Hamamatsu Castle

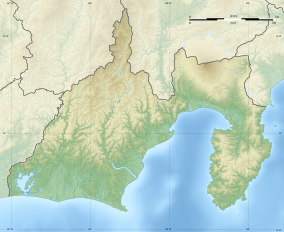

Hamamatsu Castle (浜松城, Hamamatsu-jō) is a replica hirayama-style Japanese castle. It was the seat of various fudai daimyō who ruled over Hamamatsu Domain, Tōtōmi Province, in what is now central Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan under the Edo period Tokugawa shogunate.[1] It is also called Shusse Castle (出世城, Shusse-jō).

| Hamamatsu Castle | |

|---|---|

浜松城 | |

| Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan | |

Keep of Hamamatsu Castle | |

Hamamatsu Castle  Hamamatsu Castle | |

| Coordinates | |

| Type | Japanese castle |

| Height | Three stories |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Reconstructed, serves as a museum |

| Site history | |

| Built | Circa 1532, rebuilt 1958 |

| Built by | Imagawa clan |

| Materials | Wood, stone |

Background

Hamamatsu is at the edge of Mikatagahara plateau in the center of Tōtōmi Province, and was from ancient times a post station on the Tōkaidō highway connecting Kyoto with the eastern provinces of Japan. During the late Muromachi and Sengoku period, this area came under the control of the Imagawa clan, a powerful warlord from Suruga Province. It is uncertain when the original Hamamatsu Castle was constructed; however, it appears that a fortification was built on what is now the Hamamatsu Tōshō-gū, east of the present castle, by Imagawa Sadatsuke, the fourth head of the Enshū Imagawa clan from around 1504–1520. The early castle was called Hikuma Castle (引馬城 or曳馬城, Hikuma-jō) and was entrusted to Imagawa retainer Iio Noritsura. After the fall of Imagawa Yoshimoto at the 1560 Battle of Okehazama, Iio Tsuratatsu rebelled against Imagawa Ujinao, but was defeated. However, the greatly weakened Imagawa clan was unable to withstand the combined forces for Tokugawa Ieyasu from Mikawa and Takeda Shingen from Kai. The former Imagawa territories in Tōtōmi were divided between the Tokugawa and Takeda in 1568. In December of the same year Tokugawa Ieyasu laid siege to Hikuma Castle and took it from Otazu no kata. He relocated his headquarters from Okazaki Castle to Hamamatsu in 1570, and started construction of a new castle on a site which partially overlapped that of the original Hikuma Castle.

Layout

Hamamatsu Castle was approximately 500 meters north-south by 450 meters east-west. The location has few natural barriers, but the castle utilizes the natural slope of the Mikatagahara plateau, with the donjon at the highest point in the northwest. To east was the inner bailey, followed by the second bailey and third bailey roughly in a straight line to the southeast. The stone walls were constructed in the nozura-zumi style using unshaped stones, with the ruins of the fortifications of the original Hikuma Castle also forming part of the outer defenses.

History

Tokugawa Ieyasu spent 17 years at Hamamatsu Castle, from age 29 to 45. The Battle of Anegawa, Battle of Nagashino, and Battle of Komaki and Nagakute were all fought when Hamamatsu was his seat. After his defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara, Ieyasu forced to retreat here for what he thought would be his final stand. However, the tide later turned for Ieyasu and he survived. He renamed Hikuma Castle "Hamamatsu Castle" in 1577.

Ieyasu relocated to Sunpu Castle in 1586, entrusting Hamamatsu Castle to Horio Yoshiharu, who was followed by his son Horio Tadauji. Under Horio Yoshiharu, the castle was renovated in line with contemporary advances in stone ramparts, and was expanded in size. Contemporary records indicate that the castle was never built with a tenshukaku-style keep. Throughout its history, a two-story yagura located within the second bailey served as a substitute keep.

After the Battle of Sekigahara, the Horio clan was relocated to Izumo Province and Hamamatsu was briefly ruled by Tokugawa Yorinobu, followed by a succession of fudai daimyō through the remainder of the Edo period. Assignment to Hamamatsu was considered a very prestigious appointment due to the castle's association with Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. Most of the 25 daimyō who ruled Hamamatsu were assigned to Hamamatsu for only a short period, before being transferred to another domain, usually with a higher kokudaka ranking. Many also went on to hold high offices within the shogun administration, including five rōjū, two Kyoto Shoshidai, two Osaka jōdai and four Jisha-bugyō. For this reason, Hamamatsu Castle gained its nickname of Shusse Castle, meaning "Castle of promotion.

With the Meiji Restoration, the remaining military structures of the castle were destroyed, outer moats filled in, and outer baileys sold off. The central portion was retained by the city of Hamamatsu as a park after World War II

In 1958, a faux donjon was constructed out of reinforced concrete on top of the original stone palisade built by Tokugawa Ieyasu. The reconstructed structure has three stories with an observatory affording a view of the Pacific Ocean at the topmost level. There is a small museum inside which houses armor and other relics of Tokugawa clan, as well as a miniature model of how the city might have looked at the start of the Edo period. Surrounding the museum is Hamamatsu Castle Park which is planted with numerous sakura trees. A large bronze statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu also stands in the park.[2]The castle was listed as one of the Continued Top 100 Japanese Castles in 2017.[3]

Notes

- Connolly, Peter (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare. New York: Routledge. pp. 213. ISBN 1-57958-116-1.

- "Statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu". TripAdvisor.

- "続日本100名城" (in Japanese). 日本城郭協会. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

References

- Schmorleitz, Morton S. (1974). Castles in Japan. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Co. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8048-1102-4.

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 200 pages. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

- Mitchelhill, Jennifer (2004). Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha. p. 112 pages. ISBN 4-7700-2954-3.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Japanese Castles 1540–1640. Osprey Publishing. p. 64 pages. ISBN 1-84176-429-9.

External links

![]()