History of Riga

The history of Riga, the capital of Latvia, begins as early as the 2nd century with a settlement, the Duna urbs, at a natural harbor not far upriver from the mouth of the Daugava River. Later settled by Livs and Kurs, it was already an established trade center in the early Middle Ages along the Dvina-Dnieper trade route to Byzantium. Christianity had come to Latvia as early as the 9th century, but it was the arrival of the Crusades at the end of the 12th century which brought the Germans and forcible conversion to Christianity; the German hegemony instituted over the Baltics lasted until independence—and is still preserved today in Riga's Jugendstil (German Art Nouveau) architecture.

From the 13th century to the birth of nationalism in the 19th and independence in the 20th, Latvia's and Riga's history are intertwined, a chronicle of the rise and fall of surrounding foreign powers over the Latvians and their territory. As a member of the Hanseatic League, Riga's prosperity grew throughout the 13th–15th centuries—with Riga to become a major center of commerce and later, industry, of whatever empire it found itself subject of.

Today, Riga and its environs are home to close to half of Latvia's inhabitants.

UNESCO has declared Riga's historical center a World Heritage site in recognition of its Art Nouveau architecture, widely considered the greatest collection in Europe, and for its 19th-century buildings in wood.[1]

Founding of Riga

The Daugava River (Western Dvina, Dúna in Old Norse[2]) has been a trade route since antiquity, part of the Viking's Dvina-Dnieper navigation route via portage to Byzantium.[3] A sheltered natural harbor 15 km upriver from the mouth of the Daugava—the site of today's Riga—has been recorded as an area of settlement, the Duna Urbs, as early as the 2nd century,[3] when ancient sources already refer to Courland as a kingdom.[3] It was subsequently settled by the Livs, an ancient Finnic tribe[4] who had arrived during the 5th and 6th centuries,[3] about the same time that Riga began to develop as a center of Viking trade during the early Middle Ages.[3]

Archeological digs at the sites of Riga Town Hall (Albert) Square (Latvian: Rātslaukums) and at the corner of Peldu and Ūdensvada streets[5] offer glimpses into Riga's residents of the 12th century. These show that Riga was inhabited mainly by the Kurs, Kursified Livs, and Livs of the Daugava river basin. They occupied themselves mainly with crafts in bone, wood, amber, and iron; fishing, animal husbandry, and trading.[3][6]

The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia (Chronicle) mentions Riga's earliest recorded fortifications upon a promontory, Senais kalns ("ancient hill"), later razed in the 18th century, becoming the site of Riga's Esplanade.[7] It also testifies to Riga having long been a trading center by the 12th century, referring to it as portus antiquus (ancient port), and describes dwellings and warehouses used to store mostly corn, flax, and hides.[3]

The origin of the name of Riga has been speculated to be related to ancient Celts—based on root similarity to words such as Rigomagos and Rigodunon, or that it is a corrupted borrowing from the Liv ringa meaning loop, referring to the ancient natural harbor formed by the tributary loop of the Daugava and being and earlier and common Liv place name for such formations.[4][8] The evidence is conclusive, however, that Riga owes its name to its already-established role in commerce between East and West,[6] as a borrowing of the Latvian rija, for warehouse, the "y" sound of the "j" later transcribed and hardened in German to a "g"—most notably, Riga is named Rie (no "g") in English geographer Richard Hakluyt's 1589 The Principal Navigations,[9] and the origin of Riga from rija is confirmed by the German historian Dionysius Fabricius (1610):[10] "Riga nomen sortita est suum ab aedificiis vel horreis quorum a litus Dunae magna fuit copia, quas livones sua lingua Rias vocare soliti.[3]" (The name Riga is given to itself from the great quantity which were to be found along the banks of the Duna of buildings or granaries which the Livs in their own language are wont to call Rias.)

German traders began visiting Riga and its environs with increasing frequency toward the second half of the 12th century, via Gotland.[11] Bremen merchants shipwrecked at the mouth of the Daugava[12] established a trading outpost near Riga in 1158. The monk Meinhard of Segeberg, a missionary, arrived from Gotland in 1184.[6][11] Christianity had established itself in Latvia more than a century earlier: Catholicism in western Latvia, with a church built in 1045[3] by Danish merchants,[6] but arriving as early as 870 with the Swedes;[13] Orthodox Christianity being brought to central and eastern Latvia by missionaries.[6] Many Latvians had been already baptised prior to Meinhard's arrival.[3] Meinhard's mission, nevertheless, was no less than mass conversion of the pagans to Catholicism. He settled among the Livs of the Daugava valley at Ikšķile (German: Uexküll), about 20 km upstream from Riga.[6] With their assistance and promise to convert,[14] he built a castle and church of stone—a method heretofore unknown by the Livs and of great value to them in building stronger fortifications against their own enemies.[6][14] Hartwig II, Prince-Archbishop of Bremen, was eager to expand Bremen's power and properties northward and consecrated Meinhard as Bishop of Livonia (from the German: Livland) in 1186,[11] with Ikšķile as bishopric. When the Livs failed to renounce their pagan ways,[14] Meinhard grew impatient and plotted to convert them forcibly. The Livs, however, thwarted his attempt to leave for Gotland to gather forces, and Meinhard died in Ikšķile in 1196, having failed his mission.[15]

Hartwig appointed abbot Berthold of Hanover—who may have already traveled to Livonia[14]—as Meinhard's replacement. In 1198 Berthold arrived with a large contingent of crusaders[15] and commenced a campaign of forced Christianization.[3][6] Latvian legend tells that Berthold galloped ahead of his forces in battle, was surrounded and drew back in fright as someone realizing they have stepped on an asp, at which point the Liv warrior Imants (or, Imauts) struck and speared him to death.[15] Ecclesiastical history faults Berthold's unruly horse for his untimely demise.[14]

The Church mobilized to avenge Berthold's death and defeat of his forces. Pope Innocent III issued a bull declaring a crusade against the Livonians, promising forgiveness of sins to all participants.[15] Hartwig consecrated his nephew, Albert, as Bishop of Livonia in 1199. A year later, Albert landed in Riga[3][15] with 23 ships[14] and 500 Westphalian crusaders.[16] In 1201 he transferred the seat of the Livonian bishopric from Ikšķile to Riga, extorting by force agreement to do so from the elders of Riga.[3]

Today, 1201 is still celebrated as the founding of Riga by Albert—integral to the "bringer of culture" (German: Kulturträger) myth created by later German and ecclesiastical historians that Germans discovered Livonia and brought civilization and religion[14] to the virulently anti-Christian[14] pagans.[3]

Ascent of Riga as a center of German commerce

Under Bishop Albert

1201 was equally significant in marking the first arrival of German merchants in Novgorod, traveling via the Dvina and overland.[11]

Albert established ecclesiastical rule and introduced the Visby code of law.[11] To insure his conquest[17] and defend German merchant trade, the monk Theodoric of Estonia established the Order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword (Fratres Militiae Christi Livoniae, "Order") in 1202 under the aegis of Albert (who was away in Germany),[18] open to both nobles and merchants.[11]

Church history relates that the Livonians were converted by 1206,[14] "baptized in a body"[19] after their defeat at Turaida by German forces including the Liv king Kaupo—who had been baptized under Meinhard around 1189,[20] likely by Theodoric.[18] 1207 marked Albert's start on fortification of the town[11][21] (the city gates, Rātsvārti, are first mentioned in 1210[22]) and Emperor Philip's investing Albert with Livonia as a fief[19] and principality of the Holy Roman Empire[3] with Riga as capital[3] and Albert as prince.[23][24] The surrounding areas of Livonia also came under levy to the Holy Roman Empire.[25] To promote a permanent military presence, territorial ownership was divided between the Church and the Order, with the Church taking Riga and two thirds of all lands conquered and granting the Order, who had sought half, a third.[24] Until then, it had been customary for crusaders to serve for a year and then return home.[24]

Albert had ensured Riga's commercial future by obtaining papal bulls which decreed that all German merchants had to conduct their Baltic trade through Riga.[24] In 1211, Riga minted its first coinage,[3] and Albert laid the cornerstone for the Riga Dom.[26] Riga was not yet secure as an alliance of tribes failed to take Riga.[24] In 1212, Albert led a campaign to compel Polotsk to grant German merchants free river passage.[11] Polotsk conceded Kukenois (Koknese) and Jersika, already captured in 1209, to Albert, recognizing his authority over the Livs and ending their tribute to Polotsk.[27]

Opening the Dvina expanded German trade to Vitebsk, Smolensk, and Novgorod.[11] Riga's rapid growth prompted its withdrawal from Bremen's jurisdiction to become an autonomous episcopal see in 1213.[24]

The oldest parts of Riga were devastated by fire in 1215.[22]

In 1220 Albert established a hospital under the Order for the poor sick ("ad usus pauperum infirmantium hospitale in nova civitate Rige construximusus").[28] In 1225 it became a Holy Ghost Hospital of Germany—a lepers' hospital, although no cases of leprosy were ever recorded there.[28] (In 1330 it became the site of the new Riga Castle.[29])

Albert's knitting of ecclesiastical and secular interests under his person began to fray. Riga's merchant citizenry chafed and sought greater autonomy; in 1221 they acquired the right to independently self-administer Riga[17] and adopted a city constitution.[13]

That same year Albert was compelled to recognize Danish rule over lands they had conquered in Estonia and Livonia.[30] This setback dated to the Archbishop of Bremen's closure of Lübeck—then under Danish suzerainty—to Baltic commerce in 1218. Fresh crusaders could no longer reach Riga, which continued to be under threat from the Livs.[31] Albert was compelled to seek assistance from King Valdemar of Denmark, who had his own designs on the eastern Baltic, having occupied Oesel (the island of Saaremaa)[31] in 1203.[32] The Danes landed in Livonia, built a fortress at Reval (Tallinn), and conquered both Estonian and Livonian territory, clashing with the Germans—who even attempted to assassinate Valdemar.[31] Albert was able to reach an accommodation a year later, however, and in 1222 Valdemar returned all Livonian lands and possessions to Albert's control.[33]

Albert's difficulties with Riga's citizenry continued. With papal intervention, a settlement was reached in 1225 whereby they ceased to pay tax to the Bishop of Riga[22] and acquired the right to elect their magistrates and town councilors.[22]

Albert tended to Riga's ecclesiastical life, consecrating the Dom Cathedral,[3] building St. Jacob's Church[3] for the Livonians' use, outside the city wall,[22] and founding a parochial school at the Church of St. George,[6] all in 1226. He also vindicated his earlier losses, conquering Oesel in 1227 (the concluding event of the Chronicle),[34] and saw the solidification of his early gains as the city of Riga concluded a treaty with the Principality of Smolensk giving Polotsk to Riga.[35] Albert died in January 1229.[36] While he failed his aspiration to be anointed archbishop[19] the German hegemony he established over the Baltics would last for seven centuries.[24]

Member of the Hanseatic League

Riga served as a gateway to trade with the Baltic tribes and with Russia. In 1282 Riga became a member of the Hanseatic League (German Hanse, English Hansa). The Hansa developed out of an association of merchants into a loose trade and political union of North German and Baltic cities and towns. Due to its economic protectionist policies which favored its German members, the League was very successful, but its exclusionist policies produced competitors. Back in 1298 citizens of Riga and Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytenis concluded a treaty, whereby pagan Lithuanian garrison would defend them from the depredations of Teutonic Order.[37] The military contract remained in force until 1313.[37]

Hansa's last Diet convened in 1669, although its powers were already weakened by the end of the 14th century, when political alliances between Lithuania and Poland and between Sweden, Denmark and Norway limited its influence. Nevertheless, the Hansa was instrumental in giving Riga economic and political stability, thus providing the city with a strong foundation which endured the political conflagrations that were to come, down to modern times. As the influence of the Hansa waned, Riga became the object of foreign military, political, religious and economic aspirations. Riga accepted the Reformation in 1522, ending the power of the archbishops. In 1524, a venerated statue of the Virgin Mary in the Cathedral was denounced as a witch, and given a trial by water in the Daugava or Dvina River. The statue floated, so it was denounced as a witch and burnt at Kubsberg.[38]

Under the supremacy of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden

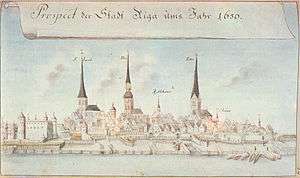

With the demise of the Livonian Order during the Livonian War, Riga for twenty years had the status of a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire before it came under the influence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Treaty of Drohiczyn, which ended the war for Riga in 1581. In 1621, during the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625), Riga and the outlying fortress of Daugavgriva came under the rule of Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, who intervened in the Thirty Years' War not only for political and economic gain but also in favour of German Lutheran Protestantism. During the Russo-Swedish War (1656–1658), Riga withstood a siege by Russian forces.

Riga remained the largest city of the Swedish Empire[39] during a period in which the city retained a great deal of self-government autonomy. In 1710, in the course of Great Northern War, Russia under Tsar Peter the Great besieged Riga. Along with the other Livonian towns and gentry, Riga capitulated to Russia, largely retaining their privileges. Riga was made the capital of the Governorate of Riga (later: Livonia). Sweden's northern dominance had ended, and Russia's emergence as the strongest Northern power was formalised through the Treaty of Nystad in 1721.

Industrial harbor city of the Russian Empire

By the end of the 19th. century Riga had become one of the most industrially advanced and economically prosperous cities in the entire Empire, and of the 800,000 industrial workers in the Baltic provinces, over half worked there. By 1900, Riga was the third largest city in Russia after Moscow and Saint Petersburg in terms of numbers of industrial workers.

During these many centuries of war and changes of power in the Baltic, the Baltic Germans in Riga, successors to Albert's merchants and crusaders, clung to their dominant position despite demographic changes. Riga even employed German as its official language of administration until the imposition of Russian language in 1891 as the official language in the Baltic provinces. All birth, marriage and death records were kept in German up to that year. Latvians began to supplant Germans as the largest ethnic group in the city in the mid-19th century, however, and by 1897 the population was 45% Latvian (up from 23.6% in 1867), 23.8% German (down from 42.9% in 1867 and 39.7% in 1881), 16.1% Russian, 6% Jewish, 4.8% Polish, 2.3% Lithuanian, and 1.3% Estonian. By 1913 Riga was just 13.5% German. The rise of a Latvian bourgeoisie made Riga a center of the Latvian National Awakening with the founding of the Riga Latvian Association in 1868 and the organization of the first national song festival in 1873. The nationalist movement of the Young Latvians was followed by the socialist New Current during the city's rapid industrialization, culminating in the 1905 Russian Revolution led by the Latvian Social Democratic Workers' Party.

Capital of independent Latvia

The 20th century brought World War I and the impact of the Russian Revolution to Riga. The German army marched into Riga in 1917. In 1918 the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed giving the Baltic countries to Germany. Because of the Armistice with Germany (Compiègne) of 11 November 1918, Germany had to renounce that treaty, as did Russia, leaving Latvia and the other Baltic States in a position to claim independence.

After more than 700 years of German, Swedish and Russian rule, Latvia, with Riga as its capital city, declared its independence on 18 November 1918. For more details, see History of Latvia.

Between World War I and World War II (1918–1940), Riga and Latvia shifted their focus from Russia to the countries of Western Europe. A democratic, parliamentary system of government with a President was instituted. Latvian was recognized as the official language of Latvia. Latvia was admitted to the League of Nations. The United Kingdom and Germany replaced Russia as Latvia's major trade partners. As a sign of the times, Latvia's first Prime Minister, Kārlis Ulmanis, had studied agriculture and worked as a lecturer at the University of Nebraska in the United States of America.

Riga was described at this time as a vibrant, grand and imposing city and earned the title of "Paris of the North" from its visitors.

Soviet and Nazi period

There then followed World War II, with the Soviet occupation and annexation of Latvia in 1940; thousands of Latvians were arrested, tortured, executed and deported to labor camps in Siberia, where the survival rate equaled that of Nazi concentration camps, following German occupation in 1941–1944. The Baltic Germans were forcibly repatriated to Germany at Hitler's behest, after 700 years in Riga. The city's Jewish community was forced into a ghetto in the Maskavas neighbourhood, and concentration camps were constructed in Kaiserwald and at nearby Salaspils.

In 1945 Latvia was once again subjected to Soviet domination. Many Latvians were deported to Siberia and other regions of the Soviet Union, usually being accused of having collaborated with the Nazis or of supporting the post-war anti-Soviet Resistance. Forced industrialization and planned large-scale immigration of large numbers of non-Latvians from other Soviet republics into Riga, particularly Russians, changed the demographic composition of Riga. High-density apartment developments, such as Purvciems, Zolitūde, and Ziepniekkalns ringed the city's edge, linked to the center by electric railways. By 1975 less than 40% of Riga's inhabitants were ethnically Latvian, a percentage which has risen since Latvian independence.

In 1986 the modern landmark of Riga, the Riga Radio and TV Tower, whose design is reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower, was completed.

Restoration of independence

The policy of economic reform introduced as Perestroika by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev led to a situation in the late 1980s in which many Soviet republics, including Latvia, were able to regain their liberty and freedom (see Latvia). Latvia declared its full de facto independence on 21 August 1991 and that independence was recognized by Russia on 6 September 1991.

In Riga, Soviet street names and monuments were removed. Lenin Prospect once again became Brīvības (Freedom) Boulevard, and the Oškalns train station, named after a prominent Latvian communist became Zemitani. The Lenin statue that stood alongside the Freedom monument was removed amid nationalist celebrations. The highway connecting Riga to Jūrmala was renamed after Kārlis Ulmanis, Latvia's last pre-Soviet president. During this period of political change, some local Russians and Ukrainians lost their citizenship, and fled to Russia and the West. Nearly all of the Jewish populace emigrated out of the country. The flight of post-war settlers restored Riga's ethnic Latvian majority. Neverthlesess, certain neighborhoods remain majority Russian. Joining European Union, free travel and restoration of civic society is slowly but surely bringing Riga back to its cosmopolitan roots.

Latvia formally joined the United Nations as an independent country on 17 September 1991. All Russian military forces were removed from 1992 to 1994.

- In 2001, Riga celebrated its 800th anniversary as a city.

- On 29 March 2004 Latvia joined NATO.

- On 1 May 2004 Latvia joined the European Union.

- On 1 July 2016 Latvia joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

In 2004, the arrival of low-cost airlines resulted in cheaper flights from other European cities such as London and Berlin and consequently a substantial increase in numbers of tourists.[40] However concerns have been expressed about the misbehaviour of some groups of tourists after two British tourists were caught urinating in Freedom Monument Square[41] prompting the British embassy to issue advice to tourists to behave in a responsible way when drinking.[42] The number of tourists has continued to increase and 2006 saw an 18% rise in the number of people staying in Latvian hotels relative to 2005, the largest increase in the E.U. and well above the European average of 2.4%.[43]

See also

- History of Latvia

- Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation

- Siege of Riga, multiple sieges of Riga

- Timeline of Riga

References

- Historic Centre of Riga, UNESCO site, retrieved 25 July 2009

- Rune Edberg: Vägen till Palteskiuborg, English Summary, retrieved 24 July 2009

- Bilmanis, A. Latvia as an Independent State. Latvian Legation. 1947.

- "Teritorija un administratīvās robežas vēsturiskā skatījumā" (in Latvian). Cities Environmental Reports on the Internet. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Berga Tatjana, Celmiņš Andris. Rīgā Peldu ielā atrastais 13. gadsimta monētu depozīts, LATVIJAS VĒSTURES INSTITŪTA ŽURNĀLS (Journal of the Latvian Historical Institute), 2005, No. 3

- Vauchez et al. Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Routledge, 2001

- Esplanāde, entry in the Latvian Encyclopedia dictionary, retrieved 7 July 2008

- Endzelīns, Did Celts Inhabit the Baltics (1911 Dzimtene's Vēstnesis (Homeland Messenger) No. 227) Archived 9 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 24 July 2009

- Pronouncing the "i" and "e" separately, REE-eh, is the best approximation to the Latvian rija, as "Ria" would result in an "i" not "ee" sound.

- Fabrius, D. Livonicae Historiae Compendiosa Series, 1610

- Dollinger, P. The Emergence of International Business 1200–1800, 1964; translated Macmillan and Co edition, 1970

- Lansdell, H. Baltic Russia", Harper's New Monthly Magazine, July 1890.

- Wright, C.T.H. The Edinburgh Review, THE LETTS, 1917

- Laffort, R. (censor), Catholic Encyclopedia, Robert Appleton Co., 1907

- Germanis, U. The Latvian Saga. 10th ed. 1998. Memento, Stockholm.

- Tolstoy-Miloslavsky, D. The Tolstoys: Genealogy and Origin. A2Z, 1991

- Reiner et al. Riga. Axel Menges, Stuttgart. 1999.

- Zeiferts, T. Ihsa Latwijas Whesture Skolai un wispahribai (A Brief History of Latvia for Scholastic and general use), Cooperative Society "School", Cēsis: 1920. (in Latvian)

- Moeller et al. History of the Christian Church. MacMillan & Co. 1893.

- Uustalu, E. The History of Estonian People. Boreas Pub. Co., 1952.

- Zarina, D. Old Riga: Tourist Guide, Spriditis, 1992

- Švābe, A., ed. Latvju Enciklopēdija. Trīs Zvaigznes, Stockholm. 1953–1955 (in Latvian)

- Krause, et al. Theologische Realenzyklopädie. Walter de Gruyter, 1993.

- Palmieri, A. Catholic Origin of Latvia, ed. Cororan, J.A. et al.The American Catholic Quarterly Review Volume XLVI, January–October 1921. Philadelphia.

- Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2005.

- Doma vēsture (history), Retrieved 29 July 2009

- Kooper, E. The Medieval Chronicle V. Radopi, 2008.

- R. Virchow. Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin. Georg Reimer, Berlin. 1861.

- Turnbull, S.; ill. Dennis, P. Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (2): The Stone Castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Osprey Publishing. 2004.

- Murray, A. Crusade and Conversion on the Baltic Frontier, 1150–1500. Ashgate, London. 2001.

- The Ecclesiastical Review, Vol. LVI. American Ecclesiastical Review. Dolphin Press. 1917.

- Valdemar II, Encyclopædia Britannica. New York, 1911.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt, I. The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, 1147–1254. Brill. 2006.

- Fletcher, R.A. The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity, 371–1386 AD. Harper Collins. 1991.

- Michell, Thomas. Handbook for Travelers in Russia, Poland, and Finland. London, John Murray, 1888.

- Fonnesberg-Schmidt, I. The Popes and the Baltic Crusades, 1147–1254. Brill, 2007

- McKitterick, Rosamond (1995). The new Cambridge medieval history.Vol-6. Cambridge University Press. p. 706. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2003). The Reformation: A History. Penguin. ISBN 0-670-03296-4.

- The Dynamics of Economic Culture in the North Sea and Baltic Region. Uitgeverij Verloren, 2007. ISBN 9789065508829. P. 242.

- Charles, Jonathan (30 June 2005). "Latvia prepares for a tourist invasion". BBC News. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- "UK tourist urinates in Freedom Monument square". The Baltic Times. 21 May 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- "British embassy warns tourists in Latvia: think before you drink". Monsters and Critics. 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 17 August 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- Baltic Outlook, August 2007, p56