HMS Russell (1901)

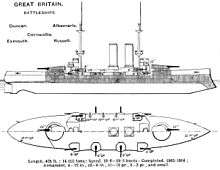

HMS Russell was a Duncan-class pre-dreadnought battleship of the Royal Navy commissioned in 1903. Built to counter a group of fast Russian battleships, Russell and her sister ships were capable of steaming at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph), making them the fastest battleships in the world. The Duncan-class battleships were armed with a main battery of four 12-inch (305 mm) guns and they were broadly similar to the London-class battleships, though of a slightly reduced displacement and thinner armour layout. As such, they reflected a development of the lighter second-class ships of the Canopus-class battleship. Russell was built between her keel laying in March 1899 and her completion in February 1903.

HMS Russell | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Russell |

| Namesake: | Edward Russell, 1st Earl of Orford |

| Builder: | Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company, Jarrow |

| Laid down: | 11 March 1899 |

| Launched: | 19 February 1901 |

| Completed: | February 1903 |

| Commissioned: | 19 February 1903 |

| Fate: | Sunk by mine, 27 April 1916 off Malta |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Duncan-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 432 ft (132 m) (loa) |

| Beam: | 75 ft 6 in (23.01 m) |

| Draught: | 25 ft 9 in (7.85 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Range: | 6,070 nmi (11,240 km; 6,990 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 720 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

Russell served with the Mediterranean Fleet until 1904, at which time she was transferred to the Home Fleet; in 1905 the Home Fleet became the Channel Fleet. She moved to the Atlantic Fleet in early 1907 before returning to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1909. In another fleet reorganisation in 1912, the Mediterranean Fleet became part of the Home Fleet and it was later transferred to British waters. Russell served as the flagship of the 6th Battle Squadron from late 1913 until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

After the start of the war, Russell was assigned to the Grand Fleet and worked with the fleet's cruisers on the Northern Patrol, and in November, she bombarded German-occupied Zeebrugge. In November 1915 she was sent to the Mediterranean to support the Dardanelles Campaign, though she did not see extensive use there. On 27 April 1916 she was sailing off Malta when she struck two mines laid by a German U-boat. Most of her crew survived the sinking, though 125 men were killed.

Design

The six ships of the Duncan class were ordered in response to the Russian Peresvet-class battleships that had been launched in 1898. The Russian ships were fast second-class battleships, so William Henry White, the British Director of Naval Construction, designed the Duncan class to match the purported top speed of the Russian vessels. To achieve the higher speed while keeping displacement from growing, White was forced to reduce the ships' armour protection significantly, effectively making the ships enlarged and improved versions of the Canopus-class battleships of 1896, rather than derivatives of the more powerful Majestic, Formidable, and London series of first-class battleships. The Duncans proved to be disappointments in service, owing to their reduced defensive characteristics, though they were still markedly superior to the Peresvets they had been built to counter.[1]

Russell was 432 feet (132 m) long overall, with a beam of 75 ft 6 in (23.01 m) and a draft of 25 ft 9 in (7.85 m). The Duncan-class battleships displaced 13,270 to 13,745 long tons (13,483 to 13,966 t) normally and up to 14,900 to 15,200 long tons (15,100 to 15,400 t) fully loaded. Her crew numbered 720 officers and ratings. The Duncan-class ships were powered by a pair of 4-cylinder triple-expansion engines that drove two screws, with steam provided by twenty-four Belleville boilers. The boilers were trunked into two funnels located amidships. The Duncan-class ships had a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) from 18,000 indicated horsepower (13,000 kW).[2] This made Russell and her sisters the fastest battleships in the world for several years. At a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), the ship could steam for 6,070 nautical miles (11,240 km; 6,990 mi).[3]

Russell had a main battery of four 12-inch (305 mm) 40-calibre guns mounted in twin-gun turrets fore and aft. The ships also mounted a secondary battery of twelve 6-inch (152 mm) 45-calibre guns mounted in casemates, in addition to ten 12-pounder 3 in (76 mm) guns and six 3-pounder 47 mm (1.9 in) guns for defence against torpedo boats. As was customary for battleships of the period, she was also equipped with four 18-inch (457 mm) torpedo tubes submerged in the hull.[2]

Russell had an armoured belt that was 7 in (178 mm) thick; the transverse bulkhead on the aft end of the belt was 7 to 11 in (178 to 279 mm) thick. Her main battery turrets' sides were 8 to 10 in (203 to 254 mm) thick, atop 11 in (279 mm) barbettes, and the casemate battery was protected with 6 in of Krupp steel. Her conning tower had 12-inch-thick sides. She was fitted with two armoured decks, 1 and 2 in (25 and 51 mm) thick, respectively.[2]

Operational history

Pre-World War I

Russell was named after Edward Russell, 1st Earl of Orford, a former Royal Navy officer and Commander-in-Chief of the Navy in the 17th century. She was laid down by Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company at Jarrow on 11 March 1899 and launched on 19 February 1902. She arrived at Sheerness later the same month and went to Chatham Dockyard for steam and gun-mounting trials. Construction of Russell was completed in February 1903.[2] During her sea trials, she was painted in the black and buff paint scheme used during the Victorian period, though after entering service she was repainted in the new grey paint scheme.[4]

Russell commissioned at Chatham Dockyard on 19 February 1903 for service in the Mediterranean Fleet, in which she served until April 1904. On 7 April 1904 she recommissioned for service in the Home Fleet. When the Home Fleet became the Channel Fleet in January 1905, she became a Channel Fleet unit. She transferred to the Atlantic Fleet in February 1907.[5] In July 1908, Russell visited Canada during the Quebec Tercentenary, in company with her sister ships Albemarle, Duncan, and Exmouth.[6] While there on 16 July she collided with the cruiser Venus off Quebec, but suffered only minor damage.[5]

In 1909, Russell had her armament overhauled, which included the installation of new traversing and elevation gear and sighting equipment. She also had identification bands painted onto her funnels. On 30 July 1909, Russell transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet. Under a fleet reorganisation of 1 May 1912, the Mediterranean Fleet became the 4th Battle Squadron, First Fleet, Home Fleet, and changed its base from Malta to Gibraltar;[7] Russell transferred to home waters in August 1912.[8] In September 1913, Russell was reduced to a nucleus crew in the commissioned reserve and assigned to the 6th Battle Squadron, Second Fleet. Beginning in December 1913, she served as Flagship, 6th Battle Squadron, and Flagship, Rear Admiral, Home Fleet, at the Nore. During this period, the ship had her anti-torpedo nets removed.[9]

On 7–8 July 1914, Russell ferried representatives of the British government, led by Lord Beauchamp, from Dover to Guernsey to attend the unveiling of a monument to Victor Hugo. French government representatives were carried by the French cruiser Dupetit-Thouars.[10]

World War I

North Sea and the Channel

When World War I began in August 1914, plans originally called for Russell and battleships Agamemnon, Albemarle, Cornwallis, Duncan, Exmouth, and Vengeance to combine in the 6th Battle Squadron and serve in the Channel Fleet, where the squadron was to patrol the English Channel and cover the movement of the British Expeditionary Force to France. However, plans also existed for the 6th Battle Squadron to be assigned to the Grand Fleet. When the war began, the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, requested that Russell and her four surviving sister ships of the Duncan class (Albemarle, Cornwallis, Duncan, and Exmouth) be assigned to the 3rd Battle Squadron in the Grand Fleet for patrol duties to make up for the Grand Fleet's shortage of cruisers. Accordingly, the 6th Battle Squadron was abolished temporarily. Russell, Exmouth, and Albemarle were the only ships in a condition to immediately join Jellicoe, so they left without the rest of the squadron on 5 August. They arrived in Scapa Flow on the night of 7–8 August. The ships worked with Grand Fleet cruisers on the Northern Patrol.[5][11][12]

Russell and her four Duncan-class sisters, as well as the battleships of the King Edward VII class, were temporarily transferred to the Channel Fleet on 2 November 1914 as reinforcements in the face of German Navy activity in the Channel Fleet's area.[5] The following day, the German fleet raided Yarmouth; at the time, Russell and the rest of the 3rd Squadron were dispersed on the Northern Patrol, and were thus unavailable during the German attack.[13] On 13 November 1914 the King Edward VII-class ships returned to the Grand Fleet, but Russell and the other Duncans stayed in the Channel Fleet, where they reconstituted the 6th Battle Squadron on 14 November 1914, with Russell serving as the squadron's flagship. The squadron was based at Portland, although it transferred immediately, 14 November, to Dover. However, due a lack of antisubmarine defences at Dover, particularly after the harbour's anti-submarine boom was swept away in a gale, it returned to Portland on 19 November 1914.[5][14]

The 6th Battle Squadron was given a mission of bombarding German submarine bases on the coast of Belgium, and Russell participated in the bombardment of German submarine facilities at Zeebrugge on 23 November 1914 in company with Exmouth. The two ships left Portland on 21 November accompanied by eight destroyers, a group of trawlers, and a pair of airships to observe the fall of shot, though the airships failed to arrive in time for the operation. Russell and Exmouth closed to 6,000 yards (5,500 m) of the port and shelled the harbour, the railroad station, and coastal defences. The two ships fired some 400 shells in total and observed several fires ashore; reports from Dutch observers indicated significant damage had been inflicted,[15] but the attack achieved very little and discouraged the Royal Navy from continuing such bombardments.[16]

The 6th Battle Squadron returned to Dover in December 1914, then transferred to Sheerness on 30 December to relieve the 5th Battle Squadron there in guarding against a German invasion of the United Kingdom. Between January and May 1915, the 6th Battle Squadron was dispersed. Russell and Albemarle remained with the Grand Fleet through April; on 19 April, they were detached from the fleet base at Rosyth to conduct training exercises in Scapa Flow. They rejoined the fleet for a sortie on 21 April Russell left the squadron in April 1915 and rejoined the 3rd Battle Squadron in the Grand Fleet at Rosyth. She underwent a refit at Belfast in October–November 1915. During this refit she received a pair of 3-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft guns on her quarterdeck.[17][18]

Mediterranean

On 6 November 1915, a division of the 3rd Battle Squadron consisting of battleships Hibernia (the flagship), Zealandia, Albemarle, and Russell was detached from the Grand Fleet to reinforce the British Dardanelles Squadron in the Gallipoli Campaign at the Gallipoli Peninsula. Russell was at that time in Belfast, and she joined the other ships while they were en route. Albemarle had to turn back almost immediately due to heavy weather damage, but the other ships continued to the Mediterranean, where Russell took up her duties at the Dardanelles in December 1915, based at Mudros with Hibernia and held back in support. Her only action in the campaign was her participation in the evacuation of Cape Helles from 7 January to 9 January 1916, and she was the last battleship of the British Dardanelles Squadron to leave the area. She relieved Hibernia as Divisional Flagship, Rear Admiral, in January 1916.[8][19][20]

After the conclusion of the Dardanelles campaign, Russell stayed on in the eastern Mediterranean. Russell was steaming off Malta early on the morning of 27 April 1916 when she struck two naval mines that had been laid by the German submarine U-73. A fire broke out in the after part of the ship and the order to abandon ship was passed; after an explosion near the after 12-inch (305 mm) turret, she took on a dangerous list. However, she sank slowly, allowing most of her crew to escape. A total of 27 officers and 98 ratings were lost.[19][Note 1] John H. D. Cunningham served aboard her at the time as a lieutenant commander and survived her sinking; he would one day become First Sea Lord.[21]

According to the naval historian R. A. Burt, insufficient internal subdivision, which limited the ability of the crew to counter-flood to offset underwater damage, contributed significantly to the loss of Russell and her sister Cornwallis, both of which listed badly before sinking.[22]

The wreck was examined for the first time in 2003 by a British dive team; the ship lies at a depth of 63 fathoms (115 m) about 3.2 nautical miles (6 km) from the Delimara Peninsula. Her stern was blown off by the mine.[23]

Footnotes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Russell (ship, 1901). |

Notes

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 9, puts the loss of life at 126 rather than 125

Citations

- Burt, pp. 227–229.

- Gardiner, p. 37.

- Burt, pp. 229, 232.

- Burt, p. 237.

- Burt, p. 245.

- "The Tercentenary Celebrations", p. 445.

- Burt, pp. 241, 245.

- Gardiner & Gray, p. 9.

- Burt, pp. 241–242, 245.

- "Naval Matters—Past and Prospective: Sheerness Dockyard". The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect. Vol. 37 no. 443. August 1914. p. 7.

- Corbett 1920, pp. 39–40, 75, 214, 254.

- Jellicoe, p. 93.

- Corbett 1920, p. 259.

- Corbett 1921, pp. 9–10, 19.

- Corbett 1921, pp. 12–13.

- Goldrick, p. 182.

- Burt, pp. 242, 245.

- Jellicoe, pp. 212–213.

- Burt, p. 246.

- Corbett 1923, pp. 248–252, 260.

- "Cunningham, Sir John Henry Dacres". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Burt, p. 236.

- Cini, David (18 July 2003). "Deep sea dive recalls WWI sailor's incredible escape". Times of Malta. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

References

- Burt, R. A. (2013) [1988]. British Battleships 1889–1904. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-173-1.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1920). Naval Operations: To The Battle of the Falklands, December 1914. I. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 174823980.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1921). Naval Operations: From The Battle of the Falklands to the Entry of Italy Into the War in May 1915. II. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 924170059.

- Corbett, Julian Stafford (1923). Naval Operations: The Dardanelles Campaign. III. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 174824081.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Goldrick, James (1984). The King's Ships Were at Sea: The War in the North Sea, August 1914 – February 1915. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-334-2.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 162593478.

- "The Tercentenary Celebrations". The Canada Gazette. London: Charles Hunt: 445. 1908. OCLC 47522100.

Further reading

- Dittmar, F. J.; Colledge, J. J. (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0380-4.

- Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers: A Technical Directory of All the World's Capital Ships From 1860 to the Present Day. London: Salamander Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86101-142-1.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1957]. British Battleships. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-075-5.

- Pears, Randolph (1979). British Battleships 1892–1957: The Great Days of the Fleets. London: G. Cave Associates. ISBN 978-0-906223-14-7.