Hochtief

Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft is a German construction company based in Essen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.[5] Hochtief is Germany's largest construction company and operates globally, ranking as one of the largest general construction companies in the United States through its Turner subsidiary, and in Australia through a 72.683% shareholding in CIMIC Group.[6] In 2010 it employed more than 70,000 employees across five corporate divisions. One of these, Hochtief Concessions, is a major airport operator. The others are involved with construction project planning, finance, construction and operation.[5] Work done in 2010 was €23.23 billion, with more than 80% coming from operations outside Germany.[7]

| |

| Aktiengesellschaft | |

| Traded as | FWB: HOT |

| ISIN | DE0006070006 |

| Industry | Construction |

| Founded | 1873[1] |

| Headquarters | Essen, Germany |

Key people | Marcelino Fernández Verdes (CEO and chairman of the executive board), Manfred Wennemer (Chairman of the supervisory board) |

| Products | Construction services, project management, facility management |

| Revenue | €22.631 billion (2017)[2] |

| €865.8 million (2017)[3] | |

| €420.7 million (2017)[3] | |

| Total assets | €13.348 billion (end 2017)[3] |

| Total equity | €4.26 billion (end 2010)[3] |

Number of employees | 53,890 (average, 2017)[3] |

| Parent | Grupo ACS (66.5%)[4] |

| Website | www.hochtief.com |

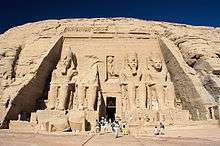

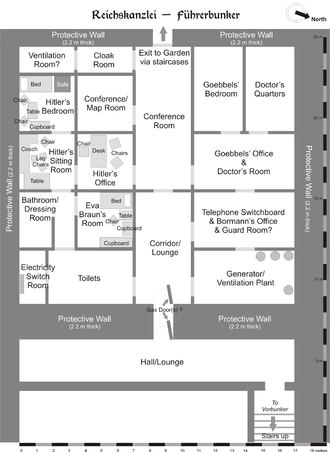

The company's history dates back to 1874 and includes engineering feats such as the transplantation of the Abu Simbel rock temples in Egypt (saving them from the rise of the River Nile caused by the Aswan High Dam),[8] and infrastructure projects like the new Athens International Airport[9] and Germany's first nuclear power plant.[10] It is also noted for its involvement with the Bauhaus movement,[11] particularly for its work at Zollverein colliery[12] and the reconstruction of the Kandinsky-Klee house in Dessau;[13] both World Heritage Sites. During World War II it deployed forced labor on construction projects.[14] It built the Führerbunker in Berlin, the scene of Adolf Hitler's suicide, as well as Hitler's home in Berghof and the Wolfsschanze headquarters.[15] More recent constructions have included Bosphorus Bridge (Turkey),[16] King Abdulaziz International Airport (Saudi Arabia),[17] and the Messeturm[18] and Commerzbank Tower[19] in Frankfurt.

In late 2010, Spanish construction company Grupo ACS, which already owned a 30 percent stake of Hochtief, launched a bid that would allow ACS to acquire an additional 20 percent stake of Hochtief. The bid was approved by the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) on 29 November 2010.[20] ACS increased its stake in Hochtief to 50.16 percent in June 2011,[21] effectively taking over control of Hochtief.

History

Early years

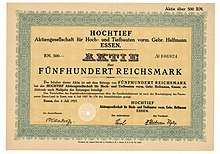

The company was probably founded in 1874 (its first mention in the local address book) as Gebrüder Helfmann, Bauunternehmer by the Kelsterbach-born brothers Philipp and Balthasar Helfmann, a lumber merchant and mechanic respectively, in Bornheim near Frankfurt am Main.[22] While Balthasar focused on the completion of construction contracts, Philipp developed the financing side of the business.[23] Their first major contract was for the University of Giessen in 1878.[24] By the 1880s the company had begun to produce its own construction materials but was still only a regional player.[25] Shortly after the death of Balthasar, Philipp converted the company into a joint stock corporation, Aktiengesellschaft für Hoch- und Tiefbauten ("Construction and Civil Engineering Corporation", though literally the "Corporation for High - Hoch and Deep - Tief Construction - Bauten).[26] A major development was the contract for the spa project in Bad Orb in 1899, with the corporation not simply erecting buildings but also to provide infrastructure like roads and gardens, to arrange the finances for the project, and to maintain some responsibilities for operating the project after its construction.[27] Also in 1899, another turnkey project, a new grain silo in Genoa, Italy, was both the firm's first international venture and its first project using reinforced concrete.[28] Philipp Helfmann died in the same year, with his son-in-law, Hans Weidmann, taking over as Chief Executive.[29]

After the Helfmann brothers

The firm grew rapidly, but was not comparable with the major German construction concerns of the era. In 1921 it attracted investment from the industrialist Hugo Stinnes[30] (described by Time as the "New Emperor of Germany" for his wealth and influence) and in 1922 the firm moved its base to Essen as part of its integration into the Stinnes group.[31] Stinnes planned to use Hochtief for all his construction projects, while the Hochtief saw an opportunity to profit from the Treaty of Versailles, organising the delivery of construction materials to France as part of German reparations for World War I.[32] Fate intervened as Stinnes died in 1924 and within a year his industrial empire collapsed, while the French occupation of the Ruhr destroyed the chance to profit from the reparations contract that had been made with the French industrialist Guy Louis Jean de Lubersac. With the help of several banks, the company (now known as Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft für Hoch- und Tiefbauten vorm. Gebrüder Helfmann) avoided insolvency. In the aftermath of the Stinnes collapse, the major utility RWE and electrical equipment producer AEG became major share-holders in Hochtief, and Hans Weidmann stepped down in 1927.[33]

A series of major construction projects ensued, including the Echelsbach Bridge (then Germany's largest single span reinforced concrete bridge[34]), the Schluchsee dam[35] and work at the Zollverein colliery. The Zollverein architects Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer seem to be influenced by the Bauhaus, one of the reasons the complex became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[12] The iconic Shaft 12 at the colliery was named after Albert Vögler, CEO of the Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG, which was owner of the colliery since 1926.[36] There was also canal work: the Moselle Canal in France[37] and the Albert Canal in Belgium.[38]

From Nazi Germany to Reconstruction

Under the Third Reich, Jewish members of the Supervisory Board were expelled under the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. The CEO, Eugen Vögler, did not join the Nazi party until 1937, however, he did offer his services to the Nazis as leader of the "Construction Industry Business Group" and took a position in the Hitler Youth. The construction business flourished under the Four year plan, with its vast public works programme, including the Autobahn network, and the industrial build-up in preparation for war, for example the construction of a new truck factory for Opel in Brandenberg. Hochtief also worked on a new centre for Nazi rallies in Nuremberg. In 1936 it moved its Essen headquarters from the Pferdemarkt to its current location in Rellinghauser Straße. As war became imminent, the company began work on the Westwall defensive network. During World War II, it later worked on the Atlantic Wall defences, and a range of infrastructure projects across German-dominated Europe. Hochtief also constructed buildings for Hitler himself, notably his Bavarian Alpine retreat, the Berghof, his Wolf's Lair headquarters in Rastenburg, and the Führerbunker in Berlin, where Hitler ultimately committed suicide.[15]

After 1939 the firm began to use forced labour extensively on its projects, as did many other German industrial concerns at the time. Hochtief's slave workers suffered from malnutrition, beating and constant abuse.[39] The consortium-led nature of construction projects obscures the firm's exact involvement, as does the destruction of many records.[14]

During the closing stages of the war, most of the company's branch offices were destroyed, and employees in the East fled the Soviet advance. The head office in Essen suffered a direct hit from a bomb in March 1945,[14] and regional offices and construction centres in Danzig, Halle, Katowice, Königsberg, Kraków, Leipzig and Magdeburg were lost as the territory they were in was allotted to Poland or the Soviet Zone of occupation. As Eugen Vögler was on the run from the new authorities, he was replaced as CEO by Artur Konrad.[40]

During the initial post-war period, a shortage of machinery, tools, and materials, as well as a dearth of new orders, hampered operations.[41] Some salvage work occurred, as well as rubble-clearance and basic repairs. One of the first, rare, major contracts was for a university hospital in Bonn, 1946–49. The introduction of the German mark in 1948 and the beginning of the Wirtschaftswunder brought more new work.[42]

Revival and international expansion

Josef Müller took over as CEO in 1950. A decision was taken to undertake more international projects, following a period of essentially domestic work after World War II. This included a series of power infrastructure works in Turkey and bridge and smelting works construction in Egypt during the early 1950s. Many projects from this period were undertaken outside of the First World, often funded from development aid budgets.[42]

A high-profile success for the company came in the 1960s, again in Egypt. The rising waters of the River Nile (a result of the construction of the Aswan High Dam) threatened the ancient Abu Simbel temples complex. The entire site was dismantled and reassembled 200 m further from the river, and 65 m higher,[8] at a cost of around US$36 million.[43]

The focus of the company began to switch away from purely construction and towards more turnkey work and service provision, for example the 1961-3 Hilton Hotel, Athens, project.[10] Most work was domestic, driven by Germany's strong economic growth, with a particular strength in power plant construction. This included the construction of the Federal Republic of Germany's first nuclear power plant, Kahl Nuclear Power Plant, near Dettingen am Main.[10] The construction contract had been awarded by AEG, which had been commissioned by the utility company RWE to build the plant. The plant began to feed its electricity to the grid in June 1961.[44] By contrast, the first East German nuclear plant, at Rheinsberg, was connected to the grid in 1966.[45]

There was also considerable transport infrastructure activity, including on the Hernandarias Subfluvial Tunnel, Argentina in the 1960s[46] and the New Elbe Tunnel in Hamburg in the 1970s[47]

By the mid-1970s, foreign work (such as the Bosporus Bridge in Turkey, completed 1974[16]) was accelerating while domestic orders were receding, according to the company's annual report of 1975. By 1980, foreign work accounted for more than 50% of Hochtief's business. A major factor was the contract for King Abdulaziz International Airport (completed 1981), the largest airport in Saudi Arabia, and the most valuable contract Hochtief had ever been involved with.[17] The architecture of the airport is highly rated aesthetically, and it has several unusual features, including Terminal Three, used only during the Hajj, reserved for pilgrims travelling to Mecca. It has a tent-shaped fibreglass roof, contains a mosque, can accommodate 80,000 travellers at once, and is believed to be the largest terminal in the world.[48]

_Frankfurt-2.jpg)

The 1980s were a difficult time financially, with less foreign work coming through; though they headed the consortium that built the Mosul Dam in Iraq from 1981–84. There was domestic growth, highlighted by the architecturally radical Messe Torhaus in Frankfurt, completed in 1984.[17] It was later involved in the construction of the Messeturm in the same city; once completed in 1991 it was Europe's tallest building.[18] In the mid-1990s, Hochtief was involved in yet another major skyscraper development in Frankfurt, the Commerzbank Tower, which overtook the Messeturm to become Europe's tallest building, losing the record to Triumph-Palace in Moscow in 2003.[19]

The 1990s brought an opportunity to expand operations in the airport management sector, as many countries privatised their airports. When Warsaw Frederic Chopin Airport needed upgrading in the early 1990s, LOT Polish Airlines was unable to afford the cost, so a complex financing arrangement was established whereby a bank would pay Hochtief two thirds of the costs to upgrade the airport, while the airline assigned to the bank the revenues from aircraft using Polish airspace for a period.[49] The company began to take responsibility for more operational aspects of projects, including service provision, financing, facility management and software development, following a concept of being a "system leader", as set out by CEO Hans-Peter Keitel. These tasks were felt to be higher up the value chain, and would help the firm shake off the slowdown that had followed the initial boom of German reunification. These concepts were notably put into action during the construction of the new Athens International Airport in the late 1990s.[50]

In 1999, Hochtief made big inroads into the United States market through its merger with Turner Corporation,[51] while in 2000 it celebrated its 125th anniversary. A part of those celebrations was the DM 1 million donation to the restoration of the Kandinsky-Klee House in Dessau, a project for which it was the general contractor. The house had been used by the Bauhaus movement as an example of a "Meisterhaus", but Nazi persecution of the Bauhaus, and subsequent neglect, had left significant damage. The house was re-opened on 4 February 2000, after a two-year restoration programme. It forms part of the UNESCO Bauhaus World Heritage Site.[13]

In May 2013, Hochtief sold its airports division to Canada's Public Sector Pension Investment Board for 1.1 billion euros.[52]

Structure and ownership

Hochtief is an Aktiengesellschaft, roughly equivalent to a public limited company in the United Kingdom. Its shares are traded on all the German stock exchanges, including the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and Börse München, using the Xetra system. Hochtief is a component of the MDAX share index.[53] The major shareholders are Grupo ACS with 61%, and Qatar Holdings LLC, with more than 10%. (This makes Hochtief a Grupo ACS subsidiary.) .[54]

As of January 2011, Hochtief has streamlined its corporate operations. The group is now divided into four divisions:[55]

- Hochtief Americas

- Hochtief Asia-Pacific

- Hochtief Europe

- Hochtief Concessions

The European division plans, develops, implements, operates and manages real estate and infrastructure facilities in Europe and in selected regions worldwide.[56]

The Asia-Pacific division includes the activities of CIMIC Group Limited (formerly known as Leighton Holdings prior to April 2015) in Australia and Asia. CIMIC does not only provide construction and construction services but is also the world's largest contract miner. The Americas division co-ordinates the United States subsidiaries Turner Construction (acquired in 1999), Flatiron Construction (acquired in 2007) and E.E. Cruz (acquired in 2010).[57]

Hochtief Concessions develops and implements concession projects. Its business areas include airports, roads, social infrastructure and further public-private partnership projects. One of its subsidiaries, Hochtief Airports, holds stakes in Athens International Airport, Düsseldorf Airport, Hamburg Airport, Sydney Airport, Budapest Airport and Rinas Mother Teresa Airport (Tirana).[58]

Timeline of notable construction projects

- 1927-1932: Zollverein colliery (Shaft XII), Essen[12]

- 1928-1929: Echelsbach Bridge, near Echelsbach, Bavaria[34]

- 1929-1931: Schluchsee Dam, Schluchsee, Black Forest[35]

- 1930-1934: Albert Canal, Belgium[38]

- 1938-1945: Projects included the Westwall and Atlantic Wall defenses, and Hitler's Berghof, Wolf's Lair and Führerbunker[15]

- 1946-1949: Bonn University Hospital, Bonn[42]

- 1952-1956: Sariyar Hydroelectric plant, Ankara, Turkey[42]

- 1958-1961: Kahl Nuclear Power Plant, Dettingen am Main[10]

- 1960-1969: Hernandarias Subfluvial Tunnel, Argentina[46]

- 1961-1963: Hilton Hotel, Athens, Greece[10]

- 1963-1968: Abu Simbel temples transplanted, Egypt[8]

- 1969-1975: New Elbe Tunnel, Hamburg[47]

- 1970-1974: Bosphorus Bridge, Turkey[16]

- 1974-1981: King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia[17]

- 1981-1984: Mosul Dam, Iraq

- 1984-1985: Messe Torhaus, Frankfurt am Main[17]

- 1988-1991: Messeturm, Frankfurt am Main[18]

- 1990-1992: Terminal One, Warsaw Airport, Poland[49]

- 1994-1996: Commerzbank Tower, Frankfurt am Main[19]

- 1996-2000: Athens International Airport, Greece[9]

- 1998-2000: Kandinsky-Klee house restoration, Dessau[13]

- 2004: Katima Mulilo Bridge, Zambia and Namibia[59]

- 2005-2008: Dnipro Stadium, Ukraine[60]

- 2007: Chacao Channel bridge construction due to commence[61]

- 2008: Opera Krakowska, Krakow, Poland[62]

- 2014–present: Expansion of King Khalid International Airport, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia[63]

Notes and references

- "HOCHTIEF Konzern > Geschichte". www.hochtief.de.

- Annual Report 2017, 21 February 2018, retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "Annual Report 2010". Hochtief. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- 4-traders. "ACS Actividades de Construccion y Servicios company : Shareholders, managers and business summary - Bolsa de Madrid: ACS - 4-Traders". www.4-traders.com.

- Hochtief investor relations website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Corporate Portrait Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Archived 22 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Hochtief annual report website. Retrieved 5 April 2010

- The rescue of Abu Simbel, 1963-1968, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- System leadership and the public-private partnership from 1990 onwards, Page 2/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- From the master-builder to the construction corporation (1966-1989), Page 2/3, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Sponsoring: Close links with the Bauhaus, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Zollverein coal mine in Essen, 1929-1931, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; further information Archived 27 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine on http://www.worldheritagesite.org/ accessed 16 February 2006

- The Kadinsky-Klee House, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2005; Restoration, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; Bauhaus and its sites Archived 30 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, http://www.worldheritagesite.org/. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Politicization of the construction industry (1933-1945), Page 4/4, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Politicization of the construction industry (1933-1945), Page 3/4, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Bosphorus Bridge in Turkey, 1970-1974, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- From the master-builder to the construction corporation (1966-1989), Page 3/3, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Exhibition center tower in Frankfurt am Main, 1988-1991, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2005; Messe Tower at Structurae

- Commerzbank in Frankfurt am Main, 1994-1996, Hochtief website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; Commerzbank Tower at Structurae

- Bafin press release Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Bafin website. Retrieved 5 April 2011

- , Deutsche Welle

- The Helfmann Brothers (1873-1896), Page 1/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- The Helfmann Brothers (1873-1896), Page 2/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- The Helfmann Brothers (1873-1896), Page 4/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- The Helfmann Brothers (1873-1896), Page 5/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Establishment of the "Aktiengesellschaft", (1896-1921), Page 1/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Establishment of the "Aktiengesellschaft", (1896-1921), Page 2/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Grain store in the port of Genua, 1899-1901, Hochtief history website]. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Establishment of the "Aktiengesellschaft", (1896-1921), Page 5/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 1/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 2/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; Time magazine claim appears uncited in Hugo Stinnes article

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 3/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 4/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- The Echelsbach Bridge, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; Echelsbach Bridge at Structurae. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 5/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- The claim that Shaft 12 was named after Vögler appears unsourced on the German Wikipedia article, as live on 16 February 2006.

- Under the influence of the Stinnes Group, (1921-1933), Page 6/6, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Albert Canal in Belgium, 1930-1934, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Belle Millo, ed. (2010). Voices of Winnipeg Holocaust Survivors. Belle Millo. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-9691256-9-3.

- List of centres lost, and appointment of Konrad, taken from Reconstruction (1945-1966), Page 1/3, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006; Vögler's suicide, with date of death, appears unsourced on his German Wikipedia biography, as live on 16 February 2006.

- Reconstruction (1945-1966), Page 2/3, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Reconstruction (1945-1966), Page 3/3, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Estimated cost is given, unreferenced, in the Abu Simbel article.

- History of Nuclear Power Archived 20 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine, German Atomic Energy Forum Archived 16 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Nuclear Power in Germany, Nuclear Issues Briefing Paper 46, Jan 2009, World Nuclear Association . Retrieved 12 January 2009

- Paraná Tunnel in Argentina, 1961-1962, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 6 February 2006

- Elbe tunnel in Hamburg, 1969-1975 and 1997-2003, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- Uncited sources, King Abdulaziz International Airport article, as live on 16 February 2006

- Warsaw International Airport, 1990-1992, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 16 February 2006

- System leadership and the public-private partnership from 1990 onwards, Page 2/5, Hochtief history website. Retrieved 6 February 2006

- Press Release Turner merges with Hochtief Archived 15 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Turner website. Retrieved 5 April 2011

- Ludwig Burger (7 May 2013). "Hochtief sells airport unit to Canada's PSP Investments for $1.4 billion". Reuters.

- Key figures on Hochtief shares, Hochtief investor relations website, access 16 February 2006

- Shareholder structure, Hochtief investor relations website. Retrieved 18 August 2011

- Corporate structure, Hochtief website. Retrieved 5 April 2011

- "HOCHTIEF Group > Structure > HOCHTIEF Europe". www.hochtief.com.

- Hochtief Americas, Hochtief website. Retrieved 5 April 2011

- Hochtief concessions. Retrieved 5 April 2011

- Website of Dr. Klaus Dierks , first Deputy Minister for Works, Transport and Communication in independent Namibia, involved in the planning and negotiations for the bridge. Retrieved 15 February 2005.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- This date was given, unreferenced, in the Chacao Channel bridge article.

- The Opera Krakowska: "About us" Access date: 9 July 2009

- Webb, Alex (30 June 2015). "Hochtief-Led Group Seals $1.5 Billion Riyadh Airport Contract". bloomberg.com. Retrieved 7 April 2016.