HIV/AIDS in Haiti

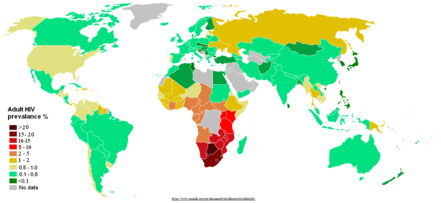

With an estimated 150,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in 2016 (or an approximately 2.1 percent prevalence rate among adults aged 15–49), Haiti has the most overall cases of HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean and its HIV prevalence rates among the highest percentage-wise in the region.[2] There are many risk factors groups for HIV infection in Haiti, with the most common ones including lower socioeconomic status, lower educational levels, risky behavior, and lower levels of awareness regarding HIV and its transmission.[3][4] However, HIV prevalence in Haiti is largely dropping as a result of a strong AIDS/HIV educational program, support from non-governmental organizations and private donors, as well as a strong healthcare system supported by UNAIDS. Part of the success of Haiti's HIV healthcare system lies in the governmental commitment to the issue, which alongside the support of donations from the Global Fund and President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), allows the nation to prioritize the issue.[1] Despite the extreme poverty afflicting a large Haitian population, the severe economic impact HIV has on the nation, and the controversy surrounding how the virus spread to Haiti and the United States, Haiti is on the path to provide universal treatment, with other developing nations emulating its AIDS treatment system.[1]

History

AIDS in Haitians was first recognized in 34 Haitians living in the United States in 1982, and in the same year eleven individuals in Haiti were suspected to be HIV infected.[1] Since the majority of these individuals did not fall into the classic risk factor groups, Haitians were classified as a separate risk factor group, causing damage to Haiti's image and economy and affecting tourism. In the same year, the Haitian Study Group on Kaposi's Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections (GHESKIO) was formed to study the new epidemic. GHESKIO used retrospective diagnosis to conclude that from 1979 to 1982, there were 61 cases of AIDS in Haiti. Through various studies and analyses, GHESKIO concluded that the risk factors identified in the 61 individuals were no different from those in other countries, with the primary risk factor being the fact that most of the patients lived in the suburb of Carrefour where prostitution was prevalent. The stigmatization of Haiti, however, continued, and during the presidency of Jean-Claude Duvalier, it was illegal to mention AIDS/HIV in Haiti.[5] From 1983 to 1987, the virus spread quickly through the population mostly through heterosexual sex, as HIV infected cases attributed to homosexuals or bisexuals went down from 50% to less than 1%.[1] In a 1985 to 2000 study, the virus spread twice as fast in developed nations prior to the use of antiretrovirals, as malnutrition, infectious communities, and active tuberculosis were all prevalent in Haiti.[1] Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the first democratically elected President of Haiti, was the first Haitian president to include HIV/AIDS into his platform for his 2001–2004 presidency and initiated governmental policies to ensure the blood supply remains uncontaminated and to prevent and treat the virus amongst the population.[6]

Prevalence

In Haiti, the three groups where HIV/AIDS is most prevalent are men who have sex with men, sex workers, and prisoners, with prevalence rates of 18.2, 8.4, and 4.3 respectively.[2] As opposed to the United States, intravenous drug use in Haiti was more rare and the blood supply was not initially affected by HIV infected individuals. As such, intravenous drug users and hemophiliacs were never major risk factor groups in Haiti since the start of the epidemic.[1]

As of 2017, UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, reports that HIV in Haiti is most prevalent among adults aged 15 to 49 and is primarily transmitted through heterosexual contact and mother-to-infant transmission.[7]

The recent declines in HIV infection rates are most notable in urban areas, and have been attributed to significant behavioral changes, including decreased number of partners, decreased sexual debut, and increased condom use. Other explanations for the recent trends include AIDS-related mortality and improvements made in blood safety early in the epidemic. However, continued political instability, high internal migration rates, high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections, and weakened health and social services persist as factors with potential negative impacts on the epidemic.[2]

Risk factors

According to a 2010 study, one major risk factor for HIV infection in Haiti, especially in women, is lower socioeconomic status.[3] In rural Haitian populations where education levels for women are low and many women are economically dependent on their husbands, a correlation between the stability of the occupation of the husband and HIV prevalence in the wives is observed.[3] Women whose husbands are market vendors or mechanics are at a higher risk of HIV infection. On the contrary, the wives of farmers, a more stable occupation, have a 60% lower risk of HIV infection.[3] Other indicators of low socioeconomic status, like the use of charcoal for cooking and food insecurity also show correlation with higher HIV infection rates in women.[3] The study stipulates that low socioeconomic status and high rates of HIV infection may be connected to the use of transactional sex as an economic survival strategy, a behavior shown in a related South African study to increase HIV infection rates by 1.5 times.[8] Similar trends from related studies have also been seen in other developing nations with gender disparities, such as Malawi, Rwanda, Kenya, Ghana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, and Uganda.[3]

Another vulnerable group is adolescents and young adults. For females, risk factor groups include those who have low levels of education, live away from their parents, have been married, or have had a child.[4] For males, factors indicative of HIV infection are intravenous drug use and sexual debut with an unknown individual.[4] For both genders, young adults who are less aware of HIV and its transmission through risky behavior are more likely to be infected, and amongst females, those who talked more openly about HIV infection and testing were less likely to be infected.[4] Finally, having sexual contact with unfaithful partners, having an STI, especially syphilis, and not using condoms are all additional risk factors that affect both genders.[4]

Economic impact

On the national level, HIV causes damage to the Haitian economy because the individuals most affected by the epidemic are the young adults that contribute the most to the country's economy.[9] At the start of the epidemic, Haiti's tourism and export industries suffered when Haitians were classified as an HIV risk group.[10] According to Jean Pape, the head of the largest Haitian HIV research center, Haitian products could no longer be sold in the US and tourism, which was the basis of the Haitian economy, declined drastically.[10] With 54% of the Haiti economy based on the service and tourism sector, HIV further weakened Haiti's already struggling economy.[5]

On a household level, HIV causes significant economic strain to the family of infected individuals.[11] HIV infection in a parent can lead to the loss of one source of income which in turn leads to malnutrition, lack of access to education for the children, and increased risk of child labor.[9] The cost of healthcare is another burden on the family.[11] From a 1997 study involving 600 households from Côte d'Ivoire, Burundi, and Haiti, households with at least one HIV infected family member spent nearly twice the amount on healthcare (around 10.6%) compared to families without HIV infected individuals, decreasing household consumption in other areas.[11] The HIV treatment also on average took up 80% of the entire family's healthcare budget. Even after the death of the HIV infected individual, the household never completely returned to its original level of consumption.[11]

HIV treatment and prevention

Nearly 75% of HIV treatment in Haiti is sponsored and overseen by the NGOs Partners In Health and Haitian Study Group on Kaposi's Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections (GHESKIO) in collaboration with the Haitian Ministry of Health.[1] Alongside them, the Joint United Nations Team on AIDS (Joint Team) in Haiti also helps provide the resources to tackle HIV through prevention, treatment, and testing, accelerating the nationwide HIV response.[2] As of 2016, around 55% of HIV positive Haitians received antiretroviral therapy.[2]

Elimination of mother to child transmission

Prior to the efforts to eliminate vertical transmission of HIV, around 27% of babies born to HIV infected mothers in Haiti contracted the virus from their mothers through breast milk.[1] As a preventative measure, GHESKIO and the Ministry of Health set up national guidelines for HIV infected mothers and newborn babies to receive doses of zidovudine. Since 2003, Haiti has altered its guidelines to allow triple drug ART for pregnant HIV infected women, treatments for existing opportunistic infections, and counseling on the use of formula feed instead of breast milk to lower transmission rates.[1] Since the use of triple therapy, HIV transmission rates from mother to child for those on triple drug ART has decreased to around 1.9%, while the transmission rates among all pregnant women treated for HIV in any form has dropped to 9.2%, both of which are significant decreases from the initial 27% vertical transmission.[1] The Joint Team and UNICEF also provides manuals on preventing mother to child transmission of HIV and offers prenatal and postpartum counseling services to HIV infected mothers to stem vertical transmission in Haiti.[2] However, further educational efforts are necessary as only around 40% of Haitian HIV infected mothers attend these counseling services, and an even smaller amount get tested for HIV prior to childbirth.[1] Around 80% of Haitians recognize that the virus can be transmitted vertically, however, the majority of Haitians do not know that treatment of both the mother and child in the weeks before and after childbirth can greatly decrease the risk of infection in the baby.[1] This coupled with the fact that around 80% of childbirth in Haiti takes place at home instead of in a hospital necessitates that further connection of HIV infected individuals with the health networks in Haiti is essential to stem vertical transmission.[1]

HIV Equity Initiative

In 1985, Paul Farmer and his colleagues created a clinic in the Central Plateau of Haiti to serve those displaced by the creation of a hydroelectric dam. The first case of HIV recorded at this clinic was in 1986. In 1987, Farmer spearheaded the effort that lead to the founding of Partners in Health. After a 1994 paper detailing the effects of AZT on lowering the rates of transmission from mother to child, the HIV clinic began offering HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy to pregnant mothers, leading to a sharp decline of cases of mother to child transmission.[12] Starting in 1997, the clinic made post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) available to women who suffered from rape and HIV health workers who had occupation injuries. In late 1998, individuals with long term severe opportunistic infections were offered antiretroviral therapy as opposed to only being allowed to treat their symptoms for free. For those infected with the more life-threatening tuberculosis, anti-tuberculous therapy was prioritized over ART.[12] Partners in Health's success largely comes from the directly observed therapy that is given to the patients, through health care workers known as accompagnateurs.[12] Accompagnateurs help the therapy process by making sure the pills are taken on time, answering questions and concerns, and offering moral support to patients and their families. The clinic also assists the family by offering social services such as payment of tuition and highly attended meetings for patients to stay involved in the treatment process.[12] The success of the program in Haiti served as a model to other developing nations that, despite high unemployment, low GDP per capita, and high HIV prevalence, a nation can have a successful HIV treatment program, regardless of urbanization and wealth.[12]

HIV prevention

HIV prevention has been brought about, especially in the younger generation, through education and the spreading of awareness of safe sex practices and condom use.[1] The Joint Team, in 2016, has collaborated with the Ministry of Education to create health clubs and programs in 100 schools as well as trained 566 educators, supplied over a million condoms, hosted more than 7000 HIV tests, and referred more than 80% of infected individuals from those tests to seek treatment.[2] UNICEF also sponsored efforts to create a video series and a Facebook page targeted towards the 15–35 age group to spread awareness about the risks of HIV and measures to prevent transmission.[2]

Challenges

After the devastation caused by the 2010 Haitian Earthquake, Haiti's HIV treatment system was affected greatly. Estimates by the Haitian government indicate that around 40% of the initial 24,000 Haitians lost access to antiretrovirals after the earthquake.[13] HIV positive individuals displaced due to the earthquake often live in substandard conditions in tent cities, decreasing their immunity and increasing their susceptibility to infection or progressing to AIDS. The large concentration of HIV positive individuals in confined tent cities also increases the risk of HIV transmission within the smaller community of individuals.[13] However, the overall structure of the HIV treatment system has largely remained intact and the majority of HIV infected patients continue to receive access to antiviral therapy while the nation rebuilds the rest of its healthcare system.[1]

Other challenges to the HIV treatment and prevention efforts in Haiti include more recent events, such as Hurricane Matthew, the cholera outbreak, and additional refugees arriving from the Dominican Republic, the limitations on the human and financial resources the NGOs can provide, and the fluctuating level of cooperation from the Haitian government.[2]

The Haitian connection controversy

The Haitian connection controversy refers to the debate regarding the origins of the HIV virus in Haiti and the United States and whether or not HIV was spread into the US by Haitians or into Haiti by Americans. The controversy began in the 1982, when the CDC noted that 34 cases of immunodeficient patients were Haitian.[1] This "connection" noted by physicians caused the erroneous labeling of Haitians as a risk factor group for HIV, leading to the rise of the term "the 4-H's" referring to Homosexuals, Hemophiliacs, Heroin addicts, and Haitians as the major groups prone to HIV infection.[14]

Dr. Jacques Pépin, a Quebecer author of The Origins of AIDS, stipulated that Haiti was one of HIV's entry points to the United States. In July 1960, when Belgian Congo gained independence, the United Nations recruited Francophone experts and technicians from all over the world to assist in filling administrative gaps left by Belgium.[15] By 1962, Haitians made up the second largest group of well-educated experts in the country totaling around 4500. One of them may have carried HIV back across the Atlantic in the 1960s. Pépin argues that its spread in Haiti was sped by poor Haitians in need of money selling their blood plasma at centers such as Hemo-Caribbean, which was known to have poor hygienic practices.[15] Plasma centers separated plasma from blood cells and failed to change needles and tubing between patients, a practice that rapidly spreads blood-borne diseases. Luckner Cambronne, co-owner of Hemo-Caribbean and known as the "Vampire of the Caribbean", was notorious for selling Haitian blood and cadavers abroad for medical uses. Plasma from Hemo-Caribbean was exported to the United States at a maximum rate of 5,000 to 6,000 litres per month in the early 1970s.[15]

In his 1990 book "AIDS and Accusation," Paul Farmer refutes the idea that Haiti was an HIV entry point to the USA. Referencing an epidemiological study on the prevalence of sarcomas associated with HIV/AIDS contraction, Farmer suggests that Cambronne's plasma business occurred before identifiers of HIV infection were recorded in Haiti, indicating that the disease did not arrive in Haiti until at least the late-1970s.[16] Farmer instead argues that HIV/AIDS in Haiti was introduced by visitors from the US.[16]

In a 2007 study, 5 HIV isolates from different regions were compared on the molecular level. By comparing the number of mutations present in different strands of HIV found from patients from Central Africa, the United States, and Haiti, the results predict that the Haitian strain of the virus is the genetic midpoint between the strains found in Central Africa and the United States, and that the virus traveled from Haiti to the United States about 3 years after it reached Haiti.[17] However, this study is refuted by Jean Pape as a continuation of decades old prejudice against Haiti in regards to the AIDS epidemic, as the study does not provide conclusive evidence that the virus traveled from Haiti to the US.[17]

Regardless of origin, the consequences of HIV/AIDS in Haiti were severe. The disease spread rapidly throughout Haiti, infecting thousands.[1] Haiti's burgeoning tourist industry suffered greatly from the association with HIV/AIDS, and Haitians living in the USA were placed on the banned list for blood donations, alongside homosexuals and intravenous drug users, until 1990.[18]

See also

References

- Koenig, Serena; Ivers, Lc; Pace, S; Destine, R; Leandre, F; Grandpierre, R; Mukherjee, J; Farmer, Pe; Pape, Jw (2010-03-01). "Successes and challenges of HIV treatment programs in Haiti: aftermath of the earthquake". HIV Therapy. 4 (2): 145–160. doi:10.2217/hiv.10.6. ISSN 1758-4310. PMC 3011860. PMID 21197385.

- "Haiti". www.unaids.org. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- Fawzi, M.C. Smith; Lambert, W.; Boehm, F.; Finkelstein, J.l.; Singler, J.m.; Léandre, F.; Nevil, P.; Bertrand, D.; Claude, M.s. (2010-04-10). "Economic Risk Factors for HIV Infection Among Women in Rural Haiti: Implications for HIV Prevention Policies and Programs in Resource-Poor Settings". Journal of Women's Health. 19 (5): 885–892. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1334. ISSN 1540-9996. PMC 2875958. PMID 20380576.

- Dorjgochoo, Tsogzolmaa; Noel, Francine; Deschamps, Marie Marcelle; Theodore, Harry; Dupont, William; Wright, Peter F; Fitzgerald, Dan W; Vermund, Sten H; Pape, Jean W (2009). "Risk Factors for HIV Infection Among Haitian Adolescents and Young Adults Seeking Counseling and Testing in Port-au-Prince". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 52 (4): 498–508. doi:10.1097/qai.0b013e3181ac12a8. PMC 3196358. PMID 19738486.

- "The Sleeping Catastrophe: HIV/AIDS in an Already Devastated Haiti". Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- Hempstone, Hope (2004). "HIV/AIDS in Haiti: A Literature Review" (PDF).

- "Caribbean HIV & AIDS Statistics".

- Dunkle, Kristin L.; Jewkes, Rachel K.; Brown, Heather C.; Gray, Glenda E.; McIntryre, James A.; Harlow, Sioḃán D. (2004). "Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection". Social Science & Medicine. 59 (8): 1581–1592. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003. PMID 15279917.

- Georges, Yves Marie Dominique (2011). HIV/AIDS in Haiti. An Analysis of Demographics, Lifestyle, STD Awareness, HIV Knowledge and Perception that Influence HIV Infection among Haitians (Thesis). Georgia State University.

- "HIV/AIDS in Haiti and Latin America – The Globalist". The Globalist. 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "The Impact of AIDS". www.un.org. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- Farmer, P.; Léandre, F.; Mukherjee, J. S.; Claude, M.; Nevil, P.; Smith-Fawzi, M. C.; Koenig, S. P.; Castro, A.; Becerra, M. C. (2001-08-04). "Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings". Lancet. 358 (9279): 404–409. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05550-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11502340.

- "After the Quake: HIV/AIDS in Haiti". Pulitzer Center. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- "Origin of HIV & AIDS". AVERT. 2015-07-20. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- Pépin, Jacques, ed. (2011-09-01). The Origin of Aids. Cambridge University Press. p. 188; 201. ISBN 9781139501415. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- 1959–, Farmer, Paul (2006). AIDS and accusation : Haiti and the geography of blame (Updated with a new preface ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520248397. OCLC 62738653.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Cohen, Jon (2007-11-02). "Reconstructing the Origins of the AIDS Epidemic From Archived HIV Isolates". Science. 318 (5851): 731. doi:10.1126/science.318.5851.731a. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17975041.

- Hilts, Philip J.; Times, Special to The New York (1990-04-24). "F.D.A. Set To Reverse Blood Ban". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-12-01.