History of Rijeka

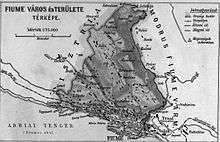

Rijeka, formerly known as Fiume, is a city located in the northern tip of the Kvarner Gulf in the northern Adriatic. It was part of the Roman province of Dalmatia, and later of the Kingdom of Croatia. It grew during the 12th to 14th centuries as a seaport within the Holy Roman Empire, trading with Italian cities. Under the ownership of the House of Habsburg from 1466, it was made a free city, and although part of the Duchy of Carniola it developed organs of local self-government.

During the 16th and 17th centuries Rijeka came under attack from both Turkish and Venetian forces, and became a base for irregular Habsburg troops known as Uskoks. Its maritime trade was suppressed by Venice until the late 17th century, when peace was concluded and the Habsburgs set about developing the city as a major port. Sugar refineries and other industries were also introduced. Rijeka was attached to the Kingdom of Hungary in 1779, retaining autonomous status, although the Kingdom of Croatia also maintained a claim.

Rijeka was occupied by Napoleonic France between 1809 and 1813 as part of the Illyrian Provinces. After reconquest by Austria, it was placed within the Kingdom of Illyria until 1822 and then restored to Hungary. Industrial development recommenced, the port was modernised and a naval base created, and railways were constructed connecting the city with Hungary and Serbia. On the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Hungary gained equal status with Austria, and Rijeka, as Hungary's main port, became a rival to Austria's port of Trieste. Under the leadership of Giovanni de Ciotta the city was extensively rebuilt during the late 19th century. Resulting from further industrial expansion and immigration, Italians became the largest single group in the city.

On the defeat and dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in 1918, Italy and the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) both laid claim to Rijeka. Negotiations in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference were pre-empted by the coup led by Gabriele D'Annunzio, setting up the Italian Regency of Carnaro based in the city. This was suppressed by Italian troops the next year, and under the Treaty of Rapallo the independent Free State of Fiume was established. However, after Benito Mussolini became ruler in Italy, Rijeka (as Fiume) was annexed to Italy in 1924.

Rijeka was occupied by German troops in 1943 after Italy came to terms with the Allies of World War II, and experienced extensive damage from Allied bombing. After fierce fighting it was captured on 3 May 1945 by Yugoslav forces and annexed to the Socialist Republic of Croatia under the Paris peace treaty of 1947. Most of the Italian population fled or were removed, and were subsequently replaced by incomers from other parts of Yugoslavia. Rijeka became the largest port in Yugoslavia, and other growth sectors included port traffic, oil and coal. On the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, Rijeka became part of independent Croatia, but has experienced economic difficulties with the closure of many of its older industries.

Origins

The region of Quarnero (Fiume was still not mentioned) fell within the Holy Roman Empire, with the acquisition of the titles of Margraves of Istria and Dukes of Merania by the Andechs family. The possession was called Merania (German: meer – "sea") meaning "littoral" (German: Küstenland).

The counts of Duino (Tibein), were the first feudal lords of Fiume, from the early 12th century until 1337. As ministeriales of the Patriarchate of Aquileia, the family proved crucial in extending German control preventing further expansion of the Republic of Venice on the northernmost Adriatic. The counts of Duino included the city into a comparatively good road network, which were in operation on the routes leading towards the sea. The Fiuman Terra was their most important fief, that with its possession controlled a good road network from the river Timavo to the Quarnero gulf. Along these roads, marked by several castles and outposts (Senožeče, Gotnik (Guettenegg) and Prem) guarding the land communications from the Quarnero towards Carniola, the contemporary Slovenia. Traders are reported from Carinthian Villach, Carniolan Ljubljana (Laibach) and Styrian Ptuj (Pettau) but also from the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire.

In Fiume the local toponymy is predominantly Slavic Croatian, Italians came from the sea, usually as craftsmen and traders, from the central Italian Adriatic ports, such as Fermo, Ancona, Senigallia, and with Venice. The trade of Fiume develops in linking the German lands with central Italian ports. Notably, the contacts with Croatia were very scarce given the absence of land connections of Fiume with its eastern hinterland.

In 1399, the territory fell into the hands of the German family of Walsee, the last of whom sold the territory to the Habsburgs in 1465. After the extinction of the house of the Walsee in 1465, the possessions were inherited by the Habsburg family that owned it from 1466 to 1776. The Habsburgs granted Fiume with the status of a free city, and included in the Duchy of Carniola.

As a reichsfrei city, or territory (Fiume was a terra) was under the direct authority of the Holy Roman Emperor and the Imperial Diet, without any intermediary liege lord(s). Advantages were that reichsfrei regions had the right to collect taxes and tolls themselves, and held juridical rights themselves. De facto imperial immediacy corresponded to a semi-independence with a far-reaching autonomy. In 1599 Fiume de facto becomes an independent City commune, emancipated from the Duchy of Carniola, although the Carniolan Estates continued (unsuccessfully) to claim their rights upon the city – right up to their cessation in 1809.

The late mediaeval Commune was ruled according to the Statute from 1530 but this charter formally lasted until 1850. The first codified Statute of Fiume preserves some features of the mediaeval Croatian statutes, still with a preponderance of Italian and Venetian institutions. According to the Statute, the executive power was in the hand of the Gran Consiglio ("Great council") with 50 members and the Piccolo Consiglio ("Small council") of 25 patricians. The Captain was the representative of the feudal lord (from 1466 the Habsburg archduke). The local executives, giudici rettori ("justice rectors"), have to obey only the lord – from 1466 the duke (later Emperor) of the House of Habsburg. Thus, in its local corporate representation Fiume was a mixture between the local self-government tradition and the Reichsfreiheit or Reichsunmittelbarkeit of the free cities of the Holy Roman Empire.

Turkish wars

Fiume by the 19th century had arisen as the most important port for the eastern half of the Habsburg empire, but its beginnings are modest: at the dawn of the modern age it was still a small port city, with less than 5000 inhabitants. The Kingdom of Croatia, with whom the city bordered along the eastern shores of its river, merged with the Kingdom of Hungary, after the disaster of the Battle of Mohács in 1526. Both kingdoms accepted the sovereignty of the Habsburgs to defend from the Turkish conquests. Following 1526, the stretch of territory south of Fiume and north of the Zrmanja river (called the Littoral) was held by the House of Austria – inheritor of the Crowns of Croatia and Hungary. Southwards, Venetian Dalmatia spread up to Cattaro. As such these lands were permanently put on a frontline, intended to bring to a halt the Ottoman advance that stopped short of the gulf of Quarnero.

Until the late 17th century, the Habsburg monarchy was essentially a landlocked territory: trade and traffic had followed the commercial routes to the North and Northwest, and Hamburg was the main port for Austrian products. When these routes became increasingly blocked by the growing Prussian state, the Monarchy started to turn towards its southern possessions. The trade of the City still languished since the Habsburgs retraced to Trieste all the Austrian exports, also because of the insecurity of land communications thorough Fiume.

Turkish attacks and intrusion in Croatia and the surroundings of Fiume, were particularly frequent from 1469 to 1502, helped by the near absence of any organised defence. The threat from the Ottoman Empire which kept the monarchy engaged in permanent military actions and in concluding coalitions with Christian allies and Venice was one of these. The northern Adriatic thus functioned as something as an Ottoman, Venetian, and Habsburg borderland's littoral.

The border itself was a very fuzzy and mobile concept in the region for centuries: the Croatian Littoral and its hinterland were an integrated part of the Habsburg Military Frontier which was more than a defensive institution and marked all the stages of societal development in the area. Its principal characteristic was that the various fortresses were manned with regular and irregular troops for a permanent low intensity warfare which included raiding as its main source of revenues. Incursions of armed bands both form the Ottoman side the irregular Hajduks and Uskoks as well as the local Military Frontier troops (Grenzer) were conducted on a daily basis.

Probably no phenomenon describes the turbulent events in the area better than the rise of the Uskok's piracy and banditry in the northern Adriatic. Uskoks served as irregulars in the Habsburg border garrison of Senj for a century. The Habsburg and the Pope celebrated their role as bulwark of Christendom, while for the Venetians (laics and priests alike) they were "bandits and pirates worse than the Turks and responsible for innumerable atrocities". Fiume's history is very much that of the Uskoks for much of the 16th century. In fact the City survived as a port of trade principally thanks to afflux of the merchandise they robbed. It was a world of precarious life and insecurity where trade degenerated into a raiding economy. Venetia, knowing that the Uskoks had Fiume as their main "emporium", sacked and burned the City in 1530 in a punitive expedition. Uskok piracy aroused as a serious diplomatic problem between Austria and Venetia and was settled in 1612 with the Treaty of Vienna with whom the Emperor refused any support to the Uskoks.

The repeated attempts of Habsburg emperors to expand and enlarge the tiny fishing villages of the northern Adriatic into functioning ports had previously failed because of the domination of Venice that controlled the entire Adriatic and fiercely opposed the development of the Habsburg ports. Even that did not prevent a series of Venetian occupations and destruction of Fiume, from 1508 to 1512, 1530, 1599 and, finally, in 1612. The maritime traffic was reduced to cabotage, since the Serenissima controlled all ships leaving the ports. Habsburg emperors unsuccessfully tried to break this domination of the sea, claiming free shipping for all and formulating it in treaties and diplomatic agreements.

Only with the pacification of the Turks, which seemed realisable for the first time at the end of the 17th century, could new attempts be undertaken. At the end of the 17th century the Ottomans are defeated and with the Treaty of Karlovitz (1699) the Empire regains control over the vast plains of Vojvodina and Banat promptly put under the direct control of the Imperial Chamber (Kaiserliche Hofkammer) of Inner Austria with seat in Graz as the Imperial Regency, to finance the military needs against the Ottomans.

The origins of the emporium

The origins of the emporium are to be located in the late 17th century when a mercantilist program starts to find its way into the Habsburg lands. Already in year 1666, under Emperor Leopold I, in Vienna a Commerzcollegium was founded, an office with the main function of initiating some economic reforms and the control of their execution. Based upon mercantilistic principles, a homogeneous "Littoral district" was to be created along the Adriatic coast.

Besides the local and, up to that time, unimportant ports of Trieste and Fiume, the plan also encompassed the integration of Croatian territories, which had been seized from the Ottoman Empire during the second half of the 17th century: the Gulf of Bakar, Senj and Karlobag where the Habsburgs met the competition of the local powerful landlords who started to develop as ports some of the coastal towns they owned. The Zrinski (Zriny) were the most powerful landowners in Croatia and most of the land that surrounded Fiume (as well as the city of Bakar (Buccari) was in their hands. They developed the port of Buccari, the best natural harbour in the area, comparatively well connected with the hinterland. Alliance with Venice and much lower taxes explain the success of Buccari, where soon the rise in traffic vastly outnumbered that of the Habsburg port of Fiume. Buccari had a lazaretto, founded by a Venetian company. The other family were the Frankopan (Frangipane) who owned and developed the port of Kraljevica (Portorè). These developments came to an abrupt end with the Zrinski-Frankopan conspiracy. After the end of the rebellion in 1673, that resulted in their defeat all these possessions were confiscated and put under the control of the Hungarian Aulic Chamber, soon transferred to the Imperial Chamber of Inner Austria. The destruction of the most powerful feudal families and their economic might ensured that no similar event would take place during the feudal era. Between Vienna and the Adriatic ports there were no feudal lords capable of competing or disturbing the plans of economic development. One of the big obstacles for the implementation of these policies was the Venetian monopoly on the Adriatic which effectively prevented ships form other countries to fare freely on this closed sea at the time known also as the "Gulf of Venice". Success was achieved under Charles VI. In 1717 after another victorious campaign against the Ottomans (but this time with Venice as its ally) the Adriatic sea was promptly declared free for trade, with Venice no longer opposing it; in 1718 peace was concluded with the Ottoman Empire and a commercial treaty brought important commercial liberties to the Ottoman and Habsburg subjects; in 1719 Trieste and Fiume were declared Free Ports of the Empire of the Habsburgs.

In 1723 the "Gran Consiglio" of the Fiuman commune was put under the Circle of Inner Austria with the seat in Graz. The Captain as a representative of the Emperor still held the executive power for the governmental economic policy. Progressively, Fiume was included in broader institutional frameworks, aimed at economic development of the whole empire, but growingly of its Hungarian part. That Hungarian influence was on the rise is reflected also in fact that Fiume, as a Free City, accepted the Pragmatic Sanction, in 1723 – the same year as the Hungarian Diet, while the "sister city" of Trieste did it ten year earlier in 1713 - as the other Habsburg lands. Trieste was intended in Charles VI plans to link Austrian lands with his remaining Spanish possessions – Naples. Fiume had to provide a link with Hungary and the Banat of Temesvar where the colony of Spanish exiles of Nova Barcelona was to be founded.[1] The operation was entrusted to Ramon de Vilana Perlas Marques de Rialp (1663-1741), Spanish Secretary of State to Emperor Charles VI, who until his resignation in 1737 was secretario de estado y de despacho – the executive of the Spanish and Belgian councils and coordinated diplomatic relations involving the Emperor's Italian and Belgian outposts.[2] The project failed, but links of Fiume with the Banat of Temesvar remained strong.[3] Under the reign of Maria Theresa (1740–1780), in 1741 in Vienna is formed the Comercien Ober Directorium upon which all the commercial affairs of the empire is centred. In 1745 she united the administrations of all the ports within an Oberste Commerz-Intendenza (High Commercial Intendancy), which was originally established by her father in 1731.

Fiume, instead of a Kreisamt, subordinated to the Gubernium, has a Direzione Superiore Commerciale (Kommerzassesorium) subordinated to the Cesarea Regia Intendenza Commerciale per il Litorale, seated in Trieste. The Intendenza was the first provincial imperial institution that ruled the City from 1748 until 1776. In 1749 Maria Theresa issued the Haupt Resolution by which the civil and military Capitan of Trieste was put under the control of the Comercien Ober Directorium seated in Vienna. All the region of the Littoral in fact became a territorial dependency of this new institution, specifically oriented to the development of commerce and thus very different from the other (still feudal) provinces. From 1753 the Intendenza Capitanale di Fiume Tersatto e Buccari, executed the orders from the head office in Trieste. The Fiuman "Luogotenente" of the Cesarea Regia Luogotenenza Governale del Capitanato di Fiume, Tersatto e Buccari, had also the role of the previous captain, and his jurisdiction extended from Moschienizze to Carlopago. The Intendenza transmits the orders to the Justice Rectors in Fiume. Thereby the autonomy of the local institutions (the Justice Rectors previously were at the top of the communal administration) was gradually reduced.

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor also founded a "privileged company" in Fiume. The purpose of these measures was to attract foreign investments, but the first companies were controlled from the chamber in Vienna and went bankrupt. The turn came in 1750, with the foundation of the Urban Arnold & Co. company, with the seat in Antwerp. Initially it dealt with the refinement of sugar, and the production of potash and tallow candles. It also possessed its own port basin and the number of its sugar refining plants grew from one to five. Soon, already in 1754, the Company was supplying the while monarchy with sugar that became its main traded article. The company was bigger than anything Fiume had previously seen. It employed more than 1000 workers and employees in a time when the city had little more than 5000 inhabitants. Apart from sugar the company produced salted meat. The company bring new life to Fiuman economy and started many spin-offs (candle and rope factories, etc.). Industrial production in the city rose rapidly: in 1771 it was valued at 802,582 guldens, in 1780 2,278,000. the value of imports in 1771 was 1,187,000 guldens, in 1780 2,781,000 guldens. Exports value in 1771 was 496,000 guldens, in 1780 1,340,000 guldens, but probably they were even higher: according to the Ragusan diplomat Luka Sorkočević who in 1782 stayed in Fiume in his private diary estimated the added value of the fiuman economy (based on the value of its exported goods) at 2,5 million guldens.

Corpus Separatum

During the 1740s most of the trade from the Pannonian plain was starting to pass over Fiume and not Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which after the retreat of the Ottoman Empire, never regained the lost ground. After a series of formal acts of protest of the Hungarian and Croat Landed Estates, Joseph II during his journey through Croatia, the Littoral and Venice in 1775, which was carried out one year later, in 1776, decided the abolition of the ‘Litorale Austriaco’. In the same year the "Provincia Mercantile" was suspended. In 1776, the City of Fiume and the Croatian seaboard, which had previously been under the same administration as the rest of the Austrian littoral, is annexed to the Kingdom of Croatia, with a Maria Theresa Handschrift. The Empress donated these lands and possessions to Croatia – Hungary as a compensation since many of their lands were put under the direct imperial administration as the osterreichische Militargrenze (Military Frontier) against the Turks, exclusively for defensive purposes.

Maria Theresa, with her sovereign decision from October the 2nd 1776, gave up the possession of Fiume, that so far belonged to the Habsburgs, and give it to the Hungarian kingdom, with a view of fostering its trade. Since Hungary proper was distant some 500 km, according to the act, understandably, the city was annexed to Croatia whose territory began right beyond the city walls. Although Croatia, as a kingdom, was united with Hungary and together they formed the "Lands of the Holy Crown of St Stephen", the Fiumani protested, and with support of the Hungarian Vice Regency Council, two and a half years later, Maria Theresa (as Queen of Hungary) enacted the royal rescript on April, the 23rd 1779, with whom Fiume was annexed to Hungary directly as a corpus separatum adnexum sacra hungaricae coronae. From that moment on the two kingdoms never ceased to batter on the issue whose was Fiume. The Fiumani, as a third part, gave their reading that Fiume (or better: the corpus separatum) was autonomous from both. Given the institutional instability that characterized the whole period from 1779 up to 1848, this was more or less true. Fiume retained the autonomous status from the surrounding territory it enjoyed with the Habsburgs, since the function of the Governor was preserved, and who was now always drawn from the ranks of the Hungarian aristocracy. Fiume was the only city in Hungary (Croatia included) that had such an institution. The development of the port needed huge investments that only Hungary could offer and the leaning of all the local forces towards Hungary appears inevitable.

The Gubernium of Fiume

The territory was to form the new comitatus of Severin that also included all the confiscated possessions of the Frangipane and Zrinski families that surrounded Fiume in the interior. Trieste now became the only harbour of the German hereditary lands. Fiume became fully independent from Trieste in all-commercial, fiscal and administrative matters as the main port of Hungary, which meant excluding the city from the Holy Roman Empire, and here a Gubernium was installed too, while the other ports were annexed to Croatia.

The inclusion of Fiume into Croatia arouse a series of protests from the fiuman notables, promptly supported by the Hungarian estates. In fact already in 1776, when it was decreed to include Fiume to Hungary through Croatia, it was the count József Majláth, acting as Hungarian royal commissar, who took over the town from baron Pasquale Ricci, the representative of the Intendancy from Trieste.

Shortly after that, (with the rescript of the queen dated 23 April 1779) the City is officially directly annexed to Hungary as a corpus separatum) (i.e.: not as a part of Croatia, that was in a personal union with Hungary). Since Fiume had to serve a similar "emporial" function for Hungary as Trieste did for the Habsburg lands, the Hungarian estates (and most probably the Queen) wanted to grant the City a similar degree of institutional autonomy as that enjoyed by Trieste.

According to the rescript from 1779, Fiume was considered to be a corpus separatum – that is a political body with a greater autonomy than a royal free City, or a comitatus, but a territory comparable to the other partes adnexae constituting the Crown of the St. Stephen. Its position was thus comparable to those of the regna, as Trieste was considered to be a crown land of the Habsburg hereditary lands (Erblande) so Fiume was considered to be a partes adnexa to the crown. After the royal rescript from 23 April 1779, the stage for all the political confrontations that will happen in Fiume was set for more than a century and a half. In a sense it can be said that all history that followed was a long footnote on how to interpret this two acts from 1776 and 1779. The act presented a precedent for the Hungarian constitutional praxis, since it was the first time that a part of the Holy Roman Empire (and a hereditary fief of the Habsburgs) was given to the Hungarian-Croatian kingdom. Therefore, since the Croatian and Hungarian estates had widely diverging interests with respect to Fiume, they produced very different interpretations of the rescript.

The Croatians refused to accept the Hungarian reading of the document – they denied that the City could have been excluded from the surrounding territory, that was already framed into a comitatus. Since the Croatian estates never accepted this interpretation, the constitutional position of the City was always somehow imprecise. On the other hand, the change happened when the Croatian diet voted for the suspension of the short-lived Croatian Vice-regency Council in Vienna whose prerogatives were now entirely devolved to the Hungarian Vice-regency Council, now the supreme administrative authority for Croatia as well.

Fiume becomes the administrative centre for two very different – and overlapping – administrative units: The Gubernium of Fiume and the Comitatus of Severin (Severinska Županija), that is an integral part of Croatia. Arguably the simultaneous existence of the two competing offices reflects the still unsettled dispute between the Hungarian and the Croat estates. The predictable outcome of this clash came in 1787, when Joseph II dissolved the County of Severin confirming its transitory nature and introduces a new province (instead of a constituted comitatus of nobles): The "Hungarian Littoral" which now extends from Fiume to Senj. And in Fiume the "Cesareo Regio Governatorato per il Litorale in Fiume" governs the whole new province of the "Hungarian Littoral" (Litorale ungarico), thereby eliminating the Croatian competencies in this stretch of land. For the first time in 1790, unofficially, the representatives of Fiume took part at the gathering of the Hungarian parliament. They claimed the annexation to Hungary, but it was postponed three times by the Habsburg monarchs in 1790, 1802, and 1805. Finally, in 1807, Fiume became legally a part of Hungary. The Fiuman governor had a right to vote in the Chamber of Magnates of the Royal Hungarian Diet (Orszaggyules), while "the deputies of Fiume" (probably two, since their number was still not specified by the law) had the right to vote as members of the Stände und Orden. Fiume become part of the Hungarian Orszag, but de facto the law was never applied.

Judicial system – Fiume (1790s)

The Gubernium of Fiume is now under the direct Hungarian administration in terms of commercial and economic policies, but still the comitatus of Zagreb retains competencies in judiciary and public education matters. But these capacities were insignificant since in Fiume higher education, initially set by the Jesuits in the 17th century, was replaced by Hungarians after the suppression of the order. On the other hand, in Fiume the judiciary competencies were retained by the local patricians, and de facto, the comitatus of Zagreb and the Croatian estates in Fiume were powerless, since the Gubernium acted as a Court of Appeal (Capitanale Consiglio e Sede Criminale) both for the commercial and civil courts in Fiume.

| Judicial system – Fiume (1790s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Illyrian Provinces (1809–1813)

The stability that should have followed the law from 1807 wasn't about to last long: the decade after the French revolution witnessed a series of wars with which the Habsburgs will always be involved. After two brief occupations in 1797 and 1805, a French government was introduced in 1809, with Fiume included in the "Illyrian provinces" with the seat in Ljubljana. The City constitutes a special "District of Fiume" within Civil Croatia with 3 districts Karlovac, Fiume, Senj with the seat in Karlovac.[4]

The French were to make of the Illyrian provinces a bridge to the oriental traffic so there was a considerable rise of the land-based traffic with the Levant. The British Navy imposed a blockade of the Adriatic Sea, effective since the Treaty of Tilsit (July 1807), which brought merchant shipping to a standstill, a measure most seriously affecting the economy of the Dalmatian port cities. The English with their base on the island of Lissa, soon become masters of the Adriatic. An attempt by joint French and Italian forces to seize the British-held Dalmatian island of Vis failed on 22 October 1810. Napoleon's exclusively land-based customs enforcers could not stop British smugglers, especially as these operated with the connivance of Napoleon's chosen rulers of Spain, Westphalia and other German states, who faced severe shortages of goods from the French colonies. The embargo encouraged British merchants to aggressively seek out new markets and to engage in smuggling with continental Europe. In Fiume Andrea Lodovico de Adamich emerged to become the wealthiest and most powerful merchant in Fiume.[5]

In August 1813, Austria declared war on France. Austrian troops led by General Franz Tomassich invaded the Illyrian provinces. Croat troops enrolled in the French army switched sides. The English General Nugent, serving the Austrian Empire, liberated the town from the reign of the "Illyrian passing glory" on 26 August 1813.[6]

Restoration (1814–1848)

Vienna was reluctant to reincorporate "Transsavan Croatia" (or "Illyrian Croatia") probably because of Metternich's policy towards the region.[7] In the Restoration 1814-1822 Fiume was put under the ephemeral "Kingdom of Illyria". By the end of the Austrian reign (1823), including the first Hungarian period too (1776–1809), Fiume hardly developed; only minor constructions were done. The number of the inhabitants shows slow increase: in 1777 the number of population was 5312, in 1819 it was 8345.

Francis I, with the order of 1 June 1822, gave back Fiume to Hungary to form the centre of the Hungarial Littoral (Littorale Hungaricum) with the by-ports of Buccari, Portoré and Novi. The new Hungarian governor, Antal Majláth (son of József Majláth, the first Hungarian governor in Fiume) took over the duty on 15 October 1822. Emperor Francis, with a rescript in 1822, made autonomous the Kreise of Carlstadt and Fiume, and thereby, in November 1822, restored the Comitatus of Severin.[8]

Fiume was invited to participate also to the Croatian Diet in Zagreb, where Antun Mihanović then employed as a gubernial secretary was sent. In 1825 – 26 Antun Mihanović (1796-1861) and Andrea Lodovico Adamich (1766–1828) participated at the workings of the Hungarian Diet in Presburg. Adamich there tried to promote a project for a Hungarian commercial company centred in Fiume circulating a memo (eszrevetelek) with scarce success. Afterwards he served as mercantile deputy of Fiume from 1827 until his death in 1828.[9]

Fiuman deputies participated also in the role of observes to the Croatian diets of 1830 and 1832. Far more important was the Hungarian diets from 1832 to 1836 that started the period of liberal reforms in Hungary. With the article XIX of the Hungarian law of 1836 the Fiuman judiciary was firmly included into the Hungarian judicial system and the local civic magistrate lost his judicial capacities transferred to a local court, the Giudizio Civico Distrettuale della fedelissima Città, Porto franco e Distretto di Fiume.

After the governorship of Ferencz Ürményi (1780 - 1858, governor from 1823 to 1837) Pál Kiss de Nemskér became new governor while Count Ferenc Zichy (1811–1900) acted as deputy governor and was to become Hungarian secretary of state for commerce in the Széchenyi ministry of 1848. After the death of Adamich, Cimiotti become deputy of Fiume at the royal Hungarian Diet serving in 1836 first as observer, and then taking active part in 1843/4. One of his first task as a deputy, together with Mihály Horhy was to draft a plan for political modernization of Fiume, preserving its autonomy within the Hungarian political system. After the inclusion of the city in the Hungarian system Cimiotti exploited the request (Torvenyjavaslat a Hajdúkerületrol 1843/4) advanced by the Hajdú County (Hajdúság) who constituted a "warrior estate" within Hungarian feudal society and were emancipated by István Bocskay, Lord of Bihar, in 1604-1606 from the jurisdiction of their lords. As the Hajdú, Jász and Cuman districts were freed of feudal obligations providing military service so Fiume had to be exempted by providing maritime service for the Kingdom of Hungary. Cimiotti took also the privileges granted to the Gölnicbánya (German: Göllnitz) miners who, as Bavarian settlers invited by the king of Hungary were granted special privileges.[10]

Industrial revolution was well under way: already in 1827 the Smith & Meynier paper mill was founded. In order to get support for the modernization of the port, the "Mercantile deputation" of Fiume sent Ferenc Császár to lobby at the Pest Exchange court in 1842. In 1843 Josef Bainville a French engineer from Fiume who reproposed an older French plan, commissioned by Adamich during the Illyrian provinces. Bainville settled in Hungary and designed a plan for the city of Szeged. Still in 1842 ambitious plans for advancing trade with Hungary, Wallachia and the Banat were advanced and Cimiotti managed to involve the engineer Mario A. Sanfermo who elaborated a plan to connect Fiume with the Sissek – Carlstadt railroad and its extension to Vukovar and thereby reach Serbia and Wallachia. The railroad Fiume – Vukovar, intended for Russian containment in the context of the Eastern Question, was enthusiastically supported by Kossuth and the founding of a company Vukovar – Fiumana Unitae Societatis Pestano Fluminensis ad construendam semitam ferratam was voted by the Hungarian diet in 1848. In this way the well-known debates of Kossuth and István Széchenyi (who visited Fiume in 1844 and decided to allocate 260,000 guldens for port modernization) about how to build up the railway leading from Central Hungary to Fiume, appeared in Fiume in 1846. In the same year one of the articles of Kossuth, titled To the Sea Hungarians! Go to the Sea! was published in a periodical of the Trade Association.

In 1846 Vincenzo de Domini (1816 - 1903) become professor at the local nautical school. A Venetian patriot, close to the circles of Kossuth, he will be entrusted together with Gaspare Matcovich and Spiridione Gopcevich (1815 - 1861) with the project to turn the brick Implacable into a Hungarian man of war. The armament of the ship, commanded by de Domini, led Jelačić to send an expedition and occupy Fiume on 31 August 1848 with Croat troops.

1848-1870

Hungarian port 1870-1918

Following the creation of Austria-Hungary in the Compromise of 1867, Fiume was attached to Hungary for the third and last time in 1870. Croatia had constitutional autonomy within Hungary, but as Hungary's only international port, the city became an independent corpus separatum, governed directly from Budapest by an appointed governor. Austria's Trieste and Hungary's Fiume competed for maritime trade.

Fiume also had a significant naval base, and in the mid-19th century it became the site of the Austro-Hungarian Naval Academy (K.u.K. Marine-Akademie), where the Austro-Hungarian Navy trained its officers.

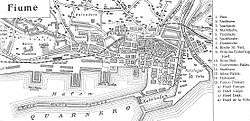

Giovanni de Ciotta (Mayor from 1872 to 1896) proved to be the most authoritative local political leader. Under his leadership, an impressive phase of expansion of the city started, marked by major port development, fueled by the general expansion of international trade and the city's connection (1873) to the Hungarian and Austrian railway networks. Hungarian support proved to be crucial to the development of the port of Fiume and Ciotta was the key person in assuring it. From 1872 to 1896 (apart from a short interruption in 1884) he was the mayor of the city. Following the financial crisis of 1873, that culminated in 1875, the conservative liberal Deák Party had to face a crisis from which it survived only with a merger with the more numerous conservative Left Center of Kálmán Tisza. The "new" Liberal Party of Hungary, was to rule Hungary (and Fiume) from 1875 to 1890, marking the golden years of Ciotta, later known as the Idyll.[11]

Under his lead an impressive phase of expansion of the city started, marked by the completion of the railway Fiume – Budapest, the construction of the modern port and the initiation of modern industrial and commercial enterprises such as the Royal Hungarian Sea Navigation Company "Adria", and the Whitehead Torpedo Works. In 1866, Robert Whitehead, manager of Stabilimento Tecnico Fiumano (an Austrian engineering company engaged in providing engines for the Austro-Hungarian Navy), experimented on the first torpedo. Ciotta's contribution was crucial as he financed Robert Whitehead's efforts in producing a viable torpedo. Modern industrial and commercial enterprises such as the Papermill, situated in the Rječina canyon, producing worldwide known cigarette paper, became trademarks of the city.

The population grew from only 21,000 in 1880 to 50,000 in 1910. A lot of major civic buildings went up at that time, including the Governor's Palace designed by the Hungarian architect Alajos Hauszmann. In 1885 the sumptuous new theatre was finished modelled on that of Budapest and Vienna, costing him a political crisis in 1884 for the raising building costs. While on army service he met John Leard, another fiuman of English origins. Ciotta with Leard in 1889 pushed forward the Piano regolatore the comprehensive urbanisation plan for the city. The new plan laid down the plan for a modern commercial city, destroying most of the older buildings and roads and introducing the regular planning as it was done in Budapest and other cities of the time. In 1891 the Acquedotto Ciotta was finished providing the city with modern sewage and water supply system. He was also a founder of several philanthropic initiatives and institutions.

The "system Ciotta" underwent crisis in 1896 when Hungarian Prime Minister Dezső Bánffy started a centralizing policy towards Fiume. Ciotta, being unable to assure the equilibrium between Fiume and Hungary, resigned and retired to private life, following the Governor Lajos gróf Batthyány de Nemetujvár. As a response Michele Maylender, backed by Luigi Ossoinack (initiator of the Royal Hungarian Sea Navigation Company "Adria"), founded a new party, the Autonomist Association, ending the rule of the Liberal Party of Hungary in Fiume.

The future mayor of New York City, Fiorello La Guardia, lived in the city at the turn of the 20th century, and reportedly even played football for the local sports club.

The Italo-Yugoslav dispute and the Free State

Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary's disintegration in the closing weeks of World War I in the fall of 1918 led to the establishment of rival Croatian and Italian administrations in the city; both Italy and the founders of the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) claimed sovereignty based on their "irredentist" ("unredeemed") ethnic populations.

An international force of Italian, French, Serbian, British and American troops occupied the city (November 1918) while its future was discussed at the Paris Peace Conference during the course of 1919.[12]

Italy based its claim on the fact that Italians were the largest single nationality within the city, 88% of total. Croats made up most of the remainder and were also a majority in the surrounding area, including the neighbouring town of Sušak.[13] Andrea Ossoinack, who had been the last delegate from Fiume to the Hungarian Parliament, was admitted to the conference as a representative of Fiume, and essentially supported the Italian claims.

On 10 September 1919, the Treaty of Saint-Germain was signed declaring the Austro-Hungarian monarchy dissolved. Negotiations over the future of the city were interrupted two days later when a force of Italian nationalist irregulars led by the poet Gabriele d'Annunzio seized control of the city by force; d'Annunzio eventually established a state, the Italian Regency of Carnaro.[14]

The resumption of Italy's premiership by the liberal Giovanni Giolitti in June 1920 signalled a hardening of official attitudes to d'Annunzio's coup. On 12 November, Italy and Yugoslavia concluded the Treaty of Rapallo, under which Rijeka was to be an independent state, the Free State of Fiume, under a regime acceptable to both.[15] D'Annunzio's response was characteristically flamboyant and of doubtful judgment: his declaration of war against Italy invited the bombardment by Italian royal forces which led to his surrender of the city at the end of the year, after a five days resistance. Italian troops took over in January 1921. The election of an autonomist-led constituent assembly for the territory did not put an end to strife: a brief Italian nationalist seizure of power was ended by the intervention of an Italian royal commissioner, and a short-lived local Fascist takeover in March 1922 ended in a third Italian military occupation. Seven months later Italy herself fell under Fascist rule.

Fiume under Fascist rule

A period of diplomatic acrimony closed with the Treaty of Rome (27 January 1924), which assigned Fiume to Italy and Sušak to Yugoslavia, with joint port administration.[16] Formal Italian annexation (16 March 1924) inaugurated twenty years of Italian government, followed by twenty months of German military occupation in World War II. In 1938 Temistocle Testa prefect from Udine become prefect of the Carnaro province.

Rijeka in World War II

_bombing_by_RAF_in_1944.jpg)

After the surrender of Italy to the Allies in September 1943, Rijeka and the surrounding territories were occupied by Germany, becoming part of the Adriatic Littoral Zone. Because of its industries (oil refinery, torpedo factory, shipyards) and its port facilities, the city was a target of frequent Anglo-American air attacks. Some of the worst attacks happened on 12 January 1944 (attack on the refinery, part of the Oil Campaign) , on 3–6 November 1944, when a series of attacks resulted in at least 125 deaths and between 15 and 25 February 1945 (200 dead, 300 wounded).[17] The harbour area was destroyed by retreating German troops at the very end of the war. Yugoslav troops entered the city on 3 May 1945, after heavy fighting.

Post World War II expulsion of Italians

The aftermath of the war saw the city's fate once again resolved by a combination of force and diplomacy. This time, Yugoslav troops advanced (early May 1945) as far west as Trieste in their campaign against the German occupiers of both countries. The city of Rijeka thus became Croatian (i.e., Yugoslav), a situation formalised by the Paris peace treaty between Italy and the wartime Allies on 10 February 1947. Once the change in sovereignty was formalised, 58,000 of the 66,000 Italian-speakers were more or less hastily pushed through various means out of the city (known in Italian as esuli or the exiled ones). The discrimination and persecution many of them experienced at the hands of the Yugoslav officials in the last days of World War II and the first 9 years of peace remained painful memories. Summary executions of alleged fascists (that at times were proven anti-fascists), Italian public servants, military officials and even normal civilians, limited acts of terrorism, imprisonment and loss of work and public positions forced most ethnic Italians to abandon Rijeka in order to avoid further violence. The Trieste crisis in 1954 gave the final pretext to Yugoslav authorities to strip the local Italian-speaking populace of most of its rights (but most were being lost in the years building up to 1954) and enact a more radical and successful assimilation of the previous Italian majority into the new Yugoslav majority.

In Yugoslavia

Because of its importance for the country's shipbuilding industry was from 1947 under the responsibility of the Ministry of National Defence until 1954. In 1948 the main shipyard, renamed Maj 3, which was to serve as a base for the restored shipbuilding industry. In 1949, it launched the first post-war Yugoslav ship, the MB Zagreb of 4000 DWT. Along with the shipbuilding industry would develop one for marine equipment. After being rebuilt, the Torpedo Factory started to produce diesel engines. The former foundry Skull now Svjetlost was devoted to the production of electrical navigation equipment, while the Rikard Benčić manufactured watercraft and other auxiliary equipment. The oil refinery was back in 1948 pre-war production with 110,000 tonnes in the early Fifties it was able to process 200,000 tonnes of oil. At the time, it was supplying 37.6% of the country.

During the period 1960-1990 Rijeka is a city that aspires to the greatest achievements and equips a heavy industry while dreaming of an Utopian tomorrow. After Edo Jardas, the following mayors followed: Franjo Širola (1959–1964), Nikola Pavletić (1964–1968), and Dragutin Haramija (1968–1969), Neda Andrić (1969–1974), Nikola Pavletić for the second time (1974–1979), Vilim Mulc (1979–1982), Josip Štefan (1982–1984), Zdravko Saršon (1985–1987) and Željko Lužavec (1988–1993). The majority of mayors came from small towns in the immediate surroundings of the city.

Regarding the economic situation, the traffic of the port complex had increased from 420,000 tons in 1946 to more than 20,000,000 tons in 1980. The port was involved in more than 50% of traffic across the country and about 80% in terms of transit. In 1980, Rijeka handled 20% of exports from Croatia and 10% of those of Yugoslavia. In 1980, when the merchant navy was at its peak, Rijeka shipping had a cargo capacity of 500,000 tons. Jugolinija was the largest shipping company of the state while Jadrolinija dealt with 49 ships and passenger transportation service by ferry-boats. Approximately 23,000 people were employed in industry in that year. Over 80% of the total industrial production was produced by the energy sector (electric power industry, oil processing and coal), as well as shipbuilding. This feature coupled with the low number of finished products explains why industry of Rijeka collapsed in the early Nineties. In 1982 there were 92,489 employees from a population of 193,000. The oil refinery treated 8,000,000 tonnes - 28% of the total state turnover. The plant had been based in Urinj since 1966. In the Eighties the construction of a petrochemical complex in Omišalj began, which later made one of the biggest losses for the state. The 3 May shipyard handled about one third of the shipbuilding industry. The peak in production was achieved between 1971 and 1975, when 32 ships were built, totalling more than 1,200,000 gross tons. These vessels were mainly for export. In the Eighties smaller boats were built and production increased to employ 7,000 shipyard workers and become the largest company in Rijeka. At the same time the shipyard Viktor Lenac in Martinščica developed to become the largest repairs yard in the Mediterranean.

The development of the metalworking industry was linked to the needs of shipbuilding. Thus Vulkan manufactured cranes for the Rikard Benčić ship pumps, Torpedo manufactured diesel engines and tractors, Rade Končar built electric generators while Metalografički Kombinat was directed towards the production of metal packaging for the purposes of refinery. Civil engineering was expanding to the point that cooperatives such as Primorje, Jadran, Kvarner and Konstruktor employed some 10,000 workers overall in 1981. More than 6,000 of them were engaged in commerce with Brodokomerc. This was reflected in the construction of many new residential buildings in the city such as the five buildings in Škurinje, all 26 floors in height.

The GHETALDUS building on Korzo, designed by Zdenko Kolacio (1949), opens the period of modern architecture. Josip Uhlik designed the building of Social Insurance. Igor Emili created designs for Užarška (1959) and Šporerova (1968) streets, the department store Varteks (1975), the Ri-Adria bank (later Jugobanka, 1986) in the old part of the city, and also for the buildings Kraš (1964) and Brodomaterijal II (1970) on the Korzo. Ada Felice-Rošić designed the store Korzo (1972) with a front flanking a successful access to the old part of town while Ninoslav and Vjera Kučan designed the department store RI (1974). A series of business buildings are the work of Vladimir Grubešić: Jadroagent (1977–1984), Delta (1983–1984), Privredna banka Zagreb (1986), Jadrosped, all located in the old part of town, as well as the Croatia Lines (1982–1992). One of the most accomplished achievements was the construction of the Riječka banka, according to a draft Kazimir Oštrogović (1966). The project of the Museum of the Revolution (now the Municipal Museum) was designed by Neven Šegvić (1976), and the office tower at HPT-Centar Kozala was designed by N. Kučan and V. Antolović (1975). The architect Boris Magaš is the author of two major buildings: the Faculty of Law (1980 with Olga Magaš), and the Church of St. Nicholas (1981–1988).

In independent Croatia

See also

- Corpus separatum (Fiume)

- Postage stamps and postal history of Fiume

- List of governors and heads of state of Fiume

- Other names of Rijeka

- Timeline of Rijeka history

- Imperial Estate

- Free Imperial City

- List of states of the Holy Roman Empire

- History of Croatia

- History of Slovenia

- History of Austria

- History of Hungary

References

- Alcoberro, Agustí (May 2008). Sàpiens (Descobreix la teva història) No 67: La nova Barcelona: La ciutat dels exiliats del 1714 (in Catalan). Sàpiens Publicacions, Revue, Barcelone.

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2003). Austria's Wars of Emergence: War, State and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1683-1797. Pearson Education. p. 224. ISBN 9780582290846. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Colin Thomas, The Anatomy of a Colionization Frontier: The Banat of Temesvar, Austrian History Yearbook, 19-20 (1983-1984), pp. 7-8. (in English)

- Viezzoli, Giuseppe. Fiume durante la dominazione francese (1809-1813), Fiume. Rivista di studi fiumani, Anno XIII-XIV, 1935-1936, pp. 23-99.

- Avakumovic, Ivan. "An Episode In The Continental System in the Illyrian Provinces", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 14. No 3 (Summer, 1954), pp. 254-261.

- Antoljak, Stjepan. "Prekosavska Hrvatska i pitanje njene reinkorporacije (1813 - 1822)", in Stjepan Antoljak, Stjepan. 1994. Hrvati u povijesti, Split, Književni krug, 1992.

- Andics Erzsebet. 1973. Metternich und die Frage Ungarns, Akademiai Kiado, Budapest.

- Žic, Igor. A Short History of the City of Rijeka, Adamić, Rijeka, 2007.

- Riccardo GIGANTE, "Stralcio della corrispondenza di L. A. Adamich col tenente maresciallo Laval Nugent", Fiume (XV-XVI) 1937-1938, p. 131.

- Klinger, William. "Giuseppe Ludovico Cimiotti (1810-1892) e le problematiche origini della storiografia fiumana" (PDF). 'Fiume. Rivista di studi adriatici', (24) 2011, pp. 49 - 64. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Depoli Attilio, L’unione di Fiume alla Corona ungarica ed il suo "iter" legislativo, Fiume Anno X, N.3-4 luglio-dicembre 1963, Pag.97.

- Stanislav Krakov, Dolazak srpske vojske na Rijeku i severni Jadran, Beograd: Jadranska Straza, 1928/29; The Arrival of the Serbian Army in Fiume and the Northern Adriatic

- Anonymous, 1919. Reka-Fiume : notes sur l'histoire, la langue et la statistique, Beograd.

- Ledeen, Michael A. 1977. The First Duce. D’Annunzio at Fiume, Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Federzoni, Luigi. Il Trattato di Rapallo, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1921.

- Benedetti, Giulio. La pace di Fiume, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1924.

- KAKO JE POTOPLJEN KIEBITZ?, Slavko Suzić, Susacka Revija 54/55, 2007, see (in Croatian)

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Rijeka. |

- Europeana. Items related to Rijeka, various dates.

- Giovanni Maria Cassini (1791). "Lo Stato Veneto da terra diviso nelle sue provincie, seconda parte che comprede porzioni del Dogado del Trevisano del Friuli e dell' Istria". Rome: Calcografia camerale. (Map of Fiume region).