HIV/AIDS activism

Social activism against the spread of HIV/AIDS and in support of effective treatment has taken place in multiple nations across the world over the past several decades. In terms of the complex history of HIV/AIDS in human beings, widespread criticism by regular individuals against public health organizations (including, often, government-managed medical bureaucracies) have escalated into protest movements due to slow treatment responses (and, sometimes, outright discrimination against patients plus the proliferation of misconceptions about HIV/AIDS). Methods of demonstration have included the hanging of political leaders in effigy, pamphleteer activities, placard waving, public marches, sit-ins, and the like.

.jpg)

Methods and organizational structures

.jpg)

HIV/AIDS activism has often drawn its numbers from socially active patients who struggle with their health themselves as well as the friends and family of those diagnosed. Historically, these networks have swollen in size and thus influence by taking in sympathetic outsides existing within the same broader social community. For example, the South African fight against HIV/AIDS began largely among patients only to grow to a concern among most of the nation's gay men and then to a broader coalition of South Africans fighting for anti-disease treatment as a part of a socio-economic right to healthcare.[1]

Methods of protest have included the hanging of political leaders in effigy, pamphleteer activities, Placard waving, public marches, sit-ins, and many other such activities. Sometimes, sit-ins will escalate to demonstrations known as die-ins, during which protests will lie in various motionless poses to simulate being dead.

In the U.S., the iconography of the pink triangle (originally utilized by Nazi Germany during its persecution of LGBT people) and the slogan 'Silence=Death' together is common. Activists placed versions of the image across New York City during the worst times of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s. It's since been printed on t-shirts and in other types of media.[2]

History of anti-disease activism by region

History of anti-disease activism in Africa

The widespread belief in various misconceptions about HIV/AIDS has resulted in a serious handicap holding back treatment in certain parts of Africa. Activists have worked in a variety of different nations to promote effective treatment and to fight back against the myth. One particular example that's drawn international media attention is the 'virgin cleansing myth', with some communities in Africa believing that sex with a un-experienced partner can cure either AIDS or the underlying HIV infection itself. Activist Betty Makoni is one particular individual who has repeatedly worked to dispel the myth; in 1999, she founded the charity Girl Child Network to support Zimbabwe's young sex abuse victims.

In terms of social activism against governments, the controversial 2014 Anti-Homosexuality Bill of Uganda, which aimed at making homosexual sex a criminal offense, earned condemnation from individual activists as well as from groups such as The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Said organization stated that excluding marginalised groups would compromise efforts to stop the spread of AIDS in Uganda, a social problem to the point that a full 5.4% of the adult population had been infected with HIV by the year 2007.[3][4]

Struggles against HIV/AIDS have been a persistent problem in South Africa specifically, with over five million of the nation's people being HIV positive as of 2004 data. In the shadow of the collapsed apartheid system, the country-wide debate on the disease has focused on the intense conflict between social activists aligned with the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and the nation's government. Official support for AIDS denialism and the administering of what has been seen as inadequate access to HIV treatment outraged activists who viewed the government's policies as a denial of their basic right to life. Efforts by the TAC and associated individuals proved success when, in September 2003, the South African Cabinet finally instructed the country's health ministry to create a comprehensive HIV treatment and prevention plan. Later commentators have considered the TAC campaign as one of the most successful if not the most successful example of civil society pushing for human rights in South Africa since the end of apartheid.[1]

HIV prevalence varies drastically from country to country inside Africa. For example, UNAIDS research in 2007 found that 23.9% of adults in Botswana had been inflected in comparison to the values of 12.5% in Mozambique and 2.8% in Rwanda. The South Africa and Zimbabwe had values of 18.1% and 15.3%, respectively.[4]

History of anti-disease activism in North America

While the initial timeline of when and how HIV/AIDS crossed over into being a human infection is unclear, the timeline of early HIV/AIDS cases being under scientific dispute, the disease's spread in the United States began to reach a critical mass in the late 1970s and early 1980s period.

Because of the long incubation period of HIV, which can go on for over a decade while symptoms of AIDS gradually appear, HIV was not noticed at first by health professionals. The initially low incidence made detection even more tricky. By the time the first reported cases of AIDS were found in large U.S. cities such as New York City, the prevalence of HIV infection had passed 5% in some communities.[5]

The AIDS epidemic officially began on 5 June 1981, when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued findings in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report newsletter of unusual clusters of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) caused by a form of pneumocystis carinii (now recognized as a distinct species titled pneumocystis jirovecii). The report looked specifically at five homosexual men in the Los Angeles area.[6] Publications such as the San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times gave the CDC's findings news coverage.[7] June 1981 additionally saw the first AIDS patient getting received into care under the aegis of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). By August 1981, the CDC reported a full 108 cases of the new disease across America.[8]

By 1982, Representative Henry Waxman of California held the first congressional hearing exploring HIV/AIDS. The CDC estimated that tens of thousands would likely get affected by the disease.[9] A change in terminology meant the proliferation of the new, CDC-coined name of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS).[7]

That same year, a group of New Yorkers (Nathan Fain, Larry Kramer, Larry Mass, Paul Popham, Paul Rapoport, and Edmund White) officially established the Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC). An answering machine in the home of GMHC volunteer Rodger McFarlane, who later served as GMHC's first paid director, became the world's first AIDS hotline. It notably received over one hundred calls the first night. Besides functioning as a hub for social activism, GMHC established what are known as 'buddy programs' to provide people with AIDS with help during day-to-day events.[7]

In 1982 as well, activists Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz published How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach. In this short work, they described ways gay men could be sexual and affectionate while dramatically reducing the risk of contracting or spreading HIV. Both authors, gay men living with AIDS, set out the booklet as one of the first times men were advised to use condoms when having sexual relations with other men.[10]

In 1983, the GMHC sponsored a benefit performance of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, which served as the first major fund-raising event for AIDS. That same year, the official AIDS Candlelight Memorial was held for the first time. In terms of direct social activism, the organization Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund filed the world's first AIDS discrimination suit, receiving assistance from the GMHC.[7]

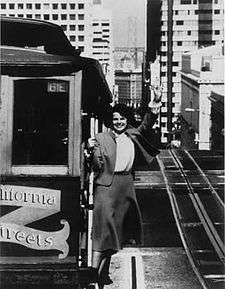

In 1984, Dianne Feinstein, then mayor of San Francisco, declared the first "AIDS Awareness Week" event. Featuring the primary goal of educating staff and students from San Francisco Community College District, it involved informing people about causes, effects, and symptoms of AIDS as well as prevention methods.[11][12] 1984 additionally saw the very first laboratory isolation of HIV, the breakthrough coming the separate research efforts of Dr. Luc Montagnier in France and Dr. Robert Gallo in the U.S.[7]

By 1985, publications such as Annals of Internal Medicine warned that "even if all transmission of the virus were to stop immediately, the... syndrome would continue to be a major public health problem for the foreseeable future."[5] That year additionally saw the rise to prominence of HIV/AIDS activist Ryan White, an Indiana teenager with AIDS who got barred from his school due to his status, and his life's work of speaking out publicly against AIDS stigma and discrimination. White eventually succumbed to the disease in 1990, dying at the age of eighteen.[7]

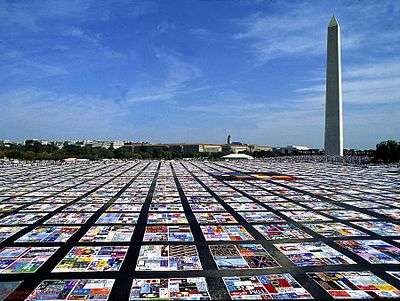

One of the most prominent forms of HIV/AIDS activism has been the creation of and public showings of the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Conceived in 1985 by activist Cleve Jones during a candlelight march held in remembrance of the 1978 assassinations of San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone, the idea came about after Jones requested people write the names of loved ones who died due to AIDS-related causes on signs. Those got taped to the old San Francisco Federal Building. The scene at the side of the building looked like an enormous patchwork quilt to Jones, and he felt inspired to try and make the concept into a reality. The quilt represented an inflection point within Jones' own life, the openly gay man have suffered from internalized homophobia and thoughts of suicide in his earlier years. The first public display of the project was at San Francisco City Hall in 1987.[13][11]

One of the most prominent HIV/AIDS activist groups, ACT UP, got its start in 1987 at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in New York State. Larry Kramer talked as part of a rotating series of speakers, and his well-attended speech focused on action to fight AIDS while condemning the Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC) group. Though a founder of GMHC, Kramer resigned due to his perceiving of the organization as politically impotent. During the 1980s and 1990s as well as onward, ACT UP focused on strident public demonstration aimed at shocking mainstream public opinion.

For example, the group's 11 October 1988 protest picked up national media coverage as it successfully shut down the headquarters of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a day. "Hey, hey, FDA, how many people have you killed today?" chanted a crowd estimated by ACT UP at between 1,100 and 1,500 people. The protesters additionally hoisted a black banner that simply read "Federal Death Administration" as well as hoisted an effigy of then President Ronald Reagan.[14] The Atlantic later called it one of the most successful demonstrations during the time of the AIDS crisis.[15]

That same year, funding for national, regional, and community-based organizations to fight HIV/AIDS began. Comprehensive school-based education to begin teaching the young about the disease got started back in 1987.[16] Other changes due to activist pressure at the end of the 1980s were a reversal in the U.S. Department of Justice's decision making such that preventing discrimination against HIV patients became government policy plus a lowering of the price of AZT by 20%,[17][7] the drug being one of the first effective treatments against HIV but having prohibitively massive costs at first.[17] The former policy change became a matter of federal law in 1990 when President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

In terms of disease prevalence more generally, AIDS incidence increased rapidly through the 1980s only to peak in the early 1990s and subsequently decline into the dawn of the 21st century.[16] Activism meant by the early 1990s the FDA started a process known as "accelerated approval" that got experimental yet promising drugs to individuals with AIDS faster.[7]

In 2001, a CDC analysis of cases from 1981 through 2000 found that a full 774,467 persons had been reported with AIDS in the U.S. Of that total, 448,060 had died compared to 3542 persons with unknown vital status. The study's findings of 322,865 individuals living with AIDS were the highest ever reported.[16] UNAIDS data collected in 2007 stated that 0.6% of adults in the U.S. had HIV in comparison to 0.4% of Canadian adults.[4]

In terms of social change in the new tens, HIV/AIDS activists succeeded in pushing the Obama administration to issue an report finding that laws making HIV transmission a criminal offense do little to influence behavior while many "run counter to scientific evidence about routes of HIV transmission and effective measures of HIV prevention."[18] Activists additionally scored a major victory in October 2018 when California Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill into law that made knowingly exposing a sexual partner to HIV into a misdemeanor crime instead of a felony. WNYC labeled the change as "a legal and cultural milestone for the way Americans perceive HIV and AIDS."[19]

The activist organization Treatment Action Group (TAG) celebrated a victory in 2018 as well given that global spending on fighting tuberculosis hit a record high for 2017 compared to previous years. From 2016 to 2017, research spending jumped to $772 million from $726 million. TAG has spent years upon years pushing for better treatment of tuberculosis while taking careful note of the disease's status as a frequent problem for individuals with AIDS.[20]

History of anti-disease activism in Europe

Cases of mysterious deaths in Europe during the early 1980s caused the proliferation of discrimination, fear, and stigma like in other areas. The World Health Organization (WHO) has remarked in a statement that "AIDS was—and in absolute, global terms still is—a stinging challenge to the values of modernity received, for better or worse, from Europe's Age of Enlightenment... [since] [a]ffluent, confident, gender-progressive, often social-democratic welfare states awoke, in the early 1980s, to an uncomfortable reminder of their human frailty." On example of the extreme reactions by some politicians is far-right French figure Jean-Marie Le Pen and his proposal of confining people with HIV/AIDS in prison-like facilities.[21]

European politics have frequently involved championing the fight against HIV/AIDS as a human rights issue. Health care itself is also fundamentally seen as a matter of fundamental rights, requiring major government investment and regulation. Despite this, social changes have taken place since the world economic recession of the late 2000s that have shifted budgets' focus toward cost containment and increased efficiency.[21]

One of the world's most important anti-disease events got started in central Europe. Held yearly on 1 December, World AIDS Day was first conceived in August 1987 by James W. Bunn and Thomas Netter. The two public information officers worked for the Global Programme on AIDS at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland.[22]

Bunn later commented to NPR about his motivations at the time, stating that:

"The stigma that surrounded AIDS was actually twofold. One of it was what you could easily argue had to do with homophobia. But also there was a stigma of fear. There was a lot that people felt they did not know about the epidemic[,] and they were afraid. And they were right to be afraid because of the things that they were hearing... [while] the stigma that surrounded it made it something that people didn't want to talk about. If it came into their lives... also, for people who were affected by it, they did not want to bring up... their experience... with it because[,] in those days, people were being fired from their jobs. They were being denied Social Security benefits. They were being ostracized by their families. They were being evicted from their homes because they were sick and dying."[22]

History of anti-disease activism in South America

The regions of Latin America and the Caribbean contains a significantly large number of HIV cases. According to data from UNAIDS, this goes all the way up to two million people living with the disease. HIV/AIDS activism has taken place under the atmosphere of pervasive media bias against those diagnosed, particularly given the use of language such as "contagion" and "infection" in non-medical contexts.[23]

According to Luis E. Soto-Ramírez of Science:

There are issues in Latin America and the Caribbean that make epidemic conditions unique to the region. Many people still do not understand that HIV/AIDS is a viral, not a moral, infection. Widespread stigma and discrimination hamper efforts to achieve universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care. HIV transmission continues to occur among populations at higher risk, including sex workers, males that have sex with males (but increasing among heterosexuals), injecting drug users, and migrants. Prevention efforts, including education campaigns, are disorganized and poorly supported because budgets are mainly devoted to treatment.[24]

As with Africa, HIV prevalence differs notably from country to country inside Latin America and the Caribbean, although the values don't vary to the extent as in between African nations. For example, UNAIDS research in 2007 found that 3.0% of adults in the Bahamas had been inflected in comparison to the values of 1.1% in the Dominican Republic and 0.1% in Cuba.[4] When looking at new cases of infection, reporting presented at the International AIDS Conference held within Durban, South Africa in 2016 stated that only Chile and Uruguay managed to achieve a small reduction. Nations such as Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador among others had data showing worsening trends.[23]

Analysis of anti-disease activism

A 2018 report published by MD found that while efforts by ACT UP "arguably hastened the science, treatments and services for persons with HIV/AIDS", there still remained "found long-term effects on the activists" such as "concurrent posttraumatic stress responses and posttraumatic growth that are distinct from the experiences of persons affected by the illness but not involved with the campaign." However, the activists expressed gratitude for the opportunity to be a part of a close, positively-focused community.[25]

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) has stated as an organization that the "pressure of activists demanding early access to promising AIDS treatments" prompted fundamental changes within it. Activists managed to bust "the 'ivory tower' mentality wide open and forever" altered the specific paths "the search for treatments at NIH is conducted". The organization has credited the activists both with pushing to have drugs in the experimental stage more widely available for patients as well as more broadly having made stopping AIDS a systematic research priority.[26]

See also

References

- "The Treatment Action Campaign and the History of Rights-Based, Patient-Driven HIV/AIDS Activism in South Africa".

- Maggiano, Chris Cormier (8 September 2017). "Silence = Death". HuffPost. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- Alsop, Zoe (10 December 2009). "On Scene: With Uganda's Anti-Gay Movement". Time. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- A Global View of HIV Infection, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2008). Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Jaffe HW, Darrow WW, Echenberg DF, O'Malley PM, Getchell JP, Kalyanaraman VS, Byers RH, Drennan DP, Braff EH, Curran JW (1985). "The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in a cohort of homosexual men. A six-year follow-up study". Annals of Internal Medicine. 103 (2): 210–214. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-103-2-210. PMID 2990275.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control (June 1981). "Pneumocystis pneumonia – Los Angeles". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 30 (21): 250–2. PMID 6265753.

- "GMHC/HIV/AIDS Timeline". gmhc.org. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "In Their Own Words... 1981". history.nih.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "In Their Own Words... 1982". history.nih.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "NLM Launches 'Surviving and Thriving: AIDS, Politics, and Culture' – Traveling Banner Display and Online Exhibition". nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Sinclair, Mick (2004). San Francisco: A Cultural and Literary History. Signal Books. pp. 222–225. ISBN 9781902669656.

- Bernstein, Diana; Roaman, Chester A. (1988). "AIDS Awareness Week: An Operational Model". Journal of American College Health. 37 (1): 36–39. doi:10.1080/07448481.1988.9939039. PMID 3216084.

- "#9. AIDS Memorial Quilt". WTTW. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- International, United Press (11 October 1988). "Police Arrest AIDS Protesters Blocking Access to FDA Offices". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Crimp, Douglas (6 December 2011). "Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988". The Atlantic. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "HIV and AIDS --- United States, 1981—2000". MMWR Weekly. 1 June 2001 / 50(21); 430–434. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Hilts, Philip J.; Times, Special To the New York (19 September 1989). "Aids Drug's Maker Cuts Price by 20%". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2017/10/09/knowingly-infecting-others-with-hiv-is-no-longer-a-felony-in-california-advocates-say-it-targeted-sex-workers

- "Please Explain: HIV/AIDS Activism in the United States". WNYC. 30 March 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07708-z

- Smith, Julia (1 December 2016). "Europe's Shifting Response to HIV/AIDS". Health and Human Rights. 18 (2): 145–156. PMC 5395003. PMID 28559682.

- "NPR: How World AIDS Day Began". NPR. 1 December 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- Human Rights Campaign. "Stigma and Discrimination Around HIV and AIDS in Latin America". hrc.org. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- Soto-Ramírez, Luis E. (25 July 2008). "HIV/AIDS in Latin America". Science. 321 (5888): 465. doi:10.1126/science.1162896. PMID 18653849.

- Bender, Kenneth (4 June 2018). "How AIDS Activism Impacted Activists". MD. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- "In Their Own Words... Search for Treatments". history.nih.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2019.