HMS Simoom (P225)

HMS Simoom was a third-batch S-class submarine built for the Royal Navy during World War II. She was laid down on 14 July 1941 and launched on 12 October 1942.

Simoom on the surface | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Simoom |

| Ordered: | 2 September 1940 |

| Builder: | Cammell Laird, Birkenhead |

| Laid down: | 14 July 1941 |

| Launched: | 12 October 1942 |

| Commissioned: | 30 December 1942 |

| Fate: | Sunk, 4–19 November 1943 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | S-class submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 217 ft (66.1 m) |

| Beam: | 23 ft 9 in (7.2 m) |

| Draught: | 14 ft 8 in (4.5 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: | 6,000 nmi (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) (surfaced); 120 nmi (220 km; 140 mi) at 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph) |

| Test depth: | 300 ft (91.4 m) (submerged) |

| Complement: | 48 |

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Armament: |

|

After an initial patrol off Norway, Simoom sailed to Gibraltar, then to Algiers, French North Africa. From there, she conducted four patrols and attacked several ships, but only sank an Italian destroyer. Simoom then visited several ports in the eastern Mediterranean, then departed Port Said for a patrol off Turkey. She did not return from this patrol, and it is considered most likely that she hit a mine and sank. Her wreck was discovered in 2016 off Tenedos, Turkey.

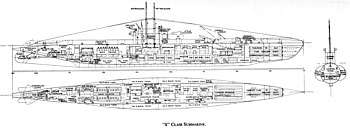

Design and description

The S-class submarines were designed to patrol the restricted waters of the North Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. The third batch was slightly enlarged and improved over the preceding second batch of the S class. The submarines had a length of 217 feet (66.1 m) overall, a beam of 23 feet 9 inches (7.2 m) and a draught of 14 feet 8 inches (4.5 m). They displaced 865 long tons (879 t) on the surface and 990 long tons (1,010 t) submerged.[1] The S-class submarines had a crew of 48 officers and ratings. They had a diving depth of 300 feet (91 m).[2]

For surface running, the boats were powered by two 950-brake-horsepower (708 kW) diesel engines, each driving one propeller shaft. When submerged each propeller was driven by a 650-horsepower (485 kW) electric motor. They could reach 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) on the surface and 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) underwater.[3] On the surface, the third-batch submarines had a range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) and 120 nmi (220 km; 140 mi) at 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph) submerged.[2]

The boats were armed with seven 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes. A half-dozen of these were in the bow, and one external tube was mounted in the stern. They carried six reload torpedoes for the bow tubes for a total of thirteen torpedoes. Twelve mines could be carried in lieu of the internally stowed torpedoes. They were also armed with a 3-inch (76 mm) deck gun.[4] It is uncertain if Simoom was completed with a 20-millimetre (0.8 in) Oerlikon light AA gun or had one added later. The third-batch S-class boats were fitted with either a Type 129AR or 138 ASDIC system and a Type 291 or 291W early-warning radar.[5]

Construction and career

HMS Simoom was a third-group S-class submarine and was ordered by the British Admiralty on 2 September 1940. She was laid down in the Cammell Laird Shipyard in Birkenhead on 14 July 1941 and launched on 12 October 1942.[6] On 27 December 1942, Simoom, under the command of Lieutenant Christopher Henry Rankin, sailed from the shipbuilding yards to Holy Loch, where she was commissioned into the Royal Navy three days later.[6][7] The simoom is a hot dry desert wind; Simoom was the fifth Royal Navy ship with this name.[8]

After training, Simoom departed port on 15 February 1943 for a patrol off Norway, providing protection to Arctic Convoys to and from ports in Northern Russia. Her patrol was uneventful, and she returned to Lerwick on 11 March. After having one of her propellers changed, Simoom sailed to Gibraltar, then on to Algiers, where she arrived on 24 May.[7]

Algiers

On 4 June 1943, Simoom, now under the command of Lieutenant Geoffrey D. N. Milner, departed Algiers to patrol west of Sardinia and Corsica. Her patrol was again uneventful, and she returned to port on 17 June having sighted only a few aircraft and no ships.[7]

Simoom's next patrol started on 28 June, when she patrolled in the Tyrrhenian Sea to provide cover for the Allied landings in Sicily. On 13 July, she fired four torpedoes at an enemy convoy, but missed. Two days later, the submarine attacked the Italian tug Robusto with her deck gun on the surface and scored several hits, but an approaching aircraft forced her to break off the action and submerge. Simoom then ended her patrol on 22 July.[7]

Simoom again departed Algiers on 4 August for a patrol in the Gulf of Genoa; on 8 August, she unsuccessfully attacked a merchant ship with three torpedoes. The next day, the boat sighted the Italian cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi along with several light cruisers and destroyers; she fired three torpedoes at Giuseppe Garibaldi, but again missed. The torpedoes, however, instead sank the Italian Oriani-class destroyer Vincenzo Gioberti (it) with the loss of 171 men.[9] Simoom was then counter-attacked with depth charges, but she evaded damage and returned to Algiers on 13 August after having been recalled.[7]

On 3 September, the submarine commenced another patrol in the western Mediterranean, with orders to act as a directional radio beacon during Operation Avalanche, the Allied landings near Salerno. Simoom's participation was not necessary, and she did not carry out the operation. On 15 September, the boat launched two torpedoes at the German transport KT 11, but missed. She then ended her patrol in Algiers on 22 September.[7]

Sinking

From 3 to 17 October 1943, Simoom sailed to Port Said, passing through Malta, Beirut, and Haifa. She underwent repairs to her battery, then departed for a patrol between Naxos and Mikonos, Greece on 2 November.[10] The submarine did not return to Beirut on 19 November as planned, and was declared overdue on the 23rd. Simoom may have been sunk by the German submarine U-565 on 15 November. German radio broadcast at this date claimed that a submarine was sunk in the Aegean with some members of the crew rescued.[10] The incident was never confirmed since the Germans were not able to visibly identify the enemy submarine, which it hit with a Zaunkönig torpedo.[11] However, this was considered unlikely; post-war studies concluded that the most probable cause of her sinking is that she had hit a mine on 4 November in a new minefield off Donoussa. Her wreck was discovered in 2016 off Tenedos, Turkey. Simoom's starboard (right) hydroplanes showed extensive damage, and it is now considered most likely that she hit a mine while on the surface.[7][12]

Out of 15 torpedoes fired by Simoom during her career, all missed their intended targets, but three torpedoes hit and sank the Italian destroyer Vincenzo Gioberti instead.[7]

Summary of raiding history

During her service with the Royal Navy, Simoom sank one Italian destroyer of 1,685 tons.[7]

| Date | Name of ship | Tonnage | Nationality | Fate and location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 August 1943 | Vincenzo Gioberti | 1,685 | Torpedoed and sank at 44°04′N 09°32′E |

Citations

- Akermann, p. 341

- McCartney, p. 7

- Bagnasco, p. 110

- Chesneau, pp. 51–52

- Akermann, pp. 341, 345

- Akermann, p. 340

- "HMS Simoom (P 225)". uboat.net. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Akermann, p. 348

- Akermann, p. 351

- Heden, Karl Erik (2006). Sunken Ships, World War II: U.S. Naval Chronology Including Submarine Losses of the United States, England, Germany, Japan, Italy. Boston: Branden Books. p. 244. ISBN 0828321183.

- Paterson, Lawrence (5 March 2019). U-Boats in the Mediterranean: 1941–1944. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781510731677.

- Heden, p. 244

References

- Akermann, Paul (2002). Encyclopaedia of British Submarines 1901–1955 (reprint of the 1989 ed.). Penzance, Cornwall: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904381-05-1.

- Bagnasco, Erminio (1977). Submarines of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-962-7.

- Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-146-5.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- Heden, Karl Eric (2006). Sunken Ships, World War II: U.S. Naval Chronology Including Submarine Losses of the United States, England, Germany, Japan, Italy. History Reference Center: Branden Books. ISBN 0828321183.

- McCartney, Innes (2006). British Submarines 1939–1945. New Vanguard. 129. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-007-9.