Historical romance

Historical romance (also historical novel) is a broad category of fiction in which the plot takes place in a setting located in the past. Walter Scott helped popularize this genre in the early 19th-century, with works such as Rob Roy and Ivanhoe.[1] Literary fiction historical romances continue to be published, and a notable recent example is Wolf Hall (2009), a multi-award-winning novel by English historical novelist Hilary Mantel. It is also a genre of mass-market fiction, which is related to the broader romantic love genre.

Definition

The terms "romance novel" and "historical romance" are ambiguous, because the word "romance", and the associated word "romantic", have a number of different meanings. In particular, on the one hand there is the mass-market genre of "fiction dealing with love", harlequin romance,[2] and on the other hand, "a romance" can also be defined as "a fictitious narrative in prose or verse; the interest of which turns upon marvelous and uncommon incidents".[3] However, many romances, including the historical romances of Walter Scott,[4] are also frequently called novels, and Scott describes romance as a "kindred term".[5] To add to the confusion literary fiction romances, for example Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights, often have a strong love story interest. Other European languages do not distinguish between romance and novel: "a novel is le roman, der Roman, il romanzo."[6]

History

France

In French literature, a prominent inheritor of Walter Scott's style of the historical novel was Balzac.[7] In 1829 Balzac published Les Chouans, a historical work in the manner of Sir Walter Scott.[8] This was subsequently incorporated into La Comédie Humaine. The bulk La Comédie Humaine, however, takes place during the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy, though there are several novels which take place during the French Revolution and others which take place of in the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, including About Catherine de Medici and The Elixir of Long Life.

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) by Victor Hugo is an important French historical romance of the early nineteenth century. The title refers to the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, on which the story is centred, and the true protagonist of the story Esméralda.[9] English translator Frederic Shoberl named the novel "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" in 1833 because at the time, Gothic novels were a popular form of Romance at that time in England.[10] The story is set in Paris, France in the Late Middle Ages, during the reign of Louis XI (1461–1483).

Alexander Dumas's The Three Musketeers (1844) is another famous French historical romance. Set in 1625, it recounts the adventures of a young man named d'Artagnan (based on Charles de Batz-Castelmore d'Artagnan) after he leaves home to travel to Paris, to join the Musketeers of the Guard. Although D'Artagnan is not able to join this elite corps immediately, he befriends the three most formidable musketeers of the age: Athos, Porthos and Aramis and gets involved in affairs of the state and court.

In genre, The Three Musketeers is primarily a historical and adventure novel. However, Dumas also frequently works into the plot various injustices, abuses and absurdities of the old regime, giving the novel an additional political aspect at a time when the debate in France between republicans and monarchists was still fierce. The story was first serialized from March to July 1844, during the July Monarchy, four years before the French Revolution of 1848 violently established the Second Republic. The author's father, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, had been a well-known General in France's Republican army during the French Revolutionary Wars. The story of d'Artagnan is continued in Twenty Years After and The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later.

The twentieth century produced the widely popular Angelique (novel series) by Anne Golon set in the France of Louis XIV.

United Kingdom

Walter Scott is usually seen as the inventor of the modern historical novel and the inspiration for enormous numbers of imitators and genre writers both in the United Kingdom and on the European continent. In the cultural sphere, though Jane Porter was writing successfully in this genre before him.[11] Scott is most famous for his series the Waverley novels. One of the first mass market historical romances Georgette Heyer's The Black Moth appeared in 1921.

Eleanor Hibbert (1906 – 1993) was an English author who published an enormous number of novels, including many historical romances about European royalty under the nom de plume of Jean Plaidy. She combined imagination with facts to bring history alive through novels of fiction and romance. She was a prolific writer who published several books a year in different literary genres, each genre under a different pseudonyms: Victoria Holt for gothic romances, and Philippa Carr for a multi-generational family saga. A literary split personality, she also wrote light romances, crime novels, murder mysteries and thrillers under the names Eleanor Burford, Elbur Ford, Kathleen Kellow, Anna Percival, and Ellalice Tate. Some of the numerous historical romance series Hibbert published, as Jean Plaidy, sre: The Tudor Saga; The Catherine De Medici Trilogy; The Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots Series;The French Revolution Series; The Georgian Saga; The Queen Victoria Series; The Norman Trilogy.

United States

James Fenimore Cooper (1789 – 1851) was a prolific and popular American writer of the early 19th century. His historical romances of frontier and Indian life in the early American days created a unique form of American literature.[12] Before embarking on his career as a writer he served in the U.S. Navy as a Midshipman, which greatly influenced many of his novels and other writings. The novel that launched his career was The Spy, set during the Revolutionary War and published in 1821.[13] He also wrote numerous sea stories and his best-known works are five historical novels known as the Leatherstocking Tales. Though some scholars have hesitated to classify Cooper as a strict Romantic, Victor Hugo pronounced him greater than the great master of modern romance. This verdict was echoed by a multitude of less famous readers, such as Balzac and Rudolf Drescher of Germany, who were satisfied with no title for their favourite less than that of the "American Scott."[14]

The modern mass-market romance genre was born in America 1972 with Avon's publication of Kathleen Woodiwiss's historical romance The Flame and the Flower. Set around 1900. it is the first romance novel "to [follow] the principals into the bedroom."[15][16] Aside from its content, the book was revolutionary in that it was one of the first single-title romance novels to be published as an original paperback, rather than being first published in hardcover, and, like the category romances, was distributed in drug stores and other mass-market merchandising outlets.[17] The novel went on to sell 2.35 million copies.[18] Avon followed its release with the 1974 publication of Woodiwiss's second novel, The Wolf and the Dove and two novels by newcomer Rosemary Rogers. One of Rogers's novels, Dark Fires sold two million copies in its first three months of release, and, by 1975, Publishers Weekly had reported that the "Avon originals" had sold a combined 8 million copies.[17] The following year over 150 historical romance novels, many of them paperback originals, were published, selling over 40 million copies.[18] Unlike Woodiwiss, Rogers's novels featured couples who travelled the world, usually were separated for a time, and had multiple partners within the book.[19] The success of these novels prompted a new style of writing romance, concentrating primarily on historical fiction tracking the monogamous relationship between a helpless heroines and the hero who rescued her, even if he had been the one to place her in danger.[20] The covers of these novels tended to feature scantily clad women being grabbed by the hero, and caused the novels to be referred to as "bodice-rippers."[15] A Wall St. Journal article in 1980 referred to these bodice rippers as "publishing's answer to the Big Mac: They are juicy, cheap, predictable, and devoured in stupifying quantities by legions of loyal fans."[21] The term bodice-ripper is now considered offensive to many in the romance industry.[15]

In this new style of historical romance, heroines were independent and strong-willed and were often paired with heroes who evolved into caring and compassionate men who truly admired the women they loved.[22] This was in contrast to the contemporary romances published during this time, which were often characterized by weak females who fell in love with overbearing alpha males.[23] Although these heroines had active roles in the plot, they were "passive in relationships with the heroes",[24] Across the genre, heroines during this time were usually aged 16–21, with the heroes slightly older, usually around 30. The women were virgins, while the men were not, and both members of the couple were described as beautiful.[25]

In the late 1980s, historical romance dominated the romance genre. The most popular of the historical romances were those that featured warriors, knights, pirates, and cowboys.[26] In the 1990s the genre began to focus more on humor, as Julie Garwood began introducing humorous elements and characters into her historical romances.[26]

Mass market

Mass-market historical romance novels are rarely published in hardcover, with fewer than 15 receiving that status each year. The contemporary market usually sees 4 to 5 times that many hardcovers. Because historical romances are primarily published in mass-market format, their fortunes are tied to a certain extent to the mass-market trends. Booksellers and large merchandisers are selling fewer mass market paperbacks, preferring trade paperbacks or hardcovers, which prevent historical romances from being sold in some price clubs and other mass merchandise outlets.[27] In 2001, this genre reached a 10-year high as 778 were published. By 2004, that number had dropped to 486, which was still 20% of all romance novels published. Kensington Books claims that they are receiving fewer submissions of historical novels, and that their previously published authors are switching to contemporary.[27][28]

Types by period

Ancient world

Egypt

Upper Egypt, Lower Egypt (Nubia). From c. 3050 BC

Greece

Rome

Roman Kingdom, from c. 900 BC. Roman Republic, from c. 500 BC. Roman Empire, from c. 45 BC.

Medieval

These historical romances are set between 450 and 1485.[29]

Women in the medieval period were often considered as no more than property and were forced to live at the mercy of their father, guardian, or the king. In this type of genre fiction the heroine is always from the aristocracy, and she must use her wits and will in order find a husband who will accept her need to be independent, while at the same time protecting her from danger. The hero is almost always a knight who first learns to respect her, and her uncommon ideas, and then falls in love with her. Heroes are always strong and dominant, and the heroine, despite her independent spirit, is usually still in a subordinate position. However, that position is her choice, made "for the sake of and with protection from an adoring lover, whose main purpose in life is to fulfill his beloved's wishes."[30]

Walter Scott's Ivanhoe is a historical novel by, first published in 1820 in three volumes and subtitled A Romance. It is set in 12th century England, has been credited for increasing interest in romance and medievalism; John Henry Newman claimed Scott "had first turned men's minds in the direction of the Middle Ages", while Carlyle and Ruskin made similar assertions of Scott's overwhelming influence over the revival based primarily on the publication of this novel.[31]

The twentieth century British novelist John Cowper Powys, who was influenced by Walter Scott, wrote two major historical romances, Owen Glendower (1941) and Porius: A Romance of the Dark Ages (1951). Owen Glendower set in at the time of Owen Glendower's uprising against King Henry IV, though "Powys has elected to cover only a few incidents in the revolt, principally during the years 1400-1405", with the concluding chapter focussing on November 1416 AD, and the death of Glendower.[32] Porius is set in the Dark Ages during a week of autumn 499 AD, this novel is, in part, a bildungsroman, with the adventures of the eponymous protagonist Porius, heir to the throne of Edeyrnion, in North Wales, at its centre. The novel draws from both Arthurian legend and Welsh history and mythology, with Myrddin (Merlin) as another major character. The invasion of Wales by the Saxons and the rise of the new religion of Christianity are central themes.

Charles Kingsley's Hereward the Wake: Last of the English (1866) tells the story of Hereward, the last Anglo-Saxon holdout against the Normans. It was Kingsley's last historical novel, and was instrumental in elevating Hereward into an English folk-hero.[33] Tim Severin is a more recent novelist who has written several novels about the Saxons: The Book of Dreams (2012); The Emperor's Elephant (2013); The Pope's Assassin (2015).

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote several historical romances including The Black Arrow: A Tale of the Two Roses (1888), and Kidnappped (1886). The Black Arrow is both a historical adventure novel and a romance novel, which is set at the time of the War of the Roses, in the late fifteenth century. Kidnapped is also historical fiction adventure novel. Written as a "boys' novel" and first published in the magazine Young Folks from May to July 1886. The novel has attracted the praise and admiration of writers including Hilary Mantel.[34] A sequel, Catriona, was published in 1893. This novel is set in 18th-century Scotland, and deals with the "Appin Murder", which occurred near Ballachulish in 1752 in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1745.[35][36] Many of the characters are based on real people, including one of the principals, Alan Breck Stewart. The political situation of the time is portrayed from different viewpoints, and the Scottish Highlanders are treated sympathetically.

Viking

These books are set during the early Middle Ages.[29]

Heroes in mass market Viking romances are typical alpha males who are tamed by their heroines. Most heroes are described as "tall, blonde, and strikingly handsome."[37] Using the Viking culture allows novels set in this time period to include travel, as the Vikings were "adventurers, founding and conquering colonies all over the globe."[37] In a 1997 poll of over 200 readers of Viking romances, Johanna Lindsey's Fires of Winter (1980) was considered the best of the subgenre. The subgenre has fallen out of style, and few novels in this vein have been published since the mid-1990s.[37]

Canadian author Joan Clark (1934- ) has written two novels based on the Viking presence in Newfoundland: Eiriksdottir: A Tale of Dreams and Luck (1993). which focuses on Freydis Eiriksdottir, daughter of Erik the Red and sister to Leif ("The Lucky") Eirikson; and The Dream Carvers (1995), which follows the adventures of Thrand, a Norse child abducted by the Beothuk in eleventh-century Newfoundland. The Dream Carvers won the Geoffrey Bilson Award for Historical Fiction for Young People. Joan Clark also won the Vicky Metcalf Award in 1999 in recognition for a body of work that has been "inspirational to Canadian youth."[38]

Tim Severin wrote several Viking novels: Odinn's Child (2005); Sworn Brother (2005); King's Man (2005).

Arthurian fiction

Arthurian fiction is also categorised as fantasy fiction.

Mary Stewart (1916 – 2014), was a British novelist who developed the romantic mystery genre, featuring smart, adventurous heroines who could hold their own in dangerous situations. She also wrote children's books and poetry, but may be best known for her Merlin series, Arthurian novels which straddles the boundary between the historical novel and fantasy.

Renaissance

Tudor England

Set in England between 1485 and 1558.[29]

The Tower of London is a novel by William Harrison Ainsworth serially published in 1840. It is a historical romance that describes the history of Lady Jane Grey from her short-lived time as Queen of England to her execution.

Hilary Mantel (1952 – ) is a prominent contemporary writer of historical romances (or novels). Wolf Hall, published in 2009 to critical acclaim, is about Henry VIII's minister Thomas Cromwell.[39] The book won that year's Man Booker Prize and, upon winning the award, Mantel said, "I can tell you at this moment I am happily flying through the air".[40] Judges voted three to two in favour of Wolf Hall for the prize. Mantel was presented with a trophy and a £50,000 cash prize during an evening ceremony at the London Guildhall.[41][42] The panel of judges, led by the broadcaster James Naughtie, described Wolf Hall as an "extraordinary piece of storytelling".[43] Leading up to the award, the book was backed as the favourite by bookmakers and accounted for 45% of the sales of all the nominated books.[41] It was the first favourite since 2002 to win the award.[44]

The sequel to Wolf Hall, called Bring Up the Bodies, was published in May 2012 to wide acclaim. It won the 2012 Costa Book of the Year and the 2012 Man Booker Prize; Mantel thus became the first British writer and the first woman to win the Man Booker Prize more than once.[45][46] Mantel has published the third novel of the Thomas Cromwell trilogy, called The Mirror and the Light.[47][48]

Elizabethan England

Set in England between 1558 and 1603, during the time of Elizabeth I.[29]

Victorian novelist Charles Kingsley's Westward Ho! (1855) is a British historical novel is set in the Elizabethan era that follows the adventures of Amyas Leigh who sets sail with Francis Drake and other privateers to the Caribbean, where they fight with the Spanish.

Stuart England

Set between 1603 and 1714 in England.[29]

Old St. Paul's, is a novel by William Harrison Ainsworth serially published in 1841. It is a historical romance set in 1665-66 that describes the events of the Great Plague of London and the Great Fire of London (1666). It was the basis for the silent film Old St. Paul's.

Georgian England

Set between 1714 and 1811 in England.[29]

Walter Scott's Rob Roy takes place just before the Jacobite rising of 1715, with much of Scotland in turmoil.

Georgette Heyer's The Black Moth (1921) is set in 1751. The story follows Lord Jack Carstares, an English nobleman who becomes a highwayman after taking the blame during a cheating scandal years before. One day, he rescues Miss Diana Beauleigh when she is almost abducted by the Duke of Andover. Jack and Diana fall in love but his troubled past and current profession threaten their happiness.

Richard Blackmore's Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor (1869) is a romance based on a group of historical characters set in the late 17th century in Devon and Somerset, particularly around the East Lyn Valley area of Exmoor. In 2003, the novel was listed on the BBC's survey The Big Read.[49]

Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped is a historical fiction adventure novel, that was originally published as a "boys' novel" and first published in the magazine Young Folks from May to July 1886. The novel has attracted the praise and admiration of writers as diverse as Henry James, Jorge Luis Borges, Hilary Mantel,[34] and Seamus Heaney. A sequel, Catriona, was published in 1893. The novel is set around 18th-century Scottish events, notably the "Appin Murder", which occurred near Ballachulish in 1752 in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1745.[35][36] Many of the characters were real people, including one of the principals, Alan Breck Stewart. The political situation of the time is portrayed from different viewpoints, and the Scottish Highlanders are treated sympathetically.

Modern period

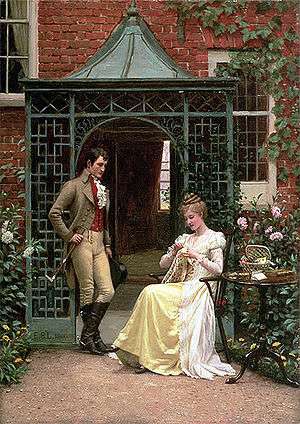

Regency England

Set between 1811 and 1820 in England.[29]

In 1935 Georgette Heyer wrote the first of her signature Regency novels, set around the English Regency period (1811–1820), when the Prince Regent ruled England in place of his ill father, George III. Heyer's Regency novels were inspired by Jane Austen's novels of the late 18th and early 19th century. Because Heyer's writing was set in the midst of events that had occurred over 100 years previously, she included authentic period detail in order for her readers to understand.[50] Where Heyer referred to historical events, it was as background detail to set the period, and did not usually play a key role in the narrative. Heyer's characters often contained more modern-day sensibilities, and more conventional characters in the novels would point out the heroine's eccentricities, such as wanting to marry for love.[51]

Other writers of historical romances set at this time include Christina Dodd, Eloisa James, and Amanda Quick. The Regency historical romance has been made popular in recent years by Mary Balogh, Jo Beverley, Loretta Chase, Lisa Kleypas, Stephanie Laurens, and Julia Quinn. These novels are much more explicit than the traditional Regency works and include many more love scenes.

French Revolution

Baroness Emma Orczy (1865–1947) was a Hungarian-born British novelist, playwright, and artist of noble origin. In 1903, she and her husband wrote a play, The Scarlet Pimpernel, based on one of her short stories about an English aristocrat, Sir Percy Blakeney, Bart., who rescued French aristocrats from the French Revolution. She submitted her novelization of the story under the same title to 12 publishers. While waiting for the decisions of these publishers, Fred Terry and Julia Neilson accepted the play for production in the West End. Initially, it drew small audiences, but the play ran four years in London, broke many stage records, was translated and produced in other countries, and underwent several revivals. This theatrical success generated huge sales for the novel. Orczy went on to write over a dozen sequels featuring Sir Percy Blakeney, his family, and the other members of the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel, of which the first, I Will Repay (1906), was the most popular.

Victorian England

Set between 1832 and 1901 England, beginning with the Reform Act 1832 and including the reign of Queen Victoria.[29] A popular type of historical romance of this period was set a fictional country, such as the Ruritanian novels

Romantic stories about the royalty of a fictional kingdom were common in fiction, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for instance Robert Louis Stevenson's Prince Otto (1885), Anthony Hope's The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), and Beatrice Heron-Maxwell, The Queen Regent (1902).[52] But it was the great popularity of that novel that set the type, with its handsome political decoy restoring the rightful king to the throne, and resulted in a burst of similar popular fiction, such as George Barr McCutcheon's Graustark novels (1901–27) and Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Lost Prince (1915), and there were various other works influenced by The Prisoner of Zenda.[53] Another example is The Mask of Dimitrios (1939) by Eric Ambler (titled A Coffin for Dimitrios in the US), which was made into a 1944 film version.[54]

Russian Revolution

First published in 1957, Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago, set over the course of World War One and the Russian Revolution, won its author the Nobel Prize for Literature which caused some controversy since his book Doctor Zhivago was banned in the Soviet Union during this time.

Types by setting

English North America

Colonial United States

These novels are all set in the United States between 1630 and 1798.[29]

Fenimore Cooper's literary career was launched with The Spy (1821), a tale about counterespionage set during the Revolutionary War.[13] Nathaniel Hawthorne was another writer of historical romances, including his most famous work, The Scarlet Letter: A Romance (1850). Set in 17th-century Puritan Boston, Massachusetts, during the years 1642 to 1649, it tells the story of Hester Prynne, who conceives a daughter through an affair and struggles to create a new life of repentance and dignity. Throughout the book, Hawthorne explores themes of legalism, sin, and guilt.

Civil War

These novels place their characters within the events of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction era. They may be set in the Confederacy or the Union.[29]

William Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom (1936) is an example of a historical romance written by a twentieth century modernist. This takes place before, during, and after the American Civil War, and is a story about three families of the American South.

Western

These novels are set in the frontier of the United States, Canada, or Australia.[29] Unlike Westerns, where women are often marginalized, the Western genre fiction romance focuses on the experiences of the female.[55] Heroes in these novels seek adventure and are forced to conquer the unknown. They are often loners, slightly uncivilized, and "earthy."[56] Their heroines are often forced to travel to the frontier by events outside their control. These women must learn to survive in a man's world, and, by the end of the novel, have conquered their fears with love. In many cases the couple must face a level of personal danger, and, upon surmounting their troubles, are able to forge a strong relationship for the future.[56]

Fenimore Cooper is a noted nineteenth century writer of literary fiction romances that are set on the American frontier. Cooper's best-known works are five Leatherstocking Tales. Among the most famous of these works is The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (1826), often regarded as his masterpiece.[57]

Guy Vanderhaeghe (1951 – ) is a Canadian novelist and short story writer, best known for his Western novels trilogy, The Englishman's Boy, The Last Crossing, and A Good Man set in the 19th-century American and Canadian West. Vanderhaeghe has won three Governor General's Awards for his fiction, one for his short story collection, Man Descending, in 1982, the second for his novel, The Englishman's Boy, in 1996, and the third for his short story collection Daddy Lenin and Other Storiesin 2015.

Native American

These novels could also fall into the Western subgenre, but always feature a Native American protagonist whose "heritage is integral to the story."[29] These romances "[emphasize] instinct, creativity, freedom, and the longing to escape from the strictures of society to return to nature."[58] Members of Native American tribes who appear in the books are usually depicted as "exotic figures" who "[possess] a freedom to be admired and envied."[58] Often the Native protagonist is struggling against racial prejudice and incurs hardships trying to maintain a way of life that is different from the norm. By the end of the novel, however, the problems are surmounted.[59] The heroes of these novels are often fighting to control their darker desires.[58] In many cases, the hero or heroine is captured and then falls in love with a member of the tribe. The tribe is always depicted as civilized, not savages, and misunderstood.[58]

When surveyed about their reasons for reading Native American romances, many readers cited the desire to learn about the beliefs, customs and culture of the Native American tribes. The novels within this subgenre are generally not limited to a specific tribe, location, or time period. Readers appreciate that native tribes "have a whole different way of life, a different way of thinking and a different way of looking at things".[59] In many cases, the tribe's love of nature is highlighted.[59]

Americana

Americana: "Things produced in the U.S. and thought to be typical of the U.S. or its culture".[60] Novels set between 1880 and 1920 in the United States, usually in a small town or in the Midwest.[29]

Nautical

Some historical novels explore life at sea, including C. S. Forester's Hornblower series, Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey–Maturin series, Alexander Kent's The Bolitho novels, Dudley Pope's Lord Ramage's series, all of which all deal with the Napoleonic Wars. American Fenimore Cooper, who served in the American Navy also wrote se stories, including The Red Rover and The Water Witch.

Pirate

There are adventure novels with pirate characters like Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island (1883), Emilio Salgari's Sandokan (1895–1913) and Captain Blood (1922) by Rafael Sabatini. Recent examples of historical novels about pirates are The Adventures of Hector Lynch series (2007–14) by Tim Severin, The White Devil (Белият Дявол) by Hristo Kalchev and The Pirate Devlin novels by Mark Keating.

Pirate novels feature a male or female who is sailing, or thought to be sailing, as a pirate or privateer on the high seas. Pirate heroes are the ultimate "bad boys," who "dominate all for the sake of wealth and freedom."[61] The heroine is usually captured by the hero in an early part of the novel, and then is forced to succumb to his wishes, though eventually she falls in love with her captor. On the rarer occasions where the heroine is the pirate, the book often focuses on her struggle to maintain her freedom of choice while living the life of a man. Regardless of the sex of the pirate, much of the action in the book takes place at sea.[61]

References

Citations

- Christiansen, Rupert (2004) [1988], Romantic Affinities: Portraits From an Age, 1780–1830 (paperback reprint ed.), London: Pimlico, pp. 192–96, ISBN 1-84413421-0.

- "New Oxford American Dictionary.

- .Walter Scott, "Essay on Romance", Prose Works volume vi, p. 129, quoted in "Introduction" to Walter Scott's Quentin Durward, Susan Maning, ed Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Susan Maning, "Introduction" to Walter Scott's Quentin Durward, pp.xxv-xxvii.

- Walter Scott, "Essay on Romance", p. 129.

- Doody (1996), p. 15.

- Lukacs 92-96

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Honoré de Balzac". Books and Writers. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

- hubpages.com/entertainment/the-multi-faceted-esmeralda

- hubpages.com/entertainment/quasimodo

- Thomas McLean, "Nobody's Argument: Jane Porter and the Historical Novel". Journal for Early Modern Culture Studies 7 (2) (2007), pp. 88–103.

- Lounsbury, 1883, pp. 7–8

- Clary, Suzanne (2010). "James Fenimore Copper and Spies in Rye". www.myrye.com.

- Phillips, 1913, p. 160

- Athitakis, Mark (July 25, 2001). "A Romance Glossary". SF Weekly. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Zaitchik, Alexander (July 22, 2003). "The Romance Writers of America convention is just super". New York Press. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Thurston, pp 47–48.

- Darrach, Brad (January 17, 1977). "Rosemary's Babies". Time. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- Marble, Anne (May 15, 2003), "Bodice-Rippers & Super Couples", At the Back Fence, All About Romance Novels (160), archived from the original on April 27, 2007, retrieved April 30, 2007

- White, Pamela (August 15, 2002). "Romancing Society". Boulder Weekly. Archived from the original on September 4, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Thurston, p 67.

- Thurston, p 72.

- Grossman, Lev (February 3, 2003). "Rewriting the Romance" (PDF). Time. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- Crusie, Jennifer (1998). "This Is Not Your Mother's Cinderella: The Romance Novel as Feminist Fairy Tale". In Kaler, Anne; Johnson-Kurek, Rosemary (eds.). Romantic Conventions. Bowling Green Press. pp. 51–61.

- Thurston, p 75.

- Wiggs, Susan (May 25, 2003). "And Now (as usual), Something New". All About Romance Novels. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- Dyer, Lucinda (June 13, 2005). "Romance: In Its Own Time". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- "Romance Writers of America's 2005 Market Research Study on Romance Readers" (PDF). Romance Writers of America. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- "Historical Designations: Genres, Time Periods & Locations". Likes books. All About Romance. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved July 19, 2007.

- Benninger, Gerry (July 1999). "Themes: Medieval Knights". Romantic Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Alice Chandler, "Sir Walter Scott and the Medieval Revival," Nineteenth-Century Fiction 19.4 (March 1965): 315–332.

- John Brebner, The Demon Within: A Study of John Cowper Powys's Novels (London: Macdonald, 1973), pp.161-62.

- Paul Dalton, John C. Appleby, (2009), Outlaws in Medieval and Early Modern England, page 7. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754658937

- Mantel, Hilary Mantel. "The Art of Fiction No. 226 - Hilary Mantel". Paris Review. The Paris Review. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- Auslan Cramb (November 14, 2008). "18th Century murder conviction 'should be quashed'". The Daily Telegraph.

- Stevenson changed the date of the Appin murder from May 1752 to June 1751.

- Ryan, Kate (October 1997). "Vikings". Romantic Times. Archived from the original on September 7, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- "Joan Clark". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- Flood, Alison (8 September 2009). "Man Booker prize shortlist pits veteran Coetzee against bookies' favourite Mantel". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- "Mantel named Booker Prize winner". BBC News. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Brown, Mark (6 October 2009). "Booker prize goes to Hilary Mantel for Wolf Hall". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Mukherjee, Neel (6 October 2009). "The Booker got it right: Mantel's Cromwell is a book for all seasons". The Times. London. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- Hoyle, Ben (6 October 2009). "Man Booker Prize won by Hilary Mantels tale of historical intrigue". The Times. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- Pressley, James and Anderson, Hephzibah (6 October 2009). "Hilary Mantel's 'Wolf Hall' Wins U.K. Man Booker, 50,000 Pounds". Bloomberg. Retrieved 14 May 2012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Hilary Mantel First Woman To Win Booker Prize Twice". NPR.org. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- "Hilary Mantel's Heart of Stone". Slate. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Hilary Mantel reveals plans for Wolf Hall trilogy". BBC News. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Hilary Mantel wins 2012 Costa novel prize". BBC News. 2 January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 1 December 2012

- Regis (2003), pp. 125–26.

- Regis (2003), p. 127.

- "Authors : Heron-Maxwell, Beatrice : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- "Prisoner of Zenda, The (unabridged)". January 27, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Sutherland, John. Bestsellers: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2007), p. 113 ISBN 019157869X

- Regis, Pamela (2003). A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 163. ISBN 0-8122-3303-4.

- Martin, Constance (September 1999). "Themes: Frontier". Romantic Times. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Hale, 1896, p. 657.

- Martin, Constance (November 1999). "Themes: Native Americans". Romantic Times. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- Kitzmiller, Chelley (November 3, 1997). "Write Byte: The Allure of the Native American Romance". All About Romance. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Definition of AMERICANA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Ryan, Kate (January 1998). "Themes: Pirates". Romantic Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

Bibliography

- Regis, Pamela (2003). A Natural History of the Romance Novel. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3303-4.

- Thurston, Carol (1987). The Romance Revolution. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01442-1.

- Scott, Susan Holloway (2017), "Following the Path of Historical Romance to Women's History", National Women's History Museum