History of Florence

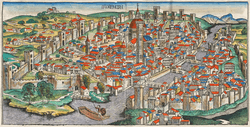

Florence (Italian: Firenze) weathered the decline of the Western Roman Empire to emerge as a financial hub of Europe, home to several banks including that of the politically powerful Medici family. The city's wealth supported the development of art during the Italian Renaissance, and tourism attracted by its rich history continues today.

Prehistoric origins

For much of the Quaternary Age, the Florence-Prato-Pistoia plain was occupied by a great lake bounded by Monte Albano in the west, Monte Giovi in the north and the foothills of Chianti in the south. Even after most of the water had receded, the plain, 50 metres (160 ft) above sea level, was strewn with ponds and marshes that remained until the 18th century, when the land was reclaimed. Most of the marshland was in the region of Campi Bisenzio, Signa and Bagno a Ripoli.

It is thought that there was already a settlement at the confluence of the Mugnone River with the River Arno between the 10th and 8th centuries BC. Between the 7th and 6th centuries BC, Etruscans discovered and used the ford of the Arno near this confluence, closer to the hills to the north and south. A bridge or a ferry was probably constructed here, about ten metres away from the current Ponte Vecchio, but closer to the ford itself. The Etruscans, however, preferred not to build cities on the plain for reasons of defence and instead settled about six kilometres away on a hill. This settlement was a precursor of the fortified centre of Vipsul (today's Fiesole), which was later connected by road to all the major Etruscan centres of Emilia to the north and Lazio to the south.

Classical Florence

Some historians still assert the existence of a Pre-Roman settlement in Florence, arguing the possibility of an urban center destroyed by Sulla.

Written history of Florence traditionally begins in 59 BC, when the Romans founded the village for army veterans, and reportedly dedicated it to the god Mars. According to some stories, the city was founded for precise political and strategic reasons; in 62 BC, Fiesole (a region in Florence) was a cove for Catilines, and Caesar wanted an outpost nearby to monitor the roads and communications.

The Romans built ports at Arno and Mugnone to create advantageous transport positions; old Florence was on the Via Cassia, forming a wedge controlling the end of the Apennine valley of Arno and the beginning of the plane that led to the sea in the direction of Pisa. In 123 AD, a bridge was constructed over the Arno. Buildings began to accumulate around the Roman military camp, including an aqueduct (from Monte Morello), a forum (in today's Piazza della Repubblica), spas, the Roman Theatre of Florence, and the Roman Amphitheatre of Florence, while the surrounding land was organized by centuriation. A nearby river port allowed trade up to Pisa. The outlines of the Roman city are still recognizable in the city's plan, notably the city walls.

In 285 AD, Diocletian established a commander seat in Florence who was responsible for all of Tuscia. Eastern merchants (some from the quarter of Oltrarno) brought the cult of Isis, and later Christianity.

Because Florence rapidly developed over the next several centuries and into the middle ages, few monuments of the Roman period remain in Florence today. Some of the remaining structures include the thermal complex discovered in the Piazza della Signoria, the amphitheater (or at least its road structure), and artifacts remaining at the Florentine National Archaeological Museum and the Museo di Firenze com'era (English: The Museum of Florence as it Was).

Early Middle Ages

The seat of a bishopric from around the beginning of the 4th century CE, the city was ruled alternatively by Byzantine and Ostrogothic potentates as the two powers fought each other for control of the city. The city would be taken by siege only to be lost again later by one of the two powers.

Peace returned under Lombard rule in the 6th century. Conquered by Charlemagne in 774, Florence became part of the March of Tuscany, whose capital was Lucca. The population began to grow again and commerce prospered. In 854, Florence and Fiesole were united in one county.

Middle Ages

Margrave Hugh "the Great" of Tuscany chose Florence as his residence instead of Lucca in about 1000 CE. This initiated a Golden Age of Florentine Art. In 1013, construction was begun on the Basilica di San Miniato al Monte. The exterior of the baptistry was reworked in Romanesque style between 1059 and 1128.

Florence experienced a long period of civic revival beginning in the 10th century and was governed from 1115 by an autonomous medieval commune. But the period of revival was interrupted when the city was plunged into internal strife by the 13th-century struggle between the Ghibellines, supporters of the German emperor, and the pro-Papal Guelphs after the murder of nobleman Buondelmonte del Buondelmonti for reneging on his agreement to marry one of the daughters of the Amidei family.[1] In 1257, the city was ruled by a podestà, the Guelph Luca Grimaldi. The Guelphs had triumphed and soon split in turn into feuding "White" and "Black" factions led respectively by Vieri de' Cerchi and Corso Donati. These struggles eventually led to the exile of the White Guelphs, one of whom was the poet Dante Alighieri. This factional strife was later recorded by Dino Compagni, a White Guelph, in his Chronicles of Florence.

Political conflict did not, however, prevent the city's rise to become one of the most powerful and prosperous in Europe, assisted by its own strong gold currency. The "fiorino d'oro" of the Republic of Florence, or florin, was introduced in 1252, the first European gold coin struck in sufficient quantities to play a significant commercial role since the 7th century. Many Florentine banks had branches across Europe, with able bankers and merchants such as the famous chronicler Giovanni Villani of the Peruzzi Company engaging in commercial transactions as far away as Bruges. The florin quickly became the dominant trade coin of Western Europe, replacing silver bars in multiples of the mark. This period also saw the eclipse of Florence's formerly powerful rival Pisa, which was defeated by Genoa in 1284 and subjugated by Florence in 1406 [2]. Power shifted from the aristocracy to the mercantile elite and members of organized guilds after an anti-aristocratic movement, led by Giano della Bella, enacted the Ordinances of Justice in 1293.

While visiting the ruins of Rome during the jubilee celebration in 1300, the banker and chronicler Giovanni Villani (c. 1276–1348) noted the well-known history of the city, its monuments and achievements, and was then inspired to write a universal history of his own city of Florence. Hence he began to record the history of Florence in a year-by-year format in his Nuova Cronica, which was continued by his brother and nephew after he succumbed to the Black Death in 1348. Villani is praised by historians for preserving valuable information on statistics, biographies, and even events taking place throughout Europe, but his work has also drawn criticism by historians for its many inaccuracies, use of the supernatural and divine providence to explain the outcome of events and glorification of Florence and the papacy.

Renaissance

In 1338, there were about 17,000 beggars in the city. 4,000 were on public relief. There were six primary schools with 10,000 pupils, including girls. Four high schools taught 600 students, including a few girls. They studied literature and philosophy.[3].

Of a population estimated at 80,000 before the Black Death of 1349, about 25,000 are estimated to have been engaged in the city's wool industry. In 1345, Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool carders (ciompi), who in 1378 rose up in a brief revolt against oligarchic rule known as the Revolt of the Ciompi. After their suppression, the city came under the sway of the Albizzi family, bitter rivals of the Medici family, between 1382 and 1434. Cosimo de' Medici (1389–1464) was the first Medici family member to govern the city from behind the scenes. Although the city was technically a democracy of sorts, his power came from a vast network of patronage and a political alliance to new immigrants to the city, the gente nuova. The fact that the Medici were bankers to the pope also contributed to their prominence. Cosimo was succeeded by his son Piero di Cosimo de' Medici (1416–1469), who was shortly thereafter succeeded by Cosimo's grandson, Lorenzo in 1469. Lorenzo de' Medici was a great patron of the arts who commissioned works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli.

After Lorenzo's death in 1492, his son Piero the Unfortunate took the reins of government, however his rule was short. In 1494, King Charles VIII of France invaded Italy and entered Tuscany on his way to claim the throne of the Kingdom of Naples. After Piero made a submissive treaty with Charles, the Florentines responded by forcing him into exile, and the first period of Medici rule ended with the restoration of a republican government. Anti-Medici sentiment was much influenced by the teachings of the radical Dominican prior Girolamo Savonarola. However, in due time, Savonarola lost support and was hanged in 1498. Medici rule was not restored until 1512. The Florentines drove out the Medici for a second time and re-established the Republic on May 16, 1527.

An individual of highly unusual insight into political conditions of this time was Niccolò Machiavelli, whose prescriptions for Florence's regeneration under strong leadership have often been seen as a legitimization of political expediency and even evil. Machiavelli was tortured and exiled from Florence by the Medici family in 1513, due accusations of conspiracy, which was exacerbated because of his ties to the previous republican government of Florence. Commissioned by the Medici, in 1520 Machiavelli wrote the Florentine Histories, a history of the city.[4]

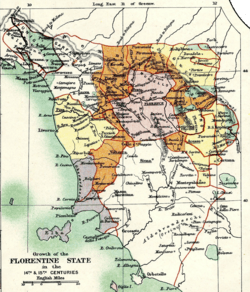

The 10-month Siege of Florence (1529–1530) by the Spanish ended the Republic of Florence and Alessandro de' Medici became the ruler of the city. The siege brought the destruction of its suburbs, the ruin of its export business and the confiscation of its citizens' wealth.[5] Alessandro, who ruled from 1531 to 1537, was the first Medici to use the style Duke of Florence, a title arranged for him in 1532 by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In 1569, Duke Cosimo I was elevated to the rank of Grand Duke of Tuscany by Pope Pius V. The Medici would continue to rule in Tuscany as grand dukes until 1737. After the Battle of Marciano in 1554, the city's historical rival Siena was conquered and the only remaining territory in Tuscany not ruled from Florence was the Republic of Lucca (later a Duchy).

During Renaissance Florence, mobs were both common and influential. Families were pitted against each other in a constant struggle for power. Politically, double-crossings and betrayals were not uncommon, sometimes even within families. Despite political violence, factionalism and corruption, Renaissance Florence did experiment with different forms of citizen government and power sharing arrangements. In order to reconcile the warring factions and families, a complex electoral system was developed as mechanism for sharing power.[6] Incumbent officers and appointees carried out a secret ballot every three or four years. They committed the names of all those elected into a series of bags, one for each sesto, or sixth, of the city. One name was drawn from each bag every two months to form the highest executive authority of the city, the Signoria. The selection scheme was controlled to ensure that no two members of the same family ended up in the same batch of six names.

This lottery arrangement organized the political structure of Florence until 1434, when the Medici family took power. To maintain control, the Medici undermined the selection process by introducing a system of elected committees they could effectively manipulate by fear and favour. Civic lotteries still took place, but actual power rested with the Medicis. In 1465, a movement to reintroduce civic lotteries was halted by an extraordinary commission packed with Medici supporters.[7]

Role in art, literature, music and science

The surge in artistic, literary, and scientific investigation that occurred in Florence in the 14th-16th centuries was facilitated by Florentines' strong economy, based on money, banking, trade, and with the display of wealth and leisure.

In parallel with leisure evolving from a strong economy, the crises of the Catholic church (especially the controversy over the French Avignon Papacy and the Great Schism) along with the catastrophic effects of the Black Death led to a re-evaluation of medieval values, resulting in the development of a humanist culture, stimulated by the works of Petrarch and Boccaccio. This prompted a revisitation and study of the classical antiquity, leading to the Renaissance.[8]

This renaissance thrived locally from about 1434 to 1534. It halted amid social, moral, and political upheaval. By then, the inspiration it had created had set the rest of Western Europe ablaze with new ideas.[3]

Florence benefited materially and culturally from this sea-change in social consciousness. In the arts, the creations of Florentine artists, architects, and musicians were influential in many parts of Europe. The culmination of certain speculations into the nature of ancient Greek drama by humanist scholars led to the birth of opera in the 1590s.

Modern and contemporary age

The extinction of the Medici line and the accession in 1737 of Francis Stephen, duke of Lorraine, the husband of Maria Theresa of Austria, led to Tuscany's inclusion in the territories of the Austrian crown. Austrian rule was to end in defeat at the hands of France and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in 1859, and Tuscany became a province of the united Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

Florence replaced Turin as Italy's capital in 1865 and, in an effort to modernise the city, the old market in the Piazza del Mercato Vecchio and many medieval houses were pulled down and replaced by a more formal street plan with newer houses. The Piazza (first renamed Piazza Vittorio Emmanuele II, then Piazza della Repubblica, the present name) was significantly widened and a large triumphal arch was constructed at the west end. This development was unpopular and was prevented from continuing by the efforts of several British and American people living in the city. Poet Antonio Pucci had written in the 14th century, "There was never so noble a garden as when in Mercato Vecchio the eyes and tastes of the Florentines did feast." The area had, however, decayed from its original medieval splendor. A museum recording the destruction stands nearby today. The country's second capital city was superseded by Rome six years later after the withdrawal of the French troops made its addition to the kingdom possible. A very important role is played in these years by the famous Florentine café Giubbe Rosse from its foundation until the present day.

20th century

In the 19th century, the population of Florence doubled to over 230,000, and in the 20th century reached over 450,000 at one point with the growth of tourism, trade, financial services and the industry. A foreign community came to represent one-quarter of the population in the second half of the 19th century and of this period and writers such as James Irving and the pre-Raphaelite artists captured a romantic vision of the city in their works. Numerous villas of mainly English barons with their eclectic collections of art were bequeathed to the city in this era. Today they are occupied by museums such as the Horne Museum, the Stibbert Museum, Villa La Pietra, etc.

During World War II, the city experienced a year-long German occupation (1943–1944). On September 25, 1943, Allied bombers targeted central Florence, destroying many buildings and killing 215 civilians.[9]

In late July 1944, the British 8th Army closed in as they liberated Tuscany. New Zealand troops stormed the Pian dei Cerri hills overlooking the city. After several days of fighting, German forces retreated and gave way.

During the German retreat, Florence was declared an undefended "open city", prohibiting further shelling and bombing in accordance with the Hague Convention. On 4 August, the retreating Germans decided to detonate charges along the bridges of the Arno linking the district of Oltrarno to the rest of the city, thus making it difficult for the New Zealand, South African and British troops to cross just before liberation. The German officer in charge of the demolitions, Gerhard Wolf, ordered that the Ponte Vecchio was to be spared. Before the war, Wolf had been a student in the city, and his decision has been honored with a memorial plaque on the bridge. Instead, an equally historic area of streets directly to the south of the bridge, including part of the Corridoio Vasariano, was destroyed using mines.[10] Since then, the bridges have been restored exactly to their original forms using as many of the remaining materials as possible, but the buildings surrounding the Ponte Vecchio have been rebuilt in a style combining the old with modern design. The last days of battle for Florence were very intense cause the Italian Fascists resistance skirmish known as Franchi Tiratori[11]. The Allied soldiers who died driving the Germans from Tuscany are buried in cemeteries outside the city, British and Commonwealth soldiers a few kilometers east of the center on the north bank of the Arno ), whilst Americans are about 9 kilometers (5.6 mi) south of the city .

On November 4, 1966, the Arno flooded parts of the city centre, killing at least 40 and damaging millions of art treasures and rare books. There was no warning from the authorities who knew the flood was coming except a phone call to the jewellers on the Ponte Vecchio. Volunteers from around the world came to help rescue the books and art, and the effort inspired multiple new methods of art conservation. Forty years later, there were still works awaiting restoration.[12]

On May 28, 1993, a powerful car bomb exploded in the via de Georgofili, behind the Uffizi, killing five people, injuring numerous others and seriously damaging the Torre dei Pulci, the museum and parts of its collection. The blast has been attributed to the Mafia.[13]

21st century

In 2002, Florence was the seat of the first European Social Forum. There are also several new building and cultural projects, such as that of the Parco della Musica e della Cultura, which will be a vast musical and cultural complex that is currently being built in the Parco delle Cascine (Cascine park). It will host a lyrical theatre containing 2000 places, a concert hall for 1000 spectators, a hall with 3000 seats and an open-air amphitheatre with 3000 spaces. It will host numerous ballets, concerts, lyrical operas and numerous musical festivals. The theatre was inaugurated on April 28, 2011, in honour of the 150th of the Italian unification.[14]

See also

References

- "13th C". washington.edu.

- "First impressive impressions of florence in Italy". 6 February 2006. Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Durant, Will (1953). The Story of Civilization: The Renaissance. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1567310238.

- Machiavelli: A Very Short Introduction By Quentin Skinner

- Sir Francis Adams Hyett (1903). Florence: her history and art to the fall of the republic. Methuen. pp. 505–21.

- Oliver Dowlen, Sorted: Civic Lotteries and the Future of Public Participation, (MASS LBP: Toronto, 2008) pp 36

- Dowlen, Sorted

- Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo: Mysteries of Medici Chapel, SLOVO, Moscow, 2006. ISBN 5-85050-825-2

- "25 settembre 1943 bombardamento di Firenze - Zoomedia.it". zoomedia.it.

- Brucker, Gene (1983). Renaissance Florence. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-520-04695-1.

- Toni, De Santoli (2014). "Quando tra i fiorentini giunse l'ora di regolare i conti". La voce di New York.

- Alison McLean (November 2006). "This Month in History". Smithsonian. 37 (8): 34.

- Cowell, Alan (28 May 1993). "Bomb Outside Uffizi in Florence Kills 6 and Damages Many Works". The New York Times.

- Filippo. "UrbanFile - Firenze | Nuovo Auditorium Nel Parco Della Musica E Della Cultura". Urbanfile.it. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

Further reading

See also: Bibliography of the history of Florence (in Italian) and Timeline of Florence#Bibliography

- Niccolò Machiavelli, Florentine Histories.

- Brucker, Gene A. Florence: The Golden Age 1138-1737 (1998)

- Brucker, Gene A. Renaissance Florence (2nd ed. 1983)

- Cochrane, Eric. Florence in the Forgotten Centuries, 1527-1800: A History of Florence and the Florentines in the Age of the Grand Dukes (1976)

- Crum, Roger J. and John T. Paoletti. Renaissance Florence: A Social History (2008) excerpt and text search

- Goldthwaite, Richard A. The Economy of Renaissance Florence (2009)

- Hibbert, Christopher, Florence: The Biography of a City, Penguin Books, 1994. ISBN 0-14-016644-0

- Holmes, George. The Florentine Enlightenment, 1400-50 (1969)

- Najemy. John M. A History of Florence 1200-1575 (2008) excerpt and text search

Primary sources

- Brucker, Gene A., ed. The Society of Renaissance Florence: A Documentary Study (1971)

Other readings

- Linda Proud's trilogy of novels beginning with A Tabernacle for the Sun gives an excellent introduction to Renaissance Florence, its culture, history and philosophy. http://www.lindaproud.com/

- Eve Borsook, Companion Guide to Florence, is a very in-depth guide to the city and the history of its districts and buildings.

- Oliver Dowlen, Sorted: Civic Lotteries and the Future of Public Participation. (MASS LBP: Toronto, 2008)