Halasana

Halasana (Sanskrit: हलासन; IAST: halāsana), or Plough pose,[1] is an inverted asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise. Its variations include Karnapidasana with the knees by the ears, and Supta Konasana with the feet wide apart.

Etymology and origins

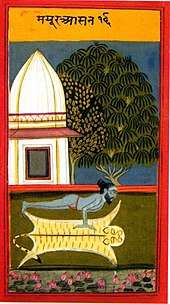

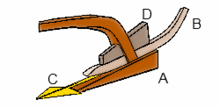

The name comes from Sanskrit हला hala, "plough" and आसन āsana, "posture" or "seat".[2] The pose is described and illustrated in the 19th century Sritattvanidhi as Lāṇgalāsana, which also means plough pose in Sanskrit.[3]

Karnapidasana is not found in the medieval hatha yoga texts. It is described independently in Swami Vishnudevananda's 1960 Complete Illustrated Book of Yoga in the Sivananda Yoga tradition, and by B. K. S. Iyengar in his 1966 Light on Yoga, implying that it may have older origins.[4][5] The name comes from the Sanskrit words karṇa (कर्ण) meaning "ears", pīḍ (पीड्) meaning "to squeeze", and āsana (आसन) meaning "posture" or "seat".[6]

Description

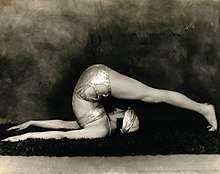

The pose is entered from Sarvangasana (shoulderstand), lowering the back slightly for balance, and moving the arms and legs over the head until the outstretched toes touch the ground and the fingertips, in a preparatory variant of the pose. The arms may then be moved to support the back into a more vertical position, giving a second variant pose. Finally, the arms may be stretched out on the ground away from the feet, giving the final pose in the shape of a traditional plough.[4]

Variations

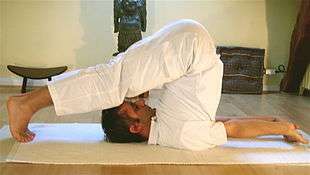

Karnapidasana (Ear pressing pose) or Raja Halasana (Royal plough pose) has the knees bent close to the head and grasped by the arms.[7]

Parsva Halasana (Sideways plough) with the body vertical, the trunk twisted to one side, and legs out straight with the feet touching the ground (to that side).[7]

Supta Konasana (Supine angle pose) has the legs as wide apart as possible, the toes on the ground;[8] the fingertips may grasp the big toes.[7]

All these variations may be performed as part of a cycle starting from Sarvangasana (Shoulderstand).[7]

Claims

Twentieth century advocates of some schools of yoga, such as B. K. S. Iyengar, made claims for the effects of yoga on specific organs, without adducing any evidence.[9][10] Iyengar claimed that this pose brought "the same" benefits as Sarvangasana, with the additional benefit of relief of backache, but unlike that pose was recommended for people with high blood pressure.[11]

Cautions

Plough pose can put significant strain on the cervical spine, which does not normally undergo this type of stress, and can cause injury if not performed properly.[12][13][14]

See also

References

- YJ Editors (28 August 2007). "Plough Pose". Yoga Journal.

- Sivananda, Swami (June 1985). Health and hatha yoga. Divine Life Society. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-949027-03-0.

- Sjoman 1999, p. 72.

- Iyengar 1979, pp. 216-219.

- Sjoman 1999, pp. 88, 92.

- Sinha, S. C. (1996). Dictionary of Philosophy. Anmol Publications. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7041-293-9.

- Mehta 1990, pp. 111–115.

- "Supta Konasana". Yogapedia. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- Newcombe 2019, pp. 203-227, Chapter "Yoga as Therapy".

- Jain 2015, pp. 82–83.

- Iyengar 1979, pp. 219-220.

- "Halasana". Yoga Journal: 7. February 1983. ISSN 0191-0965.

- Robin, Mel (May 2002). A Physiological Handbook for Teachers of Yogasana. Wheatmark. p. 516. ISBN 978-1-58736-033-6.

- Robin, Mel (2009). A Handbook for Yogasana Teachers: The Incorporation of Neuroscience, Physiology, and Anatomy Into the Practice. Wheatmark. p. 835. ISBN 978-1-58736-708-3.

Sources

- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979) [1966]. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Unwin Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1855381667.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga: The Iyengar Way. Dorling Kindersley.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2019). Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Bristol, England: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78179-661-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sjoman, Norman E. (1999) [1996]. The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-389-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

_from_Jogapradipika_1830_(detail).jpg)