Hapton, Lancashire

Hapton /ˈhæptən/ is a village and civil parish in Lancashire, England, 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Burnley, with a railway station on the East Lancashire Line. At the United Kingdom Census 2011, it had a population of 1,979.[1][2]

| Hapton | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Shuttleworth Hall | |

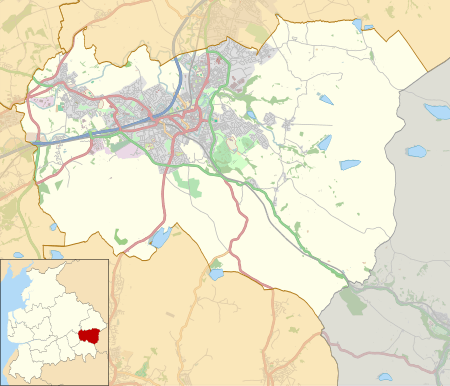

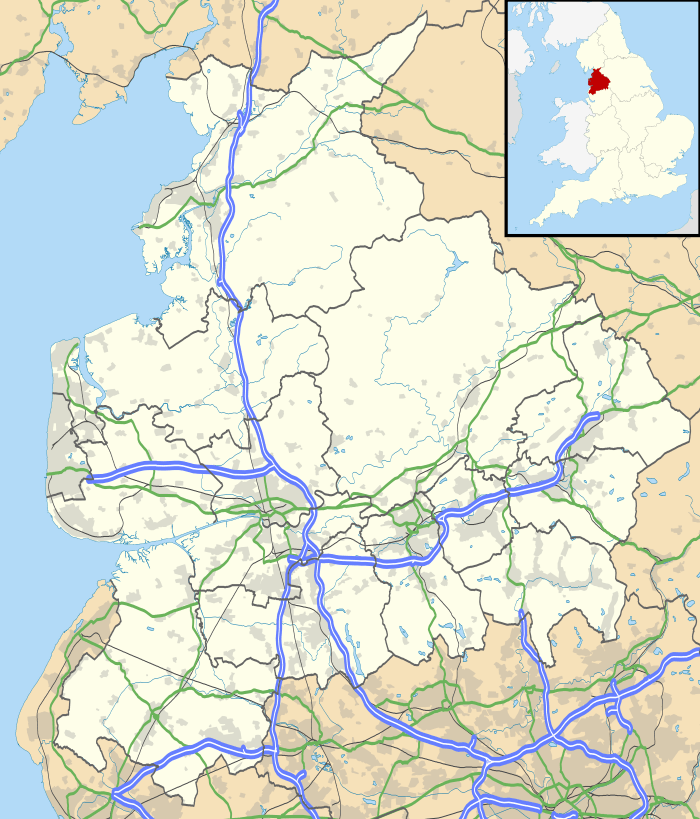

Hapton Shown within Burnley Borough  Hapton Location within Lancashire | |

| Area | 4.79 sq mi (12.4 km2) [1] |

| Population | 1,979 (2011) [1] |

| • Density | 413/sq mi (159/km2) |

| OS grid reference | SD792315 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BURNLEY |

| Postcode district | BB11; BB12 |

| Dialling code | 01282 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

The parish adjoins the Burnley parishes of Dunnockshaw, Habergham Eaves and Padiham and Lowerhouse area of Burnley, the Hyndburn parish of Altham and Huncoat area of Accrington and the Loveclough area of Rossendale.

The Leeds and Liverpool Canal and M65 motorway both pass through the village.[3][4]

History

The name Hapton is thought to have been derived from the Old English words hēap and tūn meaning the enclosure on the hill.[5]

The civil parish of Hapton is thought to be the amalgamation of three medieval manors. Hapton is linked to the original castle and village that would later develop near it. To the northwest lies Shuttleworth, thought to be the origin of the family better known at Gawthorpe Hall. The third manor was called Birtwistle and its location is uncertain, but has been suggested to have been near the site of Hapton Tower. The ancient township extended from the River Calder in the north, over the Hameldon Hills to the Forest of Rossendale in the south.[6][7]

The castle of Hapton once stood on the eastern side of Castle Clough, on the edge of a precipitous slope. Nothing is known of its origin. Further up the hill in Hapton Park, however, Hapton Tower was constructed about 1510 by Sir John Towneley (1473-1540) and was inhabited until 1667. The tower was a large square building about 20 feet (6.1 m) high with, on one side, the remains of three round towers with conical bases. It reportedly had two main entrances opposite each other. Both castle and tower were in ruins after the Restoration and today hardly anything remains of either. The only masonry of the castle now visible is a length of wall about 4 yards (3.7 m) long and 4.5 feet (1.4 m) thick and four courses high under two trees.[8]

From the Haptons the land passed to the de Leghs, when John de Hapton's daughter Cecilia married Richard de Legh in 1205. In the 12th century part of the manor was granted to William de Arches by Robert de Lacey.[9] In 1328 Gilbert de la Legh, the manager of the cattle farms in the forests, purchased the manor of Hapton and in 1356 his grandson, also called Gilbert acquired Birtwistle. His son John would marry Cecilia one of the co-heirs of Towneley Hall and their grandson John Towneley would later take control of all three manors.[6] In 1482, Sir John Towneley succeeded to the estates at the age of nine, when his father, also called Richard, died of wounds obtained during the capture of Berwick Castle.[10][9] He was married to Isabella Pilkington, the daughter of his guardian and later served as a soldier, being awarded a knighthood in 1497. With Royal permission he enclosed the manors of Towneley and Hapton, which he connected with the illegal enclosure of Horelaw Hill.[9] After the King's commissioners re-let the Forest of Rossendale to local farmers in 1507, Towneley in 1514 enlarged his park at Hapton to embrace 1100 Lancashire acres (2,000 acres (810 ha), about half of the township[11]) making it the second largest in historic Lancashire after that of the Earl of Derby at Knowsley.[12] An astute businessman he bought land, corn mills and corn tithes. He was High Sheriff of Lancashire in 1532.[8] His enclosure of this land seems to have made him unpopular, as an old local legend claims that his ghost haunts the hills.[10]

In his will dated 1627, Richard Towneley (1566-1628) left all his armour at Whalley to his son Richard. The will of Richard's wife Jane, dated 1633, provides the last recorded instance of the Towneleys at Hapton Tower.[8] Parts of the Tower are thought to have been incorporated into other buildings including Dyneley Hall in Cliviger, Browsholme Hall in Bowland and closer to the site at Watson Laithe Farm.[13]

By 1661 the lower part of the Park, north of the Tower extending to Habergham Brook, had been divided into large enclosures and these were subsequently divided into smaller ones that are still worked by today's farmers.[14] The land would remain with the Towneley estate, descending to Caroline Louisa, eldest daughter and co-heir of Colonel Charles Towneley and wife of Montagu Bertie, 7th Earl of Abingdon, who put 2,500 acres in Hapton up for sale in 1923.[15]

Shuttleworth has been occupied since at least the 14th-century. Henry de Shuttleworth died before 1325 holding lands in Shuttleworth of John son and heir of Edmund Talbot. The estate was purchased by the Starkies of Huntroyde Hall in 1734.[6] Shuttleworth Hall is about 1 mile (1.6 km) north-west of the town along the A6068 road toward Padiham. The house dates from 1639 and is a working farmhouse.[16]

Manchester Road appears on a map of 1661, and is likely part of an old route from Padiham over the moor to Haslingden. Although the Leeds and Liverpool Canal opened to Burnley in 1801, the stretch from Hapton to Blackburn was not completed until 1810 and it was 1816 before it connected to Liverpool. A Wharf was situated near the Hapton Bridge presumably to serve Padiham.[17] Accrington Road was the last of the Turnpike trust roads to be built in the local area in 1827.[18] The Castle Clough Works was established as a cotton spinning mill in 1792, where the old road to Shuttleworth crosses Castle Clough Brook, possibly the site of an earlier corn mill.[19]

The present village of Hapton is largely a product of the Industrial revolution. By the time of first Ordnance Survey map of the area, published in the 1840s, tram roads cross Stone Moor to the north, connecting the Wharf to collieries there, with more coal mines evident near the castle site. The Castle Clough Works was labelled as a dye works, but the rest of the township is still rural.[20] The Hapton Chemical Works was established by Riley and Smalley on the northern side of the canal and east side of Manchester Road in 1842 to provide chemical products for the textile trade. It was taken over by William Blythe by 1915.[19]

Although the East Lancashire railway line was constructed through the township in 1848, the railway station didn't open until the 1860s.[21] Perseverance Mill was built for John Simpson in 1867 and had an attached magneto works.[19] In 1888, Walter and Joseph Simpson established an Electrical Engineering company in Hapton called Simpson Bros. They specialised in the electrification of cotton mills and to promote the new business they installed three electric street lights, making Hapton the first village in Britain with electric lighting.[22] By the 1890s about a dozen streets of terraced houses extended from the mill, along Manchester Road to the station. The chemical factory covered approximately the same area as the village and had its own sidings.[23] Another weaving shed, Robert Walton’s Hapton Mill, was erected on the canal in 1905-6 and there was also Mathers Brick & Tile Works, the site later occupied by Lucas Industries and redeveloped for residential use in the 1990s. The only inn in Hapton before 1848 was the Towneley Arms which was situated in a no longer extant building on the north-east corner of the Lane Ends road junction. The Hapton Inn, across Accrington Road was established in the later 1800s.[19] A schoolhouse is also existed in 1848, on Manchester Road, then in an isolated position north of Lane ends.[24] St Margaret's Church was founded in 1914,[25] with Church of England services previously held in the schoolroom.[6]

By 1931, although housing in the village had approximately doubled, only the Church, vicarage, new school, recreation ground and a handful of houses existed south of the railway. However Lane Ends, on the Burnley Accrington Road had developed into a hamlet.[26] By 1961 semi-detached housing had extended along Manchester Road to Lane Ends.[27]

Geography

At the southern end of the parish are the Hameldon Hills, the summits of which attain 1,305 feet (398 m) and 1,343 feet (409 m). On the western side Castle Clough Brook runs north through a significant valley to join the Calder at Eaves Barn, however it is Shorten Brook further west that forms the actual boundary. On the eastern side New Barn Clough also flows north to join Habergham Brook, which along with Hapton Clough forms Green Brook at Spa Wood. In the centre a number of small streams combine to form Shaw Brook, which flows on the eastern side of the village and joins Green Brook just before its confluence with the Calder in Padiham.[6][28]

The underlying geology of the Hapton area consists of Lower Westphalian coal measures of the Carboniferous era, while the hills are formed of Carboniferous sandstones, ranging from millstone grits to finer grained stone such as the Dyneley Knott flags and the Dandy Mine Rock. The drift cover consists primarily of glacial till deposits, which cause poor-drainage soils, meaning the grassland is prone to reed growth.[29] A fault known as the Deerplay fault runs in a north-westerly direction under the eastern side of the parish toward Lowerhouse.[30]

There is a Site of Biological Importance at Mill Hill, Castle Clough Woods. There are many native and visiting varieties of birds, plants and animals. In addition to UK common species, green and lesser-spotted woodpecker, willow tit, yellow wagtail, woodcock and herons have all been spotted in the area. Water vole, newt and frog can be found on the steeper-sided river embankments and in large marshy wet areas by the stone bridge at the ford known as Castle Clough South and Childers Green. Bluebells grow in abundance. The entire area was classed as an area of Biological Heritage to be protected under Lancashire County Council's Local Plan for Burnley. There is free parking at Mill Hill Picnic area, about 27 yards (25 m) upstream of the ford.[31]

The Burnley Way passes through the parish, passing Shuttleworth and following Castle Clough and the part of the old road to Haslingden as it climbs over Hameldon to Clow Bridge.[32]

Governance

Hapton was once a township in the ancient parish of Whalley. This became a civil parish in 1866, forming part of the Burnley Rural District from 1894 (until 1974). However, in 1894, the Padiham Green area of the parish transferred to Padiham and Clowbridge to Dunnockshaw.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] There were further boundary changes in 1935 when the parish lost another small area to Padiham but gained a detached part of Dunnockshaw.[33] 2004 saw the parish loose more territory in the north to Padiham, with an area in Lowerhouse transferred to Burnley.[34]

The village gives its name to the Hapton with Park ward of the Borough of Burnley, which also includes the eastern areas of Padiham.[35] In recent years this ward has shown high levels of support for the British National Party, electing a BNP councillor in 2003, 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2008. After the 2010 elections, the borough's only remaining BNP councillors were those elected by this ward.[36] Sharon Wilkinson lost the final seat in 2012, a decade since the far-right group were first elected to the council.[37]

Economy

On the eastern side of the parish a colliery began in 1853 at Spa Wood, this would develop into a significant enterprise known as Hapton Valley Colliery, which would survive to be Burnley’s last deep mine, operating until 1982.[38] By the 1890s a tram road connected it to Porters Gate Colliery in the southeast and Barclay Hills Colliery in the northeast and ultimately to a coal yard on the canal at Gannow in Burnley.[23][39]

A number of smaller quarries on the hills south of the village grown by 1886 into the Hameldon Quarries when Henry Heys and Co took over the operation. It supplied large quantities of flagstones for the construction of mills in Burnley and Padiham. At that time tram roads connected the main site to another at Snipe Rake and to a facility at Park Gate Farm. These quarries ceased operation in 1909, but extensive remains are still exist. Another on the canal west of the village (Hapton Hall) was worked until 1914.[39]

During World War II the Government funded the construction of plant for Magnesium Elektron at Pollard Moor to produce metals for the aircraft industry. It closed afterward, and was later occupied by Hepworth Building Products.[39] Since 2010, with the construction of a new bridge over the canal, the site has been redeveloped into the Burnley Bridge Business Park. It neighbours the Network 65 business park, developed in the 2000s, both connecting to junction 9 on the M65 motorway.[40][41]

The William Blythe factory, which at its peak employed 1,000 people, closed in 2006. Ownership of the 38-acre (15 ha) site passed to multi-national Synthomer PLC (then Yule Catto), who funded work to remediate the land for future housing use.[42]

At the time of 2011 census only 14 people where listed as long-term unemployed in the parish, with the most common employment sectors being manufacturing, retail, health and education.[1]

People

- James Astin - footballer at Burnley F.C.

- Simon Danczuk - Member of Parliament for Rochdale from 2010

- Brian Miller - footballer and manager at Burnley F.C.

Media gallery

Hapton Bridge on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal

Hapton Bridge on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal The site of Hapton Castle on the edge of Castle Clough

The site of Hapton Castle on the edge of Castle Clough The Hapton Inn at Lane Ends, where Accrington Road becomes Burnley Road

The Hapton Inn at Lane Ends, where Accrington Road becomes Burnley Road Archaeological excavation at the site of Hapton Tower

Archaeological excavation at the site of Hapton Tower

Met Office north-west England weather radar on Hambledon Hill

Met Office north-west England weather radar on Hambledon Hill

References

Notes

- The old township boundary with Padiham followed the River Calder and its tributary Green Brook.[20]

- The old township boundary with Dunnockshaw broadly followed Limy Water and is today beneath Clowbridge Reservoir.[20]

Citations

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Hapton Parish (1170214985)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Office for National Statistics : Census 2001 : Parish Headcounts : Burnley Retrieved 4 February 2010

- "Burnley canal to get £27,000 upgrade". Lancashire Telegraph. Newsquest Media Group. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- "Hapton - Leeds and Liverpool Canal - A Virtual Trip 59". Pennine Waterways. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1922). The place-names of Lancashire. Manchester University Press. p. 80. OCLC 82106091.

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John, eds. (1911), The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster Vol 6, Victoria County History, - Constable & Co, pp. 507–12, OCLC 832215477

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey (PDF), Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 18

- Leslie Irving Gibson (1977). Lancashire Castles and Towers. Clapham, North Yorkshire: Dalesman Books. p. 25.

- John A. Clayton (2007). The Lancashire Witch Conspiracy: Histories and New Discoveries of the Pendle Witch Trials. Barrowford Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780955382123.

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 9

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, pp. 4, 17

- Tracing the Towneleys (PDF), Towneley Hall Society, 2004, p. 8, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2017, retrieved 3 August 2017

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 16

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 19

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, pp. 12–13

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Hartwell, Clare (revision) (2009). The Buildings of England – Lancashire: North. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-300-12667-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 13

- Bennett, Walter (1949), The History of Burnley, 3, Burnley Corporation, p. 151, OCLC 220326580

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 21

- Lancashire and Furness (Map) (1st ed.). 1 : 10,560. County Series. Ordnance Survey. 1848.

- East Lancashire's Historical Community Stations - Hapton (PDF), Community Rail Lancashire Ltd, retrieved 21 January 2018

- Brown, Richard; Anthony, Barry (2017), The Kinetoscope: A British History, John Libbey Publishing, p. 166, ISBN 978-0861967308

- Lancashire and Furness (Map) (1st ed.). 1:2,500. County Series. Ordnance Survey. 1893.

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 22

- "St Margaret Church of England, Hapton", Burnley, GENUKI, retrieved 21 January 2018

- Lancashire and Furness (Map) (1st ed.). 1:2,500. County Series. Ordnance Survey. 1931.

- Lancashire and Furness (Map) (1st ed.). 1:2,500. County Series. Ordnance Survey. 1961.

- "103" (Map). Blackburn & Burnley (C2 ed.). 1:50,000. Landranger. Ordnance Survey. 2006. ISBN 978-0-319-22829-6.

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 4

- E Hough (2004), Geology of the Burnley area, British Geological Survey, p. 20

- "Burnley Borough Council » Local Plan » Locally Important Nature Conservation Sites". Burnley.devplan.org.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- MKH Computer Services Ltd. "Burnley Way — LDWA Long Distance Paths". ldwa.org.uk. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Hapton Tn/CP through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Burnley (Parishes) Order 2014" (PDF). Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. 27 January 2004. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Hapton with Park". Ordnance Survey Linked Data Platform. Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Burnley Borough Council Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010

- "Live election results: Burnley". Lancashire Telegraph. Newsquest Media Group. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Hapton Valley Colliery". Mines Database. Northern Mine Research Society. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Hapton Heritage - A Landscape History and Village Survey, Bluestone Archaeology, 2013, p. 20

- Peter Magill (24 March 2010). "Bridge go ahead unlocks Burnley industrial park". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Peter Magill (5 October 2008). "New Hapton business park could lead to 100 new jobs". Lancashire Telegraph. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Hapton chemical site is cleaned". Lancashire Telegraph. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hapton, Lancashire. |