babe Ruth's long-standing single-season home run record, one of the most celebrated marks in baseball.[58] Along with the Angels, three other new franchises were launched during 1961–62. With this, the first major league expansion in 60 years, each league now had ten teams.[59]

Attendance records and the age of steroids

The players' union became bolder under the leadership of former United Steelworkers chief economist and negotiator Marvin Miller, who was elected executive director in 1966.[60] On the playing field, major league pitchers were becoming increasingly dominant again. After the 1968 season, in an effort to restore balance, the strike zone was reduced and the height of the pitcher's mound was lowered from 15 to 10 inches (38.1–25.4 cm). In 1969, both the National and American Leagues added two more expansion teams, the leagues were reorganized into two divisions each, and a post-season playoff system leading to the World Series was instituted. Also that same year, Curt Flood of the St. Louis Cardinals made the first serious legal challenge to the reserve clause. The major leagues' first general players' strike took place in 1972, delaying the season's start for two weeks.[61] In another effort to add more offense to the game, the American League adopted the designated hitter rule the following year.[62] In 1975, the union's power—and players' salaries—began to increase greatly when the reserve clause was effectively struck down, leading to the free agency system.[63] In 1977, two more expansion teams joined the American League. Significant work stoppages occurred again in 1981 and 1994, the latter forcing the cancellation of the World Series for the first time in 90 years.[64] Attendance had been growing steadily since the mid-1970s and in 1994, before the stoppage, the majors were setting their all-time record for per-game attendance.[54][65]

The addition of two more expansion teams after the 1993 season had facilitated another restructuring of the major leagues, this time into three divisions each. Offensive production—the number of home runs in particular—had surged that year, and again in the abbreviated 1994 season.[66] After play resumed in 1995, this trend continued and non-division-winning wild card teams became a permanent fixture of the post-season. Regular-season interleague play was introduced in 1997 and the second-highest attendance mark for a full season was set.[67] The next year, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa both surpassed Maris's decades-old single-season home run record, and two more expansion franchises were added. In 2000, the National and American Leagues were dissolved as legal entities. While their identities were maintained for scheduling purposes (and the designated hitter distinction), the regulations and other functions—such as player discipline and umpire supervision—they had administered separately were consolidated under the rubric of Major League Baseball (MLB).[68]

In 2001, Barry Bonds established the current record of 73 home runs in a single season. There had long been suspicions that the dramatic increase in power hitting was fueled in large part by the abuse of illegal steroids (as well as by the dilution of pitching talent due to expansion), but the issue only began attracting significant media attention in 2002 and there was no penalty for the use of performance-enhancing drugs before 2004.[69] In 2007, Bonds became MLB's all-time home run leader, surpassing Hank Aaron, as total major league and minor league attendance both reached all-time highs.[70][71] Even though McGwire, Sosa, and Bonds—as well as many other players, including storied pitcher Roger Clemens—have been implicated in the steroid abuse scandal, their feats and those of other sluggers had become the major leagues' defining attraction.[72] In contrast to the professional game's resurgence in popularity after the 1994 interruption, Little League enrollment was in decline: after peaking in 1996, it dropped 1 percent a year over the following decade.[73] With more rigorous testing and penalties for performance-enhancing drug use a possible factor, the balance between bat and ball swung markedly in 2010, which became known as the "Year of the Pitcher".[74] Runs per game fell to their lowest level in 18 years, and the strikeout rate was higher than it had been in half a century.[75]

Before the start of the 2012 season, MLB altered its rules to double the number of wild card teams admitted into the playoffs to two per league.[76] The playoff expansion resulted in the addition of annual one-game playoffs between the wild card teams in each league.[77]

Around the world

Baseball, widely known as America's pastime, is well established in several other countries as well. The history of baseball in Canada has remained closely linked with that of the sport in the United States. As early as 1877, a professional league, the International Association, featured teams from both countries.[78] While baseball is widely played in Canada and many minor league teams have been based in the country,[79][80] the American major leagues did not include a Canadian club until 1969, when the Montreal Expos joined the National League as an expansion team. In 1977, the expansion Toronto Blue Jays joined the American League. The Blue Jays won the World Series in 1992 and 1993, the first and still the only club from outside the United States to do so. After the 2004 season, Major League Baseball relocated the Expos to Washington, D.C., where the team is now known as the Nationals.[81]

In 1847, American soldiers played what may have been the first baseball game in Mexico at Parque Los Berros in Xalapa, Veracruz. A few days after the Battle of Cerro Gordo, they used the "wooden leg captured (by the Fourth Illinois regiment) from General Santa Anna".[82] The first formal baseball league outside of the United States and Canada was founded in 1878 in Cuba, which maintains a rich baseball tradition and whose national team has been one of the world's strongest since international play began in the late 1930s (all organized baseball in the country has officially been amateur since the Cuban Revolution). The Dominican Republic held its first islandwide championship tournament in 1912.[83] Professional baseball tournaments and leagues began to form in other countries between the world wars, including the Netherlands (formed in 1922), Australia (1934), Japan (1936), Mexico (1937), and Puerto Rico (1938).[84] The Japanese major leagues—the Central League and Pacific League—have long been considered the highest quality professional circuits outside of the United States.[85] Japan has a professional minor league system as well, though it is much smaller than the American version—each team has only one farm club in contrast to MLB teams' four or five.[86]

After World War II, professional leagues were founded in many Latin American countries, most prominently Venezuela (1946) and the Dominican Republic (1955).[87] Since the early 1970s, the annual Caribbean Series has matched the championship clubs from the four leading Latin American winter leagues: the Dominican Professional Baseball League, Mexican Pacific League, Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League, and Venezuelan Professional Baseball League. In Asia, South Korea (1982), Taiwan (1990) and China (2003) all have professional leagues.[88]

Many European countries have professional leagues as well, the most successful, other than the Dutch league, being the Italian league founded in 1948.[89] Compared to those in Asia and Latin America, the various European leagues and the one in Australia historically have had no more than niche appeal. In 2004, Australia won a surprise silver medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics. The Israel Baseball League, launched in 2007, folded after one season.[90] The Confédération Européene de Baseball (European Baseball Confederation), founded in 1953, organizes a number of competitions between clubs from different countries, as well as national squads. Other competitions between national teams, such as the Baseball World Cup and the Olympic baseball tournament, were administered by the International Baseball Federation (IBAF) from its formation in 1938 until its 2013 merger with the International Softball Federation to create the current joint governing body for both sports, the World Baseball Softball Confederation (WBSC). By 2009, the IBAF had 117 member countries.[91] Women's baseball is played on an organized amateur basis in numerous countries.[92] Since 2004, the IBAF and now WBSC have sanctioned the Women's Baseball World Cup, featuring national teams.[93][94]

After being admitted to the Olympics as a medal sport beginning at the 1992 Summer Olympics, baseball was dropped from the 2012 Summer Olympics at the 2005 International Olympic Committee meeting. It remained part of the 2008 Summer Olympics. The elimination of baseball, along with softball, from the 2012 Olympic program enabled the IOC to consider adding two different sports, but none received the votes required for inclusion.[95] While the sport's lack of a following in much of the world was a factor, more important was Major League Baseball's reluctance to have a break during the Games to allow its players to participate, as the National Hockey League now does during the Winter Olympic Games. Such a break is more difficult for MLB to accommodate because it would force the playoffs deeper into cold weather.[96] Seeking reinstatement for the 2016 Summer Olympics, the IBAF proposed an abbreviated competition designed to facilitate the participation of top players, but the effort failed.[97] Major League Baseball initiated the World Baseball Classic, scheduled to precede the major league season, partly as a replacement, high-profile international tournament. The inaugural Classic, held in March 2006, was the first tournament involving national teams to feature a significant number of MLB participants.[98][99] The Baseball World Cup was discontinued after its 2011 edition in favor of an expanded World Baseball Classic.[100]

References

- Block (2005), pp. 106–108.

- Block (2005), pp. 71–72, 75, 89, 147–149, 150, 160, et seq.

- Block (2005), pp. 86, 87, 111–113, 118–121, 135–138, 144, 160; Rader (2008), p. 7.

- Mason, Chris (2009-03-02). "Cricket 'Was Invented in Belgium'". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- "Save rounders! It's the only sport for people who hate sport". The Telegraph. April 6, 2018.

- Block (2005), pp. 139, 140, 151, 164, 178, 179, et seq.; Hellier, Cathy. "Mr. Newbery's Little Pretty Pocket-Book". Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Retrieved 2008-04-12. See Wikisource edition of A Little Pretty Pocket-Book.

- "Why isn't baseball more popular in the UK?". BBC News. 2013-07-26. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- "Major League Baseball Told: Your Sport Is British, Not American". The Daily Telegraph. London. September 11, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Block (2005), pp. 58, 160, 300, 307, 310; Miller, Doug (August 2, 2005). "Pittsfield: Small City, Big Baseball Town". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 21, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Block (2005), pp. 67–75, 181; Gutsmuths quoted: p. 86.

- David Block (2006) “Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game” p. 192. University of Nebraska Press.

- "The Boys Own Book by William Clarke". Maine Historical Society. Retrieved April 6, 2019

- Block (2005), pp. 4–5, 11–15, 25, 33, 59–61, et. seq.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 9–11.

- Block (2005), pp. xiv–xix, 15–18, 32–38, 42–47, et seq.; Rader (2008), pp. 7, 93–94.

- Seymour (1989), pp. 8–9.

- Seymour (1989), p. 9.

- Ryczek, pp. 20–21.

- Sullivan (1997), p. 292.

- Block (2005), p. 84; Koppett (2004), p. 2; Rader (2008), p. 8; Sullivan (1997), p. 10.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 32, 80, 95.

- Tygiel (2000), pp. 8–14; Rader (2008), pp. 71–72.

- Rader (2008), pp. 9, 10.

- Tygiel (2000), p. 6.

- Rader (2008), p. 27; Sullivan (1997), pp. 68, 69.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 43, 73.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 83–87.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 83, 130, 243.

- Zoss (2004), p. 136.

- Zoss (2004), p. 102.

- Sullivan (1997), p. 115.

- Rader (2008), p. 71.

- Heaphy, Leslie, "Women Playing Hardball", in Baseball and Philosophy: Thinking Outside the Batter's Box, ed. Eric Bronson (Open Court, 2004), pp. 246–256 [247]

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 243–246.

- Sullivan (1997), p. 13.

- Rader (2008), p. 110; Zimbalist (2006), p. 22. See "National Agreement for the Government of Professional Base Ball Clubs". roadsidephotos.sabr.org. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 13–16.

- Sullivan (1997), pp. 141–150; Sullivan (1998), pp. 8–10.

- Koppett (2004), p. 99.

- Burk (2001), pp. 56, 100, 102, 103, 113, 143, 147, 170, et seq.; Powers (2003), pp. 17–21, 27, 83, 121, 122, 160–164, 177; Rader (2008), pp. 60–71.

- Powers (2003), pp. 39, 47, 48.

- Burgos (2007), pp. 117, 118.

- Sullivan (1997), p. 214.

- Zoss (2004), p. 90.

- Zoss (2004), p. 192.

- Burk (2001), pp. 34–37.

- "History of Little League". Little League. Archived from the original on 2007-05-14. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- Lesko, Jeneane (2005). "League History". All-American Girls Professional Baseball League Players Association. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- Burgos (2007), p. 158.

- Burgos (2007), pp. 180, 191.

- Powers (2003), p. 111.

- "Baseball: White Sox and Fans Speak Same Language, with a Spanish Accent". The New York Times. October 26, 2005. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Rader (2008), p. 3; Bjarkman (2005), p. xxxvii.

- Simmons, Rob, "The Demand for Spectator Sports", in Handbook on the Economics of Sport, ed. Wladimir Andreff and Stefan Szymanski (Edward Elgar, 2006), pp. 77–89.

- Powers (2003), p. 170.

- Burgos (2007), p. 215.

- Heaphy (2003), pp. 121, 218–224.

- Koppett (2004), pp. 307, 308; Sullivan (2002), pp. 163, 164.

- Blair (2012), pp. 59–61.

- Powers (2003), pp. 170, 172–175.

- Powers (2003), pp. 156–168, 175, 176.

- Sullivan (2002), p. 239.

- Powers (2003), pp. 178, 180, 245.

- Powers (2003), pp. 184–187, 191, 192, 280–282.

- Koppett (2004), pp. 376, 511.

- Rader (2008), pp. 249, 250.

- Koppett (2004), p. 481.

- Koppett (2004), p. 489.

- Rader (2008), pp. 254, 271; Zimbalist (2007), pp. 195, 196; Verducci, Tom (May 29, 2012). "To Cheat or Not to Cheat". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- "MLB Regular-Season Attendance Just Shy of Last Year's Record". Street & Smith's SportsBusiness Daily. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- "Minor League Baseball History". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Powers (2003), pp. 292–293; Rader (2008), pp. 254, 271, 275–277.

- Hilgers, Laura (July 5, 2006). "Youth Sports Drawing More than Ever". CNN. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- Drellich, Evan (October 6, 2010). "Year of the Pitcher Extends to Postseason". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-10. Gregory, Sean (November 2, 2010). "Giants Win World Series: Year of the Pitcher Ends with a Fitting Duel". Time. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- Speier, Alex (October 8, 2010). "Year of the Pitcher, or Year of the Umpire?". WEEI. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- Sheehan, Joe (March 2, 2012). "Additional Wild Cards Won't Solve Problems; They'll Compound Them". SI.com. Retrieved 2012-03-22.

- "Baseball Officially Expands Playoff Format". The New York Times. Associated Press. March 2, 2012. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

- Bjarkman (2004), p. 73; Burk (2001), p. 58.

- "Canada: Baseball participation, popularity rising across the nation". World Baseball Softball Confederation. October 12, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- Flaherty, David H.; Manning, Frank E., eds. (1993). The Beaver Bites Back?: American Popular Culture in Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-0773511200.

- Riess, Steven A. (2015). Sports in America from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 172, 656–657. ISBN 978-1317459477.

- Terry (1909), p. 506.

- Bjarkman (2004), pp. xxiv.

- Bjarkman (2004), pp. xxiv, 11, 123, 137, 233, 356; Gmelch (2006), p. 296.

- McNeil (2000), p. 113.

- Whiting, Robert (April 11, 2007). "Is the MLB Destroying Japan's National Pastime?". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- Bjarkman (2004), pp. xxiv, xxv; Burgos (2007), p. 46.

- Bjarkman (2004), pp. 362, 368; Gmelch (2006), pp. 100, 75, 59.

- Bjarkman (2004), p. xv.

- Mayo, Jonathan (January 28, 2009). "Perspective: Baseball in the Holy Land". Minor League Baseball. Archived from the original on January 31, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "International Baseball Federation (Confederations/Member Federations)". International Baseball Federation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Seymour Mills, Dorothy (2009). Chasing Baseball: Our Obsession with its History, Numbers, People and Places. McFarland & Company. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0786455881.

- "A Highlighted History of Women in Baseball". USA Baseball. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Berman, Dave (February 21, 2018). "World's women's baseball elite coming to Viera for 12-team World Cup in August". Florida Today. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- "Fewer Sports for London Olympics". BBC News. July 8, 2005. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- McCauley, Janie (August 23, 2008). "MLB Wants Baseball Back in Olympics". The Washington Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- Wilson, Stephen (August 13, 2009). "Softball Again Misses the Cut for Olympic Games". Associated Press (USA Today). Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- Isidore, Chris (March 11, 2006). "The Spring Classic?". CNNMoney.com. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- McNeal, Stan (March 3, 2006). "Your Guide to the '06 World Baseball Classic". Sporting News. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved 2009-02-03 – via HighBeam.

- "IBAF Congress Approves New Format of International Tournaments" (Press release). International Baseball Federation. December 3, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

Sources

- Bjarkman, Peter C. (2004). Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-32268-6. OCLC 58806121.

- Blair, Roger D. (2012). Sports Economics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87661-2. OCLC 898662502.

- Block, David (2005). Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6255-8. OCLC 70261798.

- Burgos, Adrian (2007). Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25143-1. OCLC 81150202.

- Burk, Robert F. (2001). Never Just a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball to 1920. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4961-8. OCLC 28183874.

- Gmelch, George (2006). Baseball Without Borders: The International Pastime. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7125-5. OCLC 64594333.

- Heaphy, Leslie A. (2003). The Negro Leagues, 1869–1960. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1380-8. OCLC 50285143.

- Koppett, Leonard (2004). Koppett's Concise History of Major League Baseball. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1286-4. OCLC 54674804.

- McNeil, William (2000). Baseball's Other All-Stars: The Greatest Players from the Negro Leagues, the Japanese Leagues, the Mexican League, and the Pre-1960 Winter Leagues in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0784-0. OCLC 42976826.

- Powers, Albert Theodore (2003). The Business of Baseball. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1426-X. OCLC 50866929.

- Rader, Benjamin G. (2008). Baseball: A History of America's Game (3rd ed.). University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07550-1. OCLC 176980876.

- Riess, Steven A. (1991). City Games: The Evolution of American Urban Society and the Rise of Sports. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06216-7. OCLC 23739530.

- Ryczek, William J. (2009). Baseball's First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-4194-5.

- Seymour, Harold (1989). Baseball: The Early Years. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503890-3.

- Sullivan, Dean (ed.) (1997). Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825–1908. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9244-9. OCLC 36258074.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sullivan, Dean (ed.) (1998). Middle Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1900–1948. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4258-1. OCLC 37533976.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sullivan, Dean (ed.) (2002). Late Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1945–1972. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9285-6. OCLC 47643746.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Terry, Thomas Philip (1911). Terry's Mexico: Handbook for Travellers (2nd rev. ed.). Gay and Hancock, Houghton Mifflin, and Sonora News. OCLC 7587420.

- Tygiel, Jules (2000). Past Time: Baseball as History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508958-8. OCLC 42290019.

- Zimbalist, Andrew (2007). In the Best Interests of Baseball?: The Revolutionary Reign of Bud Selig. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-12824-0. OCLC 62796332.

- Zoss, Joel (2004). Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9920-6. OCLC 54611393.