HKP 562 forced labor camp

HKP 562 was the site of a Nazi forced labor camp for Jews in Vilnius, Lithuania, during the Holocaust. Located at 47 & 49 Subačiaus Street, in apartment buildings originally built to house poor members of the Jewish community, the camp was used by the German army as a slave labor camp from September 1943 until July 1944. During that interval, the camp was officially owned and administered by the SS, but run on a day-to-day basis by a Wehrmacht engineering unit, Heereskraftfahrpark (HKP) 562 (Army Motor Vehicle Repair Park 562), stationed in Vilnius. HKP 562's commanding officer, Major Karl Plagge, was sympathetic to the plight of his Jewish workers. Plagge and some of his men made efforts to protect the Jews of the camp from the murderous intent of the SS. It was partially due to the covert resistance to the Nazi policy of genocide toward the Jews by members of the HKP 562 engineering unit that over 250 Jewish men, women and children survived the final liquidation of the camp in July 1944, the single largest group of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in Vilnius.

| HKP 562 forced labor camp | |

|---|---|

| Nazi concentration camp | |

A Holocaust memorial near the former camp, Subačiaus Street | |

Location of HKP 562 forced labor camp within Lithuania | |

| Coordinates | 54°40′34″N 25°18′18″E |

| Known for | largest single group of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in Vilnius |

| Location | Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Operated by | SS and Heereskraftfahrpark (HKP) 562 (Army Motor Vehicle Repair Park 562), |

| Commandant | Major Karl Plagge |

| Original use | apartment buildings |

| Operational | 16 September 1943 – 3 July 1944 |

| Inmates | Jews |

| Number of inmates | 1,234 |

| Killed | 750 |

| Liberated by | red Army, July 1944 |

| Notable inmates | Hirsch Schwartzberg, Samuel Bak |

Establishment

After having hired endangered Jews in the Vilna Ghetto to work in his unit's workshops from 1941-1943, thereby protecting the workers and their families from the murderous Aktions of the SS, the HKP camp was hastily erected in September 1943 when Plagge learned of the impending liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto, where all inhabitants were to be killed regardless of their work papers. Plagge first traveled to Kaunas to the Wehrmacht headquarters and then to Riga to the SS administrative offices to argue on behalf of establishing a free standing camp outside of the Vilna Ghetto. He met considerable resistance, especially from the SS, regarding this plan and his insistence that the women and children not be separated from the men, which he said would negatively affect worker morale and productivity. He was ultimately successful and on the evening of September 16, 1943 drove a convoy of trucks into the Vilna Ghetto and loaded more than 1200 endangered Jewish ghetto residents onto his trucks and transported them to the relative safety of the newly erected HKP camp on Subocz (Subacious) street.[1] One week later the Vilna Ghetto was liquidated by the SS and its 15,000 remaining residents were either killed in the nearby killing grounds at Ponary or transported to concentration camps across Nazi occupied Europe. Documents found by the Jewish Museum in Vilnius show that the camp housed 1234 Jewish men, women and children.[2] Initially, only men were employed in vehicle repair workshops in and around the camp; however, later after an attempt was made by the SS to transfer the women and children to the Kaunas concentration camp in January 1944, Major Plagge engaged two clothing manufacturers to set up clothing repair shops in the top two floors of one of the Apartment buildings and put the women and older children to work so that they would not appear to be idle to outside observers.[3] Plagge also gave orders that "the civilians are to be treated with respect" and thus the camp was largely free of the abuse and brutality found in most slave labor camps in Nazi-occupied Poland.[4] In spite of the generally benign attitude of the officers and men of the HKP unit, the SS did enter the camp on several occasions and committed atrocities. Most notable was the Kinderaktion (an action against the camp's children) on 27 March 1944, during which the SS, supervised by Martin Weiss, removed the vast majority of the 250 children living in the camp, who were then taken to their deaths.

Liquidation

As the Red Army approached Vilnius in late June 1944, the Wehrmacht prepared to retreat. The Jewish prisoners in the camp were aware (having heard news reports from the BBC on covert radio sets) that whenever the Red Army liberated a Jewish slave-labor camp, they found all the inmates dead, having been shot by SS killing squads just before the Germans retreated. Thus many of the prisoners had been working on hiding places (called Malines) or escape plans in the months leading up to the summer of 1944. But they needed to know when the SS squads would arrive to exterminate the prisoners. On Saturday 1 July 1944, Major Plagge entered the camp, with SS Oberscharfürhrer Richter at his side and made an informal speech as the camps Jewish prisoners gathered around him. Plagge announced that he and his men had been ordered to withdraw to the west, and that he had not been able to obtain permission to take the workers with the unit; however he reassured them that the prisoners were to be relocated by the SS on Monday July 3 and commented that they should not worry because they all knew that the SS was an organization devoted to the protection of refugees.[5] With this covert warning, over half the camp's prisoners went into hiding before the SS death squads arrived on 3 July 1944. The 500 prisoners who did appear at the roll call called by the SS were taken to the forest of Paneriai and shot. Over the next three days the SS searched the camp and its surroundings and succeeded in finding half of the missing prisoners; these 250 Jews were shot in the camp courtyard and behind Building 2. However, when the Red Army captured Vilnius a few days later, some 250 of the camp's Jews emerged from their hiding places and were the largest single group of Jewish survivors of the Holocaust in Vilnius.

Recent Research

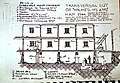

In July and August 2017 a research team led by Richard Freund from the University of Hartford conducted archeological surveys of the former HKP camp site using non-invasive techniques such as Ground Penetrating Radar, Electric Resistance Tomography and drone obtained high resolution topographical maps. Their studies strongly supported the testimony which placed the location of a large mass grave from the final liquidation of the camp at the south end of the courtyard (under the current memorials as well as the parking area). They also confirmed the location of a trench near the outside wall of building number two (the western building) where witnesses reported that prisoners were shot and buried in a long trench along the side of the building. Additionally using drawings and written accounts of camp survivors the team was able to locate the "large maline" where 100 men, women and children succeeding in hiding during the final days of the camp and thus evaded the SS killing squads that descended on the camp on July 3–5, 1944.

Sketch made by former HKP inmate Gary Gerstein, who was an 8 year old child in July 1944. He later became an architect and drew this schematic of his hiding place with the help of his older cousin Pearl Good who also survived in this maline

Sketch made by former HKP inmate Gary Gerstein, who was an 8 year old child in July 1944. He later became an architect and drew this schematic of his hiding place with the help of his older cousin Pearl Good who also survived in this maline- A memorial marking the burial site of Jews murdered at the former camp

Interior of large maline found in 2017, corresponds to area 5 on Gary Gerstein's schematic of the maline

Interior of large maline found in 2017, corresponds to area 5 on Gary Gerstein's schematic of the maline.jpg) Drone obtained image of the former HKP Slave Labor Camp at 47-49 Subaciaus Street Vilnius

Drone obtained image of the former HKP Slave Labor Camp at 47-49 Subaciaus Street Vilnius

Notable people

- Major Karl Plagge

Former Prisoners at HKP 562:

- Hirsch Schwartzberg, Jewish leader of Holocaust survivors (Yiddish: בפרייטה יידין אויף ברלין) under the American occupation of Berlin

- Samuel Bak

- Samuel Esterowicz

References

- Good, Michael (2005). The Search For Major Plagge: The Nazi Who Saved Jews. Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2440-6.

- Guzenberg, Irina (2002). Žydų darbo stovykla HKP: 1943–1944: dokumentai. The Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum. ISBN 9955-9556-1-9.

- http://www.searchformajorplagge.com/searchformajorplagge.com/Plagge_Documents.html

- Good, Michael (2005). The Search For Major Plagge: The Nazi Who Saved Jews. Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2440-6.

- Wette, Wolfram (2005). Viefhaus, Marianne (ed.). Zivilcourage in der Zeit des Holocaust. Karl Plagge aus Darmstadt, ein "Gerechter unter den Völkern". Darmstadt: Darmstädter Geschichtswerkstatt e.V. and the Magistrat der Wissenschaftsstadt Darmstadt. p. 111.

- Good, Michael (2005). The Search For Major Plagge: The Nazi Who Saved Jews. Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2440-6.

- Guzenberg, Irina (2002). Žydų darbo stovykla HKP: 1943–1944: dokumentai. The Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum. ISBN 9955-9556-1-9.