HMS Erin

HMS Erin was a dreadnought battleship of the Royal Navy, originally ordered by the Ottoman government from the British Vickers Company. The ship was to have been named Reşadiye when she entered service with the Ottoman Navy. The Reşadiye class was designed to be at least the equal of any other ship afloat or under construction.[1] When the First World War began in August 1914, Reşadiye was nearly complete and was seized at the orders of Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty to keep her in British hands and prevent her from being used by Germany or German allies. There is no evidence that the seizure played any part in the Ottoman government declaring war on Britain and the Entente Cordiale.

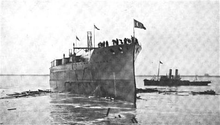

Erin in the Moray Firth, August 1915 | |

| Name: | Reşad V |

| Namesake: | Sultan Mehmed V |

| Ordered: | 8 June 1911 |

| Builder: | Vickers |

| Cost: | £2,500,000 (est.) |

| Yard number: | 425 |

| Laid down: | 6 December 1911 |

| Launched: | 3 September 1913 |

| Renamed: | Reşadiye |

| Fate: | Seized, 31 July 1914 |

| Name: | Erin |

| Namesake: | Erin |

| Completed: | August 1914 |

| Decommissioned: | May 1922 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrap, 19 December 1922 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type: | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 559 ft 6 in (170.54 m) (o/a) |

| Beam: | 91 ft 7 in (27.9 m) |

| Draught: | 28 ft 5 in (8.7 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range: | 5,300 nmi (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: | |

| Service record | |

| Part of: |

|

| Operations: | |

Aside from a minor role in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the inconclusive Action of 19 August the same year, Erin's service during the war generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war; she was reduced to reserve and used as a training ship. Erin served as the flagship of the reserve fleet at the Nore for most of 1920. She was sold for scrap in 1922 and broken up the following year.

Design and description

The design was based on the King George V class, but employed the six-inch (152 mm) secondary armament of the Iron Duke class.[2] Erin had an overall length of 559 feet 6 inches (170.54 m), a beam of 91 feet 7 inches (27.9 m) and a draught of 28 feet 5 inches (8.7 m). She displaced 22,780 long tons (23,150 t) at normal load and 25,250 long tons (25,660 t) at deep load. In 1914 her crew numbered 976 officers and ratings and 1,064 a year later.[3]

Erin was powered by a pair of Parsons direct-drive steam turbine sets, each driving two shafts, using steam from 15 Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines, rated at 26,500 shaft horsepower (19,800 kW), were intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). The ship carried enough coal and fuel oil for a maximum range of 5,300 nautical miles (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3] This radius of action was somewhat less than that of contemporary British battleships, but was adequate for operations in the North Sea.[2]

Armament and armour

The ship was armed with a main battery of ten BL 13.5 in (343 mm) MK VI guns mounted in five twin-gun turrets, designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X' and 'Y' from front to rear.[Note 1] They were arranged in two superfiring pairs, one forward and one aft of the superstructure; the fifth turret was amidships, between the funnels and the rear superstructure. Close-range defence against torpedo boats was provided by a secondary battery of sixteen BL 6-inch Mk XVI guns. The ship was also fitted with six quick-firing (QF) 6-pounder (57 mm) Hotchkiss guns. As was typical for capital ships of the period, she was equipped with four submerged 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes on the broadside. Erin was protected by a waterline armoured belt that was 12 inches (305 mm) thick over the ship's vitals. Her decks ranged in thickness from 1 to 3 inches (25 to 76 mm). The main gun turrets were 11 inches (279 mm) thick and were supported by barbettes 9–10 inches (229–254 mm) thick.[6]

Wartime modifications

Four of the six-pounder guns were removed in 1915–1916 and a QF three-inch 20-cwt[Note 2] anti-aircraft (AA) gun was installed on the former searchlight platform on the aft superstructure.[7] A fire-control director was installed on the tripod mast between May and December 1916.[8] A pair of directors for the secondary armament were fitted to the legs of the tripod mast in 1916–1917 and another three-inch AA gun was added on the aft superstructure. In 1918, a high-angle rangefinder was fitted and flying-off platforms were installed on the roofs of 'B' and 'Q' turrets.[9]

Construction and career

Erin originally was ordered by the Ottoman Empire on 8 June 1911,[10] at an estimated cost of £2,500,000, with the name of Reşad V[2][11][12] in honour of Mehmed V Reşâd, the ruling Ottoman Sultan,[13] but was renamed Reşadiye during construction.[Note 3] She was laid down at the Vickers shipyard in Barrow-in-Furness on 6 December 1911 with yard number 425, but construction was suspended in late 1912 during the Balkan Wars and resumed in May 1913.[10] The ship was launched on 3 September and completed in August 1914.[11] After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, the British postponed delivery of Reşadiye on 21 July, despite the completion of payments and the arrival of the Ottoman delegation to collect Reşadiye and another dreadnought battleship, Sultan Osman I, after their sea trials.[14] The First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill ordered the Royal Navy to detain the ships on 29 July and prevent Ottoman naval personnel from boarding them; two days later, British sailors formally seized them and Reşadiye was renamed Erin, a poetical name for Ireland. He did this on his own initiative to augment the Royal Navy's margin of superiority over the German High Seas Fleet and to prevent them from being acquired by Germany or its allies.[15][16]

The takeover caused considerable ill will in the Ottoman Empire, where public subscriptions had partially funded the ships. When the Ottoman government had been in a financial deadlock over the budget of the battleships, donations for the Ottoman Navy had come in from taverns, cafés, schools and markets, and large donations were rewarded with a "Navy Donation Medal". The seizure, and the gift of the German battlecruiser Goeben to the Ottomans, influenced public opinion in the Empire to turn away from Britain.[17] Historian David Fromkin has speculated that the Turks promised to transfer Sultan Osman I to the Germans in exchange for signing a secret defensive alliance on 1 August. Despite the alliance, the Ottoman government was intent on remaining neutral until Russian disasters during the invasion of East Prussia in September persuaded Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha, the Ministers of War and of the Marine, respectively, that the time was ripe to exploit Russian weakness. Unbeknownst to any of the other members of the government, Enver and Djemal authorized Vice Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, the German commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy, to attack Russian ships in the Black Sea in late October under the pretext of defending its warships from Russian attacks. Souchon, frustrated with Ottoman neutrality, took matters into his own hands and bombarded Russian ports in the Black Sea on 29 October as unambiguous evidence of an Ottoman attack and forced the government's hand into joining the war on Germany's side.[18]

1914–1915

Captain Victor Stanley was appointed as Erin's captain.[19] On 5 September, she joined the Grand Fleet, commanded by Admiral John Jellicoe, at Scapa Flow in Orkney and was assigned to the Fourth Battle Squadron (BS).[11] Erin sailed with the ships of the Grand Fleet as they departed from Loch Ewe in Scotland on 17 September, for gunnery practice west of the Orkney Islands the following day. After the exercise, they began a fruitless search for German ships in the North Sea that was hampered by bad weather. The Grand Fleet arrived at Scapa Flow on 24 September to refuel before departing the next day for more target practice west of Orkney.[20][Note 4] In early October the Grand Fleet sortied into the North Sea to provide distant cover for a large convoy transporting Canadian troops from Halifax, Nova Scotia and returned to Scapa on 12 October. Reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and on 16 October, he ordered that the bulk of the Grand Fleet be dispersed to Lough Swilly, Ireland. Jellicoe took the Grand Fleet to sea on 3 November for gunnery training and battle exercises and the 4th BS returned to Scapa six days later. On the evening of 22 November, the Grand Fleet conducted another abortive sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Erin stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back at Scapa Flow by 27 November. On 16 December, the Grand Fleet sortied during the German raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby but failed to intercept the High Seas Fleet. Erin and the rest of the Grand Fleet made another sweep of the North Sea on 25–27 December.[22]

Jellicoe's ships, including Erin, practised gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of the Orkney and Shetland Islands.[23] On the evening of 23 January, the bulk of the Grand Fleet sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers but the fleet was too far away to participate in the Battle of Dogger Bank the following day.[24] On 7–10 March, the fleet made a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres. Another cruise took place on 16–19 March. On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off Shetland on 20–21 April.[25]

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet practised gunnery and battle exercises west of Shetland and more training off Shetland from 11 July.[26] On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted training exercises and then made another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Erin participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[27] The ship was transferred to the Second Battle Squadron sometime between September and December.[28][29]

1916–1918

The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea and the operation was confined to the northern end. Another sweep began on 6 March but was abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the destroyer escorts. On the night of 25 March, Erin and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base.[30] On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Russian Navy re-laid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea. The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before sailing south, over intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft. The Germans had withdrawn before the fleet arrived. On 2–4 May, the Grand Fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention on the North Sea.[31]

Battle of Jutland

To lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet (Admiral Reinhard Scheer) composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers. Room 40 at the Admiralty had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. The Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, with 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before, to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[32]

During the Battle of Jutland on 31 May, Beatty's battlecruisers managed to bait Scheer and Hipper into a pursuit as they fell back upon the main body of the Grand Fleet. After Jellicoe deployed his ships into line of battle, Erin was the fourth from the head of the line.[33] Scheer's manoeuvres after spotting the Grand Fleet were generally away from Jellicoe's leading ships and the poor visibility hindered their ability to close with the Germans before Scheer could disengage under the cover of darkness. Opportunities to shoot during the battle were rare, and she only fired 6 six-inch shells from her secondary armament. Erin was the only British battleship not to fire her main guns.[34]

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea but miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or that it could be forced into an engagement at a disadvantage.[35] When Stanley was promoted to rear-admiral on 26 April 1917, he was replaced by Captain Walter Ellerton.[36][37]

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet sortied against British convoys to Norway. Wireless silence was enforced, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser SMS Moltke forced her to break radio silence and inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany.[38] The ship was at Rosyth, Scotland, when the surrendered High Seas Fleet arrived on 21 November and she remained part of the 2nd BS through 1 March 1919.[39][40]

Postwar

Captain Herbert Richmond assumed command on 1 January 1919.[41] By 1 May, Erin had been assigned to the 3rd Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet.[42] In October, she was placed in reserve at the Nore but was stationed at Portland Harbour as of 18 November.[11][43] Richmond was relieved by Captain Percival Hall-Thompson on 1 December. Erin had returned to the Nore by January 1920 and became a gunnery training ship there by February.[44][45] By June, the ship had become flagship of Rear-Admiral Vivian Bernard, Rear-Admiral, Reserve Fleet, Nore.[46] In July and August 1920, she underwent a refit at Devonport Dockyard.[11] Through 18 December 1920, Erin remained Bernard's flagship and continued to serve as a gunnery training ship.[47] The Royal Navy had originally intended that she should be retained as a training ship under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, but a change of plan meant that this role was filled by Thunderer, so the ship was listed for disposal in May 1922. Erin was sold to the ship-breaking firm of Cox and Danks on 19 December and broken up at Queenborough the following year.[11]

Notes

- Sources disagree on the number of each model of gun mounted on the ship, although everyone agrees that most of the guns fitted were Mk VI guns. Friedman claims that two Mk V guns were mounted and that doing so expedited the completion of the ship. Campbell says that she carried a Mk V gun for a time. Campbell and Friedman state the Mk V guns aboard Erin were provided with reduced powder charges to match the ballistic trajectories of the Mk VI guns.[4] Preston says that they were all Mk VI guns while Parkes and Silverstone do not identify the exact types.[2][5]

- "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

- Sources disagree regarding the initial name of the ship. Langensiepen and Güleryüz, in their history of the Ottoman Navy, state that her only name prior to the British seizure was Reşadiye and Silverstone agrees with them.[13][10]

- In his 1919 book, Jellicoe generally named ships only when they were undertaking individual actions. Usually he referred to the Grand Fleet or by squadrons. Unless otherwise specified, this article assumes that Erin is participating in the activities of the Grand Fleet.[21]

Citations

- Burt, p. 245

- Preston, p. 36

- Burt, p. 248

- Friedman, p. 52; Campbell 1981, p. 97

- Parkes, p. 597; Silverstone, pp. 192, 405

- Burt, pp. 247–248, 252

- Burt, pp. 252–253

- Brooks, p. 168

- Burt, pp. 253, 256

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 141

- Burt, p. 256

- Parkes, p. 599

- Silverstone, p. 409

- Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 29

- Silverstone, p. 230

- Fromkin, pp. 56–57

- Hough, pp. 143–144

- Fromkin, pp. 58–61, 67–72

- "The Navy List". Internet Archive. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1914. p. 312. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Jellicoe, pp. 129–133

- Jellicoe, p. 129

- Jellicoe, pp. 135–137, 143, 156, 158, 163–165, 179, 182–184

- Jellicoe, p. 190

- Monograph No. 12, p. 224

- Jellicoe, pp. 194–196, 206, 211–212

- Jellicoe, pp. 217–219, 221–222

- Jellicoe, pp. 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. September 1915. p. 10. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. December 1915. p. 10. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280

- Jellicoe, pp. 284, 286–290

- Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- Corbett, frontispiece map and p. 428

- Campbell 1986, pp. 96, 148, 197–198, 248, 273–274, 346, 358

- Halpern, pp. 330–332

- "Victor Albert Stanley". The Dreadnought Project. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1918. p. 788. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Halpern, pp. 418–420

- "Operation ZZ". The Dreadnought Project. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 1 March 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 770. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 May 1919. p. 5. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 709. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. January 1920. pp. 707, 770. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 770. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. October 1920. p. 695–6. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 December 1920. pp. 695–6, 770–1. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

References

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 978-0-85177-685-9.

- Burt, R. A. (2012). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-053-5.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1981). "British Naval Guns 1880–1945, Number Two". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship V. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-85177-244-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-324-3.

- Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. III (reprint of the 1940 second ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 978-1-870423-50-2.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7

- Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-0857-9.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Hough, Richard (1967). The Great Dreadnought: The Strange Story of H.M.S. Agincourt: The Mightiest Battleship of World War I. New York: Harper & Row. OCLC 914101.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank–24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). III. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1921. pp. 209–226. OCLC 220734221 – via Royal Australian Navy.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships 1860–1950. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-075-5.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-88254-979-8.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916 (repr. ed.). London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-917-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Erin. |