Hirsutism

Hirsutism is excessive body hair in men and women on parts of the body where hair is normally absent or minimal. It may refer to a "male" pattern of hair growth that may be a sign of a more serious medical condition,[2] especially if it develops well after puberty.[3] Cultural stigma against hirsutism can cause much psychological distress and social difficulty.[4] Facial hirsutism often leads to the avoidance of social situations and to symptoms of anxiety and depression.[5]

| Hirsutism | |

|---|---|

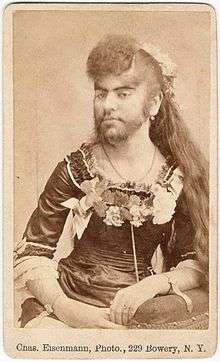

| |

| Barbara van Beck, as depicted in an engraving by G. Scott. | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, endocrinology |

| Treatment | Birth control pills, antiandrogens, insulin sensitizers[1] |

Hirsutism is usually the result of an underlying endocrine imbalance, which may be adrenal, ovarian, or central.[6] It can be caused by increased levels of androgen hormones. The amount and location of the hair is measured by a Ferriman-Gallwey score. It is different from hypertrichosis, which is excessive hair growth anywhere on the body.[2]

Treatments may include birth control pills that contain estrogen and progestin, antiandrogens, or insulin sensitizers.[1]

Hirsutism affects between 5–15% of all women across all ethnic backgrounds.[7] Depending on the definition and the underlying data, estimates indicate that approximately 40% of women have some degree of facial hair.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Hirsutism affects members of either sex, since rising androgen levels can cause excessive body hair, particularly in locations where women normally do not develop terminal hair during puberty (chest, abdomen, back, and face).

Causes

Hirsutism can be caused by either an increased level of androgens, the male hormones, or an oversensitivity of hair follicles to androgens. Male hormones such as testosterone stimulate hair growth, increase size and intensify the growth and pigmentation of hair. Other symptoms associated with a high level of male hormones include acne, deepening of the voice, and increased muscle mass. The condition is called hyperandrogenism.

Growing evidence connects high circulating levels of insulin in women to the development of hirsutism. This theory is speculated to be consistent with the observation that obese (and thus presumably insulin resistant hyperinsulinemic) women are at high risk of becoming hirsute. Further, treatments that lower insulin levels will lead to a reduction in hirsutism.

It is speculated that insulin, at high enough concentration, stimulates the ovarian theca cells to produce androgens. There may also be an effect of high levels of insulin to activate insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor in those same cells. Again, the result is increased androgen production.

Signs that are suggestive of an androgen-secreting tumor in a patient with hirsutism is rapid onset, virilization and palpable abdominal mass.

The following are conditions and situations that have been associated with hyperandrogenism and hence hirsutism in women:

- Hyperinsulinemia (insulin excess) or hypoinsulinemia (insulin deficiency or resistance as in diabetes).

- Ovarian cysts such as in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the most common cause in women.[9]

- Ovarian tumors such as granulosa tumors, thecomas, Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors (androblastomas), and gynandroblastomas, as well as ovarian cancer.

- Hyperthecosis.

- Pregnancy.

- Adrenal gland tumors, adrenocortical adenomas, and adrenocortical carcinoma, as well as adrenal hyperplasia due to pituitary adenomas (as in Cushing's disease).[10]

- hCG-secreting tumors

- Inborn errors of steroid metabolism such as in congenital adrenal hyperplasia, most commonly caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency.[10]

- Acromegaly and gigantism (growth hormone and IGF-1 excess), usually due to pituitary tumors.[10]

- Use of certain medications such as androgens/anabolic steroids, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

Causes of hirsutism not related to hyperandrogenism include:

Diagnosis

A complete physical evaluation should be done prior to initiating more extensive studies, the examiner should differentiate between widespread body hair increase and male pattern virilization.[13] One method of evaluating hirsutism is the Ferriman-Gallwey Score which gives a score based on the amount and location of hair growth on a woman.[14] After the physical examination, laboratory studies and imaging studies can be done to rule out further causes.

Diagnosis of patients with even mild hirsutism should include assessment of ovulation and ovarian ultrasound, due to the high prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), as well as 17α-hydroxyprogesterone (because of the possibility of finding nonclassic 21-hydroxylase deficiency[15]). Many women present with an elevated serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) level. Levels greater than 700 μg/dL are indicative of adrenal gland dysfunction, particularly congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency.[13] However, PCOS and idiopathic hirsutism make up 90% of cases.[13]

Other blood value that may be evaluated in the workup of hirsutism include:

- androgens; androstenedione, testosterone

- thyroid function panel; thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4)

- prolactin

If no underlying cause can be identified, the condition is considered idiopathic.

Treatment

Many women with unwanted hair seek methods of hair removal. However, the causes of the hair growth should be evaluated by a physician, who can conduct blood tests, pinpoint the specific origin of the abnormal hair growth, and advise on the treatment.

Medications

Medications consist mostly of antiandrogens, drugs that block the effects of androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the body, and include:[10]

- Spironolactone: An antimineralocorticoid with additional antiandrogenic activity at high dosages[16][17]

- Cyproterone acetate: A dual antiandrogen and progestogen.[17] In addition to single form, it is also available in some formulations of combined oral contraceptives at a low dosage (see below).[17] It has a risk of liver damage.

- Flutamide: A pure antiandrogen.[17] It has been found to possess equivalent or greater effectiveness than spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, and finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism.[18][17] However, it has a high risk of liver damage and hence is no longer recommended as a first- or second-line treatment.[19][20][21][22] Flutamide is safe and effective.[23]

- Bicalutamide: A pure antiandrogen.[24][25][26] It is effective similarly to flutamide but is much safer as well as better-tolerated.[24][25][26]

- Birth control pills that consist of an estrogen, usually ethinylestradiol, and a progestin are supported by the evidence.[23][1] They are functional antiandrogens. In addition, certain birth control pills contain a progestin that also has antiandrogenic activity.[27] Examples include birth control pills containing cyproterone acetate, chlormadinone acetate, drospirenone, and dienogest.[27][21]

- Finasteride and dutasteride: 5α-Reductase inhibitors.[21] They inhibit the production of the potent androgen DHT.[21] A meta-analysis showed inconsistent results of finasteride in the treatment of hirsutism.[23]

- GnRH analogues: Suppress androgen production by the gonads and reduce androgen concentrations to castrate levels.

- Metformin: Antihyperglycemic drug used for diabetes mellitus and treatment of hirsutism associated with insulin resistance (e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome). Metformin appears ineffective in the treatment of hirsutism, although the evidence was of low quality.[23]

- Eflornithine: Blocks putrescine that is necessary for the growth of hair follicles

In cases of hyperandrogenism specifically due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia, administration of glucocorticoids will return androgen levels to normal.

Other methods

- Epilation

- Waxing

- Shaving

- Laser hair removal

- Electrology

- Lifestyle change, including reducing excessive weight and addressing insulin resistance, may be beneficial. Insulin resistance can cause excessive testosterone levels in women, resulting in hirsutism.[28] One study reported that women who stayed on a low calorie diet for at least six months lost weight and reduced insulin resistance. Their levels of Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) increased, which reduced the amount of free testosterone in their blood. As expected, the women reported a reduction in the severity of their hirsutism and acne symptoms.

See also

- Ferriman-Gallwey score

- Petrus Gonsalvus

- Androgenic hair

- Pubic hair

- Hypertrichosis

- Hair removal

- Laser hair removal

- Bearded lady

- Trichophilia

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

References

- Barrionuevo, P; Nabhan, M; Altayar, O; Wang, Z; Erwin, PJ; Asi, N; Martin, KA; Murad, MH (1 April 2018). "Treatment Options for Hirsutism: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 103 (4): 1258–1264. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-02052. PMID 29522176.

- "Merck Manuals online medical Library". Merck & Co. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- Sachdeva S (2010). "Hirsutism: Evaluation and Treatment". Indian J Dermatol. 55 (1): 3–7. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.60342. PMC 2856356. PMID 20418968.

- Barth JH, Catalan J, Cherry CA, Day A (September 1993). "Psychological morbidity in women referred for treatment of hirsutism". J Psychosom Res. 37 (6): 615–9. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(93)90056-L. PMID 8410747.

- Jackson J, Caro JJ; Caro G, Garfield F; Huber F, Zhou W; Lin CS, Shander D & Schrode K (2007). the Eflornithine HCl Study Group. "The effect of eflornithine 13.9% cream on the bother and discomfort due to hirsutism". International Journal of Dermatology. 46 (9): 976–981. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03270.x. PMID 17822506.

- Blume-Peytavi U, Hahn S. "Medical treatment of hirsutism. Dermatol Ther. 2008 Sep-Oct; 21(5): 329-39. Review". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Azziz R. (May 2003). "The evaluation and management of hirsutism". Obstet Gynecol. 101 (5 pt 1): 995–1007. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02725-4. PMID 12738163.

- Blume-Peytavi U, Gieler U, Hoffmann R, Shapiro J (2007). "Unwanted Facial Hair: Affects, Effects and Solutions". Dermatology (Basel). 215 (2): 139–146. doi:10.1159/000104266. PMID 17684377.

- Somani N, Harrison S, Bergfeld WF (2008). "The clinical evaluation of hirsutism". Dermatol Ther. 21 (5): 376–91. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00219.x. PMID 18844715.

- Unluhizarci K, Kaltsas G, Kelestimur F (2012). "Non polycystic ovary syndrome-related endocrine disorders associated with hirsutism". Eur J Clin Invest. 42 (1): 86–94. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02550.x. PMID 21623779.

- Chellini PR, Pirmez R, Raso P, Sodré CT (2015). "Generalized Hypertrichosis Induced by Topical Minoxidil in an Adult Woman". Int J Trichology. 7 (4): 182–3. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.171587. PMC 4738488. PMID 26903750.

- Dawber RP, Rundegren J (2003). "Hypertrichosis in females applying minoxidil topical solution and in normal controls". J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 17 (3): 271–5. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00621.x. PMID 12702063.

- Sachdeva, Silonie (2010). "Hirsutism: Evaluation and treatment". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 55 (1): 3–7. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.60342. PMC 2856356. PMID 20418968.

- Ferriman D, Gallwey JD (November 1961). "Clinical assessment of body hair growth in women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 21 (11): 1440–7. doi:10.1210/jcem-21-11-1440. PMID 13892577.

- Di Fede G, Mansueto P, Pepe I, Rini GB, Carmina E (2010). "High prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in women with mild hirsutism and no other significant clinical symptoms" (PDF). Fertil. Steril. 94 (1): 194–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.056. hdl:10447/36367. PMID 19338993.

- Karakurt F, Sahin I, Güler S, et al. (April 2008). "Comparison of the clinical efficacy of flutamide and spironolactone plus ethinyloestradiol/cyproterone acetate in the treatment of hirsutism: a randomised controlled study". Adv Ther. 25 (4): 321–8. doi:10.1007/s12325-008-0039-5. PMID 18389188.

- Somani N, Turvy D (2014). "Hirsutism: an evidence-based treatment update". Am J Clin Dermatol. 15 (3): 247–66. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0078-4. PMID 24889738.

- Bentham Science Publishers (September 1999). Current Pharmaceutical Design. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 712–717.

- Giorgetti R, di Muzio M, Giorgetti A, Girolami D, Borgia L, Tagliabracci A (2017). "Flutamide-induced hepatotoxicity: ethical and scientific issues". Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 21 (1 Suppl): 69–77. PMID 28379593.

- Adam Ostrzenski (2002). Gynecology: Integrating Conventional, Complementary, and Natural Alternative Therapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2761-7.

- Ulrike Blume-Peytavi; David A. Whiting; Ralph M. Trüeb (26 June 2008). Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 181–, 369–. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7.

- Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1196, 1208. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2.

- van Zuuren, Esther J; Fedorowicz, Zbys; Carter, Ben; Pandis, Nikolaos (2015-04-28). "Interventions for hirsutism (excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD010334. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010334.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6481758. PMID 25918921.

- Williams H, Bigby M, Diepgen T, Herxheimer A, Naldi L, Rzany B (22 January 2009). Evidence-Based Dermatology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 529–. ISBN 978-1-4443-0017-8.

- Erem C (2013). "Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment". Acta Clinica Belgica. 68 (4): 268–74. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796.

- Müderris II, Bayram F, Ozçelik B, Güven M (February 2002). "New alternative treatment in hirsutism: bicalutamide 25 mg/day". Gynecological Endocrinology. 16 (1): 63–6. doi:10.1080/gye.16.1.63.66. PMID 11915584.

- Ekback, Maria Palmetun (2017). "Hirsutism, What to do?" (PDF). International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolic Disorders. 3 (3). doi:10.16966/2380-548X.140. ISSN 2380-548X.

- Taylor SI, Dons RF, Hernandez E, Roth J, Gorden P (December 1982). "Insulin resistance associated with androgen excess in women with autoantibodies to the insulin receptor". Ann. Intern. Med. 97 (6): 851–5. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-97-6-851. PMID 7149493.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up hirsutism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |